Religion has been a major influence on the societies, cultures, traditions, philosophies, artistic expressions and laws within present-day Europe. The largest religion in Europe is Christianity.[1] However, irreligion and practical secularisation are also prominent in some countries.[2][3] In Southeastern Europe, three countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania) have Muslim majorities, with Christianity being the second-largest religion in those countries. Ancient European religions included veneration for deities such as Zeus. Modern revival movements of these religions include Heathenism, Rodnovery, Romuva, Druidry, Wicca, and others. Smaller religions include Indian religions, Judaism, and some East Asian religions, which are found in their largest groups in Britain, France, and Kalmykia.

Little is known about the prehistoric religion of Neolithic Europe. Bronze and Iron Age religion in Europe as elsewhere was predominantly polytheistic (Ancient Greek religion, Ancient Roman religion, Basque mythology, Finnish paganism, Celtic polytheism, Germanic paganism, etc.).

The Roman Empire officially adopted Christianity in AD 380. During the Early Middle Ages, most of Europe underwent Christianization, a process essentially complete with the Christianization of Scandinavia in the High Middle Ages. The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christendom", and many even consider Christianity as the unifying belief that created a European identity,[4] especially since Christianity in the Middle East was marginalized by the rise of Islam from the 8th century. This confrontation led to the Crusades, which ultimately failed militarily, but were an important step in the emergence of a European identity based on religion. Despite this, traditions of folk religion continued at all times, largely independent from institutional religion or dogmatic theology.

The Great Schism of the 11th century and Reformation of the 16th century tore apart Christendom into hostile factions, and following the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, atheism and agnosticism have spread across Europe. Nineteenth-century Orientalism contributed to a certain popularity of Hinduism and Buddhism, and the 20th century brought increasing syncretism, New Age, and various new religious movements divorcing spirituality from inherited traditions for many Europeans. Recent times have seen increased secularisation and religious pluralism.[5]

Religiosity edit

Some European countries have experienced a decline in church membership and church attendance.[6][7] A relevant example of this trend is Sweden where the Church of Sweden, previously the state-church until 2000, claimed to have 82.9% of the Swedish population as its flock in 2000. Surveys showed this had dropped to 72.9% by 2008[8] and to 56.4% by 2019.[9] Moreover, in the 2005 Eurobarometer survey 23%[10] of the Swedish population said that they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force and in the 2010 Eurobarometer survey 34%[2] said the same.

Gallup survey 2008–2009 edit

This section needs to be updated. (June 2022) |

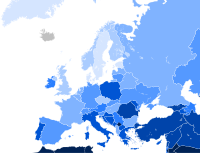

During 2008–2009, a Gallup survey asked in several countries the question "Is religion important in your daily life?" The table and map below shows percentage of people who answered "Yes" to the question.[11][12]

| 0%–9% | |

| 10%–19% (Estonia, Sweden, Denmark) | |

| 20%–29% (Norway, Czech Republic, United Kingdom, Finland) | |

| 30%–39% (France, Netherlands, Belgium, Bulgaria, Russia, Belarus, Luxembourg, Hungary, Albania, Latvia) | |

| 40%–49% (Germany, Switzerland, Lithuania, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Slovenia, Slovakia, Spain) | |

| 50%–59% (Azerbaijan, Serbia, Ireland, Austria) | |

| 60%–69% | |

| 70%–79% (Croatia, Montenegro, Greece, Portugal, Italy, Poland, Cyprus, North Macedonia) | |

| 80%–89% (Turkey, Romania, Malta, Armenia, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina) | |

| 90%–100% (Kosovo, Georgia) | |

| No data |

During 2007–2008, a Gallup poll asked in several countries the question "Does religion occupy an important place in your life?" The table on right shows percentage of people who answered "No".[13]

Eurobarometer survey 2010 edit

The 2010 Eurobarometer survey[2] found that, on average, 51% of the citizens of the EU member states state that they "believe there is a God", 26% "believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" while 20% "don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force". 3% declined to answer. According to a recent study (Dogan, Mattei, Religious Beliefs in Europe: Factors of Accelerated Decline), 47% of French people declared themselves as agnostics in 2003. This situation is often called "Post-Christian Europe". A decrease in religiousness and church attendance in Denmark, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, and Sweden has been noted, despite a concurrent increase in some countries like Greece (2% in 1 year). The Eurobarometer survey must be taken with caution, however, as there are discrepancies between it and national census results. For example, in the United Kingdom, the 2001 census revealed over 70% of the population regarded themselves as "Christian" with only 15% professing to have "no religion", though the wording of the question has been criticized as "leading" by the British Humanist Association.[15] Romania, one of the most religious countries in Europe, witnessed a threefold increase in the number of atheists between 2002 and 2011, as revealed by the most recent national census.[16]

The following is a list of European countries ranked by religiosity, based on the rate of belief, according to the Eurobarometer survey 2010.[2] The 2010 Eurobarometer survey asked whether the person "believes there is a God", "believes there is some sort of spirit or life force", or "doesn't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force".

| Country | "I believe there is a God" |

"I believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" |

"I don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malta | 94% | 4% | 2% |

| Romania | 93% | 6% | 1% |

| Cyprus | 88% | 8% | 3% |

| Poland | 79% | 14% | 5% |

| Greece | 79% | 16% | 4% |

| Italy | 74% | 20% | 6% |

| Ireland | 70% | 20% | 7% |

| Portugal | 70% | 15% | 12% |

| Slovakia | 63% | 23% | 13% |

| Spain | 59% | 20% | 19% |

| Lithuania | 47% | 37% | 12% |

| Luxembourg | 46% | 22% | 24% |

| Hungary | 45% | 34% | 20% |

| Austria | 44% | 38% | 12% |

| Germany | 44% | 25% | 27% |

| Latvia | 38% | 48% | 11% |

| United Kingdom | 37% | 33% | 25% |

| Belgium | 37% | 31% | 27% |

| Bulgaria | 36% | 43% | 15% |

| Finland | 33% | 42% | 22% |

| Slovenia | 32% | 36% | 26% |

| Denmark | 28% | 47% | 24% |

| Netherlands | 28% | 39% | 30% |

| France | 27% | 27% | 40% |

| Estonia | 18% | 50% | 29% |

| Sweden | 18% | 45% | 34% |

| Czech Republic | 16% | 44% | 37% |

| EU27 | 51% | 26% | 20% |

| Turkey (EUCU, not EU) | 94% | 1% | 1% |

| Croatia (joined EU in 2013) | 69% | 22% | 7% |

| Switzerland (EFTA, not EU) | 44% | 39% | 11% |

| Iceland (EFTA, not EU) | 31% | 49% | 18% |

| Norway (EFTA, not EU) | 22% | 44% | 29% |

The decrease in theism is illustrated in the 1981 and 1999 according to the World Values Survey,[17] both for traditionally strongly theist countries (Spain: 86.8%:81.1%; Ireland 94.8%:93.7%) and for traditionally secular countries (Sweden: 51.9%:46.6%; France 61.8%:56.1%; Netherlands 65.3%:58.0%). Some countries nevertheless show increase of theism over the period, Italy 84.1%:87.8%, Denmark 57.8%:62.1%. For a comprehensive study on Europe, see Mattei Dogan's "Religious Beliefs in Europe: Factors of Accelerated Decline" in Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion.

Eurobarometer survey 2019 edit

Self described religion in the European Union (2019)[18]

According to the 2019 Eurobarometer survey about Religiosity in the European Union Christianity is the largest religion in the European Union accounting 64% of the EU population,[18] down from 72% in 2012.[20] Catholics are the largest Christian group in EU, accounting for 41% of EU population, while Eastern Orthodox make up 10%, and Protestants make up 9%, and other Christians account for 4% of the EU population. Non believer/Agnostic account 17%, Atheist 10%, and Muslim 2% of the EU population. 3% refuse to answer or didn't know.[18]

| Country | "Atheist" | "Non believer/Agnostic" | "Atheist + Non believer/Agnostic" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | 2% | 2% | 4% |

| Malta | 2% | 2% | 4% |

| Cyprus | 3% | 4% | 7% |

| Poland | 5% | 4% | 9% |

| Lithuania | 3% | 6% | 9% |

| Greece | 7% | 4% | 11% |

| Slovakia | 6% | 5% | 11% |

| Croatia | 6% | 5% | 11% |

| Portugal | 4% | 8% | 12% |

| Ireland | 7% | 7% | 14% |

| Italy | 5% | 9% | 14% |

| Bulgaria | 8% | 7% | 15% |

| Austria | 4% | 12% | 16% |

| Slovenia | 14% | 4% | 18% |

| Latvia | 6% | 13% | 19% |

| Hungary | 3% | 17% | 20% |

| Denmark | 9% | 13% | 22% |

| Finland | 10% | 14% | 24% |

| Luxembourg | 10% | 16% | 26% |

| Germany | 9% | 21% | 30% |

| Belgium | 10% | 21% | 31% |

| Spain | 12% | 20% | 32% |

| United Kingdom | 19% | 20% | 39% |

| France | 21% | 19% | 40% |

| Estonia | 21% | 27% | 48% |

| Sweden | 16% | 34% | 50% |

| Netherlands | 11% | 41% | 52% |

| Czech Republic | 22% | 34% | 56% |

| EU28 | 10% | 17% | 27% |

Maps edit

Pew Research Poll edit

According to the 2012 Global Religious Landscape survey by the Pew Research Center, 75.2% of the Europe residents are Christians, 18.2% are irreligious, atheist or agnostic, 5.9% are Muslims and 0.2% are Jews, 0.2% are Hindus, 0.2% are Buddhist, and 0.1% adhere to other religions.[21] According to the 2015 Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe survey by the Pew Research Center, 57.9% of the Central and Eastern Europeans identified as Orthodox Christians,[22] and according to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, 71.0% of Western Europeans identified as Christians, 24.0% identified as religiously unaffiliated and 5% identified as adhere to other religions.[23] According to the same study a large majority (83%) of those who were raised as Christians in Western Europe still identify as such, and the remainder mostly self-identify as religiously unaffiliated.[23]

Pew Research Poll edit

| Country | Affiliated Orthodox, Catholic or Muslim (poll 1) |

Unaffiliated (poll 1) |

Other/DK/ref (poll 1)* |

"Believe in God, absolutely certain" (poll 2)** |

"Believe in God, fairly certain" (poll 2)** |

"Believe in God, not too/at all certain" (poll 2)** |

"Do not believe in God" (Poll 2)** |

Atheist (poll 3)*** |

Agnostic (poll 3)*** |

Nothing in particular (poll 3)*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 97 | 2 | 1 | 94 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Georgia | 99 | <1 | 1 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 1 | <1 | ||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 96 | 3 | 1 | 90 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Moldova | 95 | 2 | 3 | 89 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Romania | 91 | 1 | 8 | 64 | 28 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Serbia | 94 | 4 | 1 | 73 | 16 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Croatia | 90 | 7 | 3 | 72 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Greece | 92 | 4 | 4 | 69 | 16 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 1 | |

| Poland | 88 | 7 | 5 | 45 | 35 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Lithuania | 78 | 6 | 17 | 34 | 34 | 7 | 11 | 2 | 4 | |

| Ukraine | 88 | 7 | 5 | 32 | 45 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 4 | |

| Bulgaria | 91 | 5 | 4 | 30 | 40 | 7 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Latvia | 54 | 21 | 25 | 28 | 34 | 7 | 15 | 3 | 18 | |

| Belarus | 86 | 3 | 11 | 26 | 47 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 1 | |

| Hungary | 57 | 21 | 22 | 26 | 26 | 7 | 30 | 5 | 16 | |

| Russia | 81 | 15 | 4 | 25 | 38 | 10 | 15 | 4 | 1 | 10 |

| Czech Republic | 22 | 72 | 6 | 13 | 13 | 3 | 66 | 25 | 1 | 46 |

| Estonia | 26 | 45 | 29 | 13 | 24 | 7 | 45 | 9 | 1 | 35 |

(*) 13% of respondents in Hungary identify as Presbyterian. In Estonia and Latvia, 20%

and 19%, respectively, identify as Lutherans. And in Lithuania, 14% say they are "just a

Christian" and do not specify a particular denomination. They are included in the "other"

category.

(**) Identified as "don't know/refused" from the "other/idk/ref" column are excluded from this statistic.

(***) Figures may not add to subtotals due to rounding.

| Country | A holy book (e.g. Bible) is written by men, not the word of God |

A holy book is the word of God |

|---|---|---|

| Georgia | 9% |

88% |

| Armenia | 9% |

87% |

| Moldova | 10% |

87% |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 14% |

81% |

| Romania | 18% |

76% |

| Ukraine | 21% |

63% |

| Poland | 24% |

61% |

| Serbia | 28% |

59% |

| Greece | 28% |

58% |

| Croatia | 29% |

58% |

| Russia | 30% |

58% |

| Belarus | 27% |

57% |

| Bulgaria | 41% |

43% |

| Lithuania | 43% |

42% |

| Hungary | 41% |

41% |

| Latvia | 38% |

40% |

| Estonia | 58% |

26% |

| Czech Republic | 65% |

21% |

(**) Identified with answers "don't know/refused" are not shown.

Abrahamic religions edit

Bahá'í Faith edit

The first newspaper reference to the religious movement began with coverage of the Báb, whom Bahá'ís consider the forerunner of the Bahá'í Faith, which occurred in The Times on 1 November 1845, only a little over a year after the Báb first started his mission.[25] British, Russian, and other diplomats, businessmen, scholars, and world travelers also took note of the precursor Bábí religion[26] most notably in 1865 by Frenchman Arthur de Gobineau who wrote the first and most influential account. In April 1890 Edward G. Browne of Cambridge University met Bahá'u'lláh, the prophet-founder of the Bahá'í Faith, and left the only detailed description by a Westerner.[27]

Starting in the 1890s Europeans began to convert to the religion. In 1910 Bahá'u'lláh's son and appointed successor, 'Abdu'l-Bahá embarked on a three-year journey to including Europe and North America[28] and then wrote a series of letters that were compiled together in the book titled Tablets of the Divine Plan which included mention of the need to spread the religion in Europe following the war.[29]

A 1925 list of "leading local Bahá'í Centres" of Europe listed organized communities of many countries – the largest being in Germany.[30] However the religion was soon banned in a couple of countries: in 1937 Heinrich Himmler disbanded the Bahá'í Faith's institutions in Germany because of its 'international and pacifist tendencies'[31] and in Russia in 1938 "monstrous accusations" against Bahá'ís and a Soviet government policy of oppression of religion resulted in Bahá'í communities in 38 cities across Soviet territories ceasing to exist.[32] However the religion recovered in both countries. The religion has generally spread such that in recent years the Association of Religion Data Archives estimated the Bahá'ís in European countries to number in hundreds to tens of thousands.[33]

Christianity edit

The majority of Europeans describe themselves as Christians, divided into a large number of denominations.[1] Christian denominations are usually classed in three categories: Catholicism (consider only two groups, the Roman-Latin Catholic and the Eastern Greek and Armenian Catholics), Orthodoxy (consider only two groups, the Eastern Byzantine Orthodox and the Armenian Apostolic which is within the Oriental Orthodox Church) and Protestantism (a diverse group including Lutheranism, Calvinism and Anglicanism as well as numerous minor denominations, including Baptists, Methodism, Evangelicalism, Pentecostalism, etc.).

Christianity, more specifically the Catholic Church, which played an important part in the shaping of Western civilization since at least the 4th century.[35][36] Historically, Europe has been the center and "cradle of Christian civilization".[37][38][39][40]

European culture, throughout most of its recent history, has been heavily influenced by Christian belief and has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture.[41] The Christian culture was one of the more dominant forces to influence Western civilization, concerning the course of philosophy, art, music, science, social structure and architecture.[41][42] The civilizing influence of Christianity includes social welfare,[43] founding hospitals,[44] economics (as the Protestant work ethic),[45][46] politics,[47] architecture,[48] literature[49] and family life.[50]

Christianity is still the largest religion in Europe.[51] According to a survey about Religiosity in the European Union in 2019 by Eurobarometer, Christianity was the largest religion in the European Union accounting 64% of EU population,[18] down from 72% in 2012.[20] Catholics were the largest Christian group in EU, and accounted for 41% of the EU population, while Eastern Orthodox made up 10%, Protestants made up 9%, and other Christians 4%.[18] According to a 2010 study by the Pew Research Center, 76.2% of the European population identified themselves as Christians,[52] constitute in absolute terms the world's largest Christian population.[53]

According to Scholars, in 2017, Europe's population was 77.8% Christian (up from 74.9% 1970),[54][55] these changes were largely result of the collapse of Communism and switching to Christianity in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries.[54]

Christian denominations edit

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (August 2017) |

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (December 2017) |

- Catholicism (majorly followed to the Roman–Latin Catholic Church with various minorities of the few Greek Catholic Churches in the Eastern European regions, and the Armenian Catholic Church in Armenia and its diaspora) is the largest denomination with adherents mostly existing in Latin Europe (which includes France,[56] Italy,[56] Spain,[56] Portugal,[56] Malta,[56] San Marino,[56] Monaco,[56] Vatican City,[56]); southern [Wallon] Belgium,[56] Czech Republic, Ireland,[56] Lithuania,[56] Poland,[56] Hungary,[56] Slovakia,[56] Slovenia,[56] Croatia,[56] western Ukraine, parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Mostly in predominantly Croat areas), but also the southern parts of Germanic Europe (which includes Austria, Luxembourg, northern Flemish Belgium, southern and western Germany, parts of the Netherlands, parts of Switzerland, and Liechtenstein).

- Orthodox Christianity (the churches are in full communion, i.e. the national churches are united in theological concept and part of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Eastern Orthodox Church)

- Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

- Russian Orthodox Church

- Serbian Orthodox Church

- Romanian Orthodox Church

- Church of Greece

- Bulgarian Orthodox Church

- Georgian Orthodox Church

- Finnish Orthodox Church

- Cypriot Orthodox Church

- Albanian Orthodox Church

- Polish Orthodox Church

- Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia

- Ukrainian Orthodox Church

- Turkish Orthodox Church

- Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric

- Montenegrin Orthodox Church

- Oriental Orthodoxy

- Protestantism

- Lutheranism

- Independent Evangelical-Lutheran Church

- Danish National Church

- Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

- United Protestant Church of France

- Protestant Church in Germany

- Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Hungary

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia

- Church of Norway

- Church of Sweden

- Anglicanism

- Calvinism

- Lutheranism

- Restorationism

- Other

There are numerous minor Protestant movements, including various Evangelical congregations.

Islam edit

Islam came to parts of European islands and coasts on the Mediterranean Sea during the 8th-century Muslim conquests. In the Iberian Peninsula and parts of southern France, various Muslim states existed before the Reconquista; Islam spread in southern Italy briefly through the Emirate of Sicily and Emirate of Bari. During the Ottoman expansion, Islam was spread from into the Balkans and even part of Central Europe. Muslims have also been historically present in Ukraine (Crimea and vicinity, with the Crimean Tatars), as well as modern-day Russia, beginning with Volga Bulgaria in the 10th century and the conversion of the Golden Horde to Islam. In recent years,[when?] Muslims have migrated to Europe as residents and temporary workers.

According to the Pew Forum, the total number of Muslims in Europe in 2010 was about 44 million (6%).[58] While the total number of Muslims in the European Union in 2007 was about 16 million (3.2%).[59] Data from the 2000s for the rates of growth of Islam in Europe showed that the growing number of Muslims was due primarily to immigration and higher birth rates.[60]

Muslims make up 99% of the population in Turkey,[61] Northern Cyprus,[62][63] 96% in Kosovo,[64] 56% in Albania,[65][66] 51% in Bosnia and Herzegovina,[67] 32.17% in North Macedonia,[68][69] 20% in Montenegro,[70] between 10 and 15% in Russia,[71] 7–9% in France,[72][73][74] 8% in Bulgaria,[75] 6% in the Netherlands, 5% in Denmark, United Kingdom and Germany,[76][77][78] just over 4% in Switzerland and Austria, and between 3 and 4% in Greece.

A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2016 found that Muslims make up 4.9% of all of Europe's population.[79] According to a same study conversion does not add significantly to the growth of the Muslim population in Europe, with roughly 160,000 more people leaving Islam than converting into Islam between 2010 and 2016.[79]

Judaism edit

The Jews were dispersed within the Roman Empire from the 2nd century.[80] At one time Judaism was practiced widely throughout the European continent; throughout the Middle Ages, Jews were accused of ritual murder and faced pogroms and legal discrimination. The Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany decimated the Jewish population, and today, France is home to the largest Jewish community in Europe with 1% of the total population (between 483,000 and 500,000 Jews).[81][82] Other European countries with notable Jewish populations include the United Kingdom (291,000 Jews),[82] Germany (119,000), and Russia (194,000) which is home to Eastern Europe's largest Jewish community.[82] The Jewish population of Europe in 2010 was estimated to be approximately 1.4 million (0.2% of European population) or 10% of the world's Jewish population.[83]

Deism edit

During the Enlightenment, Deism became influential especially in France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Biblical concepts were challenged by concepts such as a heliocentric universe and other scientific challenges to the Bible.[84] Notable early deists include Voltaire, Kant, and Mendeleev.[85]

Irreligion edit

The trend towards secularism during the 20th and 21st centuries has a number of reasons, depending on the individual country:

- France has been traditionally laicist since the French Revolution. Today the country is 25%[86] to 32%[87] irreligious. The remaining population is made up evenly of both Christians and people who believe in a god or some form of spiritual life force, but are not involved in organized religion.[88] French society is still secular overall.

- Some parts of Eastern Europe were secularized as a matter of state doctrine under communist rule in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Albania was an officially (and constitutionally binding) atheist state from 1967 to 1991.[89] The countries where the most people reported no religious belief were France (33%), the Czech Republic (30%), Belgium (27%), Netherlands (27%), Estonia (26%), Germany (25%), Sweden (23%) and Luxembourg (22%).[90] The region of Eastern Germany, which was also under communist rule, is by far the least religious region in Europe.[91][92] Other post-communist countries, however, have seen the opposite effect, with religion being very important in countries such as Romania, Lithuania and Poland.

The trend towards secularism has been less pronounced in the traditionally Catholic countries of Mediterranean Europe. Greece as the only traditionally Eastern Orthodox country in Europe which has not been part of the communist Eastern Bloc also retains a very high religiosity, with in excess of 95% of Greeks adhering to the Greek Orthodox Church.

According to a Pew Research Center Survey in 2012 the religiously unaffiliated (atheists and agnostics) make up about 18.2% of the European population in 2010.[93] According to the same survey the religiously unaffiliated make up the majority of the population in only two European countries: Czech Republic (76%) and Estonia (60%).[3] A newer study (released in 2015) found that in the Netherlands there is also an irreligious majority of 68%.[94]

Atheism and agnosticism edit

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, atheism and agnosticism have increased, with falling church attendance and membership in various European countries.[95] The 2010 Eurobarometer survey found that on total average, of the EU28 population, 51% "believe there is a God", 26% "believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", and 20% "don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force".[2] Across the EU, belief was higher among women, increased with age, those with a strict upbringing, those with the lowest level of formal education and those leaning towards right-wing politics.[90]: 10–11 Results were varied widely between different countries.[2]

According to a survey measuring religious identification in the European Union in 2019 by Eurobarometer, 10% of EU citizens identify themselves as atheists.[18] As of May 2019[update], the top seven European countries with the most people who viewed themselves as atheists were Czech Republic (22%), France (21%), Sweden (16%), Estonia (15%), Slovenia (14%), Spain (12%) and Netherlands (11%).[18] 17% of EU citizens called themselves non-believers or agnostics and this percentage was the highest in Netherlands (41%), Czech Republic (34%), Sweden (34%), United Kingdom (28%), Estonia (23%), Germany (21%) and Spain (20%).[18]

Modern Paganism edit

Germanic edit

Heathenism or Esetroth (Icelandic: Ásatrú), and the organised form Odinism, are names for the modern folk religion of the Germanic nations.

In the United Kingdom Census 2001, 300 people registered as Heathen in England and Wales.[96] However, many Heathens followed the advice of the Pagan Federation (PF) and simply described themselves as "Pagan", while other Heathens did not specify their religious beliefs.[96] In the 2011 census, 1,958 people self-identified as Heathen in England and Wales. A further 251 described themselves as Reconstructionist and may include some people reconstructing Germanic paganism.[97]

Ásatrúarfélagið (Esetroth Fellowship) was recognized as an official religion by the Icelandic government in 1973. For its first 20 years it was led by farmer and poet Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson. By 2003, it had 777 members,[98] and by 2014, it had 2,382 members, corresponding to 0.8% of Iceland's population.[99] In Iceland, Germanic religion has an impact larger than the number of its adherents.[100]

In Sweden, the Swedish Forn Sed Assembly (Forn Sed, or the archaic Forn Siðr, means "Old Custom") was formed in 1994 and is since 2007 recognized as a religious organization by the Swedish government. In Denmark Forn Siðr was formed in 1999, and was officially recognized in 2003[101] The Norwegian Åsatrufellesskapet Bifrost (Esetroth Fellowship Bifrost) was formed in 1996; as of 2011, the fellowship has some 300 members. Foreningen Forn Sed was formed in 1999, and has been recognized by the Norwegian government as a religious organization. In Spain there is the Odinist Community of Spain – Ásatrú.

Roman edit

The Roman polytheism also known as Religio Romana (Roman religion) in Latin or the Roman Way to the Gods (in Italian 'Via romana agli Déi') is alive in small communities and loosely related organizations, mainly in Italy.

Druidry edit

The religious development of Druidry was largely influenced by Iolo Morganwg.[102] Modern practises aim to imitate the practises of the Celtic peoples of the Iron Age.[103]

Official religions edit

A number of countries in Europe have official religions, including Greece (Orthodox),[104] Liechtenstein,[105] Malta,[106] Monaco,[107] the Vatican City (Catholic);[108] Armenia (Apostolic Orthodoxy); Denmark,[109] Iceland[110][111] and the United Kingdom (England alone) (Anglican).[112] In Switzerland, some cantons are officially Catholic, others Reformed Protestant. Some Swiss villages even have their religion as well as the village name written on the signs at their entrances.

Georgia, while technically has no official church per se, has special constitutional agreement with Georgian Orthodox Church, which enjoys de facto privileged status. Much the same applies in Germany with the Evangelical Church and the Roman Catholic Church, and the Jewish community. In Finland, both the Finnish Orthodox Church and the Lutheran Church are official. England, a part of the United Kingdom, has Anglicanism as its official religion. Scotland, another part of the UK, has Presbyterianism as its national church, but it is no longer "official". In Sweden, the national church used to be Lutheranism, but it is no longer "official" since 2000. Azerbaijan, Czech Republic, Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Serbia, Romania, Russia, Spain and Turkey are officially secular.

Indian religions edit

Buddhism edit

Buddhism is thinly spread throughout Europe, and the fastest growing religion in recent years[113][114] with about 3 million adherents.[115][116] In Kalmykia, Tibetan Buddhism is prevalent.[117]

Hinduism edit

Hinduism is mainly practised among Indian immigrants. It has been growing rapidly in recent years, notably in the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands and Italy.[118] In 2010, there were an estimated 1.4 million Hindu adherents in Europe.[119]

Jainism edit

Jainism, small membership rolls, mainly among Indian immigrants in Belgium and the United Kingdom, as well as several converts from western and northern Europe.[120][121]

Sikhism edit

Sikhism has nearly 700,000 adherents in Europe. Most of the community live in United Kingdom (450,000) and Italy (100,000).[122][123] Around 10,000 Sikhs live in Belgium and France.[124] Netherlands and Germany have a Sikh population of 22,000.[125][126] All other countries, such as Greece, have 5,000 or fewer Sikhs.

Other religions edit

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (February 2016) |

Other religions represented in Europe include:

- Animism

- Confucianism

- Eckankar

- Ietsism

- Raëlism

- Beliefs of the Romani people

- Romuva

- Satanism

- Shinto

- Spiritualism

- Taoism

- Thelema

- Unitarian Universalism

- Yazidism

- Zoroastrianism

- Rastafari communities in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and elsewhere.

- Traditional African Religions (including Muti), mainly in the United Kingdom and France, including

- West African Vodun and Haitian Vodou (Voodoo), mainly among West African and black Caribbean immigrants in the UK and France.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b "Europe". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

Most Europeans adhere to one of three broad divisions of Christianity: Roman Catholicism in the west and southwest, Protestantism in the north, and Eastern Orthodoxy in the east and southeast

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Special Eurobarometer, biotechnology, page 204" (PDF). Fieldwork: Jan–Feb 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Religiously Unaffiliated". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). CUA Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780813216836.

- ^ Hans Knippenberg (2005). The Changing Religious Landscape of Europe. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis. pp. 7–9. ISBN 90-5589-248-3.

- ^ Ronan McCrea (17 June 2013). "Ronan McCrea – Is migration making Europe more secular?". Aeon Magazine. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Church attendance faces decline almost everywhere Archived 9 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 3 July 2011

- ^ "Svenska kyrkans medlemsutveckling år 1972–2008" [Swedish church's membership development in the years 1972–2008]. svenskakyrkan.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original (XLS) on 13 August 2010.

- ^ Svenska kyrkan i siffror Svenska kyrkan

- ^ "Special Eurobarometer: Social values, Science and Technology" (PDF). European Commission Public Opinion. June 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2006.

- ^ a b c Crabtree, Steve (31 August 2010). "Religiosity Highest in World's Poorest Nations". Gallup. Retrieved 27 May 2015. (in which numbers have been rounded)

- ^ a b c GALLUP WorldView – data accessed 17 January 2009

- ^ "Gallup in depth: Religion". Gallup.com. 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ 5 non-EU countries were included in the survey: Croatia (EU member since 1 June 2013), Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey.

- ^ "The Census Campaign 2011". British Humanist Association. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Cristina Lica (4 December 2012). "Tot mai mulţi români "sţau lepadat" de Dumnezeu. Harta ateilor din România" [More and more Romanians "have been rejected" by God. Mapping atheists in Romania] (in Romanian). evz.ro. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Religion and morale: Believe in God". World Values Survey. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Discrimination in the European Union", Special Eurobarometer, 493, European Union: European Commission, 2019, retrieved 8 November 2019 The question asked was "Do you consider yourself to be...?" With a card showing: Catholic, Orthodox Christian, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim – Shia, Muslim – Sunni, Other Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, Non believer/Agnostic and Other. Also space was given for Refusal (SPONTANEOUS) and Don't Know. Jewish, Muslim – Shia, Sikh, Buddhist and Hindu did not reach the 1% threshold.

- ^ "Discrimination in the European Union". Special Eurobarometer. 493. European Commission. 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF), Special Eurobarometer, 383, European Union: European Commission, p. 233, 2012, retrieved 14 August 2013

- ^ "The Global Religious Landscape" (PDF). Pewforum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Being Christian in Western Europe", Pew Research Center, 2018, retrieved 29 May 2018

- ^ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (September 1989). "First Public Mentions of the Bahá'í Faith". Bahá'í Information Office (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (1981), The Babi and Baha'i Religions, 1844–1944: Some Contemporary Western Accounts, Oxford, England: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-102-7

- ^ U.K. Bahá'í Heritage Site. "The Bahá'í Faith in the United Kingdom -A Brief History". Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Bausani, Alessandro; MacEoin, Dennis (1989). "Life and Work". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Abbas, 'Abdu'l-Bahá; Mirza Ahmad Sohrab; trans. and comments (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation.

- ^ Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena. "100 Years of the Bahá'í Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review. Vol. 1998, no. 8. pp. 35–44.

- ^ Kolarz, Walter (1962). Religion in the Soviet Union. Armenian Research Center collection. St. Martin's Press. pp. 470–473. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Notes on the Bábí and Bahá'í Religions in Russia and its Territories", by Graham Hassall, Journal of Bahá'í Studies, 5.3 (Sept.-Dec. 1993)

- ^ "Most Baha'i Nations (2010)". QuickLists → Compare Nations → Religions. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Pew Forum, Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050

- ^ Orlandis, A Short History of the Catholic Church (1993), preface.

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. (2 May 2005). How The Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781596986114.

- ^ A. J. Richards, David (2010). Fundamentalism in American Religion and Law: Obama's Challenge to Patriarchy's Threat to Democracy. University of Philadelphia Press. p. 177. ISBN 9781139484138.

..for the Jews in twentieth-century Europe, the cradle of Christian civilization.

- ^ D'Anieri, Paul (2019). Ukraine and Russia: From Civilied Divorce to Uncivil War. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9781108486095.

..for the Jews in twentieth-century Europe, the cradle of Christian civilization.

- ^ L. Allen, John (2005). The Rise of Benedict XVI: The Inside story of How the Pope Was Elected and What it Means for the World. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141954714.

Europe is historically the cradle of Christian culture, it is still the primary center of institutional and pastoral energy in the Catholic Church...

- ^ Rietbergen, Peter (2014). Europe: A Cultural History. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 9781317606307.

Europe is historically the cradle of Christian culture, it is still the primary center of institutional and pastoral energy in the Catholic Church...

- ^ a b Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. Early Middle Ages: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). CUA Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Church and social welfare,

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Care for the sick

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Property, poverty, and the poor,

- ^ Weber, Max (1905). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Church and state

- ^ Sir Banister Fletcher, History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- ^ Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: "Charting the "Rise of the West": Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), pp. 409–445 (416, table 1)

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica The tendency to spiritualize and individualize marriage

- ^ The Global Religious Landscape A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Major Religious Groups as of 2010 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, p.18

- ^ Global Christianity A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population Archived 1 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, p.15

- ^ "The Global Religious Landscape" (PDF). Pewforum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ a b Zurlo, Gina; Skirbekk, Vegard; Grim, Brian (2019). Yearbook of International Religious Demography 2017. BRILL. p. 85. ISBN 9789004346307.

- ^ Ogbonnaya, Joseph (2017). African Perspectives on Culture and World Christianity. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 2–4. ISBN 9781443891592.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Adherents.com". Archived from the original on 19 August 1999. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ W. A. R. Shadid (1995). Religious Freedom and the Position of Islam in Western Europe. Peters Publishers. p. 35. ISBN 90-390-0065-4.

- ^ Pew Forum, The Future of the Global Muslim Population, January 2011, [1] [2] [3], [4], [5]

- ^ "In Europa leben gegenwärtig knapp 53 Millionen Muslime" [Almost 53 million Muslims live in Europe at present] (in German). islam.de. 8 May 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Muslims in Europe: Country guide". BBC News. 23 December 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "TURKEY" (PDF). Library of Congress: Federal Research Division. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ "Life in North Cyprus: General Information on North Cyprus". Cyprus: European University of Lefke. 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in daily life" (PDF). Milliyet News. KONDA Research and Consultancy. 8 September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2010.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009), Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population (PDF), Pew Research Center, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2009, retrieved 8 October 2009

- ^ "Census of population, households and dwellings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2013: Final results" (PDF). Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina. June 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050" Archived 2 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine in: Pew Research Center. Retrieved 3 December 2016

- ^ Republic of Macedonia, in: Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures. Retrieved 3 December 2016

- ^ "Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Crnoj Gori 2011. godine" [Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011] (PDF) (Press release) (in Serbo-Croatian and English). Statistical office, Montenegro. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Minister of the Interior (28 June 2010). "Entre 5 et 6 Millions de Musulmans en France". Le Point (in French).

- ^ Minister of the Interior (France), Article du Figaro, 28 June 2010

- ^ Minister of the Interior (France), Article de Libération

- ^ "Bulgaria: People and Society". The World Factbook. 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Religion in England and Wales 2011". Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Muslims in Europe: Country guide, BBC News, 23 December 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2007

- ^ Number of Muslims in Germany. Retrieved 13 October 2014

- ^ a b Hackett, Conrad (29 November 2017), "5 facts about the Muslim population in Europe", Pew Research Center

- ^ Gruen, Erich S: The Construct of Identity in Hellenistic Judaism: Essays on Early Jewish Literature and History (2016), p. 284. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG

- ^ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ a b c DellaPergola, Sergio; Dashefsky, Arnold; Sheskin, Ira, eds. (2 November 2012). "World Jewish Population, 2012" (PDF). Current Jewish Population Reports. Storrs, Connecticut: North American Jewish Data Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ "Jews". Pew Research Center. 18 December 2012.

- ^ Encyclopedia Of The Enlightenment Ellen Judy Wilson, Peter Hanns Reill – 2004

- ^ The Founders' Facade R. L. Worthy – 2004

- ^ Ifop (2011). "Les Français et la croyance religieuse" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ CSA [in French] (2013). "CSA décrypte… Le catholicisme en France" (PDF) (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ "Eurobarometer 73.1: Biotechnology Report 2010" (PDF). European Commission Public Opinion. October 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2010.

- ^ Gallagher, Amelia (1997). "The Albanian atheist state, 1967–1991".

- ^ a b "Eurobarometer 225: Social values, Science & Technology" (PDF). Eurostat. 2005. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ "WHY EASTERN GERMANY IS THE MOST GODLESS PLACE ON EARTH". Die Welt. 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "East Germany the 'most atheistic' of any region". Dialog International. 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "religiously unaffiliated". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Two-thirds of people in Netherlands have no religious faith". DutchNews.nl. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil (2005). "Atheism: Contemporary Rates and Patterns" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ a b Blain, Jenny (2005). "Heathenry, the Past, and Sacred Sites in Today's Britain". In Strmiska, Michael F. (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-85109-608-4.

- ^ Office for National Statistics, 11 December 2012, 2011 Census, Key Statistics for Local Authorities in England and Wales. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Strmiska, Michael F.; Sigurvinsson, Baldur A. (2005). "Asatru: Nordic Paganism in Iceland and America". In Strmiska, Michael F. Modern Paganism in World Cultures. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 127–179. ISBN 978-1-85109-608-4. p. 168

- ^ "Populations by religious organizations 1998–2013". Reykjavík, Iceland: Statistics Iceland.

- ^ Strmiska, Michael F.; Sigurvinsson, Baldur A. (2005). "Asatru: Nordic Paganism in Iceland and America". In Strmiska, Michael F. Modern Paganism in World Cultures. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 127–179. ISBN 978-1-85109-608-4. p. 174

- ^ "Forn Siðr – Forn Siðr". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Grimoire for the Apprentice Wizard – Page 353, Oberon Zell-Ravenheart – 2004

- ^ Bonewits 2006. pp. 128–140.

- ^ "Σύνταγμα". www.hellenicparliament.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Constitution Religion at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 March 2009) (archived from the original on 26 March 2009).

- ^ "Constitution of Malta, Article 2". legirel.cnrs.fr. 21 September 1964. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Constitution de la Principauté, Article 9" [Constitution of the Principality, Article 9]. Principaute De Monaco, Ministère d'Etat (in French). 17 December 1962. Archived from the original on 16 April 2007.

- ^ "Vatican City". Catholic-Pages.com. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Denmark – Constitution: Section 4 State Church, International Constitutional Law.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Iceland: Article 62, Government of Iceland.

- ^ "Statistics Iceland – Statistics » Population » Religious organisations". Statice.is. 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "The History of the Church of England". The Archbishops' Council of the Church of England. Retrieved 24 May 2006.

- ^ "U.S.Religious Landscape Survey Religious Affiliation: Diverse and Dynamic" (PDF). The Pew Forum. February 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ Buddhism fastest growing religion in West. Asian Tribune (7 April 2008). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Vipassana Foundation – Buddhists around the world". Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "The Buddhist World: Spread of Buddhism to the West". buddhanet.net.

- ^ Contemporary Buddhist Revival in Kalmykia: Survey of the Present State of Religiosity | AsiaPortal – Infocus Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Infocus.asiaportal.info (6 February 2012). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Adherents by Location". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 1999. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Center, Pew Research (2 April 2015). "Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Paul Weller (2005). "Jain Origins and Key Organisations in the UK". multifaithcentre.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- ^ A Brief Introduction to Jainism | religion | resources Archived 9 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Kwintessential.co.uk. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ UK | Wales | South East Wales | Sikhs celebrate harvest festival. BBC News (10 May 2003). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ NRI Sikhs in Italy. Nriinternet.com (15 November 2004). Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ [6][dead link]

- ^ Sikhs in Nederland – Introduction. Sikhs.nl. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Sikhs in Germany Seek Meeting with German Leaders on Turban Issue. Fateh.sikhnet.com (20 May 2004). Retrieved 28 July 2013.