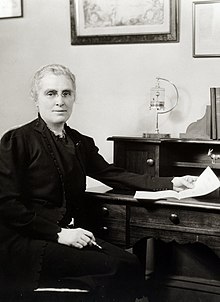

Virginia Jenckes (née Ellis; November 6, 1877 – January 9, 1975) served three terms as a U.S. Representative (March 4, 1933 – January 3, 1939) from Indiana's Sixth Congressional District. The Terre Haute, Indiana, native was the first woman from Indiana to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Alongside Kathryn O'Loughlin McCarthy, she was the second woman Representative from the Midwest and the first who was not succeeding a male relative. In 1937 she became the first American woman appointed as a U.S. delegate to the Inter-Parliamentary Union in Paris, France. The outspoken, independent-minded farmer from Vigo County was an advocate for women and became known for her support of flood control measures and repeal of Prohibition, as well as her opposition to communism. Jenckes's most significant accomplishment for her Indiana constituents was obtaining an $18 million appropriation for the Wabash River basin that eventually became law.

Virginia Ellis Jenckes | |

|---|---|

Virginia E. Jenckes | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – January 3, 1939 | |

| Preceded by | William Larrabee |

| Succeeded by | Noble J. Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 6, 1877[1] Terre Haute, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | January 9, 1975 (aged 97) Terre Haute, Indiana, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Ray Greene Jenckes

(m. 1912; died 1921) |

| Children | 1 daughter |

| Profession | U.S. Congresswoman |

While Jenckes broadly supported New Deal initiatives in general and voted with the majority of the Democrats in the U.S. Congress, she did not always follow the Democratic majority. During her later years, Jenckes became especially concerned about thwarting what she believed to be communist propaganda and its perceived threats, despite the public ridicule she received. After retiring from Congress in 1939, Jenckes served as an American Red Cross volunteer for more than twenty years. During the Hungarian uprising of 1956, she gained national attention for her efforts to assist five Catholic priests in their escape to the United States from Hungarian prisons. In 1969 Jenckes returned to Indiana, where she spent the final years of her life.

Early life

editVirginia Ellis Somes, the daughter of James Ellis Somes, a pharmacist, and Mary Oliver Somes, was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on November 6, 1877.[2][3] She attended public schools in Terre Haute, including Wiley High School, where she enrolled at the age of eleven and became the youngest student in the school's history. She left high school early to complete her formal education by taking two years of courses at Coates College for Women.[4]

In 1912, when Jencks was thirty-four, she married sixty-eight-year old Ray Greene Jenckes, a Terre Haute farmer and grain dealer. Together, they managed a 1,300-acre (530-hectare) farm along the Wabash River in western Indiana. After her husband's death in 1921, Jenckes inherited the farm along with his grain business and assumed sole responsibility for their management.[5][6] Their only child, a daughter named Virginia, was born in 1913 and died of tuberculosis on September 18, 1936, at the age of twenty-two.[2][7]

Career

editEarly years

editJenckes, who had been involved in farming in Vigo County, Indiana, since her marriage in 1912, was well aware of the damage that frequent river flooding could do to farms. Jenckes later reported that her farm had flooded nine times in fourteen months during the 1920s.[4] In 1926 Jenckes took a more active role in flood-control efforts after she and other local farmers organized the Wabash-Maumee Valley Improvement Association. Juncos served as the association's secretary until 1932.[3][6]

In 1928 Jenckes was one of two women from the Terre Haute area who traveled to the Democratic National Convention in Houston, Texas, to join others in successfully lobbying for the inclusion of one of her association's flood-control plans as a plank in the Democratic Party's national platform.[6][8] Jenckes also attained national prominence in 1928 as secretary of the National Rivers and Harbors Congress.[9]

U.S. Congresswoman

editIn 1932 Jenckes became the first woman from Indiana to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She was elected as a new Deal Democrat to represent Indiana's Sixth Congressional District in the Seventy-third Congress and was re-elected to the two succeeding Congresses. Jenckes served in the U.S. House of Representatives from March 4, 1933, to January 3, 1939.[3][6]

First term

editJenckes's first campaign for a seat in Congress began in 1932, the year after redistricting established Indiana's Sixth Congressional District, which included ten counties along the Wabash River in western Indiana. The district, a predominantly rural area of the state, extended north from Vigo County to Warren County.[6][8] With her teenaged daughter as her chauffeur, the forty-four-year-old Jenckes campaigned extensively in the new district. It is estimated that she delivered more than two hundred speeches. During her campaign, Jenckes focused on repealing Prohibition, which she felt was contributing to the decline in grain prices, along with her previous record and efforts related to flood control.[5][4]

In order to win her first election, Jenckes had to defeat two incumbents. She beat the Democratic incumbent, Courtland C. Gillen of Greencastle, Indiana, in the party's primary in May 1932. In the general election she defeated Fred S. Purnell, an eight-term Republican congressman from Attica, Indiana, who had represented the northern counties in a district that was lost in the reorganization.[10][11] Jenckes, who was one of four women in the United States who ran for a seat in Congress in 1932, easily won election in the Democrats' landslide election of 1932.[5] Jenckes received 54 percent of the vote to Purnell's 46 percent and won in seven of the new congressional district's ten counties.[11][2]

Jenckes quickly distinguished herself in Congress, despite her failure to secure the assignment she wanted on the Agricultural Committee or the Rivers and Harbors Committee. Instead of membership in these more prominent committees, Jenckes was assigned to the Mines and Mining, Civil Service, and District of Columbia committees. Jenckes retained her membership in the Civil Service and District of Columbia committees throughout her congressional career, but left the Mines and Mining committee after the conclusion of the 74th Congress.[2][9]

An advocate of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps, banking regulations, economic supports for farmers, public housing, and Social security measures, Jenckes also favored the repeal of Prohibition and supported agricultural issues, especially flood control measures.[8][10] During her first term in Congress, Jenckes took action on her campaign promise to repeal Prohibition by voting in support of the Cullen-Harrison Act, which allowed for the production, transportation, and sale of beer; it passed in March 1933. She also voted in favor of the Agricultural Adjustment Act and alternate legislation after the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Act was invalid. Through her work on the District of Columbia Committee, Jenckes sought to provide the city's voters "with a greater voice in their government," to reduce the workload of its firefighters, and to monitor its schools.[2]

In addition, Jenckes was as an advocate for U.S. veterans and American workers. She voted in favor of the Patman Greenback Bonus Bill, which extended a pay bonus to World War I veterans, and encouraged adoption of the Railroad Retirement Act. While Jenckes broadly supported New Deal initiatives, she did not always follow the Democratic majority and the Roosevelt administration's lead.[2][12] In her first vote in Congress she expressed her independent mindedness when she voted against the Economy Act of 1933 because its cuts in government expenses would reduce veterans benefits, a move that Jenckes had promised her constituents she would not allow. Jenckes's most significant accomplishment for her constituents was to successfully obtain an $18 million appropriation for the Wabash River basin that eventually became law.[5][13]

Second term

editJenckes won re-election to Congress in a close race in 1934, when she once again defeated Purnell, this time by a margin of 383 votes out of a total of 135,000 that were cast.[2][9] During her second term in office, Jenckes took a more active role in speaking on so-called women's issues.[14] Two themes characterized the remainder of her congressional career: Jenckes's "self-identification as a champion of women’s interests" and presenting herself as someone who could offer a feminine perspective on legislative issues.[15] Endorsed by the National Woman's Party during her 1934 re-election campaign, Jenckes advocated for political equality for women, although she was not a radical feminist by later-defined standards. Jenckes emphasized "traditional gender distinctions" and supported policies that would benefit women as well as consumer and business interests.[15] As one example, Jenckes urged Congress to reduce taxes on cosmetics, although she acknowledged that drug industry members had persuaded her to support the cause. Jenckes argued that cosmetics were "necessities for many working women" and the taxes were discriminatory.[15]

Jenckes tended to favor programs that provided her constituency with economic supports and voted with the majority of the New Deal Democrats in general, even though she was ambivalent about some of these programs. For example, she voted in favor of the Social Security Act in 1935, but refused to accept Social Security benefits in her later years. Jenckes commented, "I think when you give dole to people you take away their self respect."[2]

Third term

editIn 1936 Jenckes won a third term in the U.S. House, largely due to Roosevelt's landslide victory, by defeating Noble J. Johnson, her Republican challenger, only a few weeks after her daughter's death from tuberculosis.[14] Jenckes became more conservative in her later years. In 1938 she petitioned Congress to ban the Works Progress Administration from competing in construction projects because she felt the federal program "unfairly competed" with the building trades.[8][16] Jenckes was also a fervent supporter of J. Edgar Hoover and advocated congressional funding for the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[17]

Jenckes was vocal in her opposition to communism and especially active in efforts to eliminate what she believed to be subversive activities in America. Jenckes's American patriotism and strong interest in national symbols also led her to introduce legislation that required the American flag to be flown atop federal buildings.[7][15] Jenckes publicly stated that she believed the lack of flagpoles flying American flags atop public buildings in Washington, D.C., was due to the efforts of communist propagandists and called on other Americans, especially women, to join her anticommunist crusade.[14] These as well as other related comments subjected Jenckes to public ridicule and also helped to make her "a controversial figure" throughout her years in Congress.[2]

By the mid-1930s her intense patriotism and anticommunist views had overshadowed her advocacy of women's interests.[15] In 1935 Jenckes supported an amendment to a Washington, D.C., appropriations bill that prohibited teaching, advocating, or mentioning communism in the city's public schools. The House repealed the amendment in 1937, but not before disagreements over the bill caused conflicts between Jenckes and other members of the District of Columbia Committee.[2] Following re-election to her third and final term in Congress, Jenckes continued to create controversy about her anticommunist comments and ongoing distrust of Russia and Japan.[8][14] In 1937, for example, she advocated for the removal of cherry trees in Washington, D.C., that Japan had given to the United States at an earlier time as a gift of friendship. Jenckes suggested that they be replaced with American cherry trees because she thought that Japan's trees represented "a symbol of traitorism and disloyalty"[14] and a means to "open the way for their spies and propagandists."[17]

In 1937 Jenckes became the first American woman appointed as a U.S. delegate to the Inter-Parliamentary Union in Paris, France.[3] The goal of the annual gathering, which she attended with three male U.S. senators, was to promote peace and cooperation in an effort to establish representative democracies. When Jenckes returned to the United States after the conference, she expressed her growing concern about Germany's expanding building programs and urged the U.S. government to demand repayment of loans made to European countries during World War I,[9][17] a move that she thought would discourage rearmament.[10] As an isolationist, Jenckes also supported a strong defense buildup, arguing that "a strong defense was the best way to keep the United States out of war."[8]

Jenckes, a Democrat in a heavily Republican congressional district, was an unsuccessful candidate for re-election in 1938 to the Seventy-sixth Congress.[3][8] While her actions generally reflected her district's conservatism, Jenckes's work on behalf of her constituents did not to save her from defeat.[18] Jenckes ran unopposed in the Democratic primary, but Noble J. Johnson, her Republican challenger, narrowly defeated her in the general election. Jenckes, who suggested her loss was the result of ballot tampering, was among the seventy Democrats in the U.S. House who were defeated for re-election that year.[14][19]

Later years

editAfter retiring from the U.S. Congress in 1939, Jenckes remained in Washington, D.C., where she was a volunteer for the American Red Cross for nearly two decades[3][10] As a Red Cross volunteer, Jenckes worked in the first blood bank in the United States.[19]

She also retained her anticommunist views. In 1956, when Jenckes was seventy-nine, she gained national attention for her efforts to assist five Catholic priests in their escape to the United States from prisons in Budapest, Hungary, during the Hungarian uprising.[14][19] Jenckes also served as a liaison between Hungarian freedom fighters and the American government.[10]

In 1969 Jenckes came home to Indiana. She lived in Indianapolis for two years before returning to Terre Haute in 1971.[3][7]

Death and legacy

editAfter fracturing her pelvis, Jenckes was moved from her home in Terre Haute, Indiana, to a local nursing facility, where she died on January 9, 1975, at that age of ninety-seven. She was interred in Terre Haute's Highland Lawn Cemetery.[3][7]

Jenckes, who represented "populism" and American "patriotism,"[6] was among the "more colorful" politicians in Congress during the New Deal-era.[2] An outspoken congressional leader whose conservatism increased over time, she also remained a staunch anticommunist, despite the public ridicule she received.[10][7] It has been said that Jenckes was "a Cold War warrior even before, officially, there was a Cold War."[20]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Suzanne S. Bellamy, "Virginia Ellis Jenckes," in Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, ed. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Virginia Ellis Jenckes". U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Virginia Ellis Jenckes (1877–1975". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c Edward K. Spann (2005). "'Their Most Ardent Pleader for Woman's Rights': Congresswoman Virginia E. Jenckes". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 17 (1). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 38.

- ^ a b c d Bellamy, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f Edward K. Spann (September 1996). "Indiana's First Woman in Congress: Virginia D. Jenckes and the New Deal, 1932–1938". Indiana Magazine of History. 92 (3). Bloomington: Indiana University: 235–36. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Mike McCormick (2000). "Wabash Valley Profiles: Virginia Jenckes". Terre Haute Tribune-Star. Wabash Valley Visions and Voices. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Staff of the Indiana Magazine of History (March 26, 2012). "Virginia Jenckes: Populist, Patriot, Iconoclast". Indiana Public Media. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Virginia Jenckes (1878–1975)" (PDF). Indiana Commission for Women. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Indiana: Virginia Ellis Somes Jenckes (1877–1975)". Women Wielding Power: Pioneer Female State Legislators. National Women’s History Museum. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " p. 237.

- ^ Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " p. 241.

- ^ Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " p. 240.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bellamy, p. 189.

- ^ a b c d e Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " p. 242, 244.

- ^ Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress," p. 249.

- ^ a b c Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " pp. 247–48.

- ^ Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " pp. 250–51.

- ^ a b c Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " p. 252.

- ^ Spann, "Indiana's First Woman in Congress, " p. 253.

References

edit- Bellamy, Suzanne S., "Virginia Ellis Jenckes," in Gugin, Linda C., and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 187–89. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Indiana: Virginia Ellis Somes Jenckes (1877–1975)". Women Wielding Power: Pioneer Female State Legislators. National Women’s History Museum. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- McCormick, Mike (2000). "Wabash Valley Profiles: Virginia Jenckes". Terre Haute Tribune-Star. Wabash Valley Visions and Voices. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- Spann, Edward K. (September 1996). "Indiana's First Woman in Congress: Virginia D. Jenckes and the New Deal, 1932–1938". Indiana Magazine of History. 92 (3). Bloomington: Indiana University: 235–53. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- Edward K. Spann (2005). "'Their Most Ardent Pleader for Woman's Rights': Congresswoman Virginia E. Jenckes". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 17 (1). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 36–43.

- Staff of the Indiana Magazine of History (March 26, 2012). "Virginia Jenckes: Populist, Patriot, Iconoclast". Indiana Public Media. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "Virginia Jenckes (1878–1975)" (PDF). Indiana Commission for Women. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "Virginia Ellis Jenckes". U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- United States Congress. "Virginia E. Jenckes (id: J000077)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

External links

edit- Virginia Ellis Jenckes Papers, Manuscript Division, Indiana State Library, Indianapolis

This article incorporates public domain material from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress