Carthage (/ˈkɑːrθɪdʒ/ KAR-thij; Arabic: قرطاج, romanized: Qarṭāj) is a commune in Tunis Governorate, Tunisia. It is named for, and includes in its area, the archaeological site of Carthage.

Carthage

قرطاج | |

|---|---|

Partial view of the modern municipality from Amilcar in Sidi Bou Said | |

| Coordinates: 36°51′18″N 10°19′50″E / 36.85500°N 10.33056°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Tunis Governorate |

| Delegation(s) | Carthage |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Hayet Bayoudh (Tahya Tounes) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Omar Fendri |

| Area | |

| • Total | 180 km2 (70 sq mi) |

| Population (2014)[1] | |

| • Total | 24,216 |

| • Density | 130/km2 (350/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| Website | www |

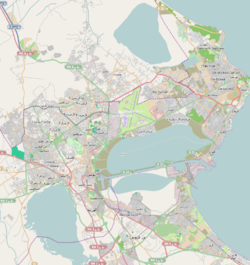

Established in 1919, Carthage is some 15 km to the east-northeast of Tunis, situated between the towns of Sidi Bou Said to the north and Le Kram to the south. It is reached from Tunis by the R23 road via La Goulette, or by the N9 road via Tunis–Carthage International Airport.

The population as of January 2013 was estimated at 21,277,[2] mostly attracting the more wealthy residents.[3] The Carthage Palace (the Tunisian presidential palace) is located on the coast.[4]

Carthage has six train stations of the TGM line between Le Kram and Sidi Bou Said: Carthage Salammbo (named for the ancient children's cemetery where it stands), Carthage Byrsa (named for Byrsa hill), Carthage Dermech (Dermèche), Carthage Hannibal (named for Hannibal), Carthage Présidence (named for the Presidential Palace) and Carthage Amilcar (named for Hamilcar).

History

editRoman Carthage was destroyed following the Muslim invasion of 698, and it remained under the control of the Arabs and later Ottoman rule for more than a thousand years (being replaced in the function of regional capital by the Medina of Tunis), until the establishment of the French protectorate of Tunisia in 1881.

The cathedral of St. Louis of Carthage was built on Byrsa hill in 1884. In 1885, Pope Leo XIII acknowledged the revived Archdiocese of Carthage as the primatial see of Africa and Charles Lavigerie as primate.[5][6] European-style villas were built along the beach beginning in 1906; one such villa was chosen by Habib Bourguiba as the presidential palace in 1960.

The municipality was created by a decree of the Bey of Tunis on 15 June 1919,[7] during the rule of Naceur Bey.

Construction on the Tunis–Carthage International Airport, which was fully funded by France, began in 1944, and in 1948 the airport become the main hub for Tunisair.

In the 1950s, the Lycée Français de Carthage was established to serve French families in Carthage. In 1961, it was given to the Tunisian government as a part of the Independence of Tunisia, so the nearby Collège Maurice Cailloux in La Marsa, previously an annex of the Lycée Français de Carthage, was renamed to the Lycée Français de La Marsa and began serving the lycée level. It is currently the Lycée Gustave Flaubert.[8]

After Tunisian independence in 1956, the Tunis conurbation gradually extended around the airport, and Carthage is now a suburb of Tunis.[9][10]

In February 1985, Ugo Vetere, the mayor of Rome, and Chedly Klibi, the mayor of Carthage, signed a symbolic treaty "officially" ending the conflict between their cities, which had been supposedly extended by the lack of a peace treaty for more than 2,100 years.[11]

The office of mayor was held by Chedli Klibi from 1963 to 1990, by Fouad Mebazaa from 1995 to 1998 and by Sami Tarzi from 2003 to 2011, and by Azedine Beschaouch from 2011.[12] The monumental Malik ibn Anas mosque (also El Abidine mosque; (جامع مالك بن أنس (سابقا جامع العابدين) )), built on an area of three hectares on Odéon hill, was inaugurated in 2003.[13]

See also

edit- Ancient Carthage

- Carthage (archaeological site)

- History of Carthage

References

edit- ^ (in French) Population estimate of 2013 Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine National Institute of Statistics – Tunisia

- ^ "Statistical Information: Population". National Institute of Statistics – Tunisia. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2014.; up from 15,922 in 2004 ("Population, ménages et logements par unité administrative" (in French). National Institute of Statistics – Tunisia. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2014.)

- ^ David Lambert, Notables des colonies. Une élite de circonstance en Tunisie et au Maroc (1881-1939), éd. Presses universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 2009, pp. 257-258. (in French) Sophie Bessis, « Défendre Carthage, encore et toujours », Le Courrier de l'Unesco, septembre 1999 Archived 2007-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "More Tunisia unrest: Presidential palace gunbattle". philSTAR.com. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Joseph Sollier, "Charles-Martial-Allemand Lavigerie" Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1910) Jenkins, Philip (2011). The next christendom : the coming of global Christianity (3rd ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780199767465.

- ^ Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1910). "Lavigerie, Charles Martial Allemand". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 6 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 425. In 1964, the episcopal see of Carthage had to be de-established again, in a compromise reached with the government of Habib Bourguiba, which permitted the Catholic Church in Tunisia to retain legal personality and representation by the prelate nullius of Tunis...

- ^ "Creation Date". commune-carthage.gov.tn. 2014. Archived from the original on 2023-10-26. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ "Qui sommes nous ?" (Archive). Lycée Gustave Flaubert (La Marsa). Retrieved on February 24, 2016.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (January 1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa. Taylor & Francis. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-884964-03-9.

- ^ Illustrated Encyclopaedia of World History. Mittal Publications. p. 1615. GGKEY:C6Z1Y8ZWS0N.

- ^ "written by John Lawton". Archived from the original on 2009-02-05. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ « Dissolution de 22 conseils municipaux et désignation de délégations spéciales », Leaders, 19 avril 2011 Archived 2011-04-21 at Wikiwix Organigramme de l'administration municipale (Municipalité de Carthage) Archived December 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Liste des maires de Carthage (Municipalité de Carthage) Archived December 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ « La mosquée El Abidine, Carthage », Architecture méditerranéenne, hors-série « La Tunisie moderne : deux décennies de transformations », novembre 2007, p. 51-57

External links

editMedia related to Carthage at Wikimedia Commons