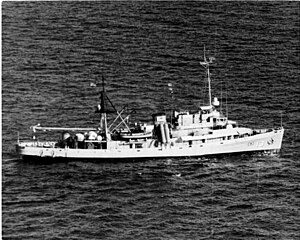

USS Kittiwake (ASR-13) was a United States Navy Chanticleer-class submarine rescue vessel in commission from 1946 to 1994.

USS Kittiwake (ASR-13)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake | The kittiwake, any of several gulls of the genus Rissa, found along the coast of North America |

| Launched | 10 July 1945 |

| Sponsored by | Mrs. Howard S. Rue, Jr. |

| Commissioned | 18 July 1946 |

| Decommissioned | 30 September 1994 |

| Stricken | 30 September 1994 |

| Fate | Sunk as artificial reef in January 2011 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Chanticleer-class submarine rescue vessel |

| Displacement | 1,780 tons |

| Length | 251 ft 4 in (76.61 m) |

| Draught | 14 ft 3 in (4.34 m) |

| Speed | 16 knots |

| Complement | 102 officers and enlisted |

| Armament | .50 caliber machine gun |

Construction and commissioning

editThe USS Kittiwake was initially launched on 13 May 1945 at the Savannah Machine & Foundry Co., Savannah, Georgia.[1] It was named for the Kittiwake gull, the most oceanic of all the gulls and the only regular ocean-crosser and mid-ocean forager.[1]

The ship launching was sponsored by Mrs. Howard S. Rue, Jr., formerly Jacqueline Bond Jones, daughter of Lieutenant Commander Roy Kehlor Jones, commanding officer of the submarine, USS S-4 (SS-109) which tragically sunk following an accidental collision with the USCG Paulding off Provincetown, Massachusetts on 17 December 1927, resulting with a loss of all 40 men aboard the submarine.[2][3]

The Kittwake was commissioned on 18 July 1946.

Service history

editAfter shakedown, Kittiwake departed Charleston, South Carolina, 3 October for Balboa, Canal Zone, arriving 8 October. Assigned to support and rescue duty with Submarine Squadron 6, the submarine rescue ship accompanied submarines during sea trials and maneuvers to monitor diving operations, practice underwater rescue procedures, and recover practice torpedoes. While based at Balboa, her operations carried her to the Virgin Islands, to Puerto Rico, and along the Atlantic coast to the Davis Strait.

In an impressive operational training mission in August 1948, the Kittwake participated in a rescue and salvage exercise with the submarine USS Sea Owl, during which the sub lay inert on the bottom of Panama Bay with simulated casualties. The Kittiwake rescued the "survivors" and raised the submarine to the surface.[4]

On 21 April 1949, a Kittiwake crewman, gunner’s mate first class, C. M. Prickett established a new open sea diving record when he dived from the decks of the Kittiwake to a depth of 501 feet while in the Panama area.[1]

Departing Balboa on 31 May 1949, Kittiwake arrived at Norfolk, Virginia, on 6 June to continue duty with SUBRON 6.

From 17 January to 1 February 1950, she provided divers and equipment during salvage operations to free the famous battleship USS Missouri, grounded in tidal banks off Thimble Shoals, Virginia near Hampton Roads, caused by officers on her navigation bridge mistaking buoys marking the small boat channel for defining a recently installed electronic range which ran almost parallel to the main ship channel as those marking the safe route toward the Thimble Shoals Channel.[1][5] The Kittiwake (along with the USS Pawcatuck) supplied power for the helpless battleship and its divers used high pressure hoses to flush away muddy sand which had fouled the battlewagon's propellers, while Navy tanker ships lightened the Missouri's load of fuel by pumping their own tanks to capacity, then going to the piers to unload them, and returning to the Missouri to repeat the process[5].

On 14 December 1953, she hit the headlines again with her rescue of 55 sailors from the waters of Hampton Roads after a 50-foot motor launch from the USS Pittsburg had capsized in heavy seas.

During much of the 1950s, she cruised the Atlantic from New England to the Caribbean while supporting ships of Submarine Force U.S. Atlantic Fleet.

In May 1956, Lt. Cmdr. W. H. Hibbs assumed command of the Kittiwake from Lt. Cmdr. W. D. Buckbee, who was ordered to the New London submarine base as officer in charge of the submarine escape tank there. Prior to assuming command, Hibbs attended the Armed Forces Staff College in Norfolk and the Deep Sea Divers School in Washington DC.

While on station off the coast of Cape Canaveral, Florida, 20 July 1960, the Kittiwake stood ready to assist the fleet ballistic missile submarine USS George Washington (SSBN-598) as George Washington successfully launched the first two Polaris ballistic missiles ever fired from a submerged submarine.

Kittiwake continued operating from Norfolk until 1 August 1961, when she departed for the Mediterranean. Arriving at Rota, Spain, on 15 August, she cruised the Mediterranean from Spain to Greece while deployed with the United States Sixth Fleet. After supporting submarine maneuvers from Piraeus, Greece, from 20 September to 9 October, she departed the Mediterranean on 8 November and arrived in Norfolk on 18 November. She then conducted operations from Norfolk for the next 18 months. While on duty off Key West 2 February 1963, she sighted a Cuban boat, Jose Maria Perez and took on board 12 refugees (including three children) fleeing Cuba; they were carried to safety at Key West.

Departing Charleston, South Carolina, 16 April, Kittiwake arrived at St. Nazaire, France, 3 May with two Landing Craft Utility (LCU's) in tow. She proceeded to the Mediterranean on 10 May and reached Rota on the 14th. She participated in fleet operations for more than two months before departing Rota 31 July for the United States. Returning to Norfolk on 10 August 1963, she resumed training and support operations with submarines along the Atlantic coast. Through 1964 and 1965, Kittiwake continued her role in maintaining the readiness of individual submarines, which were to carry out their defense and deterrence missions effectively. She escorted them as they left the United States East Coast shipyards for sea trials, standing ready to come to their rescue should difficulties arise. Constant exercise in using weapons by submarines was furnished by Kittiwake, such as running as a target and recovering exercise torpedoes and mines. The operations ranged from the Virginia Capes to the Atlantic missile range off Florida. On 6 April 1965, she departed Norfolk with submarines for exercises off the coast of Spain, thence to the Mediterranean Sea.

Kittiwake departed Toulon 31 May 1965, to operate from Rota, Spain, in support of the fleet ballistic missile submarines of Submarine Squadron 16: USS Andrew Jackson (SSBN-619), USS Woodrow Wilson (SSBN-624), USS James Madison (SSBN-627), and USS Nathan Hale (SSBN-623). Following torpedo recovery and training off the coast of Spain, she sailed for Holy Loch, Scotland 30 June 1965, to give support to Submarine Squadron 14 there. She recovered torpedoes for the fleet ballistic missile submarines USS James Monroe (SSBN-622) and USS John Adams (SSBN-620), provided underway training for men of the submarine tender USS Hunley (AS-31), then sailed 20 July for Norfolk, arriving 30 July 1965.[6][7] During the autumn months, Kittiwake guarded new Polaris submarines, USS Lewis and Clark (SSBN-644) and USS Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641), during their builder's sea trials prior to commissioning.

Kittiwake operated on the U.S. East Coast and in the Caribbean until sailing for the Mediterranean 8 July 1966. She reached the Bay of Cádiz on the 20th and transited the straits two days later. She operated in the Mediterranean until emerging at Rota, Spain, 1 September. She headed for Holy Loch on the 6th and arrived on the 11th. Four days later she was ordered to the North Sea to assist in locating and salvaging the German submarine Hai (S-171). She reached the scene of the tragedy on 17 September and remained on hand assisting salvage operations until the 20th. She continued to operate off Western Europe until returning to Norfolk on 13 November. Kittiwake operated on the U.S. East Coast into 1967.

In May 1968, USS Kittiwake was sent to the mid-Atlantic as part of the fleet searching for the missing attack submarine USS Scorpion (SSN-589). Kittiwake was assigned to the search until August 1968. During the search, another submarine, the Pargo, discovered an uncharted wreck on the edge of the Baltimore-Norfolk channel entrance of Chesapeake Bay, and divers from another submarine rescue ship, the Sunbird, sighted the wreck and erroneously reported if to be a WWII vintage German submarine, not the missing Scorpion. Lt. Cmdr. Robert James, commander of the Kittiwake at that time, was given orders to investigate the sunken vessel more closely. His first pair of divers made positive identification that the ship was a submarine. They also reported discovering the ship's anchor chain, 2½ inches in diameter, adequate for an aircraft carrier. With this inconsistency, James sent down a second set of divers farther aft. They took a portable television camera on their dive which confirmed the anchor size and explained what had first appeared to be deck guns were really two cargo booms lying horizontally on the deck. At this point, the Kittiwake's master diver, Dean Hawes, who usually supervised all diving operations, requested and was granted permission to go down and make his own personal evaluation. His report, described by James as "explicit," said the earlier "submarine" identification was understandable but in error. Based on Hawes' analysis, James reported the sunken hulk as a merchant ship. Deteriorating weather conditions forced the Kittiwake to break off the investigation and head for port. Later, after filing all of its reports and confirming the original charting of the wreck, the Kittiwake was deployed to Europe. [8]

While there, diver Dean Hawes read a magazine account about the Navy's most baffling mystery -- the disappearance of the merchant ship USS Cyclops in 1918, enroute to Baltimore from Barbados with a load of manganese ore and 309 passengers and crew, and vanished without a trace -- that caused his memory to flash back to that dive. The picture of the strange looking Cyclops was exactly like the sunken ship he had described to James the year before. He was sure he and the other divers had discovered the Cyclops. All the divers who had been on her deck submitted their individual impressions to a Navy artist and the composite rendering which resulted, James said, "looked remarkably like Cyclops." The Navy was convinced enough to order the Kittiwake back to sea and back to the site of the mysterious unnamed and unidentified merchant ship. To ensure ease in locating the wreck, the Navy directed another submarine with highly sophisticated sonar to accompany the Kittiwake. For three days starting June 9, 1970, the ships searched the exact location where twice before the block-long wreck had been seen. Their report this time was similar to another report made many years before by the flotilla of ships that searched the Atlantic for the Cyclops: There was no trace of the wreck.[8]

In June 1973, the Navy indicated that it would once again send the salvage ship Kittiwake to the wreck area in September 1973 in an effort to relocate the unidentified sunken vessel as a training exercise for Navy divers.[9]

In November 1975, the ship was on a 2½-month deployment.[10]

This section needs expansion with: history for 1968 through 1984. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

On 12 April 1980, the Kittiwake docked in Port Everglades, Florida for a public open house, demonstrating deep-sea diving equipment and rescue gear to the public, with crew members discussing their jobs and the ship's mission.[11][12]

On 23 January 1983, Kittiwake became the first U.S. Navy ship to visit the Port of Corpus Christi in almost six years. It was docked at Cargo Dock 1 and open to the public over the following weekend, with Navy scuba diving demonstrations conducted twice daily.[13][14][15][16]

On 23 April 1984, Kittiwake collided with the attack submarine USS Bergall (SSN-667) at Norfolk, Virginia, while Bergall was moored to the pier astern of her. Kittiwake was getting underway for the first time since she had undergone maintenance, during which her main drive motor was re-wired improperly, causing it and the screw it drove to rotate in the opposite direction from that ordered by personnel on Kittiwake's bridge. This was unknown to Kittiwake's bridge personnel, who found that Kittiwake started to move astern when they were expecting her to move forward. Noting the backward motion, they ordered an increase in the motor drive speed to correct it and get Kittiwake moving forward. However, they unwittingly caused Kittiwake to move farther astern and at a higher speed. Still not realizing that Kittiwake's main drive motor was operating in reverse of what they expected, Kittiwake's bridge personnel then ordered another increase in Kittiwake's forward speed, which served only to increase her speed astern. This continued until Kittiwake's stern backed into Bergall's sonar dome, causing damage to the Bergall's sonar dome and the USS Kittiwake's propeller.

This section needs expansion with: history for 1984 through 1994. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

In January 1986, as the Kittiwake started as a routine training assignment in the Gulf of Mexico, it encountered three diversions on its return trip to Norfolk. It took its first diversion when it was ordered to salvage an Air Force F-16 jet that crashed off the Florida coast. Then, early in February, as the Kittiwake headed for her homeport, the ship was assigned to Cape Canaveral to assist in the space shuttle Challenger recovery efforts.[17] Popular folklore of the ship recovering the Challenger's "black box"[18] are in error -- it actually recovered one of the Challenger’s Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) from a depth of 177 feet (54m).[19] Finally, as the ship rounded Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, it was called on a third time to help a 39-foot sailboat that had lost its mast and was foundering in waters known as the graveyard of the Atlantic. The Kittiwake rescued the sailboat and towed it back to Norfolk, ending its 82 days at sea.[20]

On 5 December 1989, the USS Kittiwake provided surface support during a Navy Trident missile test in the Atlantic Ocean. The environmental group, Greenpeace had found out about the testing and had sent ships to protest this exercise. Greenpeace attacked the USS Kittiwake by hitting her aft port side with the bow of the Greenpeace ship. The Kittiwake, along with the USS Grasp, a rugged steel-hulled rescue and salvage ship, sandwiched the 190-foot Greenpeace vessel between the two Navy vessels, leaving a 3-foot-long gash in the hull of the MV Greenpeace that crew members stuffed with mattresses to keep the water out, hosed down occupants of the Greenpeace vessel with cold sea water to discourage them from interfering, and disabled the engines by shooting seawater down the smoke stack of the ship into the engine room, making her dead in the water in rough seas, and thereby ending the morning-long cat-and-mouse game nearly 40 miles east of Cape Canaveral.[21][22]

Decommissioning and disposal

editKittiwake was decommissioned on 30 September 1994 and struck from the Naval Vessel Register on the same day. Her title was transferred in November 2008 for an undisclosed amount to the government of the Cayman Islands for the purpose of using Kittiwake to form a new artificial reef.[23][24][25] Originally intended to be sunk in June 2009,[26] she was finally sunk off Seven Mile Beach, Grand Cayman, on 5 January 2011 in Marine Park.[27][28][29] The wreck has since become one of the most popular dive and snorkel sites in Grand Cayman, with its moorings often in constant daily use by local dive operators.[30]

A 2011 episode of the documentary television series Monster Moves covered moving and sinking the ship. Divers are not allowed to touch or take anything from the dive site. At its most shallow, the wreck of Kittiwake was 15 feet (4.6 meters) below the water's surface and at its deepest, 64 feet (20 meters) below the surface.[27] In October 2017, the wreck moved towards a nearby natural reef. It fell to its port side due to wave action from passing Tropical Storm Nate. The wreck is now approximately 20 ft (6.1 m) deeper at its most shallow.[31]

Awards

edit- World War II Victory Medal

- National Defense Service Medal with two stars

References

edit- ^ a b c d Stublen, Nash (21 April 1957). "Submarine Aide Kittiwake In Armed Forces Day Ships". The Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk, Virginia). pp. 6-D. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Roy Kehlor Jones". On Eternal Patrol - Lost Submariners of the U.S. Navy. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "The Loss of USS S-4 (SS-109)". Submarine Force Library and Museum Association. 17 December 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Navy Public Affairs Office (24 August 1948). "William L. Hiles On USS Kittiwake". The Times Recorder (Zanesville, Ohio). p. 3. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Barron, Charlton W. (18 January 1950). "Battleship Mistook Shallow Channel Buoys For Markers Defining Safe Route To Capes: Grounded Missouri Poses Real Test in Salvage". Ledger-Star (Norfolk, Virginia). pp. 1, 12. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Navy Public Affairs Office (11 August 1965). "Clearfield Returns From Navy Cruise". The Progress (Clearfield, Pennsylvania). p. 7. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Navy Public Affairs Office (9 August 1965). "Don Jones serves aboard target ship". Daily Press (Victorville, California). pp. A-6. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Quinlan, James (1 July 1973). "Cyclops Mystery: Jupiter Man Sure His Ship Spotted Wreck". The Palm Beach Post (West Palm Beach, Florida). pp. B1, B9. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Associated Press (22 June 1973). "Navy Plans Search: Ship Lost In '18 Possibly Spotted". The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina). pp. 11A. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Michael Stahlman on submarine Kittiwake [sic], Gary Chitwood aboard Kittiwake". St. Clair Chronicle (St. Clair, Missouri). 26 November 1975. p. 8. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Ship Ahoy! It's the Kittiwake". The Miami Herald (Miami, Florida). 12 April 1980. pp. 7BR. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Navy Public Affairs Office (11 April 1980). "Sub rescue ship open to public tomorrow". Fort Lauderdale News (Fort Lauderdale, Florida). pp. 4B. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brown, Hal (24 January 1983). "USS Kittiwake arrives for visit". Corpus Christi Times (Corpus Christi, Texas). pp. 10A. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Weekend! around the city: Tours of Kittiwake". Corpus Christi Caller-Times (Corpus Christi, Texas). 21 January 1983. p. 8. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Gongora, George (24 January 1983). "USS Kittiwake heads home". Corpus Christi Times (Corpus Christi, Texas). p. 1. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Gongore, George (22 January 1983). "Jules Verne comes to life at USS Kittiwake". Corpus Christi Caller-Times (Corpus Christi, Texas). p. 1. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Taylor, Jeremy (28 January 2011). "Sink and Swim". Financial Times.

- ^ So-called "Black Boxes" or flight recorders are associated with aircraft, not space shuttles -- the Challenger was equipped with a cockpit voice recorder.

- ^ McArthur, Drew (18 May 2020). "Return to the Kittiwake". Diver Magazine. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Navy Public Affairs Center (4 August 1986). "Local man helped with Challenger recovery". The Brattleboro Reformer (Brattleboro, Vermont). p. 9. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Long, Phil (5 December 1989). "Missile soars aloft after skirmish: Navy bumps Greenpeace ship from Trident site". The Miami Herald (Miami, Florida). pp. 1A. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Associated Press (5 December 1989). "Navy ships hit Greenpeace vessel to keep it from test area". The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland). pp. A17. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Diving to Become More Exciting". Cayman Islands Government. [permanent dead link]

- ^ McAdam, Diana (27 February 2010). "New Kittiwake site set to enthral". The Daily Telegraph (London, England). pp. 13 (Cayman Islands Supplement). Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bodnarchuk, Kari (5 December 2010). "This old ship: new reef and dive site". The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts). pp. M2. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Ship sunk to create artificial reef". Channel 4 News. PA News. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Kittiwake, A Diver's Treasure Chest". Cayman Islands. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Mark (8 November 2015). "Wrecked! Sunken ships are a diver's dream". Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona). pp. 4U. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Associated Press (16 January 2011). "Cayman Islands sinks U.S. ship to create reef". Rapid City Journal (Rapid City, South Dakota). pp. C3. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Heinrich, Erik (20 May 2018). "Grand Cayman thrills with Kittiwake wreck dive and Stingray City". The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts). pp. M4. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Kittiwake toppled onto natural reef". Cayman News Service. 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- This article includes information collected from the Naval Vessel Register, which, as a U.S. government publication, is in the public domain. The entry can be found here.

- Photo gallery of USS Kittiwake (ASR-13) at NavSource Naval History