The Tibet Autonomous Region, officially the Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang,[note 1] is an autonomous region of China and is part of Southwestern China.

Tibet Autonomous Region | |

|---|---|

| Chinese transcription(s) | |

| • Simplified Chinese | 西藏自治区 |

| • Hanyu pinyin | Xīzàng Zìzhìqū |

| • Abbreviation | XZ / 藏 (Zàng) |

| Tibetan transcription(s) | |

| • Tibetan script | བོད་རང་སྐྱོང་ལྗོངས། |

| • Tibetan pinyin | Poi Ranggyong Jong |

| • Wylie translit. | bod rang skyong ljongs |

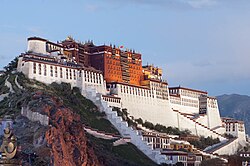

The Potala Palace in Lhasa | |

Location of the Tibet Autonomous Region in China (territory claimed by China but controlled by India is striped) | |

| Country | China |

| Capital and largest city | Lhasa |

| Divisions - Prefecture-level - County-level - Township- level | 7 prefectures 74 counties 699 towns and subdistricts |

| Government | |

| • Type | Autonomous region |

| • Body | Tibet Autonomous Region People's Congress |

| • Party Secretary | Wang Junzheng |

| • Congress Chairman | Losang Jamcan |

| • Government Chairman | Yan Jinhai |

| • Regional CPPCC Chairman | Pagbalha Geleg Namgyai |

| • National People's Congress Representation | 24 deputies |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,228,400 km2 (474,300 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| Highest elevation | 8,848 m (29,029 ft) |

| Population (2020[2]) | |

| • Total | 3,648,100 |

| • Rank | 32nd |

| • Density | 3.0/km2 (7.7/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 33rd |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition | 86.0% Tibetan 12.2% Han 0.8% others |

| • Languages and dialects | Tibetan, Mandarin Chinese |

| GDP (2023)[3] | |

| • Total | CN¥ 239,267 million (31th)

US$ 33,954 million |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 65,642 (22th)

US$ 9,315 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-XZ |

| HDI (2022) | 0.648[4] (31st) – medium |

| Website | www |

It was formally established in 1965 to replace the Tibet Area, the former administrative division of the PRC established after the annexation of Tibet. The establishment was about five years after the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the dismissal of the Kashag, and about 13 years after the original annexation.

The current borders of the Tibet Autonomous Region were generally established in the 18th century[6] and include about half of historical Tibet. The Tibet Autonomous Region spans over 1,200,000 km2 (460,000 sq mi), and is the second-largest province-level division of China by area, after Xinjiang. Due to its harsh and rugged terrain, it is sparsely populated at just over 3.6 million people with a population density of 3 inhabitants per square kilometre (7.8/sq mi), and is the least-populous autonomous region or province in China.

History

editYarlung kings founded the Tibetan Empire in 618. By the end of the 8th century, the empire reached its greatest extent. After a civil war, the empire broke up in 842. The royal lineage fragmented and ruled over small kingdoms such as Guge and Maryul. The Mongol Empire conquered Tibet in 1244 but granted the region a degree of political autonomy. Kublai Khan later incorporated Tibetans into his Yuan empire (1271–1368). The Sakya lama Drogön Chögyal Phagpa became religious teacher to Kublai in the 1250s, and was made the head of the Tibetan region administration c. 1264.

From 1354 to 1642, Central Tibet (Ü-Tsang) was ruled by a succession of dynasties from Nêdong, Shigatse and Lhasa. In 1642, the Ganden Phodrang court of the 5th Dalai Lama was established by Güshi Khan of the Khoshut Khanate, who was enthroned as King of Tibet. The Khoshuts ruled until 1717, when they were overthrown by the Dzungar Khanate. Despite politically charged historical debate concerning the nature of Sino-Tibetan relations,[7][8][9] some historians[who?] posit that Tibet under the Ganden Phodrang (1642–1951) was an independent state, albeit under various foreign suzerainties for much of this period, including by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The Dzungar forces were in turn expelled by the 1720 expedition to Tibet during the Dzungar–Qing Wars. This began a period of direct Qing rule over Tibet.[10]

From the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912 until 1950, the State of Tibet was de facto independent, as were other regions claimed by the successor Republic of China. The Republican regime, preoccupied with warlordism (1916–1928), civil war (1927–1949) and Japanese invasion (1937–1945), did not exert authority in Tibet. Other regions of ethno-cultural Tibet in eastern Kham and Amdo had been under de jure administration of the Chinese dynastic government since the mid-18th century;[11] they form parts of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan.

In 1950, following the proclamation of the People's Republic of China the year before, the People's Liberation Army entered Tibet and defeated the Tibetan army in a battle fought near the city of Chamdo. In 1951, Tibetan representatives signed the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet with the Central People's Government affirming China's sovereignty over Tibet and the annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China. The 14th Dalai Lama ratified the agreement in October 1951.[12][13][14] After the failure of a violent uprising in 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India and renounced the Seventeen Point Agreement. During the 1950s and 1960s, Western-dispatched insurgents were parachuted into Tibet, almost all of whom were captured and killed.[15]: 238 The establishment of the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1965 made Tibet a provincial-level division of China.

Geography

editThe Tibet Autonomous Region is located on the Tibetan Plateau, the highest region on Earth. In northern Tibet elevations reach an average of over 4,572 metres (15,000 ft). Mount Everest is located on Tibet's border with Nepal.

China's provincial-level areas of Xinjiang, Qinghai and Sichuan lie to the north, northeast and east, respectively, of the Tibet AR. There is also a short border with Yunnan Province to the southeast. The countries to the south and southwest are Myanmar, India, Bhutan, and Nepal. China claims Arunachal Pradesh administered by India as part of the Tibet Autonomous Region. It also claims some areas adjoining the Chumbi Valley that are recognised as Bhutan's territory, and some areas of eastern Ladakh claimed by India. India and China agreed to respect the Line of Actual Control in a bilateral agreement signed on 7 September 1993.[16][non-primary source needed]

Physically, the Tibet AR may be divided into two parts: the lakes region in the west and north-west and the river region, which spreads out on three sides of the former on the east, south and west. Both regions receive limited amounts of rainfall as they lie in the rain shadow of the Himalayas; however, the region names are useful in contrasting their hydrological structures, and also in contrasting their different cultural uses: nomadic in the lake region and agricultural in the river region.[17] On the south the Tibet AR is bounded by the Himalayas, and on the north by a broad mountain system. The system at no point narrows to a single range; generally there are three or four across its breadth. As a whole the system forms the watershed between rivers flowing to the Indian Ocean — the Indus, Brahmaputra and Salween and its tributaries — and the streams flowing into the undrained salt lakes to the north.

The lake region extends from the Pangong Tso Lake in Ladakh, Lake Rakshastal, Yamdrok Lake and Lake Manasarovar near the source of the Indus River, to the sources of the Salween, the Mekong and the Yangtze. Other lakes include Dagze Co, Namtso, and Pagsum Co. The lake region is a wind-swept Alpine grassland. This region is called the Chang Tang (Byang sang) or 'Northern Plateau' by the people of Tibet. It is 1,100 km (680 mi) broad and covers an area about equal to that of France. Due to its great distance from the ocean it is extremely arid and possesses no river outlet. The mountain ranges are spread out, rounded, disconnected, and separated by relatively flat valleys.

The Tibet AR is dotted over with large and small lakes, generally salt or alkaline, and intersected by streams. Due to the presence of discontinuous permafrost over the Chang Tang, the soil is boggy and covered with tussocks of grass, thus resembling the Siberian tundra. Salt and fresh-water lakes are intermingled. The lakes are generally without outlet, or have only a small effluent. The deposits consist of soda, potash, borax and common salt. The lake region is noted for a vast number of hot springs, which are widely distributed between the Himalaya and 34° N, but are most numerous to the west of Tengri Nor (north-west of Lhasa). So intense is the cold in this part of Tibet that these springs are sometimes represented by columns of ice, the nearly boiling water having frozen in the act of ejection.

The river region is characterized by fertile mountain valleys and includes the Yarlung Tsangpo River (the upper courses of the Brahmaputra) and its major tributary, the Nyang River, the Salween, the Yangtze, the Mekong, and the Yellow River. The Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon, formed by a horseshoe bend in the river where it flows around Namcha Barwa, is the deepest and possibly longest canyon in the world.[18] Among the mountains there are many narrow valleys. The valleys of Lhasa, Xigazê, Gyantse and the Brahmaputra are free from permafrost, covered with good soil and groves of trees, well irrigated, and richly cultivated.

The South Tibet Valley is formed by the Yarlung Tsangpo River during its middle reaches, where it travels from west to east. The valley is approximately 1,200 km (750 mi) long and 300 km (190 mi) wide. The valley descends from 4,500 m (14,760 ft) above sea level to 2,800 m (9,190 ft). The mountains on either side of the valley are usually around 5,000 m (16,400 ft) high.[19][20] Lakes here include Lake Paiku and Lake Puma Yumco.

Government

editThe Tibet Autonomous Region is a province-level entity of the People's Republic of China. Chinese law nominally guarantees some autonomy in the areas of education and language policy. Like other subdivisions of China, routine administration is carried out by a People's Government, headed by a chairman, who has been an ethnic Tibetan except for an interregnum during the Cultural Revolution. As with other Chinese provinces, the chairman carries out work under the direction of the regional secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. The standing committee of the regional Communist Party Committee serves as the top rung of political power in the region. The current chairman is Yan Jinhai and the current party secretary is Wang Junzheng.

Administrative divisions

editThe Autonomous Region is divided into seven prefecture-level divisions: six prefecture-level cities and one prefecture.

These in turn are subdivided into a total of 66 counties and 8 districts (Chengguan, Doilungdêqên, Dagzê, Samzhubzê, Karub, Bayi, Nêdong, and Seni).

| Administrative divisions of Tibet Autonomous Region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

☐ Areas disputed with India or Bhutan (see Sino-Indian border dispute and Bhutanese enclaves)

| ||||||||

| Division code[21] | Division | Area in km2[22] | Population 2020[23] | Seat | Divisions[24] | |||

| Districts | Counties | CL cities | ||||||

| 540000 | Tibet Autonomous Region | 1,228,400.00 | 3,648,100 | Lhasa city | 8 | 64 | 2 | |

| 540100 | Lhasa city | 29,538.90 | 867,891 | Chengguan District | 3 | 5 | ||

| 540200 | Shigatse / Xigazê city | 182,066.26 | 798,153 | Samzhubzê District | 1 | 17 | ||

| 540300 | Chamdo / Qamdo city | 108,872.30 | 760,966 | Karuo District | 1 | 10 | ||

| 540400 | Nyingchi city | 113,964.79 | 238,936 | Bayi District | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| 540500 | Shannan / Lhoka city | 79,287.84 | 354,035 | Nêdong District | 1 | 10 | 1 | |

| 540600 | Nagqu city | 391,816.63 | 504,838 | Seni District | 1 | 10 | ||

| 542500 | Ngari Prefecture | 296,822.62 | 123,281 | Gar County | 7 | |||

| Administrative divisions in Tibetan, Chinese, and varieties of romanizations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Tibetan | Tibetan Pinyin | Wylie transliteration | Chinese | Pinyin |

| Tibet Autonomous Region | བོད་རང་སྐྱོང་ལྗོངས། | Poi Ranggyongjong | bod rang skyong ljongs | 西藏自治区 | Xīzàng Zìzhìqū |

| Lhasa city | ལྷ་ས་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | Lhasa Chongkyir | lha sa grong khyer | 拉萨市 | Lāsà Shì |

| Xigazê city | གཞིས་ཀ་རྩེ་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | Xigazê Chongkyir | ggzhis ka rtse grong khyer | 日喀则市 | Rìkāzé Shì |

| Qamdo city | ཆབ་མདོ་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | Qamdo Chongkyir | chab mdo grong khyer | 昌都市 | Chāngdū Shì |

| Nyingchi city | ཉིང་ཁྲི་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | Nyingchi Chongkyir | nying khri grong khyer | 林芝市 | Línzhī Shì |

| Shannan city | ལྷོ་ཁ་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | Lhoka Chongkyir | lho kha grong khyer | 山南市 | Shānnán Shì |

| Nagqu city | ནག་ཆུ་གྲོང་ཁྱེར། | Nagqu Chongkyir | nag chu grong khyer | 那曲市 | Nàqū Shì |

| Ngari Prefecture | མངའ་རིས་ས་ཁུལ། | Ngari Sakü | mnga' ris sa khul | 阿里地区 | Ālǐ Dìqū |

Urban areas

edit| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Cities | 2020 Urban area[25] | 2010 Urban area[26] | 2020 City proper |

| 1 | Lhasa | 551,802 | 199,159[a] | 867,891 |

| 2 | Xigazê | 94,464 | 63,967[b] | 798,153 |

| 3 | Nyingchi | 60,696 | [c] | 238,936 |

| 4 | Shannan | 54,188 | [d] | 354,035 |

| 5 | Qamdo | 50,127 | [e] | 760,966 |

| 6 | Nagqu | 31,436 | [f] | 504,838 |

| (7) | Mainling | 5,915[g] | see Nyingchi | |

| (8) | Cona | 2,871[h] | see Shannan | |

- ^ New districts established after census: Doilungdêqên (Doilungdêqên County), Dagzê (Dagzê County). These new districts not included in the urban area & district area count of the pre-expanded city.

- ^ Xigazê Prefecture is currently known as Xigazê PLC after census; Xigazê CLC is currently known as Samzhubzê after 2010 census.

- ^ NyingchiPrefecture is currently known as Nyingchi PLC after census; Nyingchi County is currently known as Bayi after 2010 census.

- ^ Shannan Prefecture is currently known as Shannan PLC after census; Nêdong County is currently known as Nêdong after census.

- ^ Qamdo Prefecture is currently known as Qamdo PLC after census; Qamdo County is currently known as Karuo after census.

- ^ Nagqu Prefecture is currently known as Nagqu PLC after census; Nagqu County is currently known as Seni after 2010 census.

- ^ Mainling County is currently known as Mainling CLC after 2020 census.

- ^ Cona County is currently known as Cona CLC after 2020 census.

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912[27] | 1,160,000 | — |

| 1928[28] | 372,000 | −67.9% |

| 1936–37[29] | 372,000 | +0.0% |

| 1947[30] | 1,000,000 | +168.8% |

| 1954[31] | 1,273,969 | +27.4% |

| 1964[32] | 1,251,225 | −1.8% |

| 1982[33] | 1,892,393 | +51.2% |

| 1990[34] | 2,196,010 | +16.0% |

| 2000[35] | 2,616,329 | +19.1% |

| 2010[36] | 3,002,166 | +14.7% |

| 2020[37] | 3,648,100 | +21.5% |

| Xikang Province / Chuanbian SAR was established in 1923 from parts of Tibet / Lifan Yuan; dissolved in 1955 and parts were incorporated into Tibet AR. | ||

With an average of only two people per square kilometer, Tibet has the lowest population density among any of the Chinese province-level administrative regions, mostly due to its harsh and rugged terrain.[38] In 2022, only 37.4 percent of Tibet's population was urban, with 63.4 being rural, amongst the lowest in China, though this is significantly up from 22.6 percent in 2011.[3]

In 2020 the Tibetan population was three million.[39] The ethnic Tibetans, comprising 86.0% of the population,[39] mainly adhere to Tibetan Buddhism and Bön, although there is an ethnic Tibetan Muslim community.[40] Other Muslim ethnic groups such as the Hui and the Salar have inhabited the region. There is also a tiny Tibetan Christian community in eastern Tibet. Smaller tribal groups such as the Monpa and Lhoba, who follow a combination of Tibetan Buddhism and spirit worship, are found mainly in the southeastern parts of the region.

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic Tibetans. According to tradition the original ancestors of the Tibetan people, as represented by the six red bands in the Tibetan flag, are: the Se, Mu, Dong, Tong, Dru and Ra. Other traditional ethnic groups with significant population or with the majority of the ethnic group reside in Tibet include Bai people, Blang, Bonan, Dongxiang, Han, Hui people, Lhoba, Lisu people, Miao, Mongols, Monguor (Tu people), Menba (Monpa), Mosuo, Nakhi, Qiang, Nu people, Pumi, Salar, and Yi people.

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition published between 1910 and 1911, the total population of the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, including the lamas in the city and vicinity, was about 30,000, and the permanent population also included Chinese families (about 2,000).[41]

Most Han people in the Tibet Autonomous Region (12.2% of the total population)[39] are recent migrants, because all of the Han were expelled from "Outer Tibet" (Central Tibet) following the British invasion until the establishment of the PRC.[42] Only 8% of Han people have household registration in TAR, others keep their household registration in place of origin.[43]

Tibetan scholars and exiles claim that, with the 2006 completion of the Qingzang Railway connecting the Tibet Autonomous Region to Qinghai Province, there has been an "acceleration" of Han migration into the region.[44] The Tibetan government-in-exile based in northern India asserts that the PRC is promoting the migration of Han workers and soldiers to Tibet to marginalize and assimilate the locals.[45]

Religion

editThe main religion in Tibet has been Buddhism since its outspread in the 8th century AD. Before the arrival of Buddhism, the main religion among Tibetans was an indigenous shamanic and animistic religion, Bon, which now comprises a sizeable minority and influenced the formation of Tibetan Buddhism.

According to estimates from the International Religious Freedom Report of 2012, most Tibetans (who comprise 91% of the population of the Tibet Autonomous Region) are adherents of Tibetan Buddhism, while a minority of 400,000 people are followers the native Bon or folk religions which share the image of Confucius (Tibetan: Kongtse Trulgyi Gyalpo) with Chinese folk religion, though in a different light.[48][49] According to some reports, the government of China has been promoting the Bon religion, linking it with Confucianism.[50]

Most of the Han Chinese who reside in Tibet practice their native Chinese folk religion (神道; shén dào; 'Way of the Gods'). There is a Guandi Temple of Lhasa (拉萨关帝庙) where the Chinese god of war Guandi is identified with the cross-ethnic Chinese, Tibetan, Mongol and Manchu deity Gesar. The temple is built according to both Chinese and Tibetan architecture. It was first erected in 1792 under the Qing dynasty and renovated around 2013 after decades of disrepair.[51][52]

Built or rebuilt between 2014 and 2015 is the Guandi Temple of Qomolangma (Mount Everest), on Ganggar Mount, in Tingri County.[53][54]

There are four mosques in the Tibet Autonomous Region with approximately 4,000 to 5,000 Muslim adherents,[46] although a 2010 Chinese survey found a higher proportion of 0.4%.[47] There is a Catholic church with 700 parishioners, which is located in the traditionally Catholic community of Yanjing in the east of the region.[46]

Human rights

editFrom the 1951 Seventeen Point Agreement to 2003, life expectancy in Tibet increased from thirty-six years to sixty-seven years with infant mortality and absolute poverty declining steadily.[55] The average life expectancy in Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) reached 72.19 years by 2021, compared to 35.5 years recorded in 1951,[56] the death rate of women in childbirth dropped to 38.63 per 100,000 in 2023 from 5,000 per 100,000 in 1951, the infant mortality rate fell to 5.37 per 1,000 from 430 per 1,000.[57]

Before the annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China in 1951, Tibet was ruled by a theocracy[58] and had a caste-like social hierarchy.[59] Human rights in Tibet prior to its incorporation into the People's Republic of China differed considerably from those in the modern era. Due to tight control of press in mainland China, including the Tibet Autonomous Region,[60] it is difficult to accurately determine the scope of human rights abuses.[61]

When General Secretary Hu Yaobang visited Tibet in 1980 and 1982, he disagreed with what he viewed as heavy-handedness.[15]: 240 Hu reduced the number of Han party cadre, and relaxed social controls.[15]: 240

Critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) say the CCP's official aim to eliminate "the three evils of separatism, terrorism and religious extremism" is used as a pretext for human rights abuses.[62] A 1992 Amnesty International report stated that judicial standards in the Tibet Autonomous Region were not up to "international standards". The report charged the CCP[63] government with keeping political prisoners and prisoners of conscience; ill-treatment of detainees, including torture, and inaction in the face of ill-treatment; the use of the death penalty; extrajudicial executions;[63][64] and forced abortion and sterilization.[65][66][67][68][69]

Towns and villages in Tibet

editComfortable Housing Program

editBeginning in 2006, 280,000 Tibetans who lived in traditional villages and as nomadic herdsmen have been forcefully relocated into villages and towns. In those areas, new housing was built and existing houses were remodelled to serve a total of 2 million people. Those living in substandard housing were required to dismantle their houses and remodel them to government standards. Much of the expense was borne by the residents themselves,[70] often through bank loans. The population transfer program, which was first implemented in Qinghai where 300,000 nomads were resettled, is called "Comfortable Housing", which is part of the "Build a New Socialist Countryside" program. Its effect on Tibetan culture has been criticized by exiles and human rights groups.[70] Finding employment is difficult for relocated persons who have only agrarian skills. Income shortfalls are offset by government support programs.[71] It was announced that in 2011 that 20,000 Communist Party cadres will be placed in the new towns.[70]

Economy

edit| Year | GDP in billions of yuan |

| 1995 | 5.61 |

| 2000 | 11.78 |

| 2005 | 24.88 |

| 2010 | 50.75 |

| 2015 | 102.64 |

| 2021 | 208.18[73] |

| 2022 | 213[74] |

| 2023 | 239.3[75] |

In general, China's minority regions have some of the highest per capita government spending public goods and services.[76]: 366 Providing public goods and services in these areas is part of a government effort to reduce regional inequalities, reduce the risk of separatism, and stimulate economic development.[76]: 366 Tibet has the highest amount of funding from the central government to the local government as of at least 2019.[76]: 370–371 As of at least 2019, Tibet has the highest total per capita government expenditure of any region in China, including the highest per capita government expenditure on health care, the highest per capita government expenditure on education, and the second highest per capita government expenditure on social security and employment.[76]: 367–369

The Tibetans traditionally depended upon agriculture for survival. Since the 1980s, however, other jobs such as taxi-driving and hotel retail work have become available in the wake of Chinese economic reform. In 2011, Tibet's GDP topped 60.5 billion yuan (US$9.60 billion), nearly more than seven times as big as the 11.78 billion yuan (US$1.47 billion) in 2000. Economic growth since the beginning of the 21st century has averaged over 10 percent a year.[38] By 2023, its gross domestic product (GDP) stood at nearly 239.3 billion yuan (about 33.6 billion U.S. dollars), adding that the growth rates of the region's major economic indicators, including per capita disposable income, fixed asset investment, and total retail sales of consumer goods, all ranked first in China. The added value of the service sector accounted for 54.1 percent and contributed a 57.6 percent share to economic growth. Investment in fixed assets also grew rapidly last year, with investment in infrastructure up by 34.8 percent and investment in areas related to people's livelihoods up by 31.8 percent.[77] Its GDP grew by an annual average of 9.5 percent from 2012 to 2023, about 3 percentage points higher than the China’s national average.[78]

By 2022, the GDP of the region surpassed 213 billion yuan (US$31.7 billion in nominal), while GDP per capita reached CN¥58,438 (US$8,688 in nominal).[3] In 2022, Tibet's GDP per capita ranked 25th highest in China, as well as higher than any South Asian country except Maldives.[79] In 2008, Chinese news media reported that the per capita disposable incomes of urban and rural residents in Tibet averaged (CN¥12,482 (US$1,798) and CN¥3,176 (US$457) respectively.[80]

While traditional agriculture and animal husbandry continue to lead the area's economy, in 2005 the tertiary sector contributed more than half of its GDP growth, the first time it surpassed the area's primary industry.[81][82] Rich reserves of natural resources and raw materials have yet to lead to the creation of a strong secondary sector, due in large part to the province's inhospitable terrain, low population density, an underdeveloped infrastructure and the high cost of extraction.[38]

The collection of caterpillar fungus (Cordyceps sinensis, known in Tibetan as Yartsa Gunbu) in late spring / early summer is in many areas the most important source of cash for rural households. It contributes an average of 40% to rural cash income and 8.5% to the Tibet Autonomous Region's GDP.[83]

The re-opening of the Nathu La pass (on southern Tibet's border with India) should facilitate Sino-Indian border trade and boost Tibet's economy.[84]

The China Western Development policy was adopted in 2000 by the central government to boost economic development in western China, including the Tibet Autonomous Region.[76]: 133 Because the central government permits Tibet to have a preferentially low corporate income tax rate, many corporations have registered in Tibet.[76]: 146

Education

editThere are 4 universities and 3 special colleges in Tibet,[85] including Tibet University, Tibet University for Nationalities, Tibet Tibetan Medical University, Tibet Agricultural and Animal Husbandry College, Lhasa Teachers College, Tibet Police College and Tibet Vocational and Technical College.

As of at least 2019, Tibet is the region of China with the largest per capita government spending on education.[76]: 367–369

Tourism

editForeign tourists were first permitted to visit the Tibet Autonomous Region in the 1980s. While the main attraction is the Potala Palace in Lhasa, there are many other popular tourist destinations including the Jokhang Temple, Namtso Lake, and Tashilhunpo Monastery.[86] Nonetheless, tourism in Tibet is still restricted for non-Chinese passport holders (including citizens of the Republic of China from Taiwan), and foreigners must apply for a Tibet Entry Permit to enter the region.

Transportation

editA 2019 white paper from The State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China reported Tibet's road system has achieved a total of 118,800 km.[87]

Airports

editThe civil airports in Tibet are Lhasa Gonggar Airport,[88] Qamdo Bangda Airport, Nyingchi Airport, and the Gunsa Airport.

Gunsa Airport in Ngari Prefecture began operations on 1 July 2010, to become the fourth civil airport in China's Tibet Autonomous Region.[89]

The Peace Airport for Xigazê was opened for civilian use on 30 October 2010.[90]

Announced in 2010, Nagqu Dagring Airport was expected to become the world's highest altitude airport, at 4,436 meters above sea level.[91] However, in 2015 it was reported that construction of the airport has been delayed due to the necessity to develop higher technological standards.[92]

Railway

editThe Qinghai–Tibet Railway from Golmud to Lhasa was completed on 12 October 2005. It opened to regular trial service on 1 July 2006. Five pairs of passenger trains run between Golmud and Lhasa, with connections onward to Beijing, Chengdu, Chongqing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Xining and Lanzhou. The line includes the Tanggula Pass, which, at 5,072 m (16,640 ft) above sea level, is the world's highest railway.

The Lhasa–Xigazê Railway branch from Lhasa to Xigazê was completed in 2014. It opened to regular service on 15 August 2014. The planned China–Nepal railway will connect Xigazê to Kathmandu, capital of Nepal, and is expected to be completed around 2027.[93]

The construction of the Sichuan–Tibet Railway began in 2015. The line is expected to be completed around 2025.[94]

See also

edit- China Tibetology Research Center

- Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China

- History of Tibet (1950–present)

- Kazara

- List of prisons in the Tibet Autonomous Region

- List of universities and colleges in Tibet

- Tibet Area (administrative division)

- Tibetan independence movement

- Sinicization of Tibet

- Shigatse Photovoltaic Power Plant

Notes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ 西藏概况(2007年) [Overview of Tibet (2007)] (in Chinese). People's Government of Tibet Autonomous Region. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 3)". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "National Data". China NBS. March 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024. see also "zh: 2023年西藏自治区国民经济和社会发展统计公报". xizang.gov.cn. 9 May 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024. The average exchange rate of 2023 was CNY 7.0467 to 1 USD dollar "Statistical communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2023 national economic and social development" (Press release). China NBS. 29 February 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Indices (8.0)- China". Global Data Lab. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han (5 January 2024). "China Doesn't Want You to Say 'Tibet' Anymore". Wall Street Journal. New York City. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "What is Tibet? – Fact and Fancy", Excerpt from Goldstein, Melvyn, C. (1994). Change, Conflict and Continuity among a Community of Nomadic Pastoralist: A Case Study from Western Tibet, 1950–1990. pp. 76–87.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wylie, Turrell V. (2003), "Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty", in McKay, Alex (ed.), The History of Tibet: Volume 2, The Medieval Period: c. AD 850–1895, the Development of Buddhist Paramountcy, New York: Routledge, p. 470, ISBN 978-0-415-30843-4.

- ^ Wang, Jiawei; Nyima, Gyaincain (1997), The Historical Status of China's Tibet, Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, pp. 1–40, ISBN 978-7-80113-304-5.

- ^ Laird (2006), pp. 106–107

- ^

Huaiyin Li (13 August 2019). The Making of the Modern Chinese State: 1600–1950. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9780429777899. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

[...] in 1720 through two military expeditions, the Qing put Tibet under its direct control by stationing a permanent garrison in Lhasa and appointing an Imperial Commissioner in Tibet to supervise the newly organized government [...]

- ^ Grunfeld, A. Tom, The Making of Modern Tibet, M.E. Sharpe, p. 245.

- ^ Gyatso, Tenzin, Dalai Lama XIV, interview, 25 July 1981.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951, University of California Press, 1989, p. 812–813.

- ^ A. Tom Grunfeld (30 July 1996). The Making of Modern Tibet. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-0-7656-3455-9.

- ^ a b c Lampton, David M. (2024). Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-8725-8.

- ^ "Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas | UN Peacemaker". peacemaker.un.org. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Tibet: Agricultural Regions". Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ "The World's Biggest Canyon". china.org. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ^ Yang, Qinye; Zheng, Du (2004). Tibetan Geography. China Intercontinental Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-7-5085-0665-4.

- ^ Zheng Du, Zhang Qingsong, Wu Shaohong: Mountain Geoecology and Sustainable Development of the Tibetan Plateau (Kluwer 2000), ISBN 0-7923-6688-3, p. 312;

- ^ 中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码 (in Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ Shenzhen City Bureau of Statistics. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》 (in Chinese). China Statistics Print. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Census Office of the State Council; Population and Employment Statistics Division of the National Bureau of Statistics, eds. (2012). 中国2010人口普查分乡、镇、街道资料 (1st ed.). Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.

- ^ Ministry of Civil Affairs (August 2014). 《中国民政统计年鉴2014》 (in Chinese). China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-7130-9.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2022). 中国2020年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-9772-9.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- ^ 1912年中国人口. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 1928年中国人口. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 1936–37年中国人口. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 1947年全国人口. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于第一次全国人口调查登记结果的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009.

- ^ 第二次全国人口普查结果的几项主要统计数字. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九八二年人口普查主要数字的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九九〇年人口普查主要数据的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012.

- ^ 现将2000年第五次全国人口普查快速汇总的人口地区分布数据公布如下. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012.

- ^ "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013.

- ^ "FACTBOX-Key takeaways from China's 2020 population census". Reuters. 11 May 2021.

- ^ a b c China Economy @ China Perspective. Thechinaperspective.com. Retrieved on 18 July 2013.

- ^ a b c "How Much Does Beijing Control the Ethnic Makeup of Tibet?". ChinaFile. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Hannue, Dialogues Tibetan Dialogues Han

- ^ Yule, Henry; Waddell, Laurence (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 531.

- ^ Grunfeld, A. Tom (1996). The Making of Modern Tibet. East Gate Books. pp. 114–119.

- ^ 西藏自治区常住人口超过300万. Xizang gov. Xizang gov. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Tim (28 March 2008). "Tibetans see 'Han invasion' as spurring violence | McClatchy". Mcclatchydc.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Population Transfer Programmes". Central Tibetan Administration. 2003. Archived from the original on 30 July 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ a b c Internazional Religious Freedom Report 2012 Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine by the US government. p. 20: «Most ethnic Tibetans practice Tibetan Buddhism, although a sizeable minority practices Bon, an indigenous religion, and very small minorities practice Islam, Catholicism, or Protestantism. Some scholars estimate that there are as many as 400,000 Bon followers across the Tibetan Plateau. Scholars also estimate that there are up to 5,000 ethnic Tibetan Muslims and 700 ethnic Tibetan Catholics in the TAR.»

- ^ a b Min Junqing. The Present Situation and Characteristics of Contemporary Islam in China. JISMOR, 8. 2010 Islam by province, page 29 Archived 27 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Data from: Yang Zongde, Study on Current Muslim Population in China, Jinan Muslim, 2, 2010.

- ^ Te-Ming TSENG; Shen-Yu LIN (December 2007). 《臺灣東亞文明研究學刊》第4卷第2期(總第8期) [The Image of Confucius in Tibetan Culture] (PDF). National Taiwan University. pp. 169–207. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Shenyu Lin. The Tibetan Image of Confucius Archived 13 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines.

- ^ China-Tibet Online: Confucius ruled as a "divine king" in Tibet[permanent dead link]. 4 November 2014

- ^ World Guangong Culture: Lhasa, Tibet: Guandi temple was inaugurated Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ China-Tibet Online: Tibet's largest Guandi Temple gets repaired[permanent dead link]. 13 March 2013

- ^ World Guangong Culture: Dingri, Tibet: Cornerstone Laying Ceremony being Grandly Held for the Reconstruction of Qomolangma Guandi Temple Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ World Guangong Culture: Wuhan, China: Yang Song Meets Cui Yujing to Discuss Qomolangma Guandi Temple Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lin, Chun (2006). The transformation of Chinese socialism. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8223-3785-0. OCLC 63178961.

- ^ Life expectancy at record high in Tibet, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202201/08/WS61d8d11da310cdd39bc7fd4d.html, January 8, 2022.

- ^ Xizang's maternal, infant mortality rates at record low, https://english.news.cn/20240412/6f2d26d6715c423f9ba2b089f6f0ffb6/c.html, April 12, 2024.

- ^ Samten G. Karmay, Religion and Politics: commentary[usurped], September 2008: "from 1642 the Ganden Potrang, the official seat of the government in Drepung Monastery, came to symbolize the supreme power in both the theory and practice of a theocratic government. This was indeed a political triumph that Buddhism had never known in its history in Tibet."

- ^ Fjeld, Heidi (2003). Commoners and Nobles:Hereditary Divisions in Tibet. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 5. ISBN 9788791114175.

- ^ Regions and territories: Tibet bbc http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/country_profiles/4152353.stm Archived 2011-04-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ US State Department, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, 2008 Human Rights Report: China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau), February 25, 2009

- ^ Simon Denyer, China cracks down on aggrieved party cadres in Xinjiang and Tibet Archived 2016-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b Amnesty International, Amnesty International: "China – Amnesty International's concerns in Tibet" Archived 2009-09-12 at the Wayback Machine, Secretary-General's Report: Situation in Tibet, E/CN.4/1992/37

- ^ "Amnesty International Documents". Hrweb.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn; Cynthia, Beall (March 1991). "China's Birth Control Policy in the Tibet Autonomous Region". Asian Survey. 31 (3): 285–303. doi:10.2307/2645246. JSTOR 2645246.

- ^ "Human Rights Violations in Tibet". Human Rights Watch. 13 June 2000.

- ^ "Database of NGO Reports presented to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child" (PDF). Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "China must urgently address rights violations in Tibet – UN senior official". UN News. 2 November 2012.

- ^ "European Parliament resolution of 10 April 2008 on Tibet". Publications Office of the EU. 10 April 2008.

- ^ a b c "They Say We Should Be Grateful". Human Rights Watch. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (27 June 2013). "Rights Report Faults Mass Relocation of Tibetans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ Historical GDP of Provinces "Home – Regional – Annual by Province" (Press release). China NBS. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "2021年西藏GDP达2080.17亿元 同比增长6.7%_中国经济网——国家经济门户". district.ce.cn. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ "National Data". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Tibet's GDP up 9.5 percent in 2023, https://www.macaubusiness.com/tibets-gdp-up-9-5-percent-in-2023/, January 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lin, Shuanglin (2022). China's Public Finance: Reforms, Challenges, and Options. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-09902-8.

- ^ Xizang's GDP up 9.5 percent in 2023. https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202401/23/content_WS65afbd1ac6d0868f4e8e36bf.html, January 23, 2024.

- ^ Tibet's annual GDP growth reaches 9.5% over 10 years. http://english.scio.gov.cn/pressroom/2022-10/08/content_78454461.htm, October 8, 2022.

- ^ International Monetary Fund. "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "Tibetans report income rises". news.nen.com.cn. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Xinhua – Per capita GDP tops $1,000 in Tibet". news.xinhuanet.com. Xinhua. 31 January 2006. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Tibet posts fixed assets investment rise". news.xinhuanet.com. Xinhua. 31 January 2006. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Winkler D. 2008 Yartsa gunbu (Cordyceps sinenis) and the fungal commodification of rural Tibet. Economic Botany 62.3. See also Hannue, Dialogues Tibetan Dialogues Han

- ^ Maseeh Rahman in New Delhi (19 June 2006). "China and India to trade across Himalayas | World news". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "全国高等学校名单 – 中华人民共和国教育部政府门户网站". www.moe.gov.cn. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ Birgit Zotz, Destination Tibet. Hamburg: Kovac 2010, ISBN 978-3-8300-4948-7 d-nb

.info /999787640 /04 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2011. {{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Full Text: Tibet Since 1951: Liberation, Development and Prosperity". english.www.gov.cn. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Gongkhar Airport in Tibet enters digital communication age". Xinhua News Agency. 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Tibet's fourth civil airport opens". Xinhua News Agency. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ "Tibet to have fifth civil airport operational before year end 2010". Xinhua News Agency. 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "World's highest-altitude airport planned on Tibet". news.xinhuanet.com. Xinhua News Agency. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "China to stop building extremely high plateau airports". www.chinadaily.com.cn. China Daily. 24 April 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Giri, A; Giri, S (24 August 2018). "Nepal, China agree on rail study". The Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ Chu. "China Approves New Railway for Tibet". english.cri.cn. CRI. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

Sources

edit- Laird, Thomas (2006). The Story of Tibet : Conversations with the Dalai Lama (1st ed.). New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

Further reading

edit- Dialogues Tibetan dialogues Han. [Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar]: Hannü. 2008. ISBN 978-988-97999-3-9., travelogue from Tibet – by a woman who's been travelling around Tibet for over a decade,

- Wilby, Sorrel (1988). Journey Across Tibet: A Young Woman's 1900-Mile Trek Across the Rooftop of the World. Chicago: Contemporary Books. ISBN 0-8092-4608-2., hardcover, 236 pages.

- Hillman, Ben (1 June 2010). "China's many Tibets: Diqing as a model for 'development with Tibetan characteristics?'". Asian Ethnicity. 11 (2): 269–277. doi:10.1080/14631361003779604. ISSN 1463-1369. S2CID 145011878. Retrieved 30 April 2021.