Codex Dublinensis is a Greek uncial manuscript of the New Testament Gospels, written on parchment. It is designated by Z or 035 in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts, and ε 26 in the von Soden numbering of New Testament manuscripts. Using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), it has been dated to the 6th century CE.[1] The manuscript has several gaps.[2]

| New Testament manuscript | |

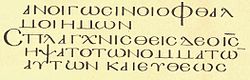

Matthew 20:33-34 | |

| Name | Dublinensis |

|---|---|

| Sign | Z |

| Text | Gospel of Matthew |

| Date | 6th century |

| Script | Greek |

| Found | Barrett 1787 |

| Now at | Trinity College Library, Dublin |

| Size | 27 cm by 20 cm |

| Type | Alexandrian text-type |

| Category | III |

It is a palimpsest manuscript, the upper layer containing excerpts from commentaries by early Church fathers.

Description

editThe manuscript is a codex (precursor to the modern book), containing a portions of the text of Gospel of Matthew on 32 parchment leaves (sixed 27 cm by 20 cm), with numerous gaps. The manuscript itself is a palimpsest (a manuscript with the initial text washed off, and then written over again with a different text), currently consisting of 110 folios from a likely total of 120, with 69 of these being palimpsest.[3]: 4 The upper text is a patristic commentary written in a minuscule hand, with most of the commentary from the works of John Chrysostom. Other present comments are from the writings of Basil, Anastasius, Epiphanius, and Theodorus Abucara.[3]: 3 The upper text is written with "no elegance" or "magnificence", and is much mutilated.[3]: 4 The under-text is written in one column per page, 21 lines per column, with 27 letters per line.[2] The original parchment was purplish in colour, rather thin, and the writing on one side shows through to the other in many places, and there are many holes present.[3]: 4 The manuscript has been rebound at some point between 1801 and 1853, to which biblical scholar Samuel Tregelles decries:

The binder simply seems to have known of the Greek book in the cursive letters, which are all black and plain to the eye. And so the pages have been unmercifully strengthened in parts, by pasting paper or vellum over the margins, leaving indeed the cursive writing untouched, but burying the uncial letters, of so much greater value... Also in places there were fragments all rough at the edges of the leaves, and these have been cut away so as to make all smooth and neat ; and thus many words and parts of words read by Dr. Barrett are now gone irrecoverably.[3]: 5-6

According to biblical scholar Bruce Metzger, the uncial letters are large and broad,[4] and biblical scholar T. K Abbott describes the letters as "beautifully formed."[3]: 6 The letters are larger than in codices Alexandrinus and Vaticanus, but smaller than in Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus.[5] Itacistic errors are present, e.g. αι confused with ε, and ι with ει.[5] The letters have no breathings or accents, and the Old Testament quotations are indicated by a diplai (>).[3]: 6 The letter μ (mu) is very peculiar, looking more like an inverted Π (pi). The codex contains the Ammonian Sections, but there is no Eusebian Canons.[6][3]: 8 The conventional nomina sacra are present, with several sometimes being written out in full (μητηρ / mother, ουρανος / heaven/sky, ανθρωπος / man/human, and υιος / son).[3]: 8

- Contents

Matthew 1:17-2:6, 2:13-20, 4:4-13, 5:45-6:15, 7:16-8:6, 10:40-11:18, 12:43-13:11, 13:57-14:19, 15:13-23, 17:9-17, 17:26-18:6, 19:4-12, 21-28, 20:7-21:8, 21:23-30, 22:16-25, 22:37-23:3, 23:15-23, 24:15-25, 25:1-11, 26:21-29, 62-71.[7]

Text

editThe Greek text of this codex is considered a representative of the Alexandrian text-type, with many alien readings. The Alexandrian text is similiar to that seen in Codex Sinaiticus.[4] Textual critic and biblical scholar Kurt Aland placed it in Category III of his New Testment manuscript classification system.[2] Category III manuscripts are described as having "a small but not a negligible proportion of early readings, with a considerable encroachment of [Byzantine] readings, and significant readings from other sources as yet unidentified."[2]: 335

The Lord's Prayer (Matthew 6:13) does not contain the usual doxology: οτι σου εστιν η βασιλεια και η δυναμις και η δοξα εις τους αιωνας (because the kingdom and the power and the glory is yours, forever) as in codices א B D 0170 ƒ1.[8]: 13

In Matthew 20:23 it does not contain και το βαπτισμα ο εγω βαπτιζομαι βαπτισθησεσθε (and be baptized with the baptism that I am baptized with), as in codices א B D L Θ 085 ƒ1 ƒ13 it syrs, c sa.[9]: 56

History

editThe history of the codex is unknown until the underlying text was discovered by John Barrett in 1787, under some cursive writing. Barrett published its text in 1801,[3]: 3 but with errors. The codex was exposed to chemicals by Tregelles, and was deciphered by him in 1853.[10] Tregelles added about 200 letters to the text of Barrett. A further edition was published by T. K. Abbott in 1880.[4][3]

The codex is currently located in the Trinity College Library (shelf number K 3.4) in Dublin, Ireland.[2][11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Andrews, Edward D.; Wilkins, Don (2017). The Text of the New Testament: The Science and Art of Textual Criticism. Cambridge, OH: Christian Publishing House. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-945757-44-0.

- ^ a b c d e Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Abbott, Thomas Kingsmill (1880). Par palimsestorum Dublinensium: The codex rescriptus Dublinensis of St. Matthew's gospel (Z) - A New Edition Revised and Augmented. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- ^ a b c Metzger, Bruce Manning; Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-19-516667-1.

- ^ a b Gregory, Caspar René (1900). Textkritik des Neuen Testamentes. Vol. 1. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. pp. 83–85.

- ^ Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. Vol. 1 (4 ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. pp. 153–155.

- ^ Aland, Kurt (1996). Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum. Locis parallelis evangeliorum apocryphorum et patrum adhibitis edidit (in German). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. p. XXIV.

- ^ Aland, Kurt; Black, Matthew; Martini, Carlo Maria; Metzger, Bruce Manning; Wikgren, Allen, eds. (1983). The Greek New Testament (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: United Bible Societies. ISBN 9783438051103. (UBS3)

- ^ Aland, Kurt; Black, Matthew; Martini, Carlo Maria; Metzger, Bruce M.; Wikgren, Allen, eds. (1981). Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece (26 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung. ISBN 3-438-051001. (NA26)

- ^ S. P. Tregelles, An Account of the Printed Text of the Greek New Testament, London 1854, pp. 166-169.

- ^ "Liste Handschriften". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

Further reading

edit- John Barrett, Evangelium secundum Matthaeum ex codice rescripto in bibliotheca collegii ssae Trinitatis iuxta Dublinum (Dublin, 1801).

- S. P. Tregelles, The Dublin codex rescriptus: a supplement (London, 1863).

- T. K. Abbott, On An Uncial Palimpsest Evangelistarium, Hermathena X (1884), pp. 146–150.

- J. G. Smyly, Notes on Greek Mss. in the Library of Trinity College, Hermathena XLVIII (1933).

External links

edit- Codex Dublinensis Z (035): at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism