Cries in the Night, more popularly released as Funeral Home,[3] is a 1980 Canadian slasher film directed by William Fruet and starring Lesleh Donaldson, Kay Hawtrey, Jack Van Evera, Alf Humphreys, and Harvey Atkin. The plot follows a teenager spending the summer at her grandmother's inn—formerly a funeral home—where guests begin to disappear.

| Funeral Home | |

|---|---|

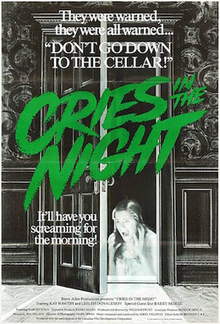

Original theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | William Fruet |

| Screenplay by | Ida Nelson |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Mark Irwin |

| Edited by | Ralph Brunjes |

| Music by | Jerry Fielding |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.3 million[2] |

Briefly released in eastern Canada in 1980, the film premiered in the United States and was re-released in its native Canada under the alternative title Funeral Home in the summer of 1982. It received mixed reviews from critics, with several noting it as starkly redolent of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960).[4][5]

Plot

editAt the beginning of the summer, Heather arrives in a small unnamed town to stay with her eccentric and religious grandmother, Maude Chalmers, whose house—a former funeral home—has recently been converted into an inn. Maude's husband, James, an undertaker, has been missing for several years, and she has been forced to make a living selling artificial flower arrangements; she hopes to supplant her income by opening the home to traveling guests. Billy Hibbs, a mentally-challenged man, lives with Maude as the property handyman.

Nearby, a farmer named Sam reports an abandoned vehicle discovered on his property, which is traced to a missing real estate developer who had been surveying the area. At the inn on the evening of Heather's arrival, guests Harry Browning and his mistress Florie check in. When Maude realizes the couple are unmarried, she asks them to leave, but they refuse. That evening after having drinks, they drive to a local quarry recommended by Heather; while there, Maude's truck arrives, smashing the back of their car and pushing them into the water below, where they both drown. The same night, Heather goes on a date with Rick, a local teenager, and returns home to hear her Maude speaking to an unseen man in the basement. When she inquires, Maude denies it.

The next day, while Maude is in town, Rick stops by the house. He tells Heather that her grandfather, James, was a known alcoholic, and recounts a story from his childhood in which Mr. Chalmers had locked him and a friend in the funeral home's basement to scare them. The two explore the property while Maude is gone; in the garage, they discover Mr. Chalmer's Cadillac hearse, and Heather finds a necklace with the initials "H.D." engraved on it. That evening, Heather again hears Maude speaking to someone in the basement, this time arguing with a male voice about a woman named "Helena Davis." Heather discovers Helena has been missing for some time, and was rumored to have eloped with her grandfather. Mr. Davis, Helena's husband, arrives at the house to ask Maude about the alleged affair, which she denies ever occurred. Later that evening, Mr. Davis is murdered with a pickaxe.

The following day while Heather and Rick are swimming in the quarry, Florie and Harry's bodies are discovered. Heather confides in Rick that she believes her grandmother is hiding someone in the basement. That evening, they return to the house. Upon finding that Maude is not home, the two decide to explore the basement. There they discover Billy's corpse, and are attacked by Maude, who, imitating her husband's voice, scolds Heather for coming into the basement. Maude attempts to kill Heather with an axe and she flees through the basement, discovering a hidden room where James's corpse rests in a bed of Maude's artificial flowers. Just as Maude is about to strike Heather with the axe, she lapses out of her dissociative identity. The police arrive at the scene in the basement, and Joe, a local police officer, asks Maude if they can talk about what has occurred. She agrees, so long as she can prepare a cup of tea.

Later, Joe explains to a news reporter that Maude had murdered James and Helena, his mistress, after discovering their affair. After, she preserved James's corpse, and buried both Helena and Mr. Davis in the local graveyard.

Cast

edit- Kay Hawtrey as Maude Chalmers

- Lesleh Donaldson as Heather

- Barry Morse as Mr. Davis

- Dean Garbett as Rick Yates

- Stephen E. Miller as Billy Hibbs

- Alf Humphreys as Joe Yates

- Peggy Mahon as Florie

- Harvey Atkin as Harry Browning

- Robert Warner as Sheriff

- Jack Van Evera as James Chalmers

- Les Rubie as Sam

- Doris Petrie as Ruby

- Bill Lake as Frank

- Brett Matthew Davidson as Young Rick

- Christopher Crabb as Teddy

- Robert Craig as Barry Oaks

- Linda Dalby as Linda

- Gerard Jordan as Pete

- Eleanor Beecroft as Shirley

Production

editFilming

editThe budget for the film was roughly CAD$1,431,780 and the production was filmed from July 23, 1979 to September 12, 1979. It as shot on location in several cities in Ontario, including Elora, Guelph, Markham, and Toronto.[6] The building that stood in for the Chalmers Funeral Home was in actuality not a funeral home; it was a spacious mansion with gables located on Reesor Road in Markham, Ontario, and this house was later used again in an episode of the 1990s Canadian-American horror anthology series Goosebumps (as the O'Dell House in the 2-part episode "Night of the Living Dummy III"), which Fruet co-produced. The scenes at the quarry were filmed at the Elora Quarry in Elora, Ontario; this quarry has been a conservation park and public beach since the 1970s, and unlike the Reesor mansion, can be visited by tourists. Both locations were sought out and booked for filming in advance by Fruet.[7][8]

According to actress Lesleh Donaldson, actress Kay Hawtrey and director William Fruet did not get along well, stating that "She couldn’t stand him. She hated him. Just hated him." She also recalled Hawtrey "...being a nervous wreck nearly every morning. And then she claimed Bill was making her do stuff at the end that was too much for her. In the scene where she's down in the cellar, there were a lot of crew guys doubling for her, with the axe and swinging stuff around. It wasn’t her doing that."[9]

On director Fruet, Donaldson stated that she "knew that he would do things off-the-cuff at the last minute, like changing a scene. [I] might not have been called in that day and suddenly I’d get a call telling me "Get to the set now!", and I’d have to do a scene I hadn’t memorized yet. It was tense that way."[9]

Release

editBox office

editThe film was first released in eastern Canada[4] through Frontier Amusements, opening in Kitchener, Ontario on October 3, 1980.[1] It later opened in Brantford, Ontario on April 24, 1981.[10] The following summer, Motion Picture Marketing re-released it under the alternative title Funeral Home in various cities in the United States, including Salt Lake City,[11] Philadelphia,[12] and Kansas City, Missouri.[13] It was also re-released in its native Canada under this revised title: It screened as Funeral Home in Calgary in July 1982,[14] and in Vancouver in August 1982.[4] The film premiered in Los Angeles on January 28, 1983.[15]

Between its releases in Canada and the United States, the film grossed $1,301,700 at the box office.[2]

Critical response

editMichael Walsh of The Province praised the film for its moody cinematography but felt the screenplay was too derivative of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960), summarizing: "Burdened with a bland, obvious script and unwilling to indulge itself in truly explicit violence, [It] is neither mysterious nor particularly shocking. It ends up being a mild-mannered Psycho clone."[4] Robert C. Trussell of The Kansas City Star gave the film an unfavorable review, remarking that it contained uninspired dialogue and poor character development, ultimately deeming it "so boring it could be recommended for heart patients."[13] Allan Ulrich of the San Francisco Examiner also described the film as lacking in suspense and excitement, writing that the plotting was "predictable, the denouement tiresome, the violence perfunctory."[16]

Alternately, Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times praised the film for its empathetic character portrayals and "realistic Canadian style," as well as for Hawtrey's performance and the "capable supporting cast."[17]

The film has received mixed to positive reception in recent years, with AllMovie, in their summary of the film, stating that "...Funeral Home serves up a generous supply of shudders even for non-fans of the horror genre." In a retrospective analysis, critic and film historian John Kenneth Muir said the film is "slow as molasses and lacking in both surprises and punch," and negatively compared it to imitating Hitchcock's Psycho (1960).[5]

Thomas Ellison of Retro Slashers.net gave the film a positive review, stating that "Funeral Home is the type of slasher that relies on story and actor performances...Fruet takes a much more atmospheric route." However that the ending "...borrows too heavily from another slasher film."[18]

Accolades

editCries in the Night was nominated for three Genie Awards:[19][20]

- Best Actress: Lesleh Donaldson

- Best Editing: Ralph Brunjes

- Best Sound Editing: Andy Herman, Dave Appleby, Joe Grimaldi, Gary Bourgeois, Austin Grimaldi, and Ian Hendry

Home media

editThe film was released on VHS by Vouge Video in Canada in 1982[5] and Paragon Video[21] in 1983 and again in 1986 as a big box reissue.[22] It was officially released on DVD by Mill Creek Entertainment in 2005; however, this release was sourced from a low-quality VHS transfer.[23]

On February 6, 2024, Scream Factory released the film for the first time in high-definition on Blu-ray.[24][25]

Soundtrack

editA soundtrack to the film was released on October 25, 2011 by Intrada Records as part of their Intrada Special Collection Series.[26]

All tracks were composed by Jerry Fielding. The film was his second-to last score.[27]

- Main Title [2:50]

- The Cat [0:54]

- Heather's Arrival [1:05]

- Home Sweet Home [1:10]

- Whispering Corridors [2:20]

- You Like the Way I Look [3:34]

- Going, Going, Gone [2:15]

- Mysteries of the Dark [0:37]

- Animal Magnetism [2:33]

- Garage Discovery [0:42]

- The Lure [1:21]

- Home, Not So Sweet Home [2:24]

- Voices in the Basement [4:52]

- Vicious Gossip [1:57]

- Davis Whacked [3:44]

- Water Rescue [1:00]

- Billy's Demise [4:46]

- Coffin Ready [2:04]

- Grandma Unhinged [2:20]

- Meet Mr. Chalmers [1:01]

- Finish [2:46]

- Not Quite Country [3:30]

- Just the Old Car Radio [2:05]

- Brass Ensemble [1:10]

- Rock of Ages/Brass [2:11]

- Rock of Ages/Organ [2:00]

- Wild Pump Organ [1:28]

- Rock of Ages/Pump Organ [1:18]

See also

edit- Hotel Infierno - A 2015 Argentine film with a similar plot

References

edit- ^ a b "Starts Tonight in 4 Theatres: Cries in the Night". Waterloo Region Record. October 3, 1980. p. 37 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Donahue 1987, p. 297.

- ^ Pratley 2003, p. 255.

- ^ a b c d Walsh, Michael (August 30, 1982). "Funeral Home a weak, mild Psycho clone". The Province. p. A7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Muir 2012, p. 241.

- ^ Gagne, Andre (October 22, 2016). "The Great Red North: Canuck Horror Cinema". Ottawa Life Magazine. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023.

- ^ "Abandoned quarry is an epic swimming hole one hour from Toronto". www.blogto.com. BlogTO. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "7960 Reesor Rd". SkyHub. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Losing Her Head: An Interview with Lesleh Donaldson". The Terror Trap. November 2011. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012.

- ^ "Cries in the Night: Starts Today!". The Expositor. April 24, 1981. p. 24 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Funeral Home: Now Showing". The Salt Lake Tribune. June 4, 1982. p. 64 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "2 Shiver-and-Shudder Spine Tinglers". The Philadelphia Inquirer. July 2, 1982. p. 75 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Trussell, Robert C. (August 29, 1982). "'Funeral Home' can bore you to death". The Kansas City Star. p. 32A – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Funeral Home". Calgary Herald. July 23, 1982. p. 38 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Funeral Home: Starts Today". Los Angeles Times. January 28, 1983. p. VI-16 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ulrich, Allan (September 21, 1982). "'Funeral Home' a frightful film". San Francisco Examiner. p. E5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (February 1, 1983). "'Funeral Home' Serves Empathy with Horror". Los Angeles Times. pp. VI-1, VI-5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ellison, Thomas (January 16, 2008). "Funeral Home (1981) Review". Retro Slashers. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Jay (February 4, 1982). "Academy lists Genie nominees". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Here are the award contenders". The Province. February 4, 1982. p. 27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Burkart, Gregory (May 24, 2016). "Slashback! "Chalmers the Embalmers" Run a B&B to Die For in 1980's FUNERAL HOME". Blumhouse Productions. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016.

- ^ Weldon 1996, p. 224.

- ^ H., Brett (March 23, 2008). "Horror Reviews - Funeral Home (1980)". Oh, the Horror!. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ "Funeral Home [Special Edition]". Shout! Factory. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024.

- ^ Landy, Tom (January 18, 2024). "Scream Factory Digs Up Funeral Home for a Special Edition Blu-ray on February 6th". High-Def Digest. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Funeral Home Soundtrack (1980)". Movie Music Store. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Hischak 2015, p. 236.

Sources

edit- Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American Film Distribution: The Changing Marketplace. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. ISBN 978-0-835-71776-2.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2015). The Encyclopedia of Film Composers. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-442-24549-5.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2012). Horror Films of the 1980s. Vol. 1. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-47298-7.

- Pratley, Gerald (2003). A Century of Canadian Cinema: Gerald Pratley's Feature Film Guide, 1900 to the Present. Lynx Images. ISBN 978-1-894-07321-9.

- Weldon, Michael J. (1996). The Psychotronic Video Guide To Film. New York City, New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-13149-4.