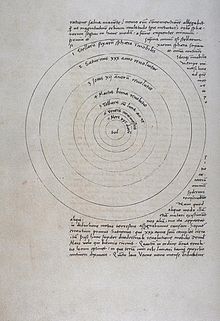

The autograph of Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus is a manuscript of six books of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) by Nicolaus Copernicus written between 1520 and 1541.[1] Since 1956, it is kept in the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków (signature 10,000).[2]

The autograph was handwritten by Nicolaus Copernicus in Latin and Greek, using humanistic cursive. The manuscript consists of 213 paper leaves sized 28 × 19 centimeters, two endpapers, and four protective cards. The binding of the manuscript dates back to the early 17th century and is made of cardboard glued with waste paper and a parchment document from the 16th century.[3]

It is a unique object on a global scale, inscribed in 1999 on the UNESCO Memory of the World list.[4] It is also the most valuable and famous autograph kept in the collections of the Jagiellonian Library of the Jagiellonian University, of which it has been the property since 1956.

The text of the autograph, which was first published in 1543 in Nuremberg in the first edition of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, revolutionized the perception of the universe from a historical point of view and was a starting point for modern astronomy and science.[5]

Description edit

The autograph contains the text of the six books authored by Nicolaus Copernicus that make up the work De revolutionibus.[3]

Contents of the manuscript of De revolutionibus[3] edit

| Number | Number of a book | Leaves included in a book |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Book I | 1 – 26 |

| 2 | Book II | 26 verso – 70 verso |

| 3 | Book III | 71 – 106 |

| 4 | Book IV | 106 verso – 141 verso |

| 5 | Book V | 142 – 188, 197 verso – 201 verso |

| 6 | Book VI | 188 verso – 197, 203 – 212 verso |

Leaf 1 contains the incipit: (I)nter multa ac varia litteraturum artiumaque studia, Leaf 1 verso: Capitulum primum. Quod mundus sit sphaericus. Principio advertendum nobisest globusm est mundum.[3]

Leaf 212 verso contains the explicit: remanebit praepollens latitudo quaesita.[3]

Provenance notes edit

The endpaper of the front cover contains an ex libris with the coat of arms of the Nostitz family and the inscription:

Ex Bibliotheca Maioratus Familiae Nostitzianae 1774[3][6][7]

Below the ex libris, there is a note written in ink over the previous one made in pencil, stating:

Das Manuscript enthält: 212 Blätter, ausserdem 3 Vorblätter von denen das 1-e leer ist, das 2-e die Aufzählung der verschiedenen Eigenthümer und das 3-e Blatt den Namhen Otto F. v. Nostitz[3][6]

The inserted leaf b contains a note attributed to Jakob Christmann:

Venerabilis et eximii Iuris utriusque Doctoris, Dni Nicolai Copernick Canonici Varmiensis, in Borussia Germaniae mathematici celeberrimi opus de revolutionibus coelestibus propria manu exparatum et haectenus in bibliotheca Georgii Ioachimii Rhetici item Valentini Othonis conservatum, ad usum studii mathematici procurauit M. Iakobus Christmannus Decanus Facultatis artium, anno 1603, die 19 Decembris[7][8]

The reverse side of leaf b contains a note by John Amos Comenius:

Hunc librum a vidua pie defuncti M. Jac. Cristmanni digno redemptum pretio, in suam transtulit Bibliothecam Johannes Amos Nivanus: Anno 1614. 17 Januarii. Heidelbergae.[7][9]

On leaf c, there is the signature Otto F. v. Nostitz mp.[7][10]

Paper edit

The manuscript consists of four types of paper with characteristic watermarks designated in the literature by letters: C, D, E, and F.[11] These symbols were used in their descriptions by Ludwik Birkenmajer, followed by his son Aleksander Birkenmajer.[11]

Types of paper used for the manuscript of De revolutionibus[3] edit

| Number | Designation | Characteristics | Example | Origin of paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paper C | watermark – snake with a fleuron | around 1520–1525, presumably Netherlands | |

| 2 | Paper D | watermark – hand with fingers spread under the crown | around 1523–1530, presumably France | |

| 3 | Paper E | watermark – letter P with a fleuron above it | around 1537–1540, Maastricht (Netherlands) | |

| 4 | Paper F | watermark – hand with tight fingers with a three-leaf clover | 1538 Osnabrück, 1540 Lotharingia |

Papers of different types occur irregularly in the manuscript.[12]

Type C paper edit

Paper C is the oldest used in the manuscript.[11] Its watermark depicts a rather thick snake, resembling the stance and curvature of a seahorse, with its head bent beyond the axis towards the margin, while its tail points in the opposite direction, although its end is also directed towards the margin.[11] On the snake's head, there is a fleur-de-lis resembling a crown, and a tongue protrudes from its mouth directed upwards and ending in a blade-shaped tip.[11] The snake's body is divided by a dorsal line into two parts, which are further divided into segments by oblique horizontal lines descending downwards.[11] In Charles Briquet's catalogue, the most similar watermark is cataloged as number 10,738.[13][14]

As established, this watermark was often found on papers from southern France, Spain, and Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries.[13] However, the most similar ones to those found in the De revolutionibus manuscript were discovered on paper known from Middelburg from 1525. There, an even earlier paper was discovered, with a watermark featuring a similar depiction of the snake's tongue, dated to 1520.[13]

Dating the paper is also facilitated by the fact that the text written on paper C, on leaf 88 verso, discusses an astronomical observation made by Copernicus on 11 March 1516.[13] The occurrence of paper C ends on leaf 89.[13]

Type D paper edit

Paper D contains a watermark depicting a hand protruding from a cross with 9 pinnacles, with fingers raised upwards and spread out, placed beneath a crown.[13] This paper is of inferior quality.[15] Analysis of watermarks on similar paper has shown its origin from the town of Tulle in France, dating back to the years 1523 and 1526.[15] Presumably, this paper reached Copernicus through the Netherlands, similar to paper C.[15] In Charles Briquet's catalogue, the most similar watermarks are cataloged as number 10,944[15][16] and 10,946.[16]

On paper D, Copernicus provided information and comments on astronomical observations from 27 September 1522 (leaf 128), 22 February 1523 (leaf 166), and 12 March 1529 (leaf 173).[15] It is assumed that this paper was used by Copernicus from 1523 to 1533.[15] Paper D occurs between leaves 9 and 192.[13]

Type E paper edit

Paper E contains a watermark in the shape of the letter P, with a fleuron placed above it.[15] This watermark is almost identical to the one known from Maastricht in 1540. However, this paper reached Copernicus earlier, as he wrote letters in August 1537 and March 1539, and extensive portions of the manuscript were written on this paper before 1540.[15] Paper E occurs between leaves 22 and 213.[15] In Charles Briquet's catalogue, the most similar watermark is cataloged as number 8,698.[15][17][18]

Type F paper edit

Paper F contains a watermark similar to the one on paper D.[15] It depicts a hand with fingers spread out, with a sleeve ending in a circular fold, above which is a three-leaf clover.[15] This watermark has been identified in full accordance with other watermarks on papers from Osnabrück from 1538 and from Lorraine from 1540.[12] Copernicus used the same paper in a letter to Duke Albert of Prussia dated 15 June 1541.[12] Pages from paper F were therefore used in either 1540 or 1541.[12]

In Charles Briquet's catalogue, the most similar watermark is cataloged as number 11,466.[12][19] This watermark appears only once – on leaf 24, but paper F was used three times – on leaves 24, 25, and 209.[12][15]

Sections edit

The paper block containing Copernicus' autograph is divided into 21 sections, which were marked in the 16th century with consecutive letters of the Latin alphabet from a to x.[12] The numbering of the pages in individual sections was probably added around 1854 in the Nostitz Library, as the list of the number and completeness of the manuscript's leaves placed under the ex libris dates from the same year.[20]

Characteristics of sections in the manuscript of De revolutionibus[21] edit

| Number | Designation of section | Type of paper | Leaf numbers | Type of section | Leaves layout | Irregularities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | C, D | 1 – 9 | quinternion | leaf 0 cut out | |

| 2 | b | D | 10 – 19 | quinternion | ||

| 3 | c | D, E, F | 20 – 31 | sexternion | ||

| 4 | d | D, E | 32 – 39 | quaternion | ||

| 5 | e | C, D, E | 40 – 51 | sexternion | ||

| 6 | f | C | 52 – 61 | quinternion | ||

| 7 | g | C | 62 – 70 | quinternion | leaf 69 cut out | |

| 8 | h | C, E | 71 – 82 | sexternion | ||

| 9 | i | C, D, E | 83 – 94 | sexternion | ||

| 10 | k | D, E | 95 – 104 | quinternion | ||

| 11 | l | D, E | 105 – 114 | quinternion | ||

| 12 | m | D, E | 115 – 124 | quinternion | ||

| 13 | n | D | 125 – 134 | quinternion | ||

| 14 | o | D, E | 135 – 144 | quinternion | ||

| 15 | p | D, E | 145 – 154 | quinternion | leaf 146 cut out and pasted | |

| 16 | q | D, E | 155 – 164 | quinternion | ||

| 17 | r | D, E | 165 – 174 | quinternion | ||

| 18 | s | D, E | 175 – 184 | quinternion | ||

| 19 | t | D, E | 185 – 194 | quinternion | ||

| 20 | v | E | 195 – 202 | quaternion | ||

| 21 | x | E, F | 203 – 213 | sexternion | leaf 206 cut out |

The notation of the sections with letters occurred in the final stage of editing the autograph.[22] Aleksander Birkenmajer expressed the view that for many years of working on the autograph, Copernicus completely managed without any numbering of its leaves or notebooks.[22]

The letter signatures of the sections, except for the letter a on leaf 1, were applied by Copernicus in 1539.[22]

Researchers paid particular attention to the absence of the first leaf from paper D in section a, which was very carefully cut out – almost without a visible trace – and its remaining edge was glued to the preceding protective leaf.[22]

Aleksander Birkenmajer leans towards the view that the leaf, conventionally called zero, served for some time as the title page of Copernicus' work.[22] Presumably, the leaf was removed during the binding of the manuscript, in 1603 or 1604 in Heidelberg.[22]

The content of the zero leaf remains unknown. It is not known whether it contained only the title written by Copernicus' hand, or perhaps a dedication or notes about the history of the autograph or its successive owners.[22] It cannot be ruled out that the zero leaf contained some glaring damage, stains, or doubtful notes.[22] The structure of the autograph itself and the changes made by Copernicus in individual sections suggest that if Copernicus himself removed the zero leaf, he would have replaced it with another leaf and corrected the content on it.[22]

Copernicus made frequent changes in the structure of the sections. He most often exchanged and rewrote sheets, and sometimes added additional leaves within the section.[23] As a result, various types of paper from different periods of its acquisition are encountered in different sections.[24]

Writing edit

The autograph is written by the hand of Nicolaus Copernicus in humanistic cursive.[3] Marginalia and interlinear notes made by Georg Joachim Rheticus are found on leaves 21, 24, 71, 72, 188, and presumably 87 verso and 187 verso.[3] Leaves 107 verso and 109 contain marginalia – two words written in the 17th century, attributed to Jakob Christmann.[3]

One of the primary pieces of evidence supporting the assertion that this is Copernicus' handwritten autograph is a note attributed to Jakob Christmann: Nicolai Copernik [...] opus [...] propria manu exaratum.[25]

To confirm or exclude the authenticity of Nicolaus Copernicus' handwriting, various autographs of Copernicus were examined, including, in particular, his letters, which serve as unquestionable and authoritatively attributed comparative material.[25] Six handwritten letters of Nicolaus Copernicus to Johannes Dantiscus, preserved in Kraków and held at the National Museum in Kraków, were selected for this analysis.[25] These letters were written over three years – 1536 and 1539 – between the ages of 63 and 66, and they bear his signature and date. The signature and handwriting are undoubtedly original.[25]

As a comparative material for De revolutionibus, handwritten notes made and signed by Copernicus, providing samples of his handwriting from the years 1503, 1511, 1512, 1513, 1518, 1521, and 1529, were also considered.[26] These notes, which raise no doubts about authorship or authenticity, have been preserved in the accounts of the Warmia Chapter and in the locational entries of Locationes mansorum desertorum.[26] Their chronology complements the chronology covered by Copernicus' letters.[26]

From the comparison of Copernicus' handwriting samples from 1503 to 1541, written between the ages of 30 and 68, it can be inferred that this is the handwriting of a mature individual, with well-formed shapes and no significant differences dependent on chronology.[26] There are no signs of immature handwriting in these examples, even in later years.[26]

During the examination of the De revolutionibus autograph, Birkenmajer identified certain differences depending on the speed at which Copernicus wrote:[26] Two ducts of handwriting appear in the autograph: a hasty but well-shaped and legible cursive, and a calmer, more vertical handwriting, which is a typical humanistic antiqua.[27]

The most noticeable are the characteristic shapes of letters, their inclinations, elements of cursive writing, the sweep of the handwriting, the direction of pen strokes, and the spacing of lines and margins.[27] The analysis also revealed that in certain periods and fixed records of the autograph, some characteristics became fixed.[27]

Copernicus did not adhere to the custom of a fixed number of lines per page, as professional copyists of manuscripts contemporaneous to him did.[28] The number of lines per page varies between 37 and 43.[28] The text block averages 19 centimeters in width and 28 centimeters in height.[28]

The autograph text is primarily written in ink shades ranging from brown to full black.[29] Red ink was used in the tables crossed out from leaves 15 verso to 70 verso.[30]

Examiners emphasize that the notation style indicates the writer's preference for order, cleanliness, and harmonious arrangement of text columns and accompanying drawings.[30] Despite the aesthetic form of the manuscript, some strange mistakes were found.[30] Between leaves 125 and 175, Copernicus incorrectly wrote the word iusta instead of iuxta at least six times.[30] This error was described as an interesting case of perpetuating a once-made mistake and unconsciously repeating it.[30]

Many ink stains and blots of various sizes appear on clean and carefully written leaves.[31] From their distribution, it is inferred that they were created during later erasures and corrections made in haste.[31]

Geometric drawings, of which there are 162 in the entire manuscript, distributed over 129 pages, also deserve attention.[31] The drawings are also made by the hand of Nicolaus Copernicus, as evidenced by the style of letters used to label them.[31] The drawings are made carefully, using a compass and ruler, although minor flaws occasionally occborn[31] Copernicus extensively uses lines in astronomical tables, which appear on 118 pages of the manuscript.[31]

The conclusion of the conducted research was that the handwriting of the De revolutionibus manuscript is – except for minor foreign annotations – the handwritten autograph of Nicolaus Copernicus.[32]

Binding edit

During the work on the De revolutionibus autograph, the section and leaves accumulated by Copernicus did not have a binding.[33] Presumably – according to the customs prevailing in that era – Copernicus stored loose sections of his work in a cover such as a bag, envelope, or folder made of leather or parchment. It could also have been a box or chest.[33] This is indicated by the significantly greater dirtiness of the external leaves of the sections, which was the result of their separate storage.[33]

The cover of the manuscript consists of 4 protective leaves (a, b, c, and d) and 2 endpapers. However, it is more accurate to consider that the manuscript has an endpaper and protective leaf a at the beginning and protective leaf e and endpaper at the end because leaves b and c are not strictly protective leaves but substitutes for a title page.[33]

Leaf a was made from paper A, while cards b, c, and e were made from paper B.[33]

The watermark of paper A depicts a large letter P, split at the bottom, with a rosette above it in the form of a four-petaled flower on a single stem. Below the letter is a faint drawing of an object – either a trumpet or a pine cone. In Briquet's catalog, the watermark most similar is cataloged as number 8,833.[33][34]

The watermark of paper B depicts a heraldic shield cut by a horizontal band, above which is a rod pointing upwards topped with a three-leaf clover entwined by a snake sticking out its long tongue. In Briquet's catalog, the watermark most similar is cataloged as number 1,451.[33][35]

These papers date from 1580 to 1600 and originate from Württemberg paper mills.[36]

During conservation work, after removing the endpaper, it was discovered that the cover made of cardboard consisting of parchment pulp under an external parchment cover contained a parchment document of Emperor Maximilian II from 1566 and a corrected printout of De inquisitione Hispanica, Heidelberg 1603.[3]

The fact that correction leaves of a book published in 1603 were found inside the cover proves that the cover certainly was not made before that year, and at the same time, its creation could not have been too far from the 1603/1604 transition.[37]

Before the binding from 1603/1604, the manuscript was neither sewn nor trimmed, and the current binding is its first binding.[38]

History of the manuscript edit

The preserved form of the De revolutionibus autograph represents a certain stage in the work on this piece. It is the stage closest to completion and closest to the death of Nicolaus Copernicus, which occurred on 24 May 1543.[38]

The preserved copy of the De revolutionibus autograph was not used for publishing purposes either in Wittenberg in 1542 or in Nuremberg in 1543 during the printing of the first edition, nor in Basel during the printing of the second edition.[39] This is evidenced by the cleanliness of the manuscript and the absence of traces associated with contemporary printing work such as stains, marks, etc.[39] Not only does the appearance of the manuscript indicate that it was not a copy used in the printing process, but also the lists of printer's errors included in the published copies and referring to a comparison with the manuscript, which contain words not present in the original autograph.[39]

Owners of the De revolutionibus manuscript and where it is stored[7] edit

| Number | Owner | Location | Ownership period |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nicolaus Copernicus (born 1473, died 1543) | Frombork | until his death in 1543 |

| 2 | Tiedemann Giese (born 1480, died 1550) | Warmia | from 1543 to 1545/1550 |

| 3 | Georg Joachim Rheticus (born 1514, died 1574) | Leipzig, Kraków, Košice | from 1545/1550 until his death in 1574 |

| 4 | Valentinus Otho (born around 1545, died around 1603) | Košice, Heidelberg | from 1574 until his death in 1603 |

| 5 | Jakob Christmann (born 1554, died 1613) i his widow | Heidelberg | from 1603 to 1613 |

| 6 | John Amos Comenius (born 1592, died 1670) | unknown | from 1613 to around 1665 |

| 7 | Otto von Nostitz (born 1608, died 1655) i his heirs | Jawor, Prague, Luboradz, unknown locations | before 1665 to 1945 |

| 8 | National Museum Library | Prague | from 1945 to 1965 |

| 9 | Jagiellonian University | Kraków | from 1965 |

Period from Copernicus' death to 1600 edit

After Copernicus' death, his papers and books were inherited by his close friend Tiedemann Giese, the Bishop of Chełmno, and later, from 1548, the Bishop of Warmia.[38] Giese passed away on 23 October 1550, and according to his will, his library was bequeathed to the Warmia Chapter.[38]

However, the De revolutionibus autograph did not end up in the chapter library. Instead, during Tiedemann Giese's lifetime, it came into the possession of Georg Joachim Rheticus (also known as von Lauchen). This could have happened as early as 1545 or as late as 1550.[39]

Rheticus actually had access to the content of the autograph in the form of a copy even earlier, when in 1540 he published the first account of Copernicus' work in Gdańsk in the Narratio prima.[39] He also used a copy of the De revolutionibus autograph when he published De lateribus et angulis triangulorum in Wittenberg in 1542, which was intended to be the second book of Copernicus' work for some time.[39]

The exact moment when Georg Joachim Rheticus received the De revolutionibus autograph remains unknown. What is certain is that the remaining collection of Copernican materials in Tiedemann Giese's possession was transferred to the Warmia Chapter library.[39]

Georg Joachim Rheticus undoubtedly played a major role in disseminating Copernicus' thoughts and works. It was under his influence that Copernicus agreed to publish his autograph and helped in making a copy of it. However, Copernicus did not directly pass on the autograph to Rheticus during his lifetime.[39]

In 1551, Rheticus had to urgently leave Leipzig and abandon his further career at the university. Eventually, in 1554, he found himself in Kraków.[40] Around 1569, Valentinus Otho, a student of Johannes Praetorius, joined Rheticus as his collaborator. During this time, the De revolutionibus autograph was in Kraków, together with Rheticus.[40]

Shortly before his death, Georg Joachim Rheticus left Kraków for Košice, where he stayed as a guest of Albrecht Łaski, the voivode of Sieradz, and the Hungarian magnate Jan Rüber.[40] During Rheticus' stay in Košice, Valentinus Otho brought the De revolutionibus manuscript from Kraków, left there by Rheticus. This happened on 28 November 1574. A few days later, on 4 December 1574, Georg Joachim Rheticus died, and Valentinus Otho became his heir and the next owner of the manuscript.[40]

Otho soon left Košice and sought new employment. He obtained a position as a professor of mathematics at the Calvinist University of Heidelberg.[40] During his stay there, the De revolutionibus manuscript and other papers acquired from Rheticus were stored haphazardly among stacks of other books and papers.[40] This disorderly state of storage was reported by Otho's associate, Bartholomaeus Pitiscus, in the preface to his work Thesaurus Mathematicus.[40]

From 1600 to 1945 edit

When Valentinus Otho died, his collections were acquired by the orientalist professor Jakob Christmann, who wrote a note on leaf b attributed to him, stating ad usum studii mathematici procuravit dated 16 December 1603.[40] It is likely that Christmann did not include the manuscript in the university library but instead kept it for personal use when Simon Petiscus, who held the chair of mathematics at the time, took possession of it.[41] Petiscus died in 1608, and at that point, the manuscript most likely returned to Christmann's possession.[41] Christmann unquestionably owned the manuscript at the time of his death on 16 June 1613, and his widow, who took over the manuscript, sold it to John Amos Comenius on 17 January 1614.

Comenius acquired the manuscript just over half a year after his enrollment at the Heidelberg University (which occurred on 19 June 1613).[41] The purchase transaction was completed for an unspecified "fair price" paid to Christmann's widow.[41] Comenius noted this information on leaf b verso of the manuscript, signing himself as Johannes Amos Nivanus (from his birthplace – Nivnice in Moravia).[41] It is known that he resided in Poland several times (Leszno 1626–1641, Elbląg 1642–1648, again Leszno 1648–1656), but it is not known whether he had the De revolutionibus manuscript with him during any of his stays.[41] The moment when Comenius lost Copernicus' autograph is also unknown.[41]

The next owner of the De revolutionibus autograph was Otto von Nostitz.[41] The autograph is mentioned in the inventory document of the Nostitz Library under the signature MS e 21 (leaf 360 verso) with an entry from 5 October 1667. This date is later than the moment when von Nostitz became the owner, as he had already passed away at the time of the entry, but he left his signature on the protective leaf c of the De revolutionibus autograph.[41] At that time, the manuscript was kept at Jawor Castle.[41]

Later on, along with the Nostitz Library, the autograph became part of the estate created by them and was transferred to the Nostitz Palace in Prague.[41] The autograph remained the property of the Nostitz family for nearly 300 years and was mentioned several times in the inventories of this library in the 17th and 18th centuries.[41]

From 1945 to the present day edit

In 1945, the Prague collections of the Nostitz family, along with the autograph of De revolutionibus, were nationalized.[20] Eleven years later, on 5 July 1956, the government of Czechoslovakia offered this artifact as a gift to the Polish nation.[20]

On 25 October 1956, the autograph of De revolutionibus by Nicolaus Copernicus was handed over to the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, and since then it has been kept in the special collections of the Jagiellonian Library.[20]

Owen Gingerich, who examined almost all copies of the first and second editions of De revolutionibus from 1543 from Nuremberg and from 1566 from Basel, and who saw the autograph in Kraków around 1976, states in his book that this priceless treasure was lent to Poland by Czechoslovakia, and the Poles simply kept it and deposited it in the Jagiellonian Library at the Alma Mater of Copernicus. Since it was not customary for one communist country to protest too vehemently against the conduct of a brother nation, the valuable manuscript remained in Poland.[42]

However, this opinion is not confirmed by the facts and is even contradictory to the findings in this regard made and conveyed by UNESCO.[43]

Autograph storage in modern times edit

The autograph of De revolutionibus is stored in a secured, fireproof vault, in a specially prepared room within the Jagiellonian Library, where a constant temperature and humidity are maintained.[43]

Protection of objects from special collections is one of the most important statutory obligations of the university and the Jagiellonian Library.[43] Direct access to the autograph of De revolutionibus is permitted only for scientific and editorial purposes.[43]

Access to this object is strictly controlled and limited. According to the regulations governing access to special collections, independent academic staff and individuals with a doctoral degree, doctoral students, adjuncts, and assistants with a master's degree can use them after presenting a letter of recommendation from their supervisor or academic advisor. Students preparing master's theses can also access them after presenting a letter of recommendation from their supervisor, and employees of scientific, cultural institutions, or publishing houses can access them after presenting a letter of recommendation or a certificate informing about the research topic and purpose. Individuals outside of the above groups can only access the special collections with the permission of the head of the manuscripts department.[44]

Due to its unique value and the need for protection from external factors, the autograph of De revolutionibus is rarely displayed in public exhibitions. The last time this occurred was in 2012 during the 6th European Congress of Mathematics, and previously in 2005 during the Lesser Poland Days of Cultural Heritage.[45]

During the last exhibition, the autograph of De revolutionibus, as one of the most valuable treasures, was exhibited only temporarily, after which, for safety and conservation reasons, it was replaced with facsimile editions.[45]

Facsimile editions edit

1944 – Munich edit

The facsimile was produced using the photolithography technique, in monochrome.[46] This edition does not capture all the details of the original and has been assessed as not possessing significant aesthetic qualities.[46]

Full bibliographic information for the edition: Nicolaus Copernicus, Gesamtausgabe, vol. 1: Opus de revolutionibus caelestibus manu propria. Faksimile-Wiedergabe, München, Berlin 1944. Introduction by Fritz Kubach, afterword by Karl Zeller.[46]

1972 – Kraków edit

Volume I of the Complete Works of Nicolaus Copernicus, also published in foreign languages (Latin 1973, French 1973, Russian 1973), containing images of all pages of the autograph, printed on third-class offset paper. The volume is accompanied by an introduction by Jerzy Zathey. The publication was initiated on the occasion of the five hundredth anniversary of Nicolaus Copernicus' birth in 1973.[47]

1974 – Hildesheim edit

Edition of De revolutionibus: mit einem Vorwort zur Gesamtausgabe und einem Vorbericht über das Manuskript – the first volume containing a facsimile of the autograph.[48]

1976 – Kraków edit

The reproduction was made using offset printing, using a halftone contact screen, ensuring full tonal compliance of the facsimile background with the original.[29] The contact screen used allowed for the preservation of writing shades from brown to black and faithful reproduction of even small dots, spots, and distortions.[29]

Printing was done on 120 gsm offset paper in shades adjusted to the four types of paper used in the manuscript.[29] The dimensions of the pages are faithful to the original and cropped according to the prototype.[29]

The fidelity of the reproduction to the original is as follows:

- Background texture – 95%

- Background shades – 90%

- Low black intensity writing texture – 85%

- Black writing texture and shades – 95%

- Red writing shade and texture – 95%

This facsimile version looks so authentic that some people mistake it for the original when viewing it.[42] Owen Gingerich mentions in his book about a certain bookseller from Chicago who donated the facsimile to the Adler Planetarium and wanted to deduct the value of the donation from taxes. Believing he was donating the original autograph of Copernicus, he asked Gingerich to appraise it.[42]

1996 – electronic Neurosoft edit

Published as a "digital reprint" of the autograph. The publication consists of a CD-ROM containing images of all manuscript pages. It also includes an article by Marian Zwiercan entitled The History of Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus Autograph.[49]

De revolutionibus autograph online edit

Images of all pages of Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus autograph are available in the online collections of the Jagiellonian Library.[50]

Autograph on the Memory of the World list edit

The manuscript of De revolutionibus handwritten by Nicolaus Copernicus has been inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World list since 1999, as one of twelve Polish objects on the list[51] and three hundred globally.

The entry emphasizes that De revolutionibus is one of the greatest achievements of an individual that shaped new eras and influenced the development of civilization and culture.[52]

References edit

- ^ "Nicholas Copernicus: "De revolutionibus"". pka.bj.uj.edu.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ "Poland- Nicolaus Copernicus's masterpiece "De revolutionibus libri sex." (ca 1520)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zathey (1972, p. 38)

- ^ "Nicolaus Copernicus' masterpiece "De revolutionibus libri sex"". unesco.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-03. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ^ Hart (1996, p. 100)

- ^ a b Kopernik, Mikołaj. "Wyklejka w: De revolutionibus" (in Latin). Archived from the original on 1997-05-12. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ a b c d e Zathey (1972, p. 39)

- ^ Kopernik, Mikołaj. "Karta "b" recto w: De revolutionibus" (in Latin). Archived from the original on 1997-05-21. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Kopernik, Mikołaj. "Karta dodatkowa "b" verso w: De revolutionibus" (in Latin). Archived from the original on 1997-05-21. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Kopernik, Mikołaj. "Karta dodatkowa "c" recto w: De revolutionibus" (in Latin). Archived from the original on 1997-05-21. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Zathey (1972, p. 3)

- ^ a b c d e f g Zathey (1972, p. 6)

- ^ a b c d e f g Zathey (1972, p. 4)

- ^ Briquet (1907, p. 680)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Zathey (1972, p. 5)

- ^ a b Briquet (1907, p. 558)

- ^ Briquet (1907, p. 467)

- ^ Briquet, Charles M. "Briquet Online - Briquet 8698" (in French). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ^ Briquet (1907, p. 578)

- ^ a b c d Zathey (1972, p. 37)

- ^ Zathey (1972, pp. 7–12)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zathey (1972, p. 12)

- ^ Zathey (1972, p. 13)

- ^ Zathey (1972, p. 15)

- ^ a b c d Zathey (1972, p. 17)

- ^ a b c d e f Zathey (1972, p. 18)

- ^ a b c Zathey (1972, p. 19)

- ^ a b c Zathey (1972, p. 26)

- ^ a b c d e Dorociński (1972, p. 68)

- ^ a b c d e Zathey (1972, p. 24)

- ^ a b c d e f Zathey (1972, p. 25)

- ^ Zathey (1972, p. 27)

- ^ a b c d e f g Zathey (1972, p. 28)

- ^ Briquet (1907, p. 473)

- ^ Briquet (1907, p. 117)

- ^ Zathey (1972, p. 29)

- ^ Dorociński (1972, p. 31)

- ^ a b c d Dorociński (1972, p. 33)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zathey (1972, p. 34)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zathey (1972, p. 35)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zathey (1972, p. 36)

- ^ a b c Gingerich (2004, p. 47)

- ^ a b c d "Poland- Nicolaus Copernicus's masterpiece "De revolutionibus libri sex." (ca 1520)". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

In 1956 the government of Czechoslovakia gave it to the government of the Polish Peoples' Republic.

- ^ "Przepisy porządkowe dla korzystających z czytelni rękopisów" (PDF) (in Polish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ^ a b Bik, Katarzyna. "Okazja raz na wiele lat... Skarby Jagiellonki na wystawie". krakow.wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ a b c Zathey (1972, p. 1)

- ^ Zathey (1972, p. vii)

- ^ Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußische Staatsbibliothek. "Katalog Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin". lbssbb.gbv.de (in German). Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Katalog Biblioteki Narodowej". Biblioteka Narodowa (in Polish). Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ^ Kopernik, Mikołaj. "Autograf: De revolutionibus". Neurosoft Sp. z o.o. (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2013-09-13. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "Polski Komitet ds Unesco: Pamięć Świata". www.unesco.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Nicolaus Copernicus treatise "De revolutionibus libri sex", ca. 1520.: UNESCO-CI". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

Bibliography edit

Studies edit

- Briquet, Charles M. (1907). Les Filigranes (in French). Paris. Archived from the original on 2018-06-30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zathey, J. (1972). "M. Kopernik". In Czartoryski, Paweł (ed.). Rękopis dzieła Mikołaja Kopernika. O obrotach: facsimile. Dzieła wszystkie/Mikołaj Kopernik (in Polish) (1 ed.). Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Dorociński, J. (1972). "M. Kopernik". In Czartoryski, Paweł (ed.). Rękopis dzieła Mikołaja Kopernika. O obrotach: facsimile. Dzieła wszystkie/Mikołaj Kopernik (in Polish) (1 ed.). Kraków: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Gingerich, Owen (2004). Książka, której nikt nie przeczytał (in Polish). Translated by Włodarczyk, J. Warsaw: Amber. ISBN 83-241-1783-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hart, Michael H. (1996). 100 postaci, które miały największy wpływ na dzieje ludzkości (in Polish). Warsaw: Świat Książki. ISBN 83-7129-028-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links edit

- Kopernik, Mikołaj. "Autograf De revolutionibus" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2005-04-10.