It has been suggested that X-linked genetic disease be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2024. |

Sex linked describes the sex-specific reading patterns of inheritance and presentation when a gene mutation (allele) is present on a sex chromosome (allosome) rather than a non-sex chromosome (autosome). In humans, these are termed X-linked recessive, X-linked dominant and Y-linked. The inheritance and presentation of all three differ depending on the sex of both the parent and the child. This makes them characteristically different from autosomal dominance and recessiveness.

There are many more X-linked conditions than Y-linked conditions, since humans have several times as many genes on the X chromosome than the Y chromosome. Only females are able to be carriers for X-linked conditions; males will always be affected by any X-linked condition, since they have no second X chromosome with a healthy copy of the gene. As such, X-linked recessive conditions affect males much more commonly than females.

In X-linked recessive inheritance, a son born to a carrier mother and an unaffected father has a 50% chance of being affected, while a daughter has a 50% chance of being a carrier, however a fraction of carriers may display a milder (or even full) form of the condition due to a phenomenon known as skewed X-inactivation, in which the normal process of inactivating half of the female body's X chromosomes preferably targets a certain parent's X chromosome (the father's in this case). If the father is affected, the son will not be affected, as he does not inherit the father's X chromosome, but the daughter will always be a carrier (and may occasionally present with symptoms due to aforementioned skewed X-inactivation).

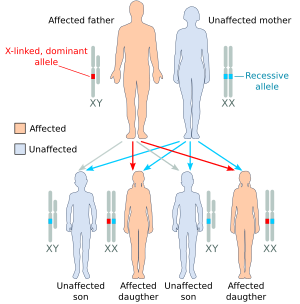

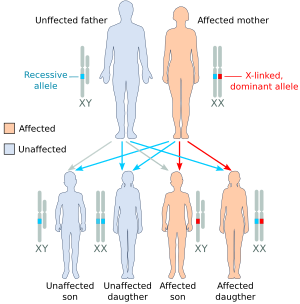

In X-linked dominant inheritance, a son or daughter born to an affected mother and an unaffected father both have a 50% chance of being affected (though a few X-linked dominant conditions are embryonic lethal for the son, making them appear to only occur in females). If the father is affected, the son will always be unaffected, but the daughter will always be affected. A Y-linked condition will only be inherited from father to son and will always affect every generation.

The inheritance patterns are different in animals that use sex-determination systems other than XY. In the ZW sex-determination system used by birds, the mammalian pattern is reversed, since the male is the homogametic sex (ZZ) and the female is heterogametic (ZW).

In classical genetics, a mating experiment called a reciprocal cross is performed to test if an animal's trait is sex-linked.

(A)

|

(B)

|

(C)

|

| Illustration of some X-linked heredity outcomes (A) the affected father has one X-linked dominant allele, the mother is homozygous for the recessive allele: only daughters (all) will be affected. (B) the affected mother is heterozygous with one copy of the X-linked dominant allele: both daughters and sons will have 50% probability to be affected. (C) the heterozygous mother is called "carrier" because she has one copy of the recessive allele: sons will have 50% probability to be affected, 50% of unaffected daughters will become carriers like their mother.[2] |

X-linked dominant inheritance

editEach child of a mother affected with an X-linked dominant trait has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation and thus being affected with the disorder. If only the father is affected, 100% of the daughters will be affected, since they inherit their father's X chromosome, and 0% of the sons will be affected, since they inherit their father's Y chromosome.[citation needed]

There are fewer X-linked dominant conditions than X-linked recessive, because dominance in X-linkage requires the condition to present in females with only a fraction of the reduction in gene expression of autosomal dominance, since roughly half (or as many as 90% in some cases) of a particular parent's X chromosomes are inactivated in females.[citation needed]

Examples

editX-linked recessive inheritance

editFemales possessing one X-linked recessive mutation are considered carriers and will generally not manifest clinical symptoms of the disorder, although differences in X chromosome inactivation can lead to varying degrees of clinical expression in carrier females since some cells will express one X allele and some will express the other. All males possessing an X-linked recessive mutation will be affected, since males have only a single X chromosome and therefore have only one copy of X-linked genes. All offspring of a carrier female have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation if the father does not carry the recessive allele. All female children of an affected father will be carriers (assuming the mother is not affected or a carrier), as daughters possess their father's X chromosome. If the mother is not a carrier, no male children of an affected father will be affected, as males only inherit their father's Y chromosome.[citation needed]

The incidence of X-linked recessive conditions in females is the square of that in males: for example, if 1 in 20 males in a human population are red–green color blind, then 1 in 400 females in the population are expected to be color-blind (1/20)*(1/20).

Examples

edit- Aarskog–Scott syndrome

- Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD)

- Bruton's agammaglobulinemia

- Color blindness

- Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome

- Congenital aqueductal stenosis (hydrocephalus)

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Fabry disease

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Haemophilia A and B

- Hunter syndrome

- Inherited nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

- Menkes disease (kinky hair syndrome)

- Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency

- Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome

Y-linked

edit- Various failures in the SRY genes

Sex-linked traits in other animals

edit- White eyes in Drosophila melanogaster flies was one of the earliest sex-linked genes discovered.[3]

- Fur color in domestic cats: the gene that causes orange pigment is on the X chromosome; thus a Calico or tortoiseshell cat, with both black (or gray) and orange pigment, is nearly always female.

- The first sex-linked gene ever discovered was the "lacticolor" X-linked recessive gene in the moth Abraxas grossulariata by Leonard Doncaster.[4]

Related terms

editIt is important to distinguish between sex-linked characters, which are controlled by genes on sex chromosomes, and two other categories.[5]

Sex-influenced traits

editSex-influenced or sex-conditioned traits are phenotypes affected by whether they appear in a male or female body.[6] Even in a homozygous dominant or recessive female the condition may not be expressed fully. Example: baldness in humans.

Sex-limited traits

editThese are characters only expressed in one sex. They may be caused by genes on either autosomal or sex chromosomes.[6] Examples: female sterility in Drosophila; and many polymorphic characters in insects, especially in relation to mimicry. Closely linked genes on autosomes called "supergenes" are often responsible for the latter.[7][8][9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Morgan, Thomas Hunt 1919. The physical basis of heredity. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company.

- ^ Genetics home reference (2006), genetic conditions illustrations, National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Morgan T.H. 1910. Sex-limited inheritance in Drosophila. Science 32: 120–122

- ^ Doncaster L. & Raynor G.H. 1906. Breeding experiments with Lepidoptera. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1: 125–133

- ^ Zirkle, Conway (1946). The discovery of sex-influenced, sex limited and sex-linked heredity. In Ashley Montagu M.F. (ed) Studies in the history of science and learning offered in homage to George Sarton on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. New York: Schuman, p167–194.

- ^ a b King R.C; Stansfield W.D. & Mulligan P.K. 2006. A dictionary of genetics. 7th ed, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-530761-5

- ^ Mallet J.; Joron M. (1999). "The evolution of diversity in warning color and mimicry: polymorphisms, shifting balance, and speciation". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 30: 201–233. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.201.

- ^ Ford E. B. (1965) Genetic polymorphism. p17-25. MIT Press 1965.

- ^ Joron M, Papa R, Beltrán M, et al. (2006). "A conserved supergene locus controls colour pattern diversity in Heliconius butterflies". PLOS Biol. 4 (10): e303. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040303. PMC 1570757. PMID 17002517.