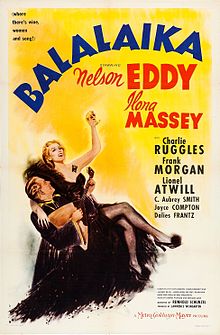

Balalaika is a 1939 American musical romance film based on the 1936 London stage musical of the same name.[1] Produced by Lawrence Weingarten and directed by Reinhold Schunzel, it starred Nelson Eddy and Ilona Massey.

| Balalaika | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Reinhold Schünzel |

| Written by | Leo Gordon Charles Bennett Jacques Deval |

| Based on | Balalaika by Eric Maschwitz |

| Produced by | Lawrence Weingarten |

| Starring | Nelson Eddy Ilona Massey |

| Cinematography | Ernst Matray Joseph Ruttenberg Karl Freund |

| Edited by | George Boemler |

| Music by | George Posford Bernard Grun Herbert Stothart |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The film follows the romance of Prince Peter Karagin and Lydia Pavlovna Marakova, a singer and secret revolutionary, in Imperial Russia on the eve of World War I. Douglas Shearer was nominated for the 1939 Academy Award for Best Sound Recording.[2]

Plot

editIn 1914 Tsarist Russia, Prince Peter Karagin is a captain of the Cossack Guards, riding home from manoeuvres to an evening of wine, women and song at St. Petersburg's Cafe Balalaika. The Balalaika's new star, Lydia Pavlovna Marakova, is blackmailed into attending the officers' party and is expected to choose a "favoured one." She intrigues Karagin when she makes good her escape instead.

Masquerading as a poor music student, Karagin insinuating himself into Lydia's family and circle of musician friends, unaware that they are dedicated revolutionaries. He discovers his larcenous orderly, Nikki Poppov, courting the Marakovs' maid, Masha. Karagin then bullies Ivan Danchenoff, Director of the Imperial Opera, into giving Lydia an audition; Danchenoff is pleasantly surprised to find that (unlike the 60 other women foisted on him by other aristocrats) she has real talent. Later, Karagin orders his usual arrangements for seduction, but falls in love instead and tries to cancel them. She understands both his former and current motives, and admits she loves him too.

Their happiness ends when Lydia's brother Dimitri is killed after giving a seditious speech on the street by Cossacks led by Peter, whom Lydia recognizes. When she learns that her opera debut will be used as an opportunity to assassinate Peter and his father the general, she makes Peter promise not to come or let his father come to the performance, pretending she would be too nervous with them watching. The two men attend anyway. Fortunately, General Karagin receives a message that Germany has declared war on Russia and announces it to the crowd. Professor Makarov, Lydia's father, decides not to shoot because the general will be needed to defend Mother Russia. However, Leo Proplinski feels otherwise, grabs the pistol and shoots the general, though not fatally. Peter finally learns of Lydia's political beliefs when she is arrested. Later, he has her released.

Peter goes to fight as an officer in the trenches. When the Russian Revolution overthrows the old regime, he winds up in 1920s Paris employed by his former orderly as a cabaret entertainer at the new "Balalaika". To celebrate the Russian Orthodox New Year, White Russians, wearing court dress and paste jewels, gather as Poppov's guests. When Poppov makes Peter stand before a mirror, candle in hand, to make the traditional New Year's wish to see his "true love," Lydia appears behind him.

Cast

edit- Nelson Eddy as Prince Peter Karagin, aka "Peter Illyich Teranda"

- Ilona Massey as Lydia Pavlovna Marakova

- Charlie Ruggles as Corporal Nicki Popoff

- Frank Morgan as Ivan Danchenoff

- Lionel Atwill as Prof. Pavel Marakov

- C. Aubrey Smith as Gen. Karagin

- Joyce Compton as Masha, the Marakovs' maid and later Nicki's wife

- Dalies Frantz as Dimitri Marakov

- Walter Woolf King as Capt. Michael Sibirsky, Peter's friend

- Abner Biberman as Leo Proplinski

- Arthur W. Cernitz as Capt. Sergei Pavloff

- Roland Varno as Lt. Nikitin

- George Tobias as Slaski (bartender)

- Phillip Terry as Lt. Smirnoff

- Frederick Worlock as Ramensky

- Roland Varno as Lt. Nikitin

- Paul Sutton as Anton (waiter)

- Willy Castello as Capt. Testoff

- Paul Irving as Prince Morodin

- Mildred Shay as Jeanette Sibirsky

- Alma Kruger as Mrs. Danchenoff

- Zeffie Tilbury as Princess Natalya Petrovna

Among the uncredited cast are:

- Maurice Cass

- Feodor Chaliapin Jr., son of the famous Russian operatic bass, as Soldier

- Al Ferguson as Soldier

- Jack George as Violinist

- Charles Judels as Batoff

- Michael Mark

- Paul Newlan as Policeman

- Irra Petina

- Lee Phelps as Doorman

- Frank Puglia as Ivan (Troika Inn owner)

- Hector Sarno

- Harry Semels

- Florence Shirley as Lily Allison (Paris tourist)

- Ellinor Vanderveer

Musical score

editOnly the musical's title song, "At the Balalaika," with altered lyrics, was used in the film. MGM had music director Herbert Stothart adapt material it already owned or was otherwise available, or write original material as needed.[3]

List of musical numbers in order of appearance:

| Title | Source(s) | Performers |

|---|---|---|

| Overture | At the Balalaika (verse), Tanya, At the Balalaika (chorus) | orchestra |

| Russian religious chant | copyrighted as "After Service;" arranged by Herbert Stothart | chorus |

| Life for the Tsar | fragment, Mikhail Glinka, A Life for the Tsar, Act III | male chorus |

| Ride, Cossacks, Ride | music Herbert Stothart; lyrics Bob Wright, Chet Forrest | male chorus, Eddy, Walter Woolf King, male soloists, whistling by Sergei Protzenko |

| Life for the Tsar | reprise | Eddy and male chorus |

| Tanya | music Herbert Stothart, lyrics Bob Wright and Chet Forrest | Massey, male chorus |

| "Gorko" | Russian drinking song adapted by Herbert Stothart | male chorus, Massey |

| At the Balalaika | from the original London production: music George Posford, lyrics Eric Maschwitz; new lyrics Wright and Forrest | Massey, male chorus |

| Polonaise in A Flat, Opus 53 | Frédéric Chopin | Dalies Frantz, piano |

| "El Ukhnem" | traditional, arranged Feodor Chaliapin and Feodor Feodorovich Koenemann | Eddy, male chorus |

| "Chanson Boheme" | Opera Carmen: Act II. music Georges Bizet, libretto Henri Meilhac, Ludovic Halevy | Massey |

| "Chanson du Toreador"

("The Toreador Song") |

see above | Eddy |

| "Si Tu M'Aime" | Carmen: Act IV. see above | Eddy and Massey |

| Tanya | see above | orchestral reprise |

| Music from Scheherazade

Shadows on the Sand |

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, arranged as an opera by Bob Wright and Chet Forrest.

MGM copyrighted Miss Massey's solo as Shadows on the Sand. |

Massey, Sigurd Nilssen, Irra Petina, Douglas Beattie, David Laughlin |

| "Bozhe, Tsarya khrani"

(God Save the Tsar) |

Imperial Russian Anthem. Music Alexei Fedorovich Lvov, lyrics Vasili Andreevitch Zhukovsky | chorus, Eddy, C. Aubrey Smith, and Massey |

| At the Balalaika | reprise | King |

| "Stille Nacht" | music Franz Gruber, lyrics Joseph Mohr | Eddy and male chorus |

| "Otchi Chornia" | lyrics Yevhen Hrebinka, set to Florian Hermann's "Valse Hommage" arrangement by S. Gerdel') | Massey |

| At the Balalaika | reprise | Eddy |

| Land of Dreams | not given | Frank Morgan, male trio |

| Flow, Flow, White Wine

[lyric: "Bubbles in the Wine"] |

King, Frank Morgan, arranged Stothart, lyrics Kahn | Eddy |

| Wishing Episode

[lyric: "Mirror, Mirror"] |

arranged Stothart, lyrics Wright and Forrest | Alma Kruger, Mildred Shay, Eddy |

| Magic of Your Love | music Franz Lehár; new lyrics Gus Kahn, Clifford Grey.

Originally "The Melody of Love" from Lehar's Gypsy Love. (Sung with new lyrics as "The White Dove" in The Rogue Song with Lawrence Tibbett, MGM, 1930. |

chorus, Eddy and Massey |

| Finale: Song of the Volga Boatman | see above | orchestral reprise |

A number of additional songs were copyrighted for the film, but apparently not used.[4]

Production notes

editVarious sources agree that MGM was planning to make this film two years before production actually began. Filming started in June 1939, although Eddy and Massey spent the four weeks prior to shooting pre-recording their musical numbers.[5]

Miliza Korjus was offered the role of Lydia but "thought it was a joke." She turned it down on the assumption Eddy would again be teamed with Jeanette MacDonald,[6] apparently unaware that both Eddy and MacDonald were demanding solo star roles from the studio, or that the studio had agreed.[7] She was devastated to learned that Ilona Massey had accepted the role, losing the opportunity to work with "that gorgeous hunk of baritone".[6]

Censorship

editLike all films of the era, Balalaika was subject to censorship by the Production Code Administration. Beginning with a December 1937 letter to Louis B. Mayer, Joseph Breen opened with a suggestion that the film not offend "...the citizens or government of any country..." before detailing what could not appear in the film: a prostitute, sale or discussion of pornography, all risque dialog, and reference to a male secretary as a "pansy". In addition "... mob violence... must avoid... details of brutality and gruesomeness."[8] Notwithstanding, the audience had plenty of clues to fill in the blanks.

Critical reception

editPreviewed on December 15, 1939, most critics agreed that the stars and production were excellent, even if the script and plot were not.[4] Many went on to prophesy a glowing career for Massey – here in her first starring role – which never took off.[3] Frank S. Nugent's review in The New York Times praised Massey's blond good looks and Eddy's competence: "She looks like Dietrich, talks like Garbo... while leaving the bulk of (the score) safely to Mr. Eddy..."

Despite enjoying the romantic escapism and musical artistry, Nugent foresaw international repercussions. "In these propaganda-searching days, we know the comrades are going to howl bloody Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The notion of peasant girls tossing their locks and eyes at the Imperial Guard and the film's gusty sighing over the dear dead days... are bound to be tantamount to waving a papal bull before the Red flag of The Daily Worker."

Nor did he overlook the film's shortcomings, "...the picture is long on formula and short on originality... nine out of ten sequences have been blue-printed before," but nonetheless gave director Reinhold Schunzel credit for a job well done.[9]

References

edit- ^ "Balalaika". Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ "The 12th Academy Awards (1940) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- ^ a b "Turner Classic Movies".

- ^ a b "Jeanette and Nelson". Archived from the original on 2009-06-04.

- ^ "Balalaika (1939): Notes". Turner Classic Movies, UK. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ a b "Baritone Corner". Arabella and Co. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ Parish, James Robert; Pitts, Michael R. (January 2003). Hollywood Songsters: Allyson to Funicello by James Robert Parish, Michael R. Pitts - page 282. Routledge. ISBN 9780415943321.

- ^ Robinson, Harlow (2007). Russians in Hollywood, Hollywood's Russians: biography of an image by Harlow Robinson. ISBN 9781555536862.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (December 15, 1939). "THE SCREEN IN REVIEW By FRANK S. NUGENT, December 15, 1939". New York Times. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012.