The energy policy of the United States is determined by federal, state, and local entities. It addresses issues of energy production, distribution, consumption, and modes of use, such as building codes, mileage standards, and commuting policies. Energy policy may be addressed via legislation, regulation, court decisions, public participation, and other techniques.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Federal energy policy acts were passed in 1974, 1992, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009,[1] 2020, 2021, and 2022, although energy-related policies have appeared in many other bills. State and local energy policies typically relate to efficiency standards and/or transportation.[2]

Federal energy policies since the 1973 oil crisis have been criticized for having an alleged crisis-mentality, promoting expensive quick fixes and single-shot solutions that ignore market and technology realities.[3][4]

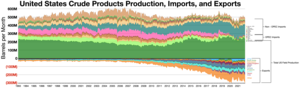

Americans constitute less than 5% of the world's population but consume 26% of the world's energy[5] to produce 26% of the world's industrial output. Technologies such as fracking and horizontal drilling allowed the United States to become the world's top oil fossil fuel producer in 2014.[6] In 2018, US exports of coal, natural gas, crude oil and petroleum products exceeded imports, achieving a degree of energy independence for the first time in decades.[7][8][9] In the second half of 2019, the US was the world's top producer of oil and gas.[10] This energy surplus ended in 2020.[11][12]

Various multinational groups have attempted to establish goals and timetables for energy and other climate-related policies, such as the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2015 Paris Agreement.

History

editIn the early days of the Republic, energy policy allowed free use of standing timber for heating and industry. Wind and water provided energy for tasks such as milling grain. In the 19th century, coal became widely used. Whales were rendered into lamp oil.[13] Coal gas was fractionated for use as lighting and town gas. Natural gas was first used in America for lighting in 1816.[14] Since then, natural gas has grown in importance, especially for electricity generation. US natural gas production peaked in 1973,[15] and the price has risen significantly since then.

Coal provided the bulk of US energy needs well into the 20th century. Most urban homes had a coal bin and a coal-fired furnace. Over the years these were replaced with oil furnaces that were easier and safer to operate.[16]

From the early 1940s, the US government and the oil industry entered into a mutually beneficial collaboration to control global oil resources.[17] By 1950, oil consumption exceeded that of coal.[18][19] Abundant oil in California, Texas, Oklahoma, as well as in Canada and Mexico, coupled with its low cost, ease of transportation, high energy density, and use in internal combustion engines, led to its increasing use.[20]

Following World War II, oil heating boilers replaced coal burners along the Eastern Seaboard; diesel locomotives replaced coal-fired steam engines; oil-fired power plants dominated; petroleum-burning buses replaced electric streetcars, and citizens bought gasoline-powered cars. Interstate Highways helped make cars the major means of personal transportation.[20] As oil imports increased, US foreign policy was drawn into Middle Eastern politics, seeking to maintain a steady supply via actions such as protecting Persian Gulf sea lanes.[21]

Hydroelectricity was the basis of Nikola Tesla's introduction of the US electricity grid, which started at Niagara Falls, New York, in 1883.[22] Electricity generated by major dams, such as the TVA Project, Grand Coulee Dam and Hoover Dam, still produce some of the cheapest ($0.08/kWh) electricity. Rural electrification strung power lines to many more areas.[13][23]

A National Maximum Speed Limit of 55 mph (88 km/h) was imposed in 1974 (and repealed in 1995) to help reduce energy consumption. Corporate Average Fuel Economy (aka CAFE) standards were enacted in 1975 and progressively tightened over time to compel manufacturers to improve vehicle mileage.[24] Year-round Daylight Saving Time was imposed in 1974 and repealed in 1975. The United States Strategic Petroleum Reserve was created in 1975.

The Weatherization Assistance Program[25] was enacted in 1977. On average, low-cost weatherization reduces heating bills by 31% and overall energy bills by $358 per year at 2012 prices. Increased energy efficiency and weatherization spending has a high return on investment.[26]

On August 4, 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed into law The Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 (Pub. L. 95–91, 91 Stat. 565, enacted August 4, 1977), which created the United States Department of Energy (DOE).[27] The new agency, which began operations on October 1, 1977, consolidated the Federal Energy Administration, the Energy Research and Development Administration, the Federal Power Commission, and programs of various other agencies. Former Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, who served under Presidents Nixon and Ford during the Vietnam War, was appointed as its first secretary.

On June 30, 1980, Congress passed the Energy Security Act, which reauthorized the Defense Production Act of 1950 and enabled it to cover domestic energy supplies. It also obligated the federal government to promote and reform the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, biofuels, geothermal power, acid rain prevention, solar power, and synthetic fuel commercialization.[28] The Defense Production Act was further reauthorized in 2009, with modifications requiring the federal government to promote renewable energy, energy efficiency, and improved grid and grid storage installations with its defense procurements.[29][30]

The federal government provided substantially larger subsidies to fossil fuels than to renewables in the 2002–2008 period. Subsidies to fossil fuels totaled approximately $72 billion, a direct cost to taxpayers, over the study period. Subsidies for renewable fuels totaled $29 billion over the same period.[31]

In some cases, the US used energy policy to pursue other international goals. Richard Heinberg claimed that a declassified CIA document showed that, during the Reagan administration, the US used oil prices as leverage against the Soviet Union economy by working with Saudi Arabia to keep oil prices low, thus decreasing the value of the USSR's petroleum export industry.[32]

The 2005 Energy Policy Act (EPA) addressed (1) energy efficiency; (2) renewable energy; (3) oil and gas; (4) coal; (5) tribal energy; (6) nuclear matters; (7) vehicles and motor fuels, including ethanol; (8) hydrogen; (9) electricity; (10) energy tax incentives; (11) hydropower and geothermal energy; and (12) climate change technology.[33] The Act also started the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program.[34]

The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 provided funding to help improve building codes and outlawed the sale of incandescent light bulbs in favor of fluorescents and LEDs.[1] The act included a solar air conditioning program and funding to increase photovoltaics. The act also created the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant and set the CAFE standard to 35 mpg by 2020.

In February 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was passed, with an initial projection of $45 billion in funding levels going to energy. $11 billion went to the Weatherization Assistance Program, the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant, and the State Energy Program; $11 billion went to federal buildings and vehicles; $8 billion went to research and development programs; $2.4 billion went to new technology and facility development projects; $14 billion went to the electric grid; and $21 billion was projected to go to tax credits for renewable energy and electric vehicles, among other things.[35] Due in part to the design of the tax credits, the final amount of energy spending and incentives reached over $90 billion, leveraged $150 billion in private investment, funded 180 advanced manufacturing projects, and created more than 900,000 job-years.[36]

In December 2009, the United States Patent and Trademark Office announced the Green Patent Pilot Program.[37] The program was initiated to accelerate the examination of patent applications relating to certain green technologies, including the energy sector.[38] The pilot program was initially designed to accommodate 3,000 applications related to certain green technology categories, and the program was originally set to expire on December 8, 2010. In May 2010, the USPTO announced that it would expand the pilot program.[39]

In 2016, federal government energy-specific subsidies and support for renewables, fossil fuels, and nuclear energy amounted to $6,682 million, $489 million and $365 million, respectively.[40]

On June 1, 2017, then-President Donald Trump announced that the U.S. would cease participation in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change mitigation, agreed to under the President Barack Obama administration.[41] On November 3, 2020, incoming President Joe Biden announced that the U.S. would resume its participation.[42]

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicted that the reduction in energy consumption in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic would take many years to recover.[43] For many decades, the US imported much of its oil, but in 2020 it became a net exporter.[44]

In December 2020, Trump signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, which contained the Energy Act of 2020 and was the first major revision package to U.S. energy policy in over a decade. The bill contains increased incentives for energy efficiency (particularly in federal government buildings), improved funding for weatherization assistance, standards to phase out the use of hydrofluorocarbons, plans to rebuild the nation's energy research sector including fossil fuel research, and $7 billion in demonstration projects for carbon capture and storage.[45][46][47]

Under President Joe Biden, one-third of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve was tapped to reduce energy prices during the COVID-19 pandemic.[48] He also invoked the Defense Production Act to boost manufacturing of solar cells, renewable energy generators, fuel cells, electricity-dependent clean fuel equipment, building insulation, heat pumps, critical power grid infrastructure, and electric vehicle batteries.[49][50]

Biden also signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to invest $73 billion in the energy sector.[51] $11 billion of that amount will be invested in power grid infrastructure, with the first selected recipients for $3.46 billion announced in October 2023. This is the largest investment in the grid since the Recovery Act.[52] $6 billion will go to domestic nuclear power. From the $73 billion, the IIJA will invest $45 billion in innovation and industrial policy for key emerging technologies in energy; $430 million[53] to $21 billion in new demonstration projects at the DOE; and nearly $24 billion in onshoring, supply chain resilience, and bolstering competitive advantages in energy, divided into an $8.6 billion investment in carbon capture and storage, $3 billion in battery material reprocessing, $3 billion in battery recycling, $1 billion in rare-earth minerals stockpiling, and $8 billion in new research hubs for green hydrogen.[54] $4.7 billion will go to plugging orphan wells abandoned by oil and gas companies.[55][56][57]

In August 2022, Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act to boost DOE and National Science Foundation research activities by $174 billion.[58] He also signed the Inflation Reduction Act to create assistance programs for utility cooperatives[59] and a $27 billion green bank,[60] which includes $6 billion to lower the cost of solar power in low-income communities and $7 billion to capitalize smaller green banks.[61] The bill appropriates $270–663 billion in clean energy and energy efficiency tax credits,[62][63][64] including at least $158 billion for investments in clean energy and $36 billion for home energy upgrades from public utilities.[65][66][67] The Biden administration itself claimed that as of September 3, 2024[update], the IIJA, CaSA, and IRA together catalyzed over $910 billion in private investment (including $395 billion in electronics and semiconductors, $177 billion in electric vehicles and batteries, $167 billion in clean power, $82 billion in clean energy tech manufacturing and infrastructure, and $47 billion in heavy industry) and over $582.8 billion in public infrastructure spending (including $78.6 billion in energy aside from tax credits in the IRA).[68][needs update]

Even so, the Biden administration also presided over record high oil and gas production, reaching averages of 12.9 million barrels per day nationwide in 2023,[69] and 530,000 barrels per day from public lands since 2020 (despite a campaign pledge to halt drilling on said lands). However, growth has been driven more by Permian Basin drilling than by the administration's policies.[70]

Around spring 2024, the Biden administration announced several changes to its energy policy approach. First, the EPA issued new tailpipe emissions limits that it projected would cut emissions by 7 billion metric tons, or 56% of 2026 levels, by 2032.[71] Second, it raised royalty rates from 12.5% to 16.7%, doubled rents and increased lease bond minimums by a factor of 15 on federal lands for oil and gas companies.[72] Third, the EPA finalized new standards for power plant carbon emissions, projecting cuts of 65,000 tons by 2028 and 1.38 billion tons by 2047.[73] Fourth, the DOE announced that it would assume the role of default lead agency on permitting approvals for most new power transmission projects, as well as enact a two-year deadline, require only one environmental impact statement per project, and increase transparency around the permitting process.[74] Lastly, it issued a new rule to make large water heaters much more energy-efficient by 2029, cutting carbon emissions by a projected 332 million tons over 30 years, as part of the DOE's overall effort since 2020 to drive 2.5 billion tons in 30-year appliance emissions cuts.[75][76]

Department of Energy

editThe Energy Department's mission statement is "to ensure America's security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions."[77]

As of January 2023[update], its elaboration of the mission statement is as follows:

- "Catalyze timely, material, and efficient transformation of the nation's energy system and secure US leadership in clean energy technologies.

- "Maintain a vibrant US effort in science and engineering as a cornerstone of our economic prosperity with clear leadership in strategic areas.

- "Enhance nuclear security through defense, nonproliferation, and environmental efforts.

- "Establish an operational and adaptable framework that combines the best wisdom of all Department stakeholders to maximize mission success."[77]

Import policies

editPetroleum

editThe US bans energy imports from countries such as Russia (because of the Russo-Ukrainian War)[78] and Venezuela.[79] The US also limits exports of oil from Iran.[80] Although it is a net exporter, the US imports energy from multiple countries, led by Canada.

Clean technology

editThis section needs expansion with: a comprehensive history of clean technology import policy in the US. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

In May 2024, the Biden administration doubled tariffs on solar cells imported from China and more than tripled tariffs on lithium-ion electric vehicle batteries imported from China.[81] The increased tariffs will be phased in over a period of three years.[81]

Export

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) |

In 1975, the United States implemented a crude oil export ban, which limited most exports to other countries. It came two years after an OPEC oil embargo banned oil sales to the U.S. and sent gas prices skyrocketing. Newspaper photographs of long car lines outside of gas stations became a common and worrisome image.[82] Forty years later in 2015, Congress voted to repeal its ban on exporting U.S. crude oil. Since that year, crude exports have skyrocketed nearly 600% to 3.2 million barrels per day in 2020, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.[83]

Under President Biden, the pattern continued, as hundreds of other new oil and gas projects, many of them marked for boosting exports to counter China and Russia's influence, were approved.[84][85] In response to criticism from environmentalists, Biden temporarily suspended regulatory approvals for new natural gas export terminals in January 2024,[86] but in July, Louisiana federal judge James D. Cain Jr. halted the suspension temporarily amid a lawsuit from 16 Republican-governed states.[87]

Strategic petroleum reserve

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) |

The United States Strategic Petroleum Reserve stores as much as 600M barrels of oil.[48][needs update]

Energy consumption

editIndustry has long been the country's largest energy sector.[88][89] It used 33% of total energy in 2021, most of which was divided evenly between natural gas, electricity and petroleum. A survey from 2018 estimated that the largest energy users were the chemical industry (30%), petroleum and coal processing (18%), mining (9%) and paper (9%).[90]

The most energy-intensive industry was by far petroleum and coal, at over 30 billion BTU per employee. The paper industry was second at 6.5 billion BTU per employee. Each of these handles energy sources as part of their raw materials (fossil fuels and wood).[91] The same survey found that half of the electric use was to drive machines and about 10% each for heating, cooling and electro-chemical processes. Most of the remainder was for factory lighting and HVAC. About half of the natural gas was for process heating, and most of the rest was for boilers.[92]

Transportation used 28% of energy, almost all of which was petroleum and other fuels. Half of the combustible fuels that make up the transportation sector were gasoline, and half of the vehicle usage was for cars and small trucks.[93] Diesel and heavier trucks each made up about a quarter of their respective categories; jet fuel and aircraft were about a tenth each. Biofuels such as ethanol and biodiesel made up 5%, while natural gas was 4%. Electricity from mass transit was 0.2%; electricity for light passenger vehicles is counted in other sectors, but figures from the US Department of Energy estimate that 2.1 million electric vehicles used 6.1 TWh to travel 19 billion miles, indicating an average fuel efficiency of 3.1 miles per kWh.[94]

Over two-thirds of the energy used by homes, offices, and other commercial businesses is electric, including electric losses.[95][96] Most of the energy used in homes was for space heating (34%) and water heating (19%), much more than the amount used for space cooling (16%) and refrigeration (7%).[97] Businesses use similar percentages for space cooling and refrigeration. They use less for space and water heating but more for lighting and cooking.[98]

Most homes in the US are single-family detached,[99] which on average use almost triple the energy of apartments in larger buildings.[100] However, single family households have 50% more persons and triple the floor space. Usage per square foot of living space is roughly equal for most housing types except small apartment buildings and mobile homes. Small apartments are more likely to be older than other housing types,[101] while mobile homes tend to have poor insulation.[102]Sources

editIn 2021, energy in the United States came mostly from fossil fuels: 36% originated from petroleum, 32% from natural gas, and 11% from coal.[103] Renewable energy supplied the rest: hydropower, biomass, wind, geothermal, and solar supplied 12%, while nuclear supplied 8%.[103]

Utilities

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) |

In the U.S., utilities are regulated at the federal level by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. In each state, a public utility commission (PUC) regulates electricity, gas, and other forms of power.[105]

States began deregulating electricity systems in the 1990s as a way to promote competition and lower costs. While transmission lines and distribution services are still provided by local utility companies, wholesale markets were created to enable power plant investments and allow utilities to acquire power for customers. Those wholesale markets are operated by regional transmission organizations (RTOs).[106]

Deregulation led to the creation of independent energy suppliers and allowed customers to choose their electric supplier.

Energy efficiency

editOpportunities for increased energy efficiency are available across the economy, including buildings/appliances, transportation, and manufacturing. Some opportunities require new technology. Others require behavioral change by individuals or at the community level or above.

The U.S. federal government has initiated various energy-efficiency policies, programs and legislation, including the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), CAFE standards for vehicle fuel efficiency, and the Energy Star program for promoting efficiency in household appliances. American governments, at all levels, have implemented various building standards to improve energy efficiency.[107]

Building-related energy efficiency innovation takes many forms, including improvements in water heaters; refrigerators and freezers; building control technologies for heating, ventilation, and cooling (HVAC); adaptive windows; building codes; and lighting.[108]

Energy-efficient technologies can enable superior performance. For example, this could include higher quality lighting, heating and cooling with greater controls, or improved reliability of service through greater ability of utilities to respond to time of peak demand.[108]

More efficient vehicles save on fuel purchases, emit fewer pollutants, improve health and save on medical costs.[108]

Heat engines are only 20% efficient at converting oil into work.[109][110] However, heat pumps are highly efficient, up to 300% in some cases, at moving heat to and from outside air.[111]

Energy budget, initiatives and incentives

editMost energy policy incentives are financial. Examples of these include tax breaks, tax reductions, tax exemptions, rebates, loans and subsidies.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, and the Inflation Reduction Act all provided such incentives.

Tax incentives

editThe US Production Tax Credit (PTC) reduces the federal income taxes of qualified owners of renewable energy projects based on grid-connected output. The Investment Tax Credit (ITC) reduces federal income taxes for qualified tax-payers based on capital investment in renewable energy projects. The Advanced Energy Manufacturing Tax Credit (MTC) awards tax credits to selected domestic manufacturing facilities that support clean energy development.[112]

Loan guarantees

editThe Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program guarantees financing up to 80% of a qualifying project's cost.[34]

Renewable energy

editIn the United States, the share of renewable energy in electricity generation has grown to 21% by 2020.[113] Oil use is expected to decline in the US because of increasing vehicle efficiency and replacement of crude oil by natural gas as a feedstock for the petrochemical sector. One forecast is that the rapid uptake of electric vehicles will reduce oil demand drastically by 80% lower in 2050 compared with today.[114]

A Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) is a state/local mandate that requires electricity providers to supply a minimum amount of power from renewable sources, usually defined as a percentage of total energy production.[115]

Biofuels

editThe federal government offers many programs to support the development and implementation of biofuel-based replacements for fossil fuels.[116]

Landowners and operators who establish, produce, and deliver biofuel crops may qualify for partial reimbursement of startup costs as well as for annual payments.[116] Loan guarantees help finance development, construction, and retrofitting of commercial-scale biorefineries. Grants help build demonstration-scale biorefineries and also help scale up existing biorefineries. Loan guarantees and grants support the purchase of pumps that dispense ethanol-including fuels.[116]

Production support helps makers expand output.[116] Tax credits support the purchase of fueling equipment (gas pumps) for specific fuels including some biofuels.[116]

Education grants support training the public about biodiesel.[116] Research, development, and demonstration grants support feedstock development and biofuel development.[116] Grants support research, demonstration, and deployment projects to replace buses and other petroleum-fueled vehicles with biofuel or other alternative fuel-based vehicles in addition to necessary fueling infrastructure.[116]

Producer subsidies

editThe 2005 Energy Policy Act offered incentives including billions in tax reductions for nuclear power, fossil fuel production, clean coal technologies, renewable electricity, and conservation and efficiency improvements.[117]

Federal leases

editThe US leases federal land to private firms for energy production. The volume of leases has varied by presidential administration. During the first 19 months of the Joe Biden administration, 130,000 acres were leased, compared to 4 million under the Donald Trump administration, 7 million under the Obama administration, and 13 million under the George W. Bush administration.[118]

The Inflation Reduction Act requires that for federal lands, oil and gas auctions be carried out before wind and solar lease consideration, even as the Act brought about royalty rate increases.[119] Permian Basin drilling activity, some of it on federal lands, also brought about record high oil production even after the Act's signing in 2022.[70]

Net metering

editNet metering is a policy by many states in the United States designed to help the adoption of renewable energy. Net metering was pioneered in the United States as a way to allow solar and wind to provide electricity whenever available and allow use of that electricity whenever it was needed, beginning with utilities in Idaho in 1980, and in Arizona in 1981.[120] In 1983, Minnesota passed the first state net metering law.[121] As of March 2015, 44 states and Washington, D.C. have developed mandatory net metering rules for at least some utilities.[122] However, although the states' rules are clear, few utilities actually compensate at full retail rates.[123]

Net metering policies are determined by states, which have set policies varying on a number of key dimensions. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 required state electricity regulators to "consider" (but not necessarily implement) rules that mandate public electric utilities make net metering available to their customers upon request.[124] Several legislative bills have been proposed to institute a federal standard limit on net metering. They range from H.R. 729, which sets a net metering cap at 2% of forecasted aggregate customer peak demand, to H.R. 1945, which has no aggregate cap, but does limit residential users to 10 kW, a low limit compared to many states, such as New Mexico, with an 80,000 kW limit, or states such as Arizona, Colorado, New Jersey, and Ohio, which limit as a percentage of load.[125]Electricity transmission and distribution

editElectric power transmission results in energy loss, through electrical resistance, heat generation, electromagnetic induction and less-than-perfect electrical insulation.[126] Electric transmission (production to consumer) loses over 23% of the energy due to generation, transmission, and distribution.[127] In 1995, long distance transmission losses were estimated at 7.2% of the power transported.[128] Reducing transmission distances reduces these losses. For every five units of energy going into typical large fossil fuel power plants, only about one unit reaches the consumer in a usable form.[129]

A similar situation exists in natural gas transport, which requires compressor stations along pipelines that use energy to keep the gas moving. Gas liquefaction, cooling, and re-gasification in the liquified natural gas supply chain uses a substantial amount of energy.

Distributed generation and distributed storage are means of reducing total and transmission losses as well as reducing costs for electricity consumers.[130][131][132]

In October 2023, the Biden administration announced the largest major investment in the grid since the Recovery Act in 2009.[133][134]

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is the primary regulatory agency of electric power transmission and wholesale electricity sales within the United States. FERC was originally established by Congress in 1920 as the Federal Power Commission and has since undergone multiple name and responsibility modifications. Electric power distribution and the retail sale of power is under state jurisdiction.

Order No. 888

editOrder No. 888 was adopted by FERC on April 24, 1996. It was "designed to remove impediments to competition in the wholesale bulk power marketplace and to bring more efficient, lower cost power to the Nation's electricity consumers. The legal and policy cornerstone of these rules is to remedy undue discrimination in access to the monopoly owned transmission wires that control whether and to whom electricity can be transported in interstate commerce."[135] The Order required all public utilities that own, control, or operate facilities used for transmitting electric energy in interstate commerce, to have open-access non-discriminatory transmission tariffs. These tariffs allow any electricity generator to utilize existing power lines to transmit the power that they generate. The Order also permits public utilities to recover the costs associated with providing their power lines as an open-access service.[135]

Energy Policy Act of 2005

editThe Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct) expanded federal authority to regulate power transmission. EPAct gave FERC significant new responsibilities, including enforcement of electric transmission reliability standards and the establishment of rate incentives to encourage investment in electricity transmission.[136]

Historically, local governments exercised authority over the grid and maintained significant disincentives for actions that would benefit other states. Localities with cheap electricity have a disincentive for making interstate commerce in electricity trading easier, since other regions would be able to compete for that energy and drive up rates. For example, some regulators in Maine refused to address congestion problems because the congestion protects Maine rates.[137]

Local constituencies can block or slow permitting by pointing to visual impacts, as well as to environmental and health concerns. In the US, generation is growing four times faster than transmission, but transmission upgrades require the coordination of multiple jurisdictions, complex permitting, and cooperation between the many companies that collectively own the grid. The US national security interest in improving transmission was reflected in the EPAct, which gave the Department of Energy the authority to approve transmission if states refused to act.[138]

Order No. 1000

editIn 2010, FERC issued Order 1000, which required RTOs to create regional transmission plans and identify transmission needs based on public policy. Cost allocation reforms were included, possibly to reduce barriers faced by non-incumbent transmission developers.[139]

Order No. 841

editIn February 2018, FERC issued Order 841, which required wholesale markets to open up to individual storage installations, regardless of interconnection point (transmission, distribution or behind-the-meter).[140][141] The Order was challenged in court by the state public utility commissions via the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC), the American Public Power Association, and others who claimed that FERC overstepped its jurisdiction by regulating how local electric distribution and behind-the-meter facilities are administered, i.e., by not providing an opt-out of wholesale market access for energy storage facilities located at the distribution level or behind-the-meter. The D.C. Circuit Court issued an order in July 2020 that upheld Order 841 and dismissed the petitioners' complaints.[142][143][144]

Order No. 2222

editFERC issued Order 2222 on September 17, 2020, enabling distributed energy resources such as batteries and demand response to participate in regional wholesale electricity markets.[145][146] Market operators submitted initial compliance plans by early 2022.[147] The Supreme Court had ruled in 2016 in FERC v. Electric Power Supply Ass'n that the agency had the authority to regulate demand response transactions.[148]

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

edit$11 billion of the $73 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will be invested in the electrical grid's adjustment to renewable energy, with some of the money going to new loans for electric power transmission lines and required studies for future transmission needs.[149][150][151]

On October 24, 2023, the administration announced that the first $3.46 billion in grants from the Act's $11 billion grid rebuilding authorization would go to 58 projects in 44 states. 16 projects are categorized as improving grid resilience, 34 are categorized as building smart grids, and eight are categorized as pursuing grid innovation. The investment is the largest in the American grid since the Recovery Act 14 years earlier. According to Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, the projects could enable 35 gigawatts of renewable energy to come online by 2030 and 400 microgrids to be built.[133][134] On August 6, 2024, the DOE announced the recipients of the next $2.2 billion in GRIP grants, eight grid innovation projects across 18 states adding a total of 13 gigawatts of capacity to the grid.[152]

On October 30, the DOE announced the results of a mandated triennial study that, for the first time in its history, included anticipation of future grid transmission needs; the Act had explicitly required this inclusion. The study found a decline in infrastructure investments since 2015 and consistently high prices in the Rust Belt and California since 2018. The study projected a 20 to 128 percent increase in transmission would be needed within regions, while interregional transmission would need to increase by 25 to 412 percent. The study found that the most potential was in better connecting Texas to the Southwest region, the Mississippi Delta and Midwest regions to the Great Plains region, and New York to New England.[150][153][149]

The DOE also announced the first three recipients of a new $2.5 billion loan program called the Transmission Facilitation Program (TFP), created to provide funding to help build up the interstate power grid. They are the 1.2-gigawatt Twin States Clean Energy Link between Quebec, New Hampshire and Vermont; the 1.5-gigawatt Cross-Tie Transmission Line between Utah and Nevada; and the 1-gigawatt Southline Transmission Project between Arizona and New Mexico.[151][149] The following April 25, the DOE announced the TFP selection of the 2-gigawatt Southwest Intertie Project North, which effectively extends the One Nevada Transmission Line northward to Idaho.[154] The next October, the DOE announced that four projects, the 1.2-gigawatt Aroostook Project in Maine, 1.9-gigawatt Cimarron Link in Oklahoma, 3-gigawatt Southern Spirit between Texas and Mississippi, and 1-gigawatt Southline in New Mexico, were being awarded a total of $1.5 billion under the TFP; the DOE also released its first ever National Transmission Planning Study to follow up on the Needs Study, forecasting a needed national transmission capacity increase of 2.4 to 3.5 times the 2020 level by 2050 to keep costs low and facilitate the energy transmission, with estimated cost savings ranging from $270 billion to $490 billion.[155]

Inflation Reduction Act

editThe Inflation Reduction Act of the Biden administration has fast-tracked transmission projects by helping purchase $30 billion in wholesale electric transmission contracts, as well as by publishing a national transmission needs report, which had been expanded in scope by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[156] The Act provides $760 million to states, tribes and localities to accelerate planning approvals for high-voltage interstate transmission lines; the first $371 million was awarded on July 24, 2024.[157]

Even with the IRA, U.S. transmission grid capacity would have to triple in order to meet the global target of net zero carbon emissions according to a Princeton University study.[158][159]

Order No. 2023

editOn July 28, 2023, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved Order No. 2023, which regulates the interconnection process that ties renewables projects into the large-scale grid. Among other provisions, the rule requires transmission planners to consolidate projects into 'clusters' for regulatory approval purposes on a 'first-ready, first-served' basis that prioritizes the most well-studied and fully financed projects. It also requires transmission planners to forecast advanced technologies and allow for multiple projects to share a new single interconnection point. It "imposes firm deadlines and penalties if transmission providers fail to complete interconnection studies on time".[160]

Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorizations and Permits; NEPA reform

editThe Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 required the federal government to implement a two-year deadline for permitting approvals for energy projects, including grid transmission, and also to designate a lead agency for such projects.

On April 25, 2024, the DOE finalized a rule to implement the requirement. The rule, called Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorizations and Permits, stated the DOE would assume the role of default lead agency for most new power transmission projects. The rule also stated that the DOE would streamline permitting approvals, require only one environmental impact statement per project, and increase transparency around the permitting process.[74]

On the same day, the DOE authorized changes to its categorical exclusion process under the National Environmental Policy Act, allowing faster permit reviews for grid battery storage, flywheel storage, reconductoring and advanced power flow control, and midsize solar PV projects.[161]

Order Nos. 1920 and 1977

editOn May 13, 2024, FERC issued Order Nos. 1920 and 1977. The former order requires utilities to plan 20 years in advance to anticipate future regional (though not interregional) transmission needs, with five-year updates, and to cooperate in creating a default cost-sharing plan to deliver to state regulators. It "provides for cost-effective expansion of transmission that is being replaced, when needed, known as 'right-sizing' transmission facilities", and it allows states more opportunities to cooperate with utility companies and energy project developers, while preventing states that benefit from regional transmission projects from not paying for them.[162][163][164]

The latter order affirms FERC's siting authority in National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors if a state regulatory agency denies any of its own siting responsibility thereof, thus implementing part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The order creates an Applicant Code of Conduct to encourage proper landowner outreach and adds air quality, environmental justice and tribal engagement reports to the list of requirements for project applicants.[165]

Greenhouse gas emissions

editWhile the United States has cumulatively emitted the most greenhouse gases of any country, it represents a declining fraction of ongoing emissions, long superseded by China.[167][168] Since its peak in 1973, per capita US emissions have declined by 40%, resulting from improved technology, the shift in economic activity from manufacturing to services, changing consumer preferences and government policy.[169]

State and local government have launched initiatives. Cities in 50 states endorsed the Kyoto protocol.[170] Northeastern US states established the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI),[171] a state-level emissions cap and trade program.

On February 16, 2007, the United States, together with leaders from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, United Kingdom, Brazil, China, India, Mexico and South Africa agreed in principle on the outline of a successor to the Kyoto Protocol known as the Washington Declaration. They envisaged a global cap-and-trade system that would apply to both industrialized nations and developing countries.[172][173] The system did not come to pass.

Arjun Makhijani argued that in order to limit global warming to 2 °C, the world would need to reduce CO2 emissions by 85% and the US by 95%.[174][175][176] He developed a model by which such changes could occur. Effective delivered energy is modeled to increase from about 75 quadrillion BTU in 2005 to about 125 quadrillion in 2050,[177] but due to efficiency increases, the actual energy input increases from about 99 quadrillion BTU in 2005 to about 103 quadrillion in 2010 and then will decrease to about 77 quadrillion in 2050.[178] Petroleum use is assumed to increase until 2010 and then linearly decrease to zero by 2050. The roadmap calls for nuclear power to decrease to zero, with the reduction also beginning in 2010.[179]

Joseph Romm called for the rapid deployment of existing technologies to decrease carbon emissions. He argued that "If we are to have confidence in our ability to stabilize carbon dioxide levels below 450 p.p.m. emissions must average less than [5 billion metric tons of carbon] per year over the century. This means accelerating the deployment of the 11 wedges so they begin to take effect in 2015 and are completely operational in much less time than originally modeled by Socolow and Pacala."[180]

In 2012, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory assessed the technical potential for renewable electricity for each of the 50 states. It concluded that each state had the technical potential for renewable electricity, mostly from solar and wind, that could exceed its current electricity consumption. The report cautions: "Note that as a technical potential, rather than economic or market potential, these estimates do not consider availability of transmission infrastructure, costs, reliability or time-of-dispatch, current or future electricity loads, or relevant policies."[181]

In 2022, the EPA received funding for a green bank called the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund to drive down carbon dioxide emissions, as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, the largest decarbonization incentives package in U.S. history.[60][61] The Fund will award $14 billion to a select few green banks nationwide for a broad variety of decarbonization investments, $6 billion to green banks in low-income and historically disadvantaged communities for similar investments, and $7 billion to state and local energy funds for decentralized solar power in communities with no financing alternatives.[182][183] The EPA set the deadline to apply for the first two award initiatives at October 12, 2023[184] and the latter initiative at September 26, 2023.[185]

See also

edit- United States hydrogen policy

- 2000s energy crisis

- Carbon tax

- Carter Doctrine

- Climate change policy of the United States

- Economics of new nuclear power plants

- Electricity sector of the United States

- Emissions trading

- Energy and American Society: Thirteen Myths

- Energy in the United States

- Energy law

- Energy policy of the Obama administration

- Energy policy of the Soviet Union

- List of United States energy acts

- List of U.S. states by electricity production from renewable sources

- United States House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming

- United States House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis

- United States Secretary of Energy

- World energy consumption

References

edit- ^ a b "Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (Enrolled as Agreed to or Passed by Both House and Senate)". Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency". Dsireusa.org. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Grossman, Peter (2013). U.S. Energy Policy and the Pursuit of Failure. Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-1107005174.

- ^ Hamilton, Michael S. 2013. Energy Policy Analysis: A Conceptual Framework. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

- ^ "SEI: Energy Consumption". Solarenergy.org. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Grant (July 4, 2014). "U.S. is now world's biggest oil producer". www.chicagotribune.com. Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ "EIA: U.S. Net Oil Imports to Drop to Lowest Levels in 60 Years". Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ "BP Statistical Review 2018" (PDF). Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Will Soon Export More Oil, Liquids Than Saudi Arabia". Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Is Now Largest Oil... And Gas Producer In The World". Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "Is U.S. Energy Dominance Coming To An End?". Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Oil producers agree to cut production by a tenth". BBC News. April 9, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Energy in the United States: 1635–2000 – Electricity". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ "Natural Gas". Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ "Oil and natural gas depletion and our future". Archived from the original on February 9, 2008.

- ^ Vivian, John. "Wood and Coal Stove Advisory". Motherearthnews.com. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Painter, David S. (1986). Oil and the American Century: The Political Economy of US Foreign Oil Policy, 1941–1954. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-82693-1.

- ^ "Petroleum Timeline". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ "Energy in the United States: 1635–2000 – Coal". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ a b "Energy in the United States: 1635–2000 – Total Energy". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ "Energy in the United States: 1635–2000 – Petroleum". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ "Niagara Falls History of Power". Niagarafrontier.com. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Energy in the United States: 1635–2000 – Renewable". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ^ "Performance Profiles of Major Energy Producers 1993" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2001. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

See page 48.

- ^ "Weatherization Assistance Program". Eere.energy.gov. January 30, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Communities of the Future" (PDF). Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Relyea, Harold; Carr, Thomas P. (2003). The Executive Branch, Creation and Reorganization. Nova Publishers. p. 29.

- ^ Pub. L. 96–294

- ^ Pub. L. 111–67 (text) (PDF)

- ^ 50 U.S.C. § 4502

- ^ "Estimating U.S. Government Subsidies to Energy Sources: 2002–2008" (PDF). Environmental Law Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2013.

- ^ Erwin, Jerry (October 9, 2006). "The Challenges Facing the Intelligence Community Regarding Global Oil Depletion". Portland Peak Oil. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- ^ "Summary of the Energy Policy Act". EPA.gov. February 22, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b U.S. Renewable Energy Quarterly Report, October 2010 Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine American Council On Renewable Energy

- ^ Fred Sissine, Anthony Andrews, Peter Folger, Stan Mark Kaplan, Daniel Morgan, Brent D. Yacobucci (March 12, 2009). Energy Provisions in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Report). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FACT SHEET: The Recovery Act Made The Largest Single Investment In Clean Energy In History, Driving The Deployment Of Clean Energy, Promoting Energy Efficiency, And Supporting Manufacturing". whitehouse.gov. February 25, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ "USPTO Expands Green Technology Pilot Program to More Inventions". United States Patent and Trademark Office. May 21, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Emerging Energy and Intellectual Property – The Often Unappreciated Risks and Hurdles of Government Regulations and Standard Setting Organizations". The National Law Review. Husch Blackwell. May 22, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "USPTO Extends Deadline to Participate in Green Technology Pilot Program by One Year". United States Patent and Trademark Office. November 10, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ This article incorporates public domain material from Direct Federal Financial Interventions and Subsidies in Energy in Fiscal Year 2016. United States Department of Energy.

- ^ Beavers, Olivia (June 1, 2017). "Pro-Paris agreement protesters flock to White House". The Hill. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Parsons, Jeff (January 21, 2020). "United States rejoins Paris climate agreement as Biden signs executive order". Metro. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Annual Energy Outlook 2021" (PDF). Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Oil imports and exports - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ "ICYMI: What They're Saying About the Energy Act of 2020". U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. December 29, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Bresette, Daniel (December 22, 2020). "The Energy Act of 2020 is a Step in the Right Direction, But More Comprehensive Climate Action is Still Needed - Press Release". EESI. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Energy Act of 2020 (CCUS provisions) – Policies". IEA. March 10, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "DOE Announces Notice of Sale of Additional Crude Oil From the Strategic Petroleum Reserve". Energy.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ "President Biden Invokes Defense Production Act to Accelerate Domestic Manufacturing of Clean Energy". Energy.gov. June 6, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ The White House (June 6, 2022). "FACT SHEET: President Biden Takes Bold Executive Action to Spur Domestic Clean Energy Manufacturing". The White House. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Sprunt, Barbara (August 10, 2021). "Here's What's Included In The Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill". NPR. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ "Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) Program". Energy.gov. October 24, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Announces $6 Billion To Drastically Reduce Industrial Emissions and Create Healthier Communities". Energy.gov. March 8, 2023. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ Higman, Morgan (August 18, 2021). "The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Will Do More to Reach 2050 Climate Targets than Those of 2030". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ "Interior Department Releases Implementation Guidance to States on Infrastructure Law Efforts to Address Legacy Pollution". U.S. Department of the Interior. December 17, 2021. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Bertrand, Savannah (August 12, 2021). "Plugging Orphaned Oil and Gas Wells Provides Climate and Jobs Benefits - Article". EESI. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Hoffman, Elisia; Jurich, Kirsten; Argento-McCurdy, Hannah; Chyung, Chris; Ricketts, Sam (November 18, 2022). "How States Can Lead on Reducing Harms From Methane". Center for American Progress. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Shivakumar, Sujai; Arcuri, Gregory; Uno, Hideki; Glanz, Benjamin (August 11, 2022). "A Look at the Science-Related Portions of CHIPS+". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Lechleitner, Liz (August 23, 2022). "Electric and agricultural co-op leaders respond to passage of Inflation Reduction Act". NCBA CLUSA. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Harris, Lee (January 19, 2023). "Green Capital Feuds With Local Lenders Over National Climate Bank". The American Prospect. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "Biden-Harris Administration Seeks Public Input on Inflation Reduction Act's Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund". US EPA. October 21, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Gardner, Timothy; Shepardson, David (October 5, 2022). "U.S. seeks input on climate law's $270 billion in tax breaks". Reuters. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ "CBO Scores IRA with $238 Billion of Deficit Reduction". Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. September 7, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ McBride, William; Bunn, Daniel (June 7, 2023). "Repealing Inflation Reduction Act's Energy Credits Would Raise $663 Billion, JCT Projects". Tax Foundation. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ The Inflation Reduction Act Drives Significant Emissions Reductions and Positions America to Reach Our Climate Goals (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Energy Office of Policy. August 2022.

- ^ Green, Hank (August 12, 2022). The Biggest Climate Bill of Your Life - But What does it DO? (YouTube video). Missoula, Montana: Vlogbrothers. Event occurs at 10 minutes 50 seconds. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ "Summary: The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022" (PDF). Senate Democratic Leadership. August 11, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022. Estimates from the United States Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation or Congressional Budget Office, depending on the number.

- ^ "Investing In America". The White House. September 3, 2024. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ "United States produces more crude oil than any country, ever". Homepage - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Richards, Heather (May 13, 2024). "What Biden's oil record means for the industry's future". E&E News by POLITICO. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Daly, Matthew; Krisher, Tom (March 20, 2024). "EPA issues new auto rules aimed at cutting carbon emissions, boosting electric vehicles and hybrids". AP News. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Groom, Nichola (April 12, 2024). "US finalizes higher fees for oil and gas companies on federal lands". Reuters. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Suite of Standards to Reduce Pollution from Fossil Fuel-Fired Power Plants". US EPA. April 24, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Biden-Harris Administration Announces Final Transmission Permitting Rule and Latest Investments To Accelerate the Build Out of a Resilient, Reliable, Modernized Electric Grid". Energy.gov. April 25, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ 89 CFR 37778

- ^ "DOE Finalizes Efficiency Standards for Water Heaters to Save Americans Over $7 Billion on Household Utility Bills Annually". Energy.gov. April 30, 2024. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Mission". Energy.gov. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ House, The White (March 8, 2022). "FACT SHEET: United States Bans Imports of Russian Oil, Liquefied Natural Gas, and Coal". The White House. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ "Weekly U.S. Imports from Venezuela of Crude Oil (Thousand Barrels per Day)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Wallace, Paul (June 5, 2022). "US May Allow More Iran Oil to Flow Even Without Deal, Says Vitol". Bloomberg. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Boak, Josh; Hussein, Fatima; Wiseman, Paul; Tang, Didi (May 14, 2024). "Biden hikes tariffs on Chinese EVs, solar cells, steel, aluminum — and snipes at Trump". AP News. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Egan, Matt (January 29, 2016). "After 40-year ban, U.S. starts exporting crude oil". CNNMoney. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Kelly, Stephanie; Renshaw, Jarrett; Kelly, Stephanie (December 9, 2021). "White House not weighing oil export ban, source says, as lawmakers urge higher domestic ouput [sic]". Reuters. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Bearak, Max (April 6, 2023). "It's Not Just Willow: Oil and Gas Projects Are Back in a Big Way". The New York Times. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Editorial Board (January 29, 2024). "Biden's LNG decision is a win for political symbolism, not the climate". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (February 7, 2024). "Joe Biden just did the rarest thing in US politics: he stood up to the oil industry". the Guardian. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ The Associated Press (July 2, 2024). "A judge sides with states over Biden and allows gas export projects to move forward". NPR. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ "Monthly Energy Review". EIA. April 25, 2023. 2.1a Energy consumption: Residential, commercial, and industrial sectors. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Energy Review". EIA. April 25, 2023. 2.1b Energy consumption: Transportation sector, total end-use sectors, and electric power sector. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Energy use in industry". EIA. June 13, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "2018 MECS Survey Data". EIA. August 27, 2021. Table 6.1 By Manufacturing Industry and Region. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "2018 MECS Survey Data". EIA. August 27, 2021. Table 5.4 By Manufacturing Industry with Total Consumption of Electricity. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Energy use for transportation". EIA. June 28, 2022. 1.1 Primary energy overview. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "US: In 2021, Plug-Ins Traveled 19 Billion Miles On Electricity". InsideEVs. November 29, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Energy Review". EIA. April 25, 2023. 2.2 Residential sector energy consumption. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Monthly Energy Review". EIA. April 25, 2023. 2.3 Commercial sector energy consumption. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ Assuming electric losses of about 65%. "Energy use in homes". EIA. June 14, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ Assuming ventilation is roughly proportional for heating and cooling. "2018 CBECS Survey Data". EIA. December 21, 2022. End-use consumption. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Table HC9.1 Household demographics of U.S. homes by housing unit type, 2015". EIA. May 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "2015 RECS Survey Data". EIA. May 2018. CE1.1 Summary consumption and expenditures in the U.S. - totals and intensities. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Table HC2.3 Structural and geographic characteristics of U.S. homes by year of construction, 2015". EIA. May 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Table HC2.1 Structural and geographic characteristics of U.S. homes by housing unit type, 2015". EIA. May 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "U.S. energy facts explained - consumption and production - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ "Visualizing America's Energy Use, in One Giant Chart". Visual Capitalist. May 6, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ An Overview of PUC s for State Environment and Energy Officials. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- ^ "US Electricity Markets 101". Resources for the Future. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Doris, Elizabeth; Jaquelin Cochran; and Martin Vorum: Energy Efficiency Policy in the United States: Overview of Trends at Different Levels of Government Technical Report NREL/TP-6A2-46532, December 2009, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, U.S. Dept. of Energy, retrieved August 18, 2024

- ^ a b c "Opportunities for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions" (PDF). Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Improving IC Engine Efficiency". Courses.washington.edu. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Carnot Cycle". Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "In-depth guide to heat pumps". Energy Saving Trust. June 4, 2024. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ The Bottom Line on Renewable Energy Tax Credits. World Resources Institute

- ^ "Renewables became the second-most prevalent U.S. electricity source in 2020 - Today in Energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "DNV GL's Energy Transition Outlook 2018". eto.dnvgl.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ U.S. Renewable Energy Quarterly Report Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine American Council on Renewable Energy, October 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Alternative Fuels Data Center: Ethanol Laws and Incentives in Federal". afdc.energy.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ Energy Policy Act of 2005

- ^ DeBarros, Timothy Puko and Anthony (September 4, 2022). "Federal Oil Leases Slow to a Trickle Under Biden". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Hart, Sarah (March 24, 2023). "Potential Impacts of the IRA's Onshore Energy Leasing Provisions". Harvard Law School - Environmental & Energy Law Program. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Current Experience With Net Metering Programs (1998)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "Minnesota". Dsireusa.org. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "Net Metering" (PDF). ncsolarcen-prod.s3.amazonaws.com. North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center. March 1, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ Schelly, Chelsea; et al. (2017). "Examining interconnection and net metering policy for distributed generation in the United States". Renewable Energy Focus. 22–23: 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.ref.2017.09.002.

- ^ "Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA)". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ "Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency". North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ "Transmission and distribution technologies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Preston, John L. (October 1994). "Comparability of Supply- and Consumption-Derived Estimates of Manufacturing Energy Consumption" (PDF). US Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

Table 7: Total energy: 29,568.0 trillion Btu, Loss: 7,014.1 trillion Btu

- ^ "Technology Options for the Near and Long Term" (PDF). US Climate Change Technology Program. August 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "Electric System Losses to Inefficiency" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Power To The People! Michigan Tech Researchers Say Distributed Renewables Save Utility Customers Money". CleanTechnica. March 20, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ Prehoda, Emily; Pearce, Joshua M.; Schelly, Chelsea (2019). "Policies to Overcome Barriers for Renewable Energy Distributed Generation: A Case Study of Utility Structure and Regulatory Regimes in Michigan". Energies. 12 (4): 674. doi:10.3390/en12040674.

- ^ Gil, Hugo A.; Joos, Geza (2008). "Models for Quantifying the Economic Benefits of Distributed Generation". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. 23 (2): 327–335. Bibcode:2008ITPSy..23..327G. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2008.920718. ISSN 0885-8950. S2CID 35217322.

- ^ a b St. John, Jeff (October 18, 2023). "The US just made its biggest-ever investment in the grid". Canary Media. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) Program". Energy.gov. October 24, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Order No. 888: Promoting Wholesale Competition Through Open Access Non-discriminatory Transmission Services by Public Utilities; Recovery of Stranded Costs by Public Utilities and Transmitting Utilities". FERC. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024.

- ^ Energy Policy Act of 2005 Fact Sheet (PDF). FERC Washington, D.C. August 8, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Matthew H.; Sedano, Richard P. (2004). Electricity transmission : a primer (PDF). Denver, Colorado: National Council on Electricity Policy. p. 32 (page 41 in .pdf). ISBN 1-58024-352-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 30, 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Wald, Matthew (August 27, 2008). "Wind Energy Bumps into Power Grid's Limits". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ "FERC: Industries - Order No. 1000 - Transmission Planning and Cost Allocation". Ferc.gov. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Ko, Ted (October 17, 2019). "Let's kill 'utility-' or 'grid-scale' storage". Utility Dive. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Konidena, Rao (2019). "FERC Order 841 levels the playing field for energy storage". MRS Energy & Sustainability. 6: 1–3. doi:10.1557/mre.2019.5. S2CID 182646294 – via CambridgeCore.

- ^ Jeff St. John (July 10, 2020). "'Enormous Step' for Energy Storage as Court Upholds FERC Order 841, Opening Wholesale Markets". www.greentechmedia.com. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "FERC Order 841: US about to take 'most important' step towards clean energy future". www.energy-storage.news. July 13, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Sean Baur (September 1, 2020). "Going beyond Order 841 to more meaningful FERC storage policy". Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "FERC Opens Wholesale Markets to Distributed Resources: Landmark Action Breaks Down Barriers to Emerging Technologies, Boosts Competition". FERC. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "'Game-Changer' FERC Order Opens Up Wholesale Grid Markets to Distributed Energy Resources". www.greentechmedia.com. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "FERC Order 2222: Experts offer cheers and jeers for first round of filings". Canary Media. March 14, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ FERC v. Electric Power Supply Assn., No. 14–840, 577 U. S. ____, slip op. at 2, 33–34 (2016).

- ^ a b c "Three big transmission projects win $1.3B in DOE loans". Canary Media. October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "National Transmission Needs Study". Energy.gov. October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "Transmission Facilitation Program". Energy.gov. October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Invests $2.2 Billion in the Nation's Grid to Protect Against Extreme Weather, Lower Costs, and Prepare For Growing Demand". Energy.gov. August 6, 2024. Retrieved August 6, 2024.

- ^ Boughton, Steven G.; Kiger, Miles (November 16, 2023). "Department of Energy Releases Triennial National Transmission Needs Study". Washington Energy Report. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Announces Final Transmission Permitting Rule and Latest Investments To Accelerate the Build Out of a Resilient, Reliable, Modernized Electric Grid". Energy.gov. April 25, 2024. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Invests $1.5 Billion to Bolster the Nation's Electricity Grid and Deliver Affordable Electricity to Meet New Demands". Energy.gov. October 3, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ U. S. Department of Energy. U.S. Dept. of Energy website (October 2023). National Transmission Needs Study. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Invests $371 Million in 20 Projects to Accelerate Transmission Permitting Across America". Energy.gov. July 24, 2024. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ Peter Behr. (25 December 2023). "One Southwest power project’s 17-year odyssey shows the hurdles to Biden’s climate agenda". Politico website Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ Princeton University. Net-Zero America. (29 October 2021). Final Report Summary: Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts. Princeton University website Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Explainer on the Interconnection Final Rule". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. July 28, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "DOE Reduces Regulatory Hurdles For Energy Storage, Transmission, and Solar Projects". U.S. Department of Energy. April 25, 2024. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "Docket Number RM21-17-000: Final Rule". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "Building for the Future Through Electric Regional Transmission Planning and Cost Allocation". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "Chairman Phillips' and Commissioner Clements' Joint Concurrence on FERC Order No. 1920". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "Staff Presentation: Applications for Permits to Site Interstate Electric Transmission Facilities". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ ● Source for carbon emissions data: "Territorial (MtCO₂) / Emissions / Carbon emissions / Chart View". Global Carbon Atlas. 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

● Source for country population data: "Population 2022" (PDF). World Bank. 2024. Archived from the original on October 22, 2024. - ^ Raupach, M.R. et al. (2007). "Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO2 emissions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (24): 10288–10293.

- ^ "China now no. 1 in CO2 emissions; USA in second position". Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007.

- ^ "CO₂ Data Explorer". Our World in Data. November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ "US Climate Protection Agreement Home Page". Archived from the original on September 30, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative". Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "Politicians sign new climate pact". BBC News. February 16, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Guardian Unlimited: Global leaders reach climate change agreement". London: Environment.guardian.co.uk. February 16, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Makhijani pg. 3

- ^ Makhijani, Arjun Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free, A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy 2007 ISBN 978-1-57143-173-8

- ^ Makhijani Fig. 5-5, 5-8

- ^ Makhijani Fig. 5-7

- ^ Makhijani Fig. 5-8

- ^ Makhijani Fig. 5-5

- ^ Romm, Joseph. "Cleaning up on carbon", June 19, 2008

- ^ "Renewable Energy Technical Potential". National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012., p.2.

- ^ Yañez-Barnuevo, Miguel (September 12, 2022). "New Climate Law Jumpstarts Clean Energy Financing - Article". EESI. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "About the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund". United States Environmental Protection Agency. June 5, 2023. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Launches Historic $20 Billion in Grant Competitions to Create National Clean Financing Network as Part of Investing in America Agenda". US EPA. July 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Biden-Harris Administration Launches $7 Billion Solar for All Grant Competition to Fund Residential Solar Programs that Lower Energy Costs for Families and Advance Environmental Justice Through Investing in America Agenda". US EPA. June 28, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

Further reading

edit- Matto Mildenberger & Leah C. Stokes (2021). "The Energy Politics of North America". The Oxford Handbook of Energy Politics.

- Oil and Natural Gas Industry Tax Issues in the FY2014 Budget Proposal Congressional Research Service

External links

edit- US Department of Energy

- Energy Information Administration

- USDA energy

- United States Energy Association (USEA)

- US energy stats

- ISEA – Database of U.S. International Energy Agreements

- Retail sales of electricity and associated revenue by end-use sectors through June 2007 (Energy Information Administration)

- International Energy Agency 2007 Review of US Energy Policies