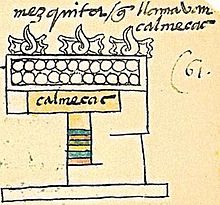

The Calmecac ([kaɬˈmekak], from calmecatl meaning "line/grouping of houses/buildings" and by extension a scholarly campus) was a school for the sons of Aztec nobility (pīpiltin [piːˈpiɬtin]) in the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, where they would receive rigorous training in history, calendars, astronomy, religion, economy, law, ethics and warfare. The two main primary sources for information on the calmecac and telpochcalli are in Bernardino de Sahagún's Florentine Codex of the General History of the Things of New Spain (Books III, VI, and VIII) and part 3 of the Codex Mendoza.[1]

Telpcatli Calmecac

editThe calmecac of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, was located in the ceremonial centre of the city and was dedicated to Quetzalcoatl.[2] It was situated conveniently close to the Templo Mayor, where calmecac graduates destined for priesthood would perform the rituals they had been trained in. The main shrine was judged to be 150 feet tall and was a larger structure than the Templo Mayor.[3] The calmecac's courtyard roof featured prominently visible motifs in the shape of spirals, each of which reached eight feet in height.[4] Aztec rulers built their own individual versions of the calmecac upon the preceding one. These seven buildings were discovered in the mid 2000s when a team of archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) began working on the site as part of History's Urban Archaeology Program (PAU) after the 1985 earthquake damaged the area.[3]

Attendance

editThe calmecac was typically reserved for sons of Aztec noblemen, while the young commoner men, macehualtin, received military training in the Tēlpochcalli ([teːɬpot͡ʃˈkalːi] "house of youth").[5] The placement of noble youth in the telpochcalli might have been by lesser wives' or concubines' sons or younger sons, perhaps of commoner status so that the boys did not have to compete with noble youths in the calmecac.[6] However, although the calmecac has been characterized as for elites only, Sahagun's account says that at times the macehualtin were assigned to the calmecac as well and trained for the priesthood.[7][2] Codex Mendoza's account of the calmecac emphasizes the possibilities of upward mobility for young commoner men, (macehualtin), educated in the telpochcalli. Promising sons of nobles would be trained especially by the military orders of the Jaguar warriors (ōcēlōmeh [oːseːˈloːmeʔ]) or Eagle warriors (cuāuhtin [ˈkʷaːʍtin]) in their quarters, the cuāuhcalli ([kʷaːʍˈkalːi]).[8] Codex Mendoza's account largely ignores class distinctions between the calmecac and the telpochcalli.[9] Emperor Moctezuma II was educated at and graduated from Tenochtitlan's calmecac.[10]

-

In the 2000s the remains of Tenochtitlan's calmecac were located beneath the Spanish Cultural Center in downtown Mexico City.

-

Basement museum with the partially excavated ruins of Tenochtitlan's calmecac.

Student life, education, and training

editStudents as young as five to seven years of age would enter the calmecac, which would be their home for the duration of their training. The parents brought their children to the calmecac to partake in a dedication ceremony in the presence of the calmecac and telpochcalli authorities.[11] In a series of rituals that lasted hours, the new students were bathed, named, and marked upon the hip and chest to "designate their adult role."[11] After the children's ears had been pierced and the ceremony was concluded, the Aztec temple held a celebratory feast.[11]

Instruction at the calmecac did not begin gradually. Four-year-olds were immediately introduced to adult ceremonies, with discipline and punishment beginning at the age of seven.[11] The students received instruction in songs, rituals, reading and writing, the calendar (tōnalpōhualli [toːnaɬpoːˈwalːi]) and all the basic training which was also taught in the telpochcalli. The priests oversaw all aspects of the students' education, preparing the children for a variety of careers outside of priesthood. Elite students, in particular, could progress to multiple jobs within the Aztec government, including academic, economic, judicial, diplomatic, and administrative roles.[12] Students commenced formal military training around age fifteen.[13] While the calmecac served primarily as a center for religious and military instruction in order to swell both ranks with diligent and skilled priests and soldiers, students also "learned various manual skills."[14]

Etymology, symbolism, and social impact

editThe name calmecac is a combination of the words calli, meaning "house," and the word mecatl, meaning "cords, ropes, whips."[4] Taken together, calmecac can be read as "the house of whips or penitence."[4] It has also been directly translated as the Nahuatl word for school.[3] The cords were sometimes made of malinall grass and used in acts of penance. Piercing parts of the body with sharp grass or other implements was done to connect with the cosmos and preserve eternal unity. This unity was visibly symbolised by spirals, or cutaway shell motifs.[4] The spirals featured on the Tenochtitlan calmecac were designed to look like snails and symbolised the unity intrinsic to the Aztec religion.[3] After Spanish invaders destroyed the capital's calmecac, their artwork misrepresented the spirals as much smaller. When archaeologist Raúl Barrera uncovered seven of the rooftop spirals during the PAU excavation, the ornaments became "one of the most distinctive motifs of ancient Mexico.[3]

The calmecac tied together the military, political and sacred hierarchies of the community.[15] Schools that qualified as calmecacs furthered the Aztec religion and forms of government and ensured continued stability by training the society's youth in academic, political, and military skills. In addition to the calmecac in Tenochtitlan, rural villages throughout the Aztec empire would have had calmecacs of their own, ensuring that all civilians had access to comprehensive instruction in religious practice.[16][14]

Notes

edit- ^ Edward Calneck, "The Calmecac and Telpochcalli in Pre-Conquest Tenochtitlan," in The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico, J. Jorge Klor de Alva et al., eds. Albany: SUNY Albany Institute for Mesoamerican Studies 1988, p. 170.

- ^ a b Hassig (1988), p.34.

- ^ a b c d e Atwood, Roger (2014). "Under Mexico City". Archaeology. 67 (4): 26–33 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Maffie, James (2013). Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. pp. 162, 277, 377–378.

- ^ Calnek, "Calmecac and Telpochcalli", p. 169.

- ^ Calnek, "Calmecac and Telpochcalli", p. 176.

- ^ Edward Calneck, "The Calmecac and Telpochcalli" p. 169.

- ^ Hassig (1988), p.36.

- ^ Calnek, "Calmecac and Telpochcalli", p. 177.

- ^ Atwood, Roger (2014). "Under Mexico City". Archaeology. 67 (4): 26–33. JSTOR 43825230. Retrieved 2022-10-01.

- ^ a b c d Joyce, Rosemary A. (2000). "Girling the Girl and Boying the Boy: The Production of Adulthood in Ancient Mesoamerica". World Archaeology. 31 (3): 473–483. doi:10.1080/00438240009696933. PMID 16475297. S2CID 10658152 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Classen Cheryl, Laura Ammon (2022). Religion in sixteenth-century Mexico: a guide to Aztec and Catholic beliefs and practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 219, 234, 241, 268, 297, 340.

- ^ Hassig (1988), p.35.

- ^ a b Hicks, Frederic (2012). "Governing small communities in Aztec Mexico". Ancient Mesoamerica. 23 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1017/S095653611200003X. S2CID 163011554 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Carrasco, Pedro. (2001). "Calmecac". In Davíd Carrasco (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, vol 1. New York : Oxford University Press.

- ^ Baca, Damián (2009). "Rethinking Composition, Five Hundred Years Later". JAC. 29 (1/2): 229–242. doi:10.2199/jjsca.29.229 – via JSTOR.

References

edit- Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel (2007). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533083-0. OCLC 81150666.

- Andrews, J. Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3452-6. OCLC 50090230.

- Calnek, Edward. "The Calmecac and Telpochcalli in Pre-Conquest Tenochtitlan" in The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico, J. Jorge Klor de Alva et al., eds. Albany: SUNY Albany Institute for Mesoamerican Studies 1988.

- Carrasco, Pedro. "Calmecac". In Davíd Carrasco (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, vol 1. New York : Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780195108156

- Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 188. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2121-1. OCLC 17106411.

- León-Portilla, Miguel (1980). Native Mesoamerican Spirituality: Ancient myths, discourses, stories, doctrines, hymns, poems from the Aztec, Yucatec, Quiché-Maya and other sacred traditions. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-0293-5. OCLC 6450751.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de (1997) [ca.1558–61]. Primeros Memoriales. Civilization of the American Indians series vol. 200, part 2. Thelma D. Sullivan (English trans. and paleography of Nahuatl text), with H.B. Nicholson, Arthur J.O. Anderson, Charles E. Dibble, Eloise Quiñones Keber, and Wayne Ruwet (completion, revisions, and ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2909-9. OCLC 35848992.

- Van Tuerenhout, Dirk R. (2005). The Aztecs: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO's understanding ancient civilizations series. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-921-X. OCLC 57641467.