Chamar (or Jatav)[2] is a Dalit community classified as a Scheduled Caste under modern India's system of affirmative action. They are found throughout the Indian subcontinent, mainly in the northern states of India and in Pakistan and Nepal.

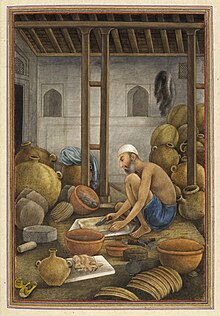

Leather-bottle makers (Presumably members of the 'Chamaar' caste), Tashrih al-aqvam (1825) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India • Pakistan | |

| Languages | |

| Hindi • Punjabi | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism • Islam • Sikhism • Ravidassia religion • Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Jatav • Chanwar Chamar • Ramdasia • Ravidassia • Raigar[1] • Chambar • Dhusia • Julaha Chamar • Kabirpanthi Julaha • Ahirwar |

History

The Chamars are traditionally associated with leather work.[3] Ramnarayan Rawat posits that the association of the Chamar community with a traditional occupation of tanning was constructed, and that the Chamars were instead historically agriculturists.[4]

The term chamar is used as a pejorative word for dalits in general.[5][6] It has been described as a casteist slur by the Supreme Court of India and the use of the term to address a person as a violation of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.[7]

In reference to villages of Rohtas and Bhojpur district of Bihar, prevalence of a practice was revealed, in which it was obligatory for the women of Chamar, Musahar and Dusadh community to have sexual contacts with their Rajput landlords. In order to keep their men in submissive position, these upper-caste landlords raped these Dalit women, and often implicate the male members of latter's family in false cases, when they refused sexual contacts with them. The other form of oppression which was inflicted on them was disallowing them to walk on the pathways and draw water from the wells, which belonged to Rajputs. The "pinching of breast" by the upper caste landlords and the undignified teasings were also common form of oppression. In the 1970s, the activism of peasant organizations like "Kisan Samiti" is said to have brought an end to these practices and subsequently the dignity was restored to the women of lower castes. The oppression however was not fully stopped as the friction between upper-caste landlords and the tillers continued. There are reports which indicates that the upper-caste landlords often took the help of Police in order to beat the women of Chamar caste and draw them out of their villages on the question of parity in wages.[8][9][10]

Movement for upward social mobility

Between the 1830s and the 1950s, the Chamars in the United Provinces, especially in the Kanpur area, became prosperous as a result of their involvement in the British leather trade.[11]

By the late 19th century, the Chamars began rewriting their caste histories, claiming Kshatriya descent.[12] For example, around 1910, U.B.S. Raghuvanshi published Shri Chanvar Purana from Kanpur, claiming that the Chamars were originally a community of Kshatriya rulers. He claimed to have obtained this information from Chanvar Purana, an ancient Sanskrit-language text purportedly discovered by a sage in a Himalayan cave. According to Raghuvanshi's narrative, the god Vishnu once appeared in form of a Shudra before the community's ancient king Chamunda Rai. The king chastised Vishnu for reciting the Vedas, an act forbidden for a Shudra. The god then revealed his true self, and cursed his lineage to become Chamars, who would be lower in status than the Shudras. When the king apologized, the god declared that the Chamars will get an opportunity to rise again in the Kaliyuga after the appearance of a new sage (whom Raghuvanshi identifies as Ravidas).[13]

A section of Chamars claimed Kshatriya status as Jatavs, tracing their lineage to Krishna, and thus, associating them with the Yadavs. Jatav Veer Mahasabha, an association of Jatav men founded in 1917, published multiple pamphlets making such claims in the first half of the 20th century.[14] The association discriminated against lower-status Chamars, such as the "Guliyas", who did not claim Kshatriya status.[15]

In the first half of the early 20th century, the most influential Chamar leader was Swami Achutanand, who founded the anti-Brahmanical Adi Hindu movement, and portrayed the lower castes as the original inhabitants of India, who had been enslaved by Aryan invaders.[16][17]

Political rise

In the 1940s, the Indian National Congress promoted the Chamar politician Jagjivan Ram to counteract the influence of B.R. Ambedkar; however, he remained an aberration in a party dominated by the upper castes.[18] In the second half of the 20th century, the Ambedkarite Republican Party of India (RPI) in Uttar Pradesh remained dominated by Chamars/Jatavs, despite attempts by leaders such as B.P. Maurya to expand its base.[19]

After the decline of the RPI in the 1970s, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) attracted Chamar voter base. It experienced electoral success under the leadership of the Chamar leaders Kanshi Ram and Mayawati; Mayawati who eventually became the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.[20] Other Dalit communities, such as Bhangis, complained of Chamar monopolisation of state benefits such as reservation.[21] Several other Dalit castes, resenting the domination of Dalit politics by Chamars/Jatavs, came under the influence of the Sangh Parivar.[22]

Nevertheless, with the rise of BSP in Uttar Pradesh, a collective solidarity and uniform Dalit identity was framed, which led to coming together of various antagonistic Dalit communities. In the past, Chamar had shared bitter relationship with the Pasis, another Dalit caste. The root cause of this bitter relationship was their roles in feudal society. The Pasis worked as lathail or stick wielders for the "Upper Caste" landlords and the later had compelled them in past to beat Chamars many a times. Under the unification drive of BSP, these rival castes came together for the cause of unity of Dalits under same political umbrella.[23]

Dhusia

Dhusia is a caste in India, sometimes associated with Chamars, Ghusiya, Jhusia or Jatav.[24][25] They are found in Uttar Pradesh,[26] and elsewhere.

Most of the Dhusia in Punjab and Haryana migrated from Pakistan after partition of India. In Punjab, they are mainly found in Ludhiana, Patiala, Amritsar and Jalandhar cities. They are inspired by B. R. Ambedkar to adopt the surname Rao[27] and Jatav.

Occupations

Chamars transitioning from tanning and leathercraft to the weaving profession adopt the identity of Julaha Chamar, aspiring to be acknowledged as Julahas by other communities. According to R. K. Pruthi, this change reflects a desire to distance themselves from the perceived degradation associated with leatherwork.[28]

Chamar Regiment

The 1st Chamar Regiment was an infantry regiment formed by the British during World War II. Officially, it was created on 1 March 1943, as the 27th Battalion 2nd Punjab Regiment. It was converted to the 1st Battalion and later disbanded shortly after World War II ended.[29] The Regiment, with one year of service, received three Military Crosses and three Military Medals[30] It fought in the Battle of Kohima.[31] In 2011, several politicians demanded that it be revived.[32]

Demographics

According to the 2001 census of India, the Chamars comprise around 14 per cent of the population in the state of Uttar Pradesh[33] and 12 per cent of that in Punjab.[34]

| State | Population | State Population % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Bengal[35] | 999,756 | 1.25% | |

| Bihar[36] | 4,090,070 | 5% | |

| Delhi[37] | 893,384 | 6.45% | |

| Chandigarh[38] | 48,159 | 5.3% | |

| Chhattisgarh[39] | 1,659,303 | 8% | |

| Gujarat[40] | 1,032,128 | 1.7% |

In Gujarat also known as Bhambi, Asodi, Chamadia, Harali, Khalpa, Mochi, Nalia, Madar, Ranigar, Ravidas, Rohidas, Rohit, Samgar.[40] Gujarat's government has made an effort to change their name from 'Chamar' to 'Rohit' and to change the name of their villages and towns from 'Chamarvas' to 'Rohitvas'.[41] |

| Haryana[42] | 2,079,132 | 9.84% | Known as Jatav |

| Himachal Pradesh[43] | 414,669 | 6.8% | |

| Jammu & Kashmir[44] | 488,257 | 4.82% | |

| Jharkhand[45] | 837,333 | 3.1% | |

| Madhya Pradesh[46] | 837,333 | 9.3% | Chamars are primarily concentrated in Sagar, Morena, Rewa,

Bhind and Chhatarpur districts. Chamars work in land measurement are described as Balahi.[47] Balahi have major concentration in Ujjain, Khargone and Dewas districts. |

| Maharashtra[48] | 1,234,874 | 1.28% | |

| Punjab[49] | 2,800,000 | 11.9% | The Chamar caste cluster (34.93%) consists of two castes of Chamars and Ad-dharmis. Chamar—an umbrella caste category—includes Chamars, Jatia Chamars, Rehgars, Raigars, Ramdasias, and Ravidassias.[50] |

| Rajasthan[51] | 6,100,236 | 10.8% | Chamars in Rajasthan can only be identified in the districts adjoining to the states of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. The districts of Bikaner, Shriganganagar, Hanumangarh, Churu, Jhunjhunu, Alwar, Bharatpur and Dhaulpur are inhabited by Chamars. In the districts of Bharatpur, Dhaulpur and parts of Alwar (adjoining to Bharatpur) they are known as Meghwal[52][page needed] Raigar (leather tanners) and Mochi (shoe makers) are other two castes related to the leather profession.[citation needed]In Bikaner region, they are known as Balai.[53] |

| Uttar Pradesh[54] | 19,803,106 | 14% | |

| Uttarakhand[55] | 444,535 | 5% |

The 2011 Census of India for Uttar Pradesh combined the Chamar, Dhusia, Jhusia, Jatava Scheduled Caste communities and returned a population of 22,496,047.[56]

Caste reservation

Chamar is classified as a scheduled caste in India. It is largely believed that among the scheduled castes, Chamar benefitted more from the caste reservation system as compared to Valmikis, Bhangis and other Dalit castes due to larger political representation of the group.[57]

Chamars in Nepal

The Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal classifies the Chamar as a subgroup within the broader social group of Madheshi Dalits.[58] At the time of the 2011 Nepal census, 335,893 people (1.3% of the population of Nepal) were Chamar. The frequency of Chamars by province was as follows:

- Madhesh Province (4.2%)

- Lumbini Province (2.1%)

- Koshi Province (0.3%)

- Bagmati Province (0.0%)

- Gandaki Province (0.0%)

- Karnali Province (0.0%)

- Sudurpashchim Province (0.0%)

The frequency of Chamars was higher than national average (1.3%) in the following districts:[59]

Notable people

- Jagjivan Ram, former Deputy Prime Minister of India[60]

- Kanshi Ram (1934–2006), founder of Bahujan Samaj Party and mentor of Mayawati Kumari[61]

- Mayawati, leader of Bahujan Samaj Party and Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.[62]

- Mohan Lal Kureel was a British Indian Army officer who served in The Chamar Regiment and later an Indian National Congress politician in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.[63]

See also

References

- ^ "List of Scheduled Castes" (PDF). Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. p. 18. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Dr V.Vasanthi Devi (2021). A Crusade for Social Justice. South Vision Books. p. 253.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Yadav, Bhupendra (21 February 2012). "Aspirations of Chamars in North India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ Malu, Preksha (21 July 2018). "Caste-igated: How Indians use casteist slurs to dehumanise each other". Sabrang Communications. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Twitter Calls out Netflix's 'Jamtara' for Using Casteist Slur". The Quint. 18 January 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Singh, Sanjay L. (20 August 2008). "Calling an SC 'chamar' offensive, punishable, says apex court". The Economic Times. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Case Studies on Strengthening Co-ordination Between Non-governmental Organizations and Government Agencies in Promoting Social Development. United Nations (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific). 1989. p. 72,73,74,75. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Kaushal Kishore Sharma; Prabhakar Prasad Singh; Ranjan Kumar (1994). Peasant Struggles in Bihar, 1831-1992: Spontaneity to Organisation. Centre for Peasant Studies. p. 247. ISBN 9788185078885.

According to them, before the emergence of Naxalism on the scene and consequent resistance on the part of these hapless fellows, "rape of lower caste women by Rajput and Bhumihar landlords used to cause so much anguish among the lower cates, who, owing to their hapless situation, could not dare oppose them. In their own words, "within the social constraints , the suppressed sexual hunger of the predominant castes often found unrestricted outlet among the poor, lower caste of Bhojpur-notably Chamars and Mushars.

- ^ E M Rammohun; Amritpal Singh; A K Agarwal (2012). Maoist Insurgency and India's Internal Security Architecture. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 18. ISBN 978-9381411636. Retrieved 12 June 2022. Consider the oppression of the lower castes in Bihar. In Bhojpur district of Bihar, the lower castes lived in utter poverty and were also subjected to social exploitation. Kalyan Mukherjee and Rajender Singh Yadav described that the oppression of the lower castes at the hands of the upper castes did not flow from numerical superiority, but rather from niches in the economic hierarchy apropos land ownership and the monopoly over labour. Further the culture of violence ensured that the Chamar or the Musahar never raise their heads in protest. Though begar was a thing of the past, the banihar worked often for nothing. Wearing a clean dhoti, remaining seated in the presence of the master, even on a cot outside his own hut, walking erect were taboo. When the evenings fell or in lonely stretches of field, the rape of his womenfolk by the landlord's lathieths and scions complete a picture of unbridled Bumihar, Rajput over lordship.

- ^ Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp 2011, p. 106.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 5,33.

- ^ Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 43, 76.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 45.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 7, 23.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, pp. 8, 24.

- ^ Sarah Beth Hunt 2014, p. 55,72.

- ^ Badri Narayan (2012). Women Heroes and Dalit Assertion in North India: Culture, Identity and Politics. SAGE. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780761935377.

- ^ "Lokniti" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "The Inhabitants". sultanpur.nic.in. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009.

- ^ "Social Justice" (PDF).

- ^ Verma, A. K. (December 2001). "UP: BJP's Caste Card". Economic and Political Weekly. 36 (48): 4452–4455. JSTOR 4411406.

- ^ Pruthi, R. K. (2004). Indian caste system. Discovery. p. 189. ISBN 9788171418473. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Sharma 1990, p. 28.

- ^ Sharma, Gautam (1990). Valour and Sacrifice: Famous Regiments of the Indian Army. Allied Publishers. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-81-7023-140-0.

- ^ "The Battle of Kohima" (PDF).

- ^ "RJD man Raghuvansh calls for reviving Chamar Regiment". indianexpress.com. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Uttar Pradesh data highlights: the Scheduled Castes, Census of India 2001" (PDF).

- ^ "Uttar Pradesh data highlights: the Scheduled Castes" (PDF).

- ^ "West Bengal — DATA HIGHLIGHTS: THE SCHEDULED CASTES — Census of India 2001" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - Delhi comments.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ a b "State and district-wise Scheduled Castes population for each caste separately, 2011 - GUJARAT".

- ^ Dave, Nayan (8 October 2016). "'Rohits' to replace Chamars in Gujarat". Gandhinagar: The Pioneer.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh (21 July 2018). Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 9788177552577 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ Ram, Ronki (21 January 2017). "Internal Caste Cleavages among Dalits in Punjab". Economic & Political Weekly. 52 (3).

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ Rawat, Shyam (2010). Studies in Social Protest. VEDAMS. ISBN 978-8131603314.

- ^ Gupta, R. K.; Bakshi, S. R. (2008). Balai: Chamars in Bikaner region are known as Balai. Sarup & Sons. ISBN 9788176258418.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "Census table" (PDF). www.censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ "A-10 Individual Scheduled Caste Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix - Uttar Pradesh". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Rajinder Puri (3 February 2022). "Who Gains From Reservation?". Outlook India.

- ^ Population Monograph of Nepal, Volume II

- ^ "2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2016). "Indian society and the soldier: will the twain ever meet?". In Pant, Harsh V. (ed.). Handbook of Indian Defence Policy: Themes, structures and doctrines. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-1138939608. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

In 1970, when Babu Jagjivan Ram (himself, a chamar) became the defence minister, he attempted to raise the chamar regiment.

- ^ "I will be the best PM and Mayawati is my chosen heir". Indian Express. 2 May 2003.

...I am a chamar from Punjab...

- ^ "Mayawati talks of a secret successor". India Today. Indo-Asian News Service. 9 August 2008. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "SC Commission Asks Defence Secretary Why 'Chamar Regiment' Shouldn't be reinstated". News18. March 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

Bibliography

- Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp (2011). Peter Schalf (ed.). Neuer Buddhismus als gesellschaftlicher Entwurf (PDF). Uppsala University. doi:10.1515/olzg-2015-0120. ISBN 978-91-554-8076-9. S2CID 164806488.

- Sarah Beth Hunt (2014). Hindi Dalit Literature and the Politics of Representation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73629-9.

Further reading

- Briggs, George W. (1920). The Religious Life of India — The Chamars. Calcutta: Association Press. ISBN 1-4067-5762-4.

- Rawat, Ramnarayan S. (2011). Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253222626.

- Schmalz, Mathew N. (2004). "A Bibliographic Essay on Hindu and Christian Dalit Religiosity". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. 17: 55–65. doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1318.