1987 United Kingdom general election

The 1987 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday 11 June 1987, to elect 650 members to the House of Commons. The election was the third consecutive general election victory for the Conservative Party, who won a majority of 102 seats and second landslide under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, who became the first Prime Minister since the Earl of Liverpool in 1820 to lead a party into three successive electoral victories.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 650 seats in the House of Commons 326 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 75.3% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

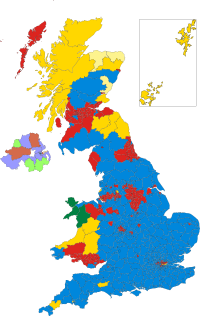

Colours denote the winning party—as shown in § Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Conservatives ran a campaign focusing on lower taxes, a strong economy and strong defence. They also emphasised that unemployment had just fallen below the 3 million mark for the first time since 1981, and inflation was standing at 4%, its lowest level since the 1960s. National newspapers also continued to largely back the Conservative government, particularly The Sun, which ran anti–Labour Party articles with headlines such as "Why I'm backing Kinnock, by Stalin".[1]

Labour, led by Neil Kinnock following Michael Foot's resignation in the aftermath of the party's landslide defeat at the 1983 general election, was slowly moving towards a more centrist policy platform, following the promulgation of a left-wing one under Foot's leadership. The main aim of the Labour Party was to re-establish itself as the main progressive centre-left alternative to the Conservatives, after the rise of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) forced Labour onto the defensive; and Labour succeeded in doing so at this general election. The Alliance between the SDP and the Liberal Party was renewed, but co-leaders David Owen and David Steel could not agree whether to support either major party in the event of a hung parliament.

The Conservatives were returned to government, having suffered a net loss of only 21 seats, which left them with 376 MPs and a reduced but still strong majority of 102 seats. Labour succeeded in resisting the challenge by the SDP–Liberal Alliance to maintain its position as HM Official Opposition. Moreover, Labour managed to increase its vote share in Scotland, Wales and the North of England. Yet Labour still returned only 229 MPs to Westminster; and in certain London constituencies which Labour had held before the election, the Conservatives actually made gains.

The election was a disappointment for the Alliance, which saw its vote share fall and suffered a net loss of one seat as well as former SDP leader Roy Jenkins losing his seat to Labour. This led to the two Alliance parties merging completely soon afterwards to become the Liberal Democrats. In Northern Ireland, the main unionist parties maintained their alliance in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Agreement; however, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) lost two seats to the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). One of the UUP losses was former Cabinet Minister Enoch Powell, famous for his stance against immigration, and formerly a Conservative MP.

To date the Conservatives have not matched or surpassed their 1987 seat total in any general election held subsequently, although they recorded a greater share of the popular vote in the 2019 general election. The 50th Parliament was the last time to date that a Conservative government has lasted a full term with an overall majority of seats in Parliament, until the 2019-2024 parliament.

The election night was covered live on the BBC, presented by David Dimbleby, Peter Snow and Robin Day.[2] It was also broadcast on ITV, presented by Sir Alastair Burnet, Peter Sissons and Alastair Stewart.

The 1987 general election saw the election of the first Black Members of Parliament: Diane Abbott, Paul Boateng and Bernie Grant, all as representatives for the Labour Party. Other newcomers included future Cabinet members David Blunkett and John Redwood, future Shadow Cabinet minister Ann Widdecombe, and future SNP Leader Alex Salmond. MPs who left the House of Commons as a result of this election include former Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan, Keith Joseph, Jim Prior, Ian Mikardo, former SDP leader and Labour Cabinet Minister Roy Jenkins, former Health Minister Enoch Powell (who had defected to the UUP in Northern Ireland from the Conservatives in 1974) and Clement Freud.

Campaign and policies

editThe Conservative campaign emphasised lower taxes, a strong economy and defence, and also employed rapid-response reactions to take advantage of Labour errors. Norman Tebbit and Saatchi & Saatchi spearheaded the Conservative campaign. However, when on "Wobbly Thursday" it was rumoured a Marplan opinion poll showed a narrow 2% Conservative lead, the "exiles" camp of David Young, Tim Bell and the advertising firm Young & Rubicam advocated a more aggressively anti-Labour message. This was when, according to Young's memoirs, Young grabbed Tebbit by the lapels and shook him, shouting: "Norman, listen to me, we're about to lose this fucking election."[3][4] In his memoirs, Tebbit defends the Conservative campaign: "We finished exactly as planned on the ground where Labour was weak and we were strong—defence, taxation, and the economy."[5] During the election campaign, however, Tebbit and party leader Margaret Thatcher argued.[6]

Bell and Saatchi & Saatchi produced memorable posters for the Conservatives, such as a picture of a British soldier's arms raised in surrender with the caption "Labour's Policy On Arms"—a reference to Labour's policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. The first Conservative party political broadcast played on the theme of "Freedom" and ended with a fluttering Union Jack, the hymn I Vow to Thee, My Country (which Thatcher would later quote in her "Sermon on the Mound") and the slogan "It's Great To Be Great Again".

The Labour campaign was a marked change from previous efforts; professionally directed by Peter Mandelson and Bryan Gould, it concentrated on presenting and improving Neil Kinnock's image to the electorate. Labour's first party political broadcast, dubbed Kinnock: The Movie, was directed by Hugh Hudson of Chariots of Fire fame, and concentrated on portraying Kinnock as a caring, compassionate family man. It was filmed at the Great Orme in Wales and had "Ode to Joy" as its music.[7] He was particularly critical of the high unemployment that the government's economic policies had resulted in, as well as condemning the wait for treatment that many patients had endured on the National Health Service. Kinnock's personal popularity jumped 16 points overnight following the initial broadcast.[8]

On 24 May, Kinnock was interviewed by David Frost and claimed that Labour's alternative defence strategy in the event of a Soviet attack would be "using the resources you've got to make any occupation totally untenable".[citation needed] In a speech two days later Thatcher attacked Labour's defence policy as a programme for "defeat, surrender, occupation, and finally, prolonged guerrilla fighting ... I do not understand how anyone who aspires to Government can treat the defence of our country so lightly".[9]

During the 1987 election campaign the Conservative Party issued attack posters which claimed that the Labour Party wanted the book Young, Gay and Proud to be read in schools, as well as Police: Out of School, The Playbook for Kids about Sex,[b][10][11] and The Milkman's on his Way,[c] which, according to the Monday Club's Jill Knight MP – who introduced Section 28 and later campaigned against same-sex marriage[12] – were being taught to "little children as young as five and six", which contained "brightly coloured pictures of little stick men showed all about homosexuality and how it was done", and "explicitly described homosexual intercourse and, indeed, glorified it, encouraging youngsters to believe that it was better than any other sexual way of life".[13]

Endorsements

editThe following newspapers endorsed political parties running in the election in the following ways:[14]

Opinion polling

editTimeline

editThe Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher visited Buckingham Palace on 11 May and asked the Queen to dissolve Parliament on 18 May, announcing that the election would be held on 11 June. The key dates were as follows:[15][16]

| Monday 18 May | Dissolution of the 49th Parliament and campaigning officially begins |

| Wednesday 10 June | Campaigning officially ends |

| Thursday 11 June | Polling day |

| Friday 12 June | The Conservative Party wins with a majority of 102 to retain power |

| Wednesday 17 June | 50th Parliament assembles |

| Thursday 25 June | State Opening of Parliament |

Results

editThe Conservatives were returned by a second landslide victory after their first in 1983,[17] with a comfortable majority, down slightly on 1983 with a swing of 1.5% towards Labour. This marked the first time since the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832 that a party leader had won three consecutive elections, although the Conservative Party had won three consecutive contests in the 1950s under different leaders (Churchill in 1951, Eden in 1955 and Macmillan in 1959) and early in the century, the Liberals also had three successive wins under two leaders (Henry Campbell-Bannerman in 1906 and H. H. Asquith twice in 1910). The Conservative lead over Labour of 11.4% was the second-greatest for any governing party since the Second World War; only being bettered by the previous 1983 result.[18]

The BBC announced the result at 02:35. Increasing polarisation marked divisions across the country; the Conservatives dominated Southern England and took additional seats from Labour in London and the rest of the South, but performed less well in Northern England, Scotland and Wales, losing many of the seats they had won there at previous elections. Yet the overall result of this election proved that the policies of Margaret Thatcher retained significant support, with the Conservatives given a third convincing majority.

Despite initial optimism and the professional campaign run by Neil Kinnock, the election brought only twenty additional seats for Labour from the 1983 Conservative landslide. In many southern areas, the Labour vote actually fell, with the party losing seats in London. However, it represented a decisive victory against the SDP–Liberal Alliance and marked out the Labour Party as the main contender to the Conservative Party. This was in stark contrast to 1983, when the Alliance almost matched Labour in terms of votes; although Labour had almost 10 times as many seats as the Alliance due to the structure of the First-Past-The-Post voting system.

The result for the Alliance was a disappointment, in that they had hoped to overtake Labour as the Official Opposition in the UK in terms of vote share. Instead, they lost Roy Jenkins' seat and saw their vote share drop by almost 3%, with a widening gap of 8% between them and the Labour Party (compared to a 2% gap four years before). These results would eventually lead to the end of the Alliance and the birth of the Liberal Democrats.

Most of the prominent MPs retained their seats. Notable losses included: Enoch Powell (the controversial former Conservative Cabinet Minister who had defected to the Ulster Unionist Party), Gordon Wilson (leader of the Scottish National Party) and two Alliance members: Liberal Clement Freud and former SDP leader Roy Jenkins (a former Labour Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer). Neil Kinnock increased his share of the vote in Islwyn by almost 12%. Margaret Thatcher increased her share of the vote in her own seat in Finchley, but the Labour vote increased in the Prime Minister's constituency; thereby slightly reducing her majority.

In Northern Ireland, the various unionist parties maintained an electoral pact (with few dissenters) in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Agreement. However, the Ulster Unionists lost two seats to the Social Democratic and Labour Party.

The election victory won by the Conservatives could also arguably be attributed to the rise in average living standards that had taken place during their time in office. As noted by Dennis Kavanagh and David Butler in their study on the 1987 general election:

Since 1987 the Conservatives had located a large constituency of "winners", people who have an interest in the return of a Conservative government. It includes much of the affluent South, home-owners, share-owners, and most of those in work, whose standard of living, measured in post-tax incomes, has risen appreciably since 1979.[19]

| Candidates | Votes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Leader | Stood | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |

| Conservative | Margaret Thatcher | 633 | 376[a] | 9 | 30 | −21 | 57.85 | 42.2 | 13,760,583 | −0.2 | |

| Labour | Neil Kinnock | 633 | 229 | 26 | 6 | +20 | 35.23 | 30.8 | 10,029,807 | +3.2 | |

| Alliance | David Owen & David Steel | 633 | 22 | 5 | 6 | −1 | 3.38 | 22.6 | 7,341,633 | −2.8 | |

| SNP | Gordon Wilson | 72 | 3 | 3 | 2 | +1 | 0.46 | 1.3 | 416,473 | +0.2 | |

| UUP | James Molyneaux | 12 | 9 | 0 | 2 | −2 | 1.38 | 0.8 | 276,230 | 0.0 | |

| SDLP | John Hume | 13 | 3 | 2 | 0 | +2 | 0.46 | 0.5 | 154,067 | +0.1 | |

| Plaid Cymru | Dafydd Elis-Thomas | 38 | 3 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.46 | 0.4 | 123,599 | 0.0 | |

| Green | N/A | 133 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 89,753 | +0.1 | ||

| DUP | Ian Paisley | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.3 | 85,642 | −0.2 | |

| Sinn Féin | Gerry Adams | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 83,389 | 0.0 | |

| Alliance | John Alderdice | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 72,671 | 0.0 | ||

| Workers' Party | Tomás Mac Giolla | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 19,294 | +0.1 | ||

| UPUP | James Kilfedder | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 18,420 | 0.0 | |

| Real Unionist | Robert McCartney | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 14,467 | N/A | ||

| Communist | Gordon McLennan | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6,078 | 0.0 | ||

| Protestant Unionist | George Seawright | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5,671 | N/A | ||

| Red Front | N/A | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,177 | N/A | ||

| Orkney and Shetland Movement | John Goodlad | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,095 | N/A | ||

| Moderate Labour | Brian Marshall | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,269 | N/A | ||

| Monster Raving Loony | Screaming Lord Sutch | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,951 | 0.0 | ||

| Workers Revolutionary | Sheila Torrance | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,721 | 0.0 | ||

| Independent Liberal | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 686 | 0.0 | ||

| BNP | John Tyndall | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 553 | 0.0 | ||

| Spare the Earth | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 522 | N/A | ||

| Government's new majority | 102 |

| Total votes cast | 32,529,578 |

| Turnout | 75.3% |

Votes summary

editSeats summary

editIncumbents defeated

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b The seat and vote count figures for the Conservatives given here include the Speaker of the House of Commons

- ^ Authored by Joani Blank

- ^ Authored by David Rees

References

edit- ^ Thomas, James (7 May 2007). Popular Newspapers, the Labour Party and British Politics. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-135-77373-1.

- ^ BBC Election 1987 coverage on YouTube

- ^ Campbell 2003, p. 522.

- ^ Oborne, Peter (19 March 2005). "Has Gordon Brown delivered his last Budget? The truth is that Blair hasn't yet decided". The Spectator. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Tebbit 1988, p. 336.

- ^ Thatcher 1993, p. 584.

- ^ "World in Motion", The 80s with Dominic Sandbrook, BBC, retrieved 2 July 2018

- ^ Butler & Kavanagh 1988, p. 154.

- ^ Speech to Conservative Rally in Newport, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, 26 May 1987, retrieved 2 July 2018

- ^ Sanders, Sue; Spraggs, Gill (1989). "Section 28 and Education" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Booth, Janine (December 1997). "The story of Section 28". Workers' Liberty. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "Baroness Knight: Parliament can't help blind people see, so can't help "artistic" gays get married". Pink News. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Quoted in Hansard, "Lords Hansard text for 6 Dec 1999 (191206-10)". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2008., 6 December 1999, Column 1102.

- ^ 'Newspaper support in UK general elections' (2010) on The Guardian.

- ^ "Parliamentary Election Timetables" (PDF) (3rd ed.). House of Commons Library. 25 March 1997. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Queen's Speech". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 25 June 1987. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "1983: Thatcher wins landslide victory". BBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ David Butler; Robert Waller (1987). "Survey of the voting. Election of haves and have-nots". The Times Guide to the House of Commons June 1987. London: Times Books Ltd. p. 253. ISBN 0-7230-0298-3.

- ^ Butler & Kavanagh 1988, p. 277.

Biographies

edit- Campbell, John (2003), Margaret Thatcher: The Iron Lady, vol. 2, Pimlico, ISBN 978-0-7126-6781-4

- Tebbit, Norman (1988), Upwardly Mobile, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-79427-1

- Thatcher, Margaret (1993), The Downing Street Years, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-255354-4

Scholarly sources

edit- Butler, David E.; Kavanagh, Dennis (1988), The British General Election of 1987, the standard scholarly study.

- Craig, F. W. S. (1989), British Electoral Facts: 1832–1987, Dartmouth: Gower, ISBN 0900178302

- Craig, F. W. S., ed. (1990), British General Election Manifestos, 1959–1987

- Crewe, Ivor; Harrop, Martin (1989), Political Communications: The General Election Campaign of 1987, p. 316

- Galbraith, John W.; Rae, Nicol C. (1989), "A Test of the Importance of Tactical Voting: Great Britain, 1987", British Journal of Political Science, 19 (1): 126–136, doi:10.1017/S0007123400005366, JSTOR 193792, S2CID 154797699

- Scott, Len (2012), "Selling or Selling Out Nuclear Disarmament? Labour, the Bomb, and the 1987 General Election", International History Review, 34 (1): 115–137, doi:10.1080/07075332.2012.620242, S2CID 154319694

- Stewart, Marianne C.; Clarke, Harold D. (1992), "The (un)importance of party leaders: Leader images and party choice in the 1987 British election", Journal of Politics, 54 (2): 447–470, doi:10.2307/2132034, JSTOR 2132034, S2CID 154890477, says the well-organised, media-wise Labour campaign helped Kinnock, but he was hurt by Conservative momentum and Thatcher's image as a decisive leader. Leadership images proved more important in voters' choices than did party identification, economic concerns, etc.

Manifestos

edit- The Next Moves Forward, 1987 Conservative Party manifesto

- Britain will win with Labour, 1987 Labour Party manifesto

- Britain United: The Time Has Come, 1987 SDP–Liberal Alliance manifesto