The Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement was a joint effort between Ethiopia and the United Kingdom at reestablishing Ethiopian independent statehood following the ousting of Italian troops by combined British and Ethiopian forces in 1941 during the Second World War.

There was a prior Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement signed in 1897. This convention involved Menelik II and it largely dealt with the boundary between Hararghe (Ethiopia) and British Somaliland.

Under the agreement

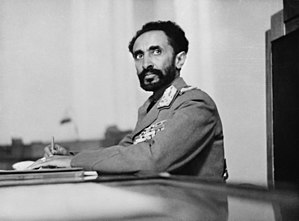

editAfter the return of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie to the throne, an interim Anglo-Ethiopian agreement was signed 31 January 1942 between the two governments; Major General Sir Philip Euen Mitchell, Chief Political Officer of the East African British Forces High Command signed on behalf of the United Kingdom.[1] Britain sent civil advisers to assist Selassie with administrative duties and also provide him with military advisors to maintain internal security and to improve and modernize the Ethiopian army. The terms of this agreement confirmed Ethiopia's status as a sovereign state, although the Ogaden region, the border regions with French Somaliland (known as the "Reserved Areas" or Haud ), the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad, and the Haud, would remain temporarily under British control. The British also assumed control over currency and foreign exchange as well as imports and exports.[2] Whilst it reconfirmed aspects of the Tripartite Agreement of 1906 and the Klobukowski Agreement of 1908, it also took steps to reverse, for example, the immunity the 1908 agreement afforded to all foreigners from Ethiopian laws, albeit whilst stipulating that the trial of any case brought against a foreigner be presided over by a British judge.[3] Lastly, the agreement contained a clause which permitted the Ethiopians to end the agreement by giving three-months' notice.

The Ethiopians soon found the implementation of this agreement intolerable, although they found it a slight improvement over the prior relationship, in which Ethiopia was treated as an occupied enemy nation. Haile Selassie described one aspect of the prior relationship, "they took all the military equipment captured in Our country... openly and boldly saying that it should not be left for the service of blacks."[4] Another point of contention was British control of Ethiopia's banking and finance, which required all letters of credit to be opened in Aden and required all exports to be cleared through that port, yielding an official profit margin of 9-11%; in addition, all dollars earned by exports to the United States were required to be automatically converted to the pound sterling.[5] The Emperor and his ministers soon began to direct their efforts to three specific points: a new treaty to replace this one; a new currency to replace the East African Shilling which had been imposed on Ethiopia as part of the agreement; and a source for military aid which would ensure Ethiopia would no longer depend on the British.[6]

A British-trained police force eventually replaced the former police who were in the service of local provincial governors. There were two revolts during this time: the Woyane rebellion in eastern Tigray Province, which was suppressed with the assistance of British air support; and the other in the Ogaden which was put down by two battalions of Ethiopian forces.[2]

British Ogaden

editBritish Military Administration in Ogaden and Haud | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1955 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||

| Capital | Kebri Dahar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Somali | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II • Cold War | ||||||||

| March 1941 | |||||||||

• Ogaden relinquished | 23 September 1948 | ||||||||

• Haud relinquished | 28 February 1955 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Ethiopia | ||||||||

The British Military Administration in Ogaden, or simply British Ogaden, was the period of British Military Administration from 1941 until 1955. The British came to control Ogaden, and later only Haud, in the aftermath of the East African Campaign in 1941.[7] The British intention was to unite British Ogaden with their colony in Somaliland and the former Italian colony of Somaliland, creating a single polity. This policy was in particular voiced by British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin. However, during the British administration period Haile Selassie had made several territorial demands, and while his demands for the annexation of former Italian Somaliland might have been a bargaining tactic, he was serious about the return of Ethiopian territories in the Ogaden and the annexation of Eritrea. These requests were ignored by the British, who favoured a separate Eritrean entity, and a Greater Somalia. However, after continued Ethiopian deliberations and pressure from the United States, this policy was abandoned.[8][9][10]

The process of reversing the effects of World War II on Ethiopia did not completely end until 1955, when Ethiopia was restored to its internationally recognised borders of 1935, from before the Italian invasion. The British ceded Ogaden to Ethiopia in 1948, with the remaining British control over Haud being relinquished in 1955.[11] After the decision to cede Ogaden to Ethiopia became public there were numerous calls, as well as violent insurgencies, intended to reverse this decision. The movement to gain self-determination from Addis Ababa has continued into the 21st century.[12]

Negotiating a new agreement

editDespite Ethiopian distaste for the agreement, both the Emperor and his innermost group of ministers were reluctant to actually submit the notice required to end the agreement. A set of proposals for a new agreement submitted to the British at the beginning of 1944 was summarily rejected. As John Spencer, an American advisor to Ethiopia in international law during this period, explains, "They feared retaliation in the form of a re-occupation of the province of Tigré, south of Eritrea, and of Sidamo and Gemu Gofa bordering on Kenya, and just possibly other areas in the west such as the provinces of Wollega and Illubabor. These fears were the subject of endless discussions with me."[13] In the end, Ethiopian officials overcame their trepidation and had the three-month notice of termination delivered to the British chargé d'affaires 25 May 1944 along with a request for the prompt negotiations of a new agreement. By this time, the United States had not only re-established its diplomatic mission in Ethiopia, but declared the country eligible for Lend-Lease, providing a vital boost to Ethiopian officials in their negotiation with the United Kingdom.[14]

The initial British response was silence. Only after the Ethiopian government reminded them of the expiry of the agreement 16 August and that they were looking forward receiving possession of the railway and administration of the Haud and Reserved Area, did the British respond. Initially the British attempted to delay the termination of the agreement, claiming it could not accommodate the Ethiopian demands, and settled for a two-month extension for the date to hand the properties over. A negotiating team led by the Earl de la Warr arrived 26 September, and over the following months both sides argued until 19 December 1944, when a new Anglo-Ethiopian agreement was signed and Britain agreed to relinquish several advantages they had enjoyed in Ethiopia.[15] Specifically Britain would remove her garrisons, except from the Ogaden; open Ethiopia's airfields (heretofore restricted to British traffic) to all Allied aircraft; and give up direct control of the Ethiopian section of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad.[16] The new agreement also revoked British precedence over other foreign representatives.[17] However, perhaps more important was the usage of the word "ally" in the agreement. Not only did this remove any further basis for considering Ethiopia "enemy territory"—as General Mitchell had claimed—but it also prevented the possibility Ethiopia from being denied a seat at the future peace conference, which happened in 1947.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Haile Selassie, My Life and Ethiopia's Progress Volume Two: Addis Abebe 1966 E.C. (Chicago: Frontline Distribution, 1999), p. 176

- ^ a b "Ethiopia: Ethiopia in World War II", Library of Congress website (accessed 30 January 2011)

- ^ Fanta, Esubalew Belay (2016). "The British on the Ethiopian Bench: 1942–1944". Northeast African Studies. 16 (2): 67–96. doi:10.14321/nortafristud.16.2.0067. ISSN 0740-9133.

- ^ Haile Selassie, My Life and Ethiopia's Progress, p. 173

- ^ John Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay: A personal account of the Haile Selassie years (Algonac: Reference Publications, 1984), p. 106

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 102; Mauri A., "The re-establishment of the national monetary and banking system in Ethiopia", The South African Journal of Economic History, Vol. 24, n. 2, p. 91

- ^ Super powers in the Horn of Africa - Page 48, 1987, Madan Sauldie

- ^ Cahiers d'études africaines - Volume 2 - Page 65

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 142

- ^ Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: O-X - Page 1026, Siegbert Uhlig - 2010

- ^ a b Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 152

- ^ Vaughan, Sarah. "Ethiopia, Somalia, and the Ogaden: Still a Running Sore at the Heart of the Horn of Africa." Secessionism in African Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019. 91-123.

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 143

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, p. 144

- ^ Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay, pp. 145-153

- ^ "The Negus Negotiates", Time 1 January 1945 (accessed 14 May 2009)

- ^ Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), p. 180

Further reading

edit- "Consequences of the British Occupation of Ethiopia During World II" by Theodore M. Vestal

- Harold Courlander, "The Emperor Wore Clothes: Visiting Haile Sellassie in 1943", American Scholar, 58 (1959), pp. 277ff.

- Arnaldo Mauri, "The re-establishment of the national monetary and banking system in Ethiopia, 1941-1963", The South African Journal of Economic History, Vol. 24, n. 2, 2009, pp. 82–130.