Svan (ლუშნუ ნინ lušnu nin; Georgian: სვანური ენა, romanized: svanuri ena) is a Kartvelian language spoken in the western Georgian region of Svaneti primarily by the Svan people.[2][3] With its speakers variously estimated to be between 30,000 and 80,000, the UNESCO designates Svan as a "definitely endangered language".[4] It is of particular interest because it has retained many features that have been lost in the other Kartvelian languages.

| Svan | |

|---|---|

| ლუშნუ ნინ Lušnu nin | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɫuʃnu nin] |

| Native to | Georgia |

| Region | Svaneti Abkhazia |

| Ethnicity | Svans |

Native speakers | 14,000 (2015)[1] |

Kartvelian

| |

| Georgian script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | sva |

| Glottolog | svan1243 |

| ELP | Svan |

| |

Svan is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Features edit

Familial features edit

Like all languages of the Caucasian language family, Svan has a large number of consonants. It has agreement between subject and object, and a split-ergative morphosyntactic system. Verbs are marked for aspect, evidentiality and "version".

Distinguishing features edit

Svan retains the voiceless aspirated uvular plosive, /qʰ/, and the glides /w/ and /j/. It has a larger vowel inventory than Georgian; the Upper Bal dialect of Svan has the most vowels of any South-Caucasian language, having both long and short versions of /a ɛ i ɔ u æ ø y/ plus /ə eː/, a total of 18 vowels (Georgian, by contrast, has just five).

Its morphology is less regular than that of the other three sister languages, and there are notable differences in conjugation.

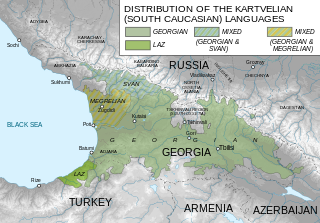

Distribution edit

Svan is the native language of fewer than 30,000 Svans (15,000 of whom are Upper Svan dialect speakers and 12,000 are Lower Svan), living in the mountains of Svaneti, i.e. in the districts of Mestia and Lentekhi of Georgia, along the Enguri, Tskhenistsqali and Kodori rivers. Some Svan speakers live in the Kodori Valley of the de facto independent republic of Abkhazia. Although conditions there make it difficult to reliably establish their numbers, there are only an estimated 2,500 Svan individuals living there.[5]

The language is used in familiar and casual social communication. It has no written standard or official status.[6] Most speakers also speak Georgian. The language is considered endangered, as proficiency in it among young people is limited.

History edit

Svan is the most differentiated member of the four South-Caucasian languages and is believed to have split off in the 2nd millennium BC or earlier, about one thousand years before Georgian and Zan split from each other.

Soviet ethnologist Evdokia Kozhevnikova extensively documented the Svan language during her fieldwork in Svaneti in the 1920s and 1930s.[7]

Dialects edit

The Svan language is divided into the following dialects and subdialects:

Phonology edit

Consonants edit

The consonant inventory of Svan is more or less the same as that of Old Georgian. That is, compared to Modern Georgian, it also has /j/, /q/ and /w/, but the labiodental fricative only appears as an allophone of /w/ in the Ln dialect. Furthermore, the uvular consonants /q/ and /q’/ are realized as affricates, i.e. [q͡χ] and [q͡χʼ].[8]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ მ | n /n/ ნ | |||||

| Plosive | voiced | b /b/ ბ | d /d/ დ | g /ɡ/ გ | |||

| aspirated | p /pʰ/ ფ | t /tʰ/ თ | k /kʰ/ ქ | q /qʰ/ ჴ | |||

| ejective | ṗ /pʼ/ პ | ṭ /tʼ/ ტ | ḳ /kʼ/ კ | q̇ /qʼ/ ყ | ʔ /ʔ/ ჸ | ||

| Affricate | voiced | ʒ /d͡z/ ძ | ǯ /d͡ʒ/ ჯ | ||||

| aspirated | c /t͡sʰ/ ც | č /t͡ʃʰ/ ჩ | |||||

| ejective | ċ /t͡sʼ/ წ | čʼ /t͡ʃʼ/ ჭ | |||||

| Fricative | voiced | (v [v] ვ) | z /z/ ზ | ž /ʒ/ ჟ | ɣ /ʁ/ ღ | ||

| voiceless | s /s/ ს | š /ʃ/ შ | x /χ/ ხ | h /h/ ჰ | |||

| Approximant | w /w/უ̂ | l /l/ ლ | y /j/ ჲ | ||||

| Trill | r /r/ რ | ||||||

Vowels edit

The vowel inventory of Svan varies between different dialects. For instance, Proto-Svan phonemic long vowels occur in the Upper Bal, Cholur and Lashkh dialects, but have been lost in the Lentekh and Lower Bal dialects. Compared to Georgian, Svan also have a central or back unrounded high vowel /ə/ (realized as [ɯ]~[ɨ]), the low front /æ/ (except for Lashkh) and the front rounded vowels /œ/ and /y/ (also except for Lashkh). The front rounded vowels are often realized as diphthongs [we] and [wi] and are therefore sometimes not treated as separate phonemes.[8]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | /i/ ი i |

/iː/ ი̄ ī |

/y/ უ̈, ჳი ü |

/yː/ უ̄̈ ṻ |

/u/ უ u |

/uː/ უ̄ ū | ||

| Close-mid | /e/ e |

/eː/ ჱ ē |

/ə/[a] ჷ ə |

/əː/ ჷ̄ ə̄ |

||||

| Open-mid | /œ/ ო̈, ჳე ö |

/œː/ ო̄̈ ō̈ |

/ɔ/ ო o |

/ɔː/ ო̄ ō | ||||

| Open | /æ/ ა̈ ä |

/æː/ ა̄̈ ā̈ |

/ɑ/ ა a |

/ɑː/ ა̄ ā | ||||

- ^ Realized as [ɯ] or [ɨ].

Alphabet edit

The alphabet, illustrated above, is similar to the Mingrelian alphabet, with a few additional letters otherwise obsolete in the Georgian script:[9]

- ჶ [f]

- ჴ /q⁽ʰ⁾/

- ჸ /ʔ/

- ჲ /j/

- უ̂ /w/

- ჷ /ə/

- ჱ /eː/

These are supplemented by diacritics on the vowels (the umlaut for front vowels and macron for length), though those are not normally written. The digraphs

- ჳი ("wi") /y/

- ჳე ("we") /œ/

are used in the Lower Bal and Lentekh dialects, and occasionally in Upper Bal; these sounds do not occur in Lashkh dialect.

References edit

Notes edit

- ^ Svan at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Levinson, David. Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook. Phoenix: Oryx Press, 1998. p 34

- ^ Tuite, Kevin (1991–1996). "Svans". In Friedrich, Paul; Diamond, Norma (eds.). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Vol. VI. Boston, Mass.: G.K. Hall. p. 343. ISBN 0-8168-8840-X. OCLC 22492614.

- ^ UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger

- ^ DoBeS (Dokumentation Bedrohter Sprachen, Documentation of Endangered Languages)

- ^ Tuite, Kevin (2017). "Language and emergent literacy in Svaneti". In Korkmaz, Ramazan; Doğan, Gürkan (eds.). Endangered Languages of the Caucasus and Beyond. Montréal: Brill. pp. 226–243. ISBN 978-90-04-32564-7.

- ^ Margiani, Ketevan (2023). "Texts in the Svan Language by Dina Kozhevnikova (Linguistic Analysis)". In Kvantidze, Gulnara; Khizanashvili, Manana (eds.). Dina Kozhevnikova: Ethnographical Records (in Georgian). Tbilisi: Georgian National Museum. p. 82. ISBN 978-9941-9822-1-7.

- ^ a b Tuite, Kevin (2020). "The Svan language". Manuscript.

- ^ "Svan alphabet, language and prounciation". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

General references edit

- Palmaitis, Mykolas Letas; Gudjedjiani, Chato (1986). Upper Svan: Grammar and texts. Vilnius: Mokslas.

- Oniani, Aleksandre (2005). Die swanische Sprache (Teil I: Phonologie, Morphonologie, Morphologie des Nomens; Teil II: Morphologie des Verbs, Verbal-nomen, Udeteroi). Translated by Fähnrich, Heinz. Jena: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität.

- Tuite, Kevin (1997). Svan (PDF). Languages of the World, Materials, vol. 139. Munich: LINCOM-Europa. ISBN 978-3895861543.

External links edit

- Svan at TITUS database

- ECLING - Svan (includes audio/video samples).

- Svan alphabet and language at Omniglot

- Svan Youth literature in Svan language

- Svan DoReCo corpus compiled by Jost Gippert. Audio recordings of narrative texts, with transcriptions time-aligned at the phone level and translations.

- Svan (Lashkh Dialect) recordings and audio samples.