β2 microglobulin (B2M) is a component of MHC class I molecules. MHC class I molecules have α1, α2, and α3 proteins which are present on all nucleated cells (excluding red blood cells).[5][6] In humans, the β2 microglobulin protein[7] is encoded by the B2M gene.[6][8]

Structure and function

editβ2 microglobulin lies beside the α3 chain on the cell surface. Unlike α3, β2 has no transmembrane region. Directly above β2 (that is, further away from the cell) lies the α1 chain, which itself is next to the α2.

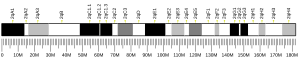

β2 microglobulin associates not only with the alpha chain of MHC class I molecules, but also with class I-like molecules such as CD1 (5 genes in humans), MR1, the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), and Qa-1 (a form of alloantigen). Nevertheless, the β2 microglobulin gene is outside of the MHC (HLA) locus, on a different chromosome.

An additional function is association with the HFE protein, together regulating the expression of hepcidin in the liver which targets the iron transporter ferroportin on the basolateral membrane of enterocytes and cell membrane of macrophages for degradation resulting in decreased iron uptake from food and decreased iron release from recycled red blood cells in the MPS (mononuclear phagocyte system) respectively. Loss of this function causes iron excess and hemochromatosis.[9]

In a cytomegalovirus infection, a viral protein binds to β2 microglobulin, preventing assembly of MHC class I molecules and their transport to the plasma membrane.[citation needed]

Mice models deficient for the β2 microglobulin gene have been engineered. These mice demonstrate that β2 microglobulin is necessary for cell surface expression of MHC class I and stability of the peptide-binding groove. In fact, in the absence of β2 microglobulin, very limited amounts of MHC class I (classical and non-classical) molecules can be detected on the surface (bare lymphocyte syndrome or BLS). In the absence of MHC class I, CD8+ T cells cannot develop. (CD8+ T cells are a subset of T cells involved in the development of acquired immunity.)[citation needed]

Clinical significance

editIn patients on long-term hemodialysis, it can aggregate into amyloid fibers that deposit in joint spaces, a disease, known as dialysis-related amyloidosis.

Low levels of β2 microglobulin can indicate non-progression of HIV.[10]

Levels of β2 microglobulin can be elevated in multiple myeloma and lymphoma, though in these cases primary amyloidosis (amyloid light chain) and secondary amyloidosis (amyloid associated protein) are more common.[clarification needed] The normal value of β2 microglobulin is < 2 mg/L.[11] However, with respect to multiple myeloma, the levels of β2 microglobulin may also be at the other end of the spectrum.[12] Diagnostic testing for multiple myeloma includes obtaining the β2 microglobulin level, for this level is an important prognostic indicator. As of 2011[update], a patient with a level < 4 mg/L is expected to have a median survival of 43 months, while one with a level > 4 mg/L has a median survival of only 12 months.[13] β2 microglobulin levels cannot, however, distinguish between monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), which has a better prognosis, and smouldering (low grade) myeloma.[14][15]

Loss-of-function mutations in this gene have been reported in cancer patients unresponsive to immunotherapies.[citation needed]

Virus relevance

editβ2 microglobulin has been shown to be of high relevance for viral entry of Coxsackievirus A9 and Vaccinia virus (a Poxvirus).[16] For Coxsackievirus A9, it is likely that β2 microglobulin is required for the transport to plasma membrane of the identified receptor, the Human Neonatal Fc Receptor (FcRn).[17] However, the specific function for Vaccinia virus has not yet been elucidated.

References

edit- ^ a b c ENSG00000273686 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000166710, ENSG00000273686 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000060802 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: Beta-2-microglobulin".

- ^ a b Güssow D, Rein R, Ginjaar I, Hochstenbach F, Seemann G, Kottman A, et al. (November 1987). "The human beta 2-microglobulin gene. Primary structure and definition of the transcriptional unit". Journal of Immunology. 139 (9): 3132–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.139.9.3132. PMID 3312414. S2CID 38290153.

- ^ Cunningham BA, Wang JL, Berggård I, Peterson PA (November 1973). "The complete amino acid sequence of beta 2-microglobulin". Biochemistry. 12 (24): 4811–22. doi:10.1021/bi00748a001. PMID 4586824.

- ^ Suggs SV, Wallace RB, Hirose T, Kawashima EH, Itakura K (November 1981). "Use of synthetic oligonucleotides as hybridization probes: isolation of cloned cDNA sequences for human beta 2-microglobulin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (11): 6613–7. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.6613S. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.11.6613. PMC 349099. PMID 6171820.

- ^ Hundall SD (2011). "Chapter 3: Iron, Heme, and Hemoglobin". Hematology: A Pathophysiologic Approach (1st ed.). Elsevier - Health Sciences Division. pp. 17–25. ISBN 978-0-323-04311-3.

- ^ Rao M, Sayal SK, Uppal SS, Gupta RM, Ohri VC, Banerjee S (October 1997). "Beta-2-Microglobulin Levels in Human-Immunodeficiency Virus Infected Subjects". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 53 (4): 251–254. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(17)30746-3. PMC 5531080. PMID 28769505.

- ^ Pignone M, Nicoll D, McPhee SJ (2004). Pocket guide to diagnostic tests (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 191. ISBN 0-07-141184-4.

- ^ "Amyloidosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Munshi NC, Longo DL, Anderson KC (2011). "Chapter 111: Plasma Cell Disorders". In Loscalzo J, Longo DL, Fauci AS, Dennis LK, Hauser SL (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 936–44. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ^ Rajkumar SV (2005). "MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma: update on pathogenesis, natural history, and management". Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2005: 340–5. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.340. PMID 16304401.

- ^ Bataille R, Klein B (November 1992). "Serum levels of beta 2 microglobulin and interleukin-6 to differentiate monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance". Blood. 80 (9): 2433–4. doi:10.1182/blood.V80.9.2433.2433. PMID 1421418.

- ^ Matía A, Lorenzo MM, Romero-Estremera YC, Sánchez-Puig JM, Zaballos A, Blasco R (27 December 2022). "Identification of β2 microglobulin, the product of B2M gene, as a Host Factor for Vaccinia Virus Infection by Genome-Wide CRISPR genetic screens". PLOS Pathogens. 18 (12): e1010800. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1010800. PMC 9829182. PMID 36574441.

- ^ Zhao X, Zhang G, Liu S, Chen X, Peng R, Dai L, et al. (May 2019). "Human Neonatal Fc Receptor Is the Cellular Uncoating Receptor for Enterovirus B". Cell. 177 (6): 1553–1565.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.035. PMC 7111318. PMID 31104841.

Further reading

edit- Huang WC, Havel JJ, Zhau HE, Qian WP, Lue HW, Chu CY, et al. (September 2008). "Beta2-microglobulin signaling blockade inhibited androgen receptor axis and caused apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells". Clinical Cancer Research. 14 (17): 5341–7. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0793. PMC 3032570. PMID 18765525.

- Huang WC, Wu D, Xie Z, Zhau HE, Nomura T, Zayzafoon M, et al. (September 2006). "beta2-microglobulin is a signaling and growth-promoting factor for human prostate cancer bone metastasis". Cancer Research. 66 (18): 9108–16. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1996. PMID 16982753.

- Winchester JF, Salsberg JA, Levin NW (October 2003). "Beta-2 microglobulin in ESRD: an in-depth review". Advances in Renal Replacement Therapy. 10 (4): 279–309. doi:10.1053/j.arrt.2003.11.003. PMID 14681859.

- Krangel MS, Orr HT, Strominger JL (December 1979). "Assembly and maturation of HLA-A and HLA-B antigens in vivo". Cell. 18 (4): 979–91. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(79)90210-1. PMID 93026.

- Okon M, Bray P, Vucelić D (September 1992). "1H NMR assignments and secondary structure of human beta 2-microglobulin in solution". Biochemistry. 31 (37): 8906–15. doi:10.1021/bi00152a030. PMID 1390678.

- Guo HC, Jardetzky TS, Garrett TP, Lane WS, Strominger JL, Wiley DC (November 1992). "Different length peptides bind to HLA-Aw68 similarly at their ends but bulge out in the middle". Nature. 360 (6402): 364–6. Bibcode:1992Natur.360..364G. doi:10.1038/360364a0. PMID 1448153. S2CID 4324984.

- Gattoni-Celli S, Kirsch K, Timpane R, Isselbacher KJ (March 1992). "Beta 2-microglobulin gene is mutated in a human colon cancer cell line (HCT) deficient in the expression of HLA class I antigens on the cell surface". Cancer Research. 52 (5): 1201–4. PMID 1737380.

- Saper MA, Bjorkman PJ, Wiley DC (May 1991). "Refined structure of the human histocompatibility antigen HLA-A2 at 2.6 A resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 219 (2): 277–319. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(91)90567-P. PMID 2038058.

- Caruana RJ, Lobel SA, Leffell MS, Campbell H, Cheek PL (December 1990). "Tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and beta 2-microglobulin levels in chronic hemodialysis patients". The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 13 (12): 794–8. doi:10.1177/039139889001301205. PMID 2289831. S2CID 24952854.

- Connors LH, Shirahama T, Skinner M, Fenves A, Cohen AS (September 1985). "In vitro formation of amyloid fibrils from intact beta 2-microglobulin". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 131 (3): 1063–8. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(85)90198-6. PMID 2413854.

- Hochman JH, Shimizu Y, DeMars R, Edidin M (April 1988). "Specific associations of fluorescent beta-2-microglobulin with cell surfaces. The affinity of different H-2 and HLA antigens for beta-2-microglobulin". Journal of Immunology. 140 (7): 2322–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.140.7.2322. PMID 2450918. S2CID 34035543.

- Homma N, Gejyo F, Isemura M, Arakawa M (1989). "Collagen-binding affinity of beta-2-microglobulin, a preprotein of hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis". Nephron. 53 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1159/000185699. PMID 2674742.

- Bataille R, Grenier J, Commes T (1988). "In vitro production of beta 2 microglobulin by human myeloma cells". Cancer Investigation. 6 (3): 271–7. doi:10.3109/07357908809080649. PMID 3048575.

- Hönig R, Marsen T, Schad S, Barth C, Pollok M, Baldamus CA (November 1988). "Correlation of beta-2-microglobulin concentration changes to changes of distribution volume". The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 11 (6): 459–64. PMID 3060434.

- Bjorkman PJ, Saper MA, Samraoui B, Bennett WS, Strominger JL, Wiley DC (1987). "Structure of the human class I histocompatibility antigen, HLA-A2". Nature. 329 (6139): 506–12. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..506B. doi:10.1038/329506a0. PMID 3309677. S2CID 4373217.

- Güssow D, Rein R, Ginjaar I, Hochstenbach F, Seemann G, Kottman A, et al. (November 1987). "The human beta 2-microglobulin gene. Primary structure and definition of the transcriptional unit". Journal of Immunology. 139 (9): 3132–8. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.139.9.3132. PMID 3312414. S2CID 38290153.

- Cunningham BA, Wang JL, Berggård I, Peterson PA (November 1973). "The complete amino acid sequence of beta 2-microglobulin". Biochemistry. 12 (24): 4811–22. doi:10.1021/bi00748a001. PMID 4586824.

- Suggs SV, Wallace RB, Hirose T, Kawashima EH, Itakura K (November 1981). "Use of synthetic oligonucleotides as hybridization probes: isolation of cloned cDNA sequences for human beta 2-microglobulin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (11): 6613–7. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.6613S. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.11.6613. PMC 349099. PMID 6171820.

- Momoi T, Suzuki M, Titani K, Hisanaga S, Ogawa H, Saito A (May 1995). "Amino acid sequence of a modified beta 2-microglobulin in renal failure patient urine and long-term dialysis patient blood". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 236 (2): 135–44. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(95)06039-G. PMID 7554280.

- Collins EJ, Garboczi DN, Karpusas MN, Wiley DC (February 1995). "The three-dimensional structure of a class I major histocompatibility complex molecule missing the alpha 3 domain of the heavy chain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (4): 1218–21. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.1218C. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.4.1218. PMC 42670. PMID 7862664.

- Matoba R, Okubo K, Hori N, Fukushima A, Matsubara K (September 1994). "The addition of 5'-coding information to a 3'-directed cDNA library improves analysis of gene expression". Gene. 146 (2): 199–207. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90293-3. PMID 8076819.

- Wang Z, Cao Y, Albino AP, Zeff RA, Houghton A, Ferrone S (February 1993). "Lack of HLA class I antigen expression by melanoma cells SK-MEL-33 caused by a reading frameshift in beta 2-microglobulin messenger RNA". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 91 (2): 684–92. doi:10.1172/JCI116249. PMC 288010. PMID 8432869.

External links

edit- beta+2-Microglobulin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human B2M genome location and B2M gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P61769 (Beta-2 microglobulin) at the PDBe-KB.