Benzatropine (INN[2]), known as benztropine in the United States and Japan,[3] is a medication used to treat movement disorders like parkinsonism and dystonia, as well as extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics, including akathisia.[4] It is not useful for tardive dyskinesia.[4] It is taken by mouth or by injection into a vein or muscle.[4] Benefits are seen within two hours and last for up to ten hours.[5][6]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cogentin, others |

| Other names | benzatropine (BAN UK), benztropine (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous |

| Drug class | Antimuscarinic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 12–24 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

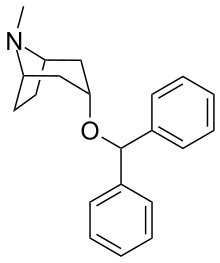

| Formula | C21H25NO |

| Molar mass | 307.437 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include dry mouth, blurry vision, nausea, and constipation.[4] Serious side effect may include urinary retention, hallucinations, hyperthermia, and poor coordination.[4] It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[7] Benzatropine is an anticholinergic which works by blocking the activity of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.[4]

Benzatropine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1954.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In 2020, it was the 229th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[8][9] It is sold under the brand name Cogentin among others.[4]

Medical uses

editBenzatropine is used to reduce extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic treatment. Benzatropine is also a second-line drug for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. It improves tremor, and may alleviate rigidity and bradykinesia.[10] Benzatropine is also sometimes used for the treatment of dystonia, a rare disorder that causes abnormal muscle contraction, resulting in twisting postures of limbs, trunk, or face.

Adverse effects

editThese are principally anticholinergic:

- Dry mouth

- Blurred vision

- Cognitive changes

- Drowsiness

- Constipation

- Urinary retention

- Tachycardia

- Anorexia

- Severe delirium and hallucinations (in overdose)

While some studies suggest that use of anticholinergics increases the risk of tardive dyskinesia (a long-term side effect of antipsychotics),[11][12] other studies have found no association between anticholinergic exposure and risk of developing tardive dyskinesia,[13] although symptoms may be worsened.[14]

Drugs that decrease cholinergic transmission may impair storage of new information into long-term memory. Anticholinergic agents can also impair time perception.[15]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

editAntihistamine and anticholinergic activity

editBenzatropine is a centrally acting anticholinergic and antihistamine. In terms of its anticholinergic activity, it is specifically an antimuscarinic and acts a selective muscarinic acetylcholine M1 and M3 receptor antagonist.[16] Benzatropine partially blocks cholinergic activity in the basal ganglia. Animal studies have indicated that anticholinergic activity of benzatropine is approximately one-half that of atropine, while its antihistamine activity approaches that of mepyramine. Its anticholinergic effects have been established as therapeutically significant in the management of Parkinsonism. Benzatropine antagonizes the effect of acetylcholine, decreasing the imbalance between the neurotransmitters acetylcholine and dopamine, which may improve the symptoms of early Parkinson's disease.[17]

Benzatropine has been also identified, by a high throughput screening approach, as a potent differentiating agent for oligodendrocytes, possibly working through M1 and M3 muscarinic receptors. In preclinical models for multiple sclerosis, benzatropine decreased clinical symptoms and enhanced re-myelination.[18]

Atypical dopamine reuptake inhibition

editIn addition to its anticholinergic activity, benztropine has been found to increase the availability of dopamine by blocking its reuptake and storage in central sites, and as a result, increasing dopaminergic activity. Benzatropine and analogues are atypical dopamine reuptake inhibitors,[19] which might make them useful for people with akathisia secondary to antipsychotic therapy.[20]

Other actions

editBenzatropine also acts as a functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase (FIASMA).[21]

Other animals

editIn veterinary medicine, benzatropine is used to treat priapism in stallions.[22]

Naming

editSince 1959, benzatropine is the official international nonproprietary name of the medication under the INN scheme, the medication naming system coordinated by the World Health Organization; it is also the British Approved Name (BAN) given in the British Pharmacopoeia,[2][3] and has been the official nonproprietary name in Australia since 2015.[23] Regional variations of the "a" spelling are also used in French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish, as well as Latin (all medications are assigned a Latin name by WHO).[3]

"Benztropine" is the official United States Adopted Name (USAN), the medication naming system coordinated by the USAN Council, co-sponsored by the American Medical Association (AMA), the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA). It is also the Japanese Accepted Name (JAN)[24] and was used in Australia until 2015, when it was harmonized with the INN.[23]

Both names may be modified to account for the methanesulfonate salt as which the medication is formulated: the modified INN (INNm) and BAN (BANM) is benzatropine mesilate, while the modified USAN is benztropine mesylate.[25] The modified JAN is a hybrid form, benztropine mesilate.[24]

The misspelling benzotropine is also occasionally seen in the literature.

References

edit- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (December 1959). "International Non-Proprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Preparations). Recommended International Non-Proprietary Names (Rec. I.N.N.): List 3º" (PDF). WHO Chronicle. 13 (12): 464. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization. "INN: Benzatropine". WHO MedNet. Retrieved 1 December 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Benztropine Mesylate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Pagliaro LA, Pagliaro AM (1999). PNDR, Psychologists' Neuropsychotropic Drug Reference. Psychology Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780876309568.

- ^ Aschenbrenner DS, Venable SJ (2009). Drug Therapy in Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 197. ISBN 9780781765879.

- ^ "Benztropine (Cogentin) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Benztropine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ DiMascio A, Bernardo DL, Greenblatt DJ, Marder JE (May 1976). "A controlled trial of amantadine in drug-induced extrapyramidal disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry. 33 (5): 599–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770050055008. PMID 5066.

- ^ Kane JM, Smith JM (April 1982). "Tardive dyskinesia: prevalence and risk factors, 1959 to 1979". Archives of General Psychiatry. 39 (4): 473–481. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290040069010. PMID 6121548. S2CID 10194153.

- ^ Wszola BA, Newell KM, Sprague RL (August 2001). "Risk factors for tardive dyskinesia in a large population of youths and adults". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 9 (3): 285–296. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.9.3.285. PMID 11534539.

- ^ van Harten PN, Hoek HW, Matroos GE, Koeter M, Kahn RS (April 1998). "Intermittent neuroleptic treatment and risk for tardive dyskinesia: Curaçao Extrapyramidal Syndromes Study III". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (4): 565–567. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.4.565. PMID 9546009.

- ^ Yassa R (September 1988). "Tardive dyskinesia and anticholinergic drugs. A critical review of the literature". L'Encéphale. 14 Spec No (Spec No): 233–239. PMID 3063514.

- ^ Gelenberg AJ, Van Putten T, Lavori PW, Wojcik JD, Falk WE, Marder S, et al. (June 1989). "Anticholinergic effects on memory: benztropine versus amantadine". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 9 (3): 180–185. doi:10.1097/00004714-198906000-00004. PMID 2661606. S2CID 27308127.

- ^ Lakstygal AM, Kolesnikova TO, Khatsko SL, Zabegalov KN, Volgin AD, Demin KA, et al. (May 2019). "DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Atropine, Scopolamine, and Other Anticholinergic Deliriant Hallucinogens". ACS Chem Neurosci. 10 (5): 2144–2159. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00615. PMID 30566832.

- ^ MIMS Australia Pty Ltd. MIMS.

- ^ Deshmukh VA, Tardif V, Lyssiotis CA, Green CC, Kerman B, Kim HJ, et al. (October 2013). "A regenerative approach to the treatment of multiple sclerosis". Nature. 502 (7471): 327–332. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..327D. doi:10.1038/nature12647. PMC 4431622. PMID 24107995.

- ^ Hiranita T, Kohut SJ, Soto PL, Tanda G, Kopajtic TA, Katz JL (January 2014). "Preclinical efficacy of N-substituted benztropine analogs as antagonists of methamphetamine self-administration in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 348 (1): 174–191. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.208264. PMC 3868882. PMID 24194527.

- ^ Adler LA, Peselow E, Rosenthal M, Angrist B (1993). "A controlled comparison of the effects of propranolol, benztropine, and placebo on akathisia: an interim analysis". Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 29 (2): 283–286. PMID 8290678.

- ^ Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, et al. (2011). "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623852K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. PMC 3166082. PMID 21909365.

- ^ Wilson DV, Nickels FA, Williams MA (November 1991). "Pharmacologic treatment of priapism in two horses". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 199 (9): 1183–1184. doi:10.2460/javma.1991.199.09.1183. PMID 1752772.

- ^ a b "Updating medicine ingredient names - list of affected ingredients". Therapeutic Goods Administration. 23 November 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ a b Compound D00778 at KEGG Pathway Database.

- ^ Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Antiparkinsonian Drugs". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 797. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.