Prostitution in Australia

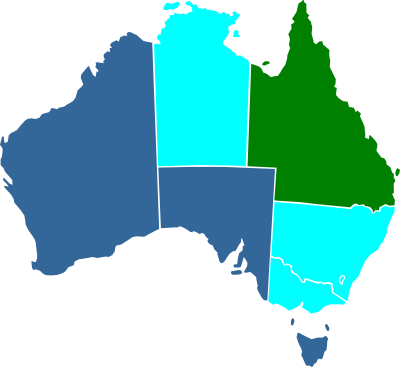

Prostitution in Australia is governed by state and territory laws, which vary considerably, although none ban the selling of sex itself.

- Tasmania, Western Australia and South Australia operate under an abolitionism framework, where the selling of sex itself is not illegal, but activities such as keeping brothels and pimping are illegal.[1][2][3][4]

- The Australian Capital Territory operates under a legalisation framework, where sex work is legal, but brothels must be licensed and can face criminal penalties for operating without a license. Private sex work is legal if the sex worker is working alone.[1][5]

- The Northern Territory, New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria operate under a decriminalisation framework, where most criminal penalties associated with sex work have been removed and brothels or prostitutes are not required to be licensed, however all jurisdictions still have some remaining regulations in regards to where prostitutes or brothels can operate, or on other activities such as advertising.[1][6][7][8][9]

There is no evidence of pre-colonial prostitution amongst Indigenous Australians, however sexual practices more consistent with the modern understanding of polygamy were common, such as the exchange of women to demonstrate friendship. Colonial-era prostitution was controlled via legislation such as the colonial versions of the Contagious Diseases Acts, passed in Victoria and Queensland. Although colonies such as South Australia chose not to pass any CD Act, seeing it as "infringement on the rights of women and official condoning of immorality".[10] After Federation, criminal law was left in the hands of the states, which by and large did not make selling of sex itself illegal, although many acts associated with it such as solicitation, brothel keeping, and leasing accommodations were made illegal.[11]

From the 1970s onwards, prostitution restrictions have generally eased. A 1990 Australian Institute of Criminology report recommended decriminalization of prostitution.[12] New South Wales decriminalized street-based sex work in 1979, using a model subsequently adopted by jurisdictions such as New Zealand, and made brothels legal in 1995.[13]

The United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), which issues regular statistics on sex work, estimated there were around 20,500 sex workers in Australia in 2016.[14] Scarlet Alliance, a national peer sex worker NGO, provides advocacy for sex workers in Australia.

Queensland since 2 August 2024[15] is the most recent state to decriminalise sex work, removing most criminal penalties associated with sex work and abolishing the brothel licensing systems.[16][17][18] Victoria decriminalised sex work in 2023.[19] The Northern Territory decriminalised sex work in 2019.[20]

History

editSex work in Australia has operated differently depending on the period of time evaluated. For this reason discussion is divided into three distinct periods: convict, late colonial, and post-federation. Pre-colonial "prostitution" among Aboriginal peoples is not considered here, since it bore little resemblance to contemporary understanding of the term.[10] The arrival of the Europeans changed this "wife exchange" system, once they started exchanging their European goods for sexual services from Aboriginal women.[10] During the convict period, English common law applied, and dealt with brothel keeping, disorderly houses, and public nuisance. The late colonial period viewed prostitution as a public health issue, through the Contagious Diseases Acts, versions of which passed in Victoria and Queensland, with compulsory examination of prostitutes and detention in "lock hospitals" if found to be carrying a "venereal disease". South Australia chose not to pass any CD Act, seeing it as "infringement on the rights of women and official condoning of immorality". Since Federation in 1901, the emphasis has been on criminalising activities associated with prostitution. Although not explicitly prohibiting paid sex, the criminal law effectively produced a de facto prohibition.[21]

Convict period 1788–1840

editProstitution probably first appeared in Australia at the time of the First Fleet in 1788. Some of the women transported to Australia had previously worked in prostitution, while others chose the profession due to economic circumstances, and a severe imbalance of the sexes. While the 1822 Bigge Inquiry refers to brothels, these were mainly women working from their own homes.[21]

Colonial period 1840–1901

editIn the colonial period, prior to federation, Australia adopted the Contagious Diseases Acts of the United Kingdom between 1868 and 1879 in an attempt to control venereal disease in the military, requiring compulsory inspection of women suspected of prostitution, and could include incarceration in a lock hospital.[22]

Japan exported prostitutes called Karayuki-san during the Meiji and Taisho periods to China, Canada, the United States, Australia, French Indochina, British Malaya, British Borneo, British India and British East Africa where they served western soldiers and Chinese coolies.[23] Japanese prostitutes were also in other European colonies in Southeast Asia like Singapore as well as Australia and the US.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][relevant?]

Federal period 1901–1970s

editAfter federation, criminal law was left in the hands of the states. But criminal law relating to prostitution only dates from around 1910. These laws did not make the act of prostitution illegal but did criminalise many activities related to prostitution. These laws were based on English laws passed between 1860 and 1885, and related to soliciting, age restrictions, brothel keeping, and leasing accommodation.[11]

Post 1970s

editSince the 1970s there has been a change toward liberalisation of prostitution laws, but although attitudes to prostitution are largely homogenous, the actual approaches have varied. A May 1990 Australian Institute of Criminology report recommended that prostitution not be a criminal offence, since the laws were ineffective and endangered sex workers.[12] The NSW Wood Royal Commission into Police Corruption in 1995 recommended sex work be decriminalised to curb corruption and abuse of power..[31]

Following South Korea passing its Anti-prostitution Law and subsequent crackdowns on brothels and prostitution, many Korean sex workers moved abroad, including to Australia. In 2011 Korea's Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated there to be 1,000 Korean sex workers in Australia.[32] A 2022 investigation by the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission and other agencies alleged that 14 Australian-based overseas student education providers worked with crime syndicates to obtain student visa for Korean sex workers.[33]

The United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS UNAIDS has estimated the number of sex workers in Australia in 2012–2014 as between 20,000 and 25,000.[14] Scarlet Alliance, a national peer sex worker NGO, provides advocacy for sex workers in Australia.[34]

Health

editDespite discriminatory STI, BBV and HIV laws targeted at sex workers, peer education has been effective at keeping STIs in the sex worker population at a low level, similar to the general population, and comparable among the states.[35] Although there had been claims that sex workers were responsible for STI levels in mining communities, subsequent research has shown this not to be true.[36]

Human trafficking in Australia

editThe number of people trafficked into or within Australia is unknown. Estimates given to a 2004 parliamentary inquiry into sexual servitude in Australia ranged from 300 to 1,000 trafficked women annually.[37]

In 2006, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Trafficking in persons: global patterns lists Australia as one of 21 trafficking destination countries in the high category.

Australia did not become a party to the Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others when it was implemented in 1949. It has implemented in 1999[38] the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime,[39] to which it is a party. Australia has also ratified on 8 January 2007 the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography, which requires it to prohibit, besides other things, child prostitution. For the purpose of the Protocol, a child is any human being under the age of 18, unless an earlier age of majority is recognised by a country's law. In all Australian jurisdictions, the minimum age at which a person can engage in prostitution is 18 years, although it is argued against the age of consent, and it is always illegal to engage another in prostitution.

A 2020 research on migration, sex work and trafficking showed that, due to the decriminalisation of sex work in some of its states and to a recent increase in work visa opportunities for sections of migrant sex workers, the numbers of human trafficking victims into the sex industry in Australia had dramatically decreased.

Australian Capital Territory

editSex work in the Australian Capital Territory is governed by the Sex Work Act 1992,[40] following partial decriminalisation in 1992; that Act was originally known as the Prostitution Act 1992, being changed to its current name by the Prostitution Act (Amendment) Act 2018. Brothels are legal, but sex workers were required to register with the Office of Regulatory Services (ORS), subsequently Access Canberra.[41] The ORS also registered and regulated brothels and escort agencies. Sex workers may work privately but must work alone. Soliciting remains illegal (Section 19).

Subsequent amending acts include the Prostitution Amendment Act 2002[42] and the Justice and Community Safety Legislation Amendment Act 2011[43](Part 1.7), a minor administrative amendment.

History

editPrior to passage of the Prostitution Act 1992, prostitution policy in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) consisted of "containment and control" under the Police Offences Act 1930[44]This prohibited keeping a brothel, persistently soliciting in a public place, or living on the earnings of prostitution. This law was not enforced. In 1991 a report entitled Prostitution in the ACT: Interim Report (Australian Capital Territory) was produced by the Select Committee on HIV, Illegal Drugs and Prostitution describing the then state of the industry, the shortcomings of the law, and the possible reforms available. Having considered the example of other Australian States that had adopted various other models, the committee recommended decriminalisation, which occurred in the 1992 Prostitution Act.[45] Sex workers and brothel owners were required to register with the Office of Regulatory Services (ORS), subsequently Access Canberra, as were escort agencies, including sole operators.[41]

Legislative review 2011

editThe legal situation was reviewed again with a Standing Committee on Justice and Community Safety's inquiry into the ACT Prostitution Act 1992, following the death of a 16-year-old woman, Janine Cameron, from a heroin overdose in a brothel in 2008.[46]

The inquiry was established on 28 October 2010. The committee, chaired by ACT Liberal MLA Vicki Dunne, devised terms of reference that were as follows:

- the form and operation of the Act

- identifying regulatory options, including the desirability of requiring commercially operated brothels to maintain records of workers and relevant proof of age, to ensure that all sex workers are over the age of 18 years

- the adequacy of, and compliance with, occupational health and safety requirements for sex workers

- any links with criminal activity

- the extent to which unlicensed operators exist within the ACT

- other relevant matter[47]

Written submissions were required by 26 February 2011 at which time 58 submissions had been received.[48]Submissions to the committee included Scarlet Alliance.[49] The Alliance requested changes that would allow sex workers to work together, the removal of registration (which is rarely complied with),[50] and the repeal of sections 24 and 25 dealing with sexually transmitted diseases. The Eros Association, which represents the industry also called for removal of registration and for an expansion into residential areas.[50] As in other States and Territories, conservative Christian groups such as the Australian Christian Lobby (ACL) called for criminalising clients. [51] Groups supporting this position included the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women Australia,[52][53] and the Catholic Church.[54] Sex workers argued against it.[55] Ms Dunne stated that the committee would consider exit schemes;[56] however Attorney-General Simon Corbell stated that it was unlikely there will be any substantive changes to the status quo.[57] The committee completed its hearings on evidence on 13 July 2011,[58] and issued its report in February 2012.[59] The Government issued a formal response in June,[60][61][62] stating it would follow most of the recommendations and that the inquiry had affirmed that sex work was a legitimate occupation.

In the October 2012 elections the opposition Liberals campaigned on a platform to oppose allowing more than one sex worker to use a premise in suburban areas[63] but were not successful in preventing a further term of the ALP Green alliance.

Advocacy

editAdvocacy for sex workers in the ACT is undertaken by SWOP ACT (Sex Work Outreach Project).[64]

New South Wales

editNew South Wales (NSW) has almost complete decriminalisation, and has been a model for other jurisdictions such as New Zealand. Brothels are legal in NSW under the Summary Offences Act 1988.[65] The main activities that are illegal are:

- living on the earnings of a prostitute, although persons who own or manage a brothel are exempt

- causing or inducing prostitution (procuring: Crimes Act s.91A, B)

- using premises, or allowing premises to be used, for prostitution that are held out as being available for massage, sauna baths, steam baths, facilities for exercise, or photographic studios

- advertising that a premise is used for prostitution, or advertising for prostitutes

- soliciting for prostitution near or within view of a dwelling, school, church or hospital

- engaging in child prostitution (Crimes Act s.91C–F)[66]

According to a 2009 report in the Daily Telegraph, illegal brothels in Sydney outnumbered licensed operations by four to one.[67]

History

editEarly era

editNSW was founded in 1788 and was responsible for Tasmania until 1825, Victoria until 1851 and Queensland until 1859. It inherited much of the problems of port cities, penal colonies, and the gender imbalance of colonial life. Initially there was little specific legislation aimed at prostitution, but prostitutes could be charged under vagrancy provisions if their behaviour drew undue attention. In 1822 Commissioner Bigge reported stated there were 20 brothels in Sydney, and many women at the Parramatta Female Factory were involved in prostitution.[68] The Prevention of Vagrancy Act 1835 was designed to deal with 'undesirables'.[21] In 1848 the Sydney Female Refuge Society was set up in Pitt Street to care for prostitutes; its buildings were demolished in 1901 to make way for the new Central Railway Station.[69]

The 1859 Select Committee into the Condition of the Working Classes of the Metropolis described widespread prostitution. Nineteenth-century legislation included the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1883 and Police Offences Act 1901. Attempts to pass contagious diseases legislation were resisted, and unlike other States, legislative control was minimal till the general attack on 'vice' of the first decade of the twentieth century which resulted in the Police Offences Amendment Act 1908, and the Prisoners Detention Act. Street prostitution was controlled by the Vagrancy Act 1902 (sec. 4[1] [c]) enabling a woman to be arrested as a 'common prostitute'.[21] This was strengthened by an amendment of the Police Offences (Amendment) Act 1908, which also prohibited living on the earnings.

Modern era

editStrengthening the laws

editThe Vagrancy Act was further strengthened in 1968, making it an offence to 'loiter for the purpose of prostitution' (sec. 4 [1] [k]). These provisions were then incorporated into the Summary Offences Act 1970, s.28.

Decriminalisation

editIn the 1970s an active debate about the need for liberalisation appeared, spearheaded by feminists and libertarians, culminating under the Wran ALP government in the Prostitution Act 1979. Eventually NSW became a model for debates on liberalising prostitution laws. But almost immediately, community pressure started to build for additional safeguards, particularly in Darlinghurst,[21] although police still utilised other legislation such as the Offences in Public Places Act 1979 for unruly behaviour. Eventually, this led to a subsequent partial recriminalisation of street work with the Prostitution (Amendment) Act 1983, of which s.8A stipulates that;

(1) A person in a public street shall not, near a dwelling, school, church or hospital, solicit another person for the purpose of prostitution ...

(2) A person shall not, in a school, church or hospital, solicit another person for the purpose of prostitution.

This resulted in Darlinghurst street workers relocating.[21]

Further decriminalisation of premises followed with the[70] implementation of recommendations from the Select Committee of the Legislative Assembly Upon Prostitution (1983–86). Although the committee had recommended relaxing the soliciting laws, the new Greiner Liberal government tightened these provisions further in 1988 through the Summary Offences Act in response to community pressure.

The current regulatory framework is based on the Crimes Act 1900,[71] Disorderly Houses Act 1943 (renamed Restricted Premises Act in 2002), Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, and Summary Offences Act 1988. The suburbs of King's Cross in Sydney and Islington in Newcastle have been traditional centres of prostitution. New South Wales legalises street prostitution, but community groups in those locations have occasionally lobbied for re-criminalisation.[72]

As promised in its 2011 election campaign, the Liberal Party sought review of the regulation of brothels. In September 2012, it issues a discussion paper on review of the regulations.[73] It stated that the purpose was three-fold, the protection of residential amenity; protection of sex workers and safeguarding public health.[35] Nevertheless, there is no evidence of a negative effect of brothels on the community.[74]

Politics

editGenerally prostitution policy in NSW has been bipartisan. But in 2010 the Liberal (centre-right) opposition announced that it would make prostitution reform part of its campaign for the March 2011 State election. The plan would involve a new licensing authority, following revelations that the sex industry had been expanding and operating illegally as well as in legal premises. The Liberals claimed that organised crime and coercion were part of the NSW brothel scene.[75] The last reform was in 2007, with the Brothels Legislation Act.[76] The Liberals were duly elected as the new government in that election.[77]

Advocacy for sex workers in NSW is undertaken by SWOP NSW (Sex Workers Outreach Project).[78]

Northern Territory

editSex work including the operation of brothels and street work became legal, subject to regulation, in the Northern Territory in 2019 with the passage of the Sex Industry Act[79] which repealed earlier legislation.[80]

History

editUnlike other parts of Australia, the Northern Territory remained largely Aboriginal for much longer, and Europeans were predominantly male. Inevitably this brought European males into close proximity with Aboriginal women. There has been much debate as to whether the hiring of Aboriginal women (Black Velvet) as domestic labour but also as sexual partners constituted prostitution or not.[81] Certainly these inter-racial liaisons attracted much criticism. Once the Commonwealth took over the territory from South Australia in 1911, it saw its role as protecting the indigenous population, and there was considerable debate about employment standards and the practice of 'consorting'.[82]

Pressure from reform came from women's groups such as Women Against Discrimination and Exploitation (WADE). (Bonney 1997) In 1992 the Prostitution Regulation Act reformed and consolidated the common law and statute law relating to prostitution.[83] The first report of the Escort Agency Licensing Board in 1993 recommended further reform, but the Government did not accept this, feeling there would be widespread opposition to legalising brothels. The Attorney-General's Department conducted a review in 1996. A further review was subsequently conducted in 1998.[84] In 2004 The Suppression of Brothels Act 1907 (SA) in its application to the Territory was repealed by the Prostitution Regulation Act 2004 (NT). Under this legislation brothels and street work were illegal, but The Northern Territory Licensing Commission[85] could license Northern Territory residents for a licence to operate an escort agency business.[86] Sole operators were legal and unregulated. Sex workers protested against the fact that the NT was the only part of Australia where workers had to register with the police.[87]

Sex Industry Act 2019

editIn June 2010, the NT Government rejected calls from the NT Sex Workers Outreach Programme for legalisation of brothels. As elsewhere in Australia, legalisation was opposed by the Australian Christian Lobby.[88][89]

The ALP government, elected in 2016, issued a discussion paper in March 2019.[90] Following the consultation period in May, legislation was prepared, and introduced in September as the Sex Industry Bill. It was referred to committee on 18 September, inviting public submissions. The Economic Policy Scrutiny Committee reported on 20 November, with the Government response on the 26th.[91] The Bill was considered and passed by the Legislative Assembly that day, effectively decriminalising prostitution in the Territory, and coming into force on 16 December 2019.[80] The move was welcomed by the United Nations HIV/AIDS Programme (UNAIDS).[92]

Anti-Discrimination Amendment 2022

editIn November 2022, the NT Government passed the Anti-Discrimination Amendment Bill giving full protection of sex workers making it the first region in the world to do so.[93][94]

Queensland

editSince full implementation on 2 August 2024 under proclamation sex work within Queensland has been formally decriminalised and brothels are allowed and permitted. There is still official restrictions on sex work that are “near or close proximity to schools, hospitals and churches” within legislation.[95][96]

History

editMuch emphasis was placed in colonial Queensland on the role of immigration and the indigenous population in introducing and sustaining prostitution, while organisations such as the Social Purity Society described what they interpreted as widespread female depravity. Concerns led to the Act for the Suppression of Contagious Diseases 1868 (31 Vict. No. 40), part of a widespread legislative attempt to control prostitution throughout the British Empire through incarceration in lock hospitals. Brothels were defined in section 231 of the Queensland Criminal Code in 1897, which explicitly defined 'bawdy houses' in 1901. A further act relating to venereal disease control was the Health Act Amendment Act 1911 (2 Geo. V. No. 26). Solicitation was an offence under Clause 132E, and could lead to a fine or imprisonment. Other measures included the long-standing vagrancy laws and local by-laws.

The Fitzgerald Report (Commission of Inquiry into "Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct") of 1989 led to widespread concern regarding the operation of the laws, and consequently a more specific inquiry (Criminal Justice Commission. Regulating morality? An inquiry into prostitution in Queensland) in 1991. This in turn resulted in two pieces of legislation, the Prostitution Laws Amendment Act 1992 and the Prostitution Act 1999.[97]

The Crime and Misconduct Commission reported on the regulation of prostitution in 2004,[98] and on outcall work in 2006.[99][100] Five amendments were introduced between 1999 and 2010. In August 2009 the Prostitution and Other Acts Amendment Bill 2009 was introduced[101][102][103] and assented to in September, becoming the Prostitution and Other Acts Amendment Act 2010[104] proclaimed in March 2011.

South Australia

editBrothels are illegal in South Australia, under the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935[105] and the Summary Offences Act 1953.[106] Soliciting in public places (maximum penalty of $750), receiving money from the prostitution of another, and procuring are illegal ($2,500 or jail for six months), but the act of prostitution itself is not.[107]

History

editEarly era

editDespite the intentions of the founders, prostitution became identified early in the history of the colony, known as the 'social evil', and various government reports during the nineteenth century refer to estimates of the number of people working in prostitution. In 1842, within six years of the founding of the colony, it was reported that there were now "large numbers of females who are living by a life of prostitution in the city of Adelaide, out of all proportion to the respectable population".[21][108]

The Police Act 1844[109] set penalties for prostitutes found in public houses or public places[110] This was consistent with the vagrancy laws then operating throughout the British Empire and remained the effective legislation for most of the remainder of the century, although it had little effect despite harsher penalties enacted in 1863 and 1869. [111]

Following the scandal described by WT Stead in the UK, there was much discussion of the white slave trade in Adelaide, and with the formation of the Social Purity Society of South Australia in 1882 along similar lines to that in other countries, similar legislation to the UK Criminal Law Consolidation Amendment Act 1885 was enacted, making it an offence to procure the defilement of a female by fraud or threat (the 1885 Protection of Young Persons Act).[112] Opinions were divided as to whether to address the issue of prostitution by social reform and 'prevention', or by legislation, and many debates were held concerning the need for licensing and regulation.[111]

The twentieth century saw the Suppression of Brothels Bill 1907, the Venereal Diseases Act of 1920, the Police Act 1936 and Police Offences Act 1953.[111]

Modern era

editWhile current legislation is based on acts of parliament from the 1930s and 1950s, at least six unsuccessful attempts have been made to reform the laws, starting in 1980.[113] In 1978 one of many inquires was launched. Parliament voted a select committee of inquiry in August,[113] renewed following the 1979 election.[113] The Evidence Act 1978 was amended to allow witness immunity.[113]

Millhouse (1980)

editThe committee report (1980) recommended decriminalisation.[113] Robin Millhouse's (former Liberal Attorney-General, but then a new LM and finally Democrat MLA) introduced (27 February 1980) a bill entitled "A Bill for an Act to give effect to the recommendations of the Select Committee of Inquiry into prostitution."[114] It generated considerable opposition in the community and failed on a tied vote in the Assembly on 11 February 1981.[114]

Pickles (1986)

editA further bill was introduced in 1986 (Carolyn Pickles ALP MLC 1985–2002) but dropped on 18 March 1987 due to Liberal opposition and community pressure, with a 13–2 vote.[114]

Gilfillan (1991)

editA number of issues kept sex work in the public eye during 1990 and 1991. The next development occurred on 8 February 1991 when Ian Gilfillan (Australian Democrat MLC 1982–83) stated he would introduce a decriminalisation private members bill. He did so on 10 April 1991[115] but it met opposition from groups such as the Uniting Church and it lapsed when parliament recessed for the winter.[115] Although he introduced a similar bill on 21 August 1991 but on 29 April 1992 a motion passed that resulted in the bill being withdrawn in favour of a reference to the Social Development Committee,[115] although little was achieved by the latter during this time.

Brindal (1993)

editAnother bill came in 1993 and then Mark Brindal, a Liberal backbencher, produced a discussion paper on decriminalisation in November 1994, and on 9 February 1995 he introduced a private member's bill (Prostitution (Decriminalisation) Bill) to decriminalise prostitution and the Prostitution Regulation Bill on 23 February. He had been considered to have a better chance of success than the previous initiatives due to a "sunrise clause" which would set a time frame for a parliamentary debate prior to it coming into effect. He twice attempted to get decriminalisation bills passed, although his party opposed this.[116] The Decriminalisation Bill was discharged on 6 July, and the Regulation Bill was defeated on 17 July.[115]

Cameron (1998)

editMeanwhile, the Committee released its final report on 21 August 1996,[117] but it was not till 25 March 1998 that Terry Cameron MLC (ALP 1995–2006) introduced a bill based on it. It had little support and lapsed when parliament recessed.

Brokenshire (1999)

editThe Liberal Police Minister, Robert Brokenshire, introduced four Bills in 1999, the Prostitution (Licensing) Bill 1999, the Prostitution (Registration) Bill 1999, the Prostitution (Regulation) Bill 1999 and the Summary Offences (Prostitution) Bill 1999, to revise the laws and decriminalise prostitution. The Prostitution (Regulation) Bill was passed by the House of Assembly and received by the Legislative Council on 13 July 2000, but defeated on 17 July 2001, 12:7.[111] The Bill was also supported by the Australian Democrats.[118] The then Minister for the status of Women, Diana Laidlaw is said to have been moved to tears, and called her colleagues "gutless". Another MLC, Sandra Kanck (Australian Democrat 1993–2009) angrily stated that sex workers had been "thrown to the wolves by Parliament".[119]

Key–Gago (2012–2013)

editNo further attempts to reform the law were made for some time, however in 2010 a governing Labor backbencher and former minister, Stephanie Key, announced she would introduce a private members decriminalisation bill.[120][121] Religious groups immediately organised opposition,[122] although the opposition Liberals promised to consider it.[123] Consultations with the blackmarket industry continued[124] and in June 2011 she outlined her intended legislation to amend the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 and the Summary Offences Act 1953 to ensure sex workers had the same industrial rights and responsibilities as other workers, that minors under the age of 18 years were not involved in or associated with sex work, preventing sex services premises from being established within 200 metres of schools, centres for children or places of worship, allowing local government to regulate public amenity, noise, signage and location in relation to sex services premises with more than three workers, promote safe sex education and practice by clients and sex workers, and enable sex workers to report criminal matters to the police like in a similar matter to other citizens, but not where workers could report victims of abuse for intervention assistance or men who sought out such young women as potential rapists or pedophiles.[125]

She presented her proposals to the Caucus in September 2011,[119][126] and tabled a motion on 24 November 2011 "That she have leave to introduce a Bill for an Act to decriminalise prostitution and regulate the sex work industry; to amend the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935, the Equal Opportunity Act 1984, the Fair Work Act 1994, the Summary Offences Act 1953 and the Workers Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1986; and for other purpose".[127]

The proposal was opposed by the Family First Party that had ten per cent of the votes in the Legislative Council, where Robert Brokenshire now opposed decriminalisation.[128] However Police Commissioner, Mal Hyde, stated that the laws need to change.[119] After considerable discussion and some compromises the Sex Work Reform Bill[129][130] was introduced in May 2012, but was defeated by one vote, 20 to 19 in a conscience vote on second reading in November 2012.[131]

Status of Women Minister Gail Gago introduced a similar bill in the Legislative Council, but withdrew it following the defeat of Stephanie Key's Bill.[132] Key introduced another Bill[133] in May 2013.[134][135]

Lensink–Key–Chapman–Franks (2015–2019)

editOn 1 July 2015 Michelle Lensink Liberal MLC introduced an updated version of the Key-Gago legislation as a Private Member's Bill to the South Australian Legislative Council (53rd Parliament),[136] the Statutes Amendment (Decriminalisation of Sex Work) Bill (LC44). Key and Lensink collaborated across party lines to develop the legislation, sexual exploitation being the obvious potential in an industry like this, and its introduction to the Legislative Council was intended to test key elements of the legislation with important opponents in the upper house.[137] The Bill passed the upper house on 6 July 2017 but did not proceed past a second reading on 19 October 2017 in the Assembly, due to prorogation prior to the election the following March, which led to a change of government.[138][139]

The Bill sought to decriminalise sex work by a number of legislative amendments. It would delete the term "common prostitute" from the Criminal Law Consolidation Act (1935) and Summary Offences Act (1953). In addition it would remove common law offences relating to sex work and add "sex work" to the Equal Opportunity Act making discrimination against a person for being a sex worker an offence. Criminal records relating to sex work, including brothels, would be deleted by amending the Spent Convictions Act. The Return to Work Act would be amended to recognise commercial sexual services as in any other business. Sex workers would also be covered under the Work Health and Safety Act[140]

A further attempt to introduce the same Bill (Decriminalisation of Sex Work Bill LC2) was made on 9 May 2018 (54th Parliament), also as a private member's bill sponsored by the Attorney-General Vickie Chapman and Tammy Franks MLC (Greens), and with the support of Liberal Premier Steven Marshall. Statistics published at the time showed that only four people had been fined for offering prostitution services in public between 1 October 2016 and 30 September 2019. In that period, 57 fines for other sex work offences, mainly for managing a brothel or receiving money in a brothel.[141] The bill was again passed in the Legislative Council on 20 June 2019, but this time was defeated in the Assembly 24 to 19 on 13 November 2019 on a conscience vote on second reading.[138] This was the thirteenth bill to fail over a 20-year time period.[107]

Tasmania

editProstitution is legal, but it is illegal for a person to employ or otherwise control or profit from the work of individual sex workers. The Sex Industry Offences Act 2005[142] states that a person must not be a commercial operator of a sexual services business – that is, "someone who is not a self-employed sex worker and who, whether alone or with another person, operates, owns, manages or is in day-to-day control of a sexual services business". Street prostitution is illegal.[143]

This law explicitly outlines that it is illegal to assault a sex worker, to receive commercial sexual services, or provide or receive sexual services unless a prophylactic is used.[144]

History

editProstitution has existed in Tasmania (known as Van Diemen's Land prior to 1856) since its early days as a penal colony, when large numbers of convict women started arriving in the 1820s. Some of the women who were transported there already had criminal records related to prostitution, but most were labelled as such, despite it not being either illegal or grounds for deportation.[145] Prostitution was not so much a profession as a way of life for some women to make ends meet, particularly in a society in which there was a marked imbalance of gender, and convict women had no other means of income.[146] Certainly brothels were established by the end of the 1820s, and records show girls as young as 12 were involved,[146] while prostitution was associated with the female factory at Cascades. Nevertheless, the concept of 'fallen women' and division of women into 'good' and 'bad' was well established. In an attempt to produce some law and order the Vagrancy Act 1824 was introduced.[21][147][148]

The Van Diemen's Land Asylum for the Protection of Destitute and Unfortunate Females (1848) was the first establishment for women so designated. Other attempts were the Penitent's Homes and Magdalen Asylums as rescue missions. In 1879 like other British colonies, Tasmania passed a Contagious Diseases Act (based on similar UK legislation of the 1860s),[146] and established Lock Hospitals in an attempt to prevent venereal diseases amongst the armed forces, at the instigation of the Royal Navy. The Act ceased to operate in 1903 in the face of repeal movements. However, there was little attempt to suppress prostitution itself. What action there was against prostitution was mainly to keep it out of the public eye, using vagrancy laws.[146] Otherwise the police ignored or colluded with prostitution.

Twentieth century

editMore specific legislation dates from the early twentieth century, such as the Criminal Code Act 1924 (Crimes against Morality), and the Police Offences Act 1935.[149] Efforts to reform legislation that was clearly ineffective began in the 1990s. Prior to the 2005 Act, soliciting by a prostitute, living on the earnings of a prostitute, keeping a disorderly house and letting a house to a tenant to use as a disorderly house were criminal offences. Sole workers and escort work, which was the main form of prostitution in the stat, were legal in Tasmania.

Reform was suggested by a government committee in 1999.[150] In December 2002 Cabinet agreed to the drafting of legislation and in September 2003, approved the release of the draft Sex Industry Regulation Bill for consultation. The Bill proposed registration for operators of sexual services businesses.[151]

Consultation with agencies, local government, interested persons and organisations occurred during 2004, resulting in the Sex Industry Regulation Bill 2004 being tabled in Parliament in June 2005.[152] The Bill was supported by sex workers,[153]

The Bill included offence provisions to ensure that Tasmania met its international obligations under the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography (signed by Australia in 2001.) It passed the House of Assembly and was tabled in the Legislative Council, where it was soon clear that it would not be passed, and was subsequently lost. It was replaced by the Sex Industry Offences Act 2005. Essentially, in response to protests the Government moved from a position of liberalising to one of further criminalising. The Act that was passed consolidated and clarified the existing law in relation to sex work by providing that it was legal to be a sex worker and provide sexual services but that it was illegal for a person to employ or otherwise control or profit from the work of individual sex workers. A review clause was included because of the uncertainty as to what the right way to proceed was. The Act commenced 1 January 2006.[154]

2008 review

editIn 2008, the Justice Department conducted a review of the 2005 Act and received a number of submissions, in accordance with the provisions of the Act. [155] The report was tabled in June 2009[156] and expressed concerns about the effectiveness of the legislation, and suggested considering alternatives.

In June 2010, the Attorney-General Lara Giddings announced the Government was going to proceed with reform, using former Attorney-General Judy Jackson's 2003 draft legislation as a starting point.[157] Giddings became the Premier in a minority ALP government in January 2011. However, her Attorney-general, former premier David Bartlett, did not favour this position[158] but resigned shortly afterwards, being succeeded by Brian Wightman.

2012 review

editWightman released a discussion paper in January 2012.[159][160] This was opposed by religious conservative groups, some feminist groups as well as community organisations with concerns about the potential a legalised sex industry to bring organised crime to the state, and included presentations from other States such as Sheila Jeffreys. The government invited submissions on the discussion paper until the end of March, and received responses from a wide range of individuals and groups.[161] Wightman declined to refer the matter to the Law Reform Institute.[162] After the review Wightman stated that there were no plans to make prostitution illegal "Legal issues around the sex industry can be emotive and personal for many people... The Government's top priority is the health and safety of sex workers and the Tasmanian community."[163]

Victoria

editVictoria decriminalised sex work on 1 December 2023, by repealing the Sex Work Act 1994.[19] This means that brothels no longer need to be licensed, and offenses such as a sex worker working with a sexually transmitted infection were repealed. The only offense remaining for street-based sex work is loitering or soliciting for sex work "at or near" a school, education or care service, children's service, or place of worship between the hours of 6am and 7pm, or at any time on prescribed "days of religious significance" at or near a specific religion's places of worship, being:[164]

- For Christian churches:

- Good Friday,

- Saturday before Easter Sunday,

- Easter Sunday,

- Christmas Eve,

- Christmas Day.

(Note: the prescribed days of Easter are different for Eastern Orthodox churches, whose Easter date is determined by the Julian calendar instead of the Gregorian calendar, on which the Victorian Easter public holidays and most other Christian churchs' Easter dates rely on.)

- For Muslim mosques:

- Ramadan (a period of 30 days)

- Eid al-Fitr (day after the end of Ramadan).

- For Jewish synagogues:

- Yom Kippur (a period of 2 days)

- Hanukkah (a period of 8 days).

No other "days of religious significance" have been prescribed. Other offenses exist such as a business owner or manager allowing a person aged between 18 months and 18 years of age to enter or remain in a sexual services business except if that premises is primarily used as a residence.[165]

Additionally, it is against the law to discriminate against someone, for example in rental applications or in employment, on the basis of "lawful sexual activity" under the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, and this includes sex work.[166]

History

editVictoria has a long history of debating prostitution, and was the first State to advocate regulation (as opposed to decriminalisation in New South Wales) rather than suppression of prostitution. Legislative approaches and public opinion in Victoria have gradually moved from advocating prohibition to control through regulation. While much of the activities surrounding prostitution were initially criminalised de jure, de facto the situation was one of toleration and containment of 'a necessary evil'.[167]

19th century

editLaws against prostitution existed from the founding of the State in 1851. The Vagrant Act 1852[168] included prostitution as riotous and indecent behaviour carrying a penalty of imprisonment for up to 12 months with the possibility of hard labour (Part II, s 3).[169] The Conservation of Public Health Act 1878[170] required detention and medical examination of women suspected of being prostitutes, [171] corresponding to the Contagious Diseases Acts in other parts of the British Empire. This Act was not repealed till 1916, but was relatively ineffective either in controlling venereal diseases or prostitution.[10]

The Crimes Act 1891 included specific prohibitions under PART II.—Suppression of Prostitution[172] Procurement (ss 14–17) or detention (ss 18–21) of women either through inducements or violence to work as prostitutes was prohibited, with particular reference to underage girls. The Police Offences Act 1891[173] separated riotous and indecent behaviour from prostitution, making it a specific offence for a prostitute to 'importune' a person in public (s 7(2)).[174]

Despite the laws, prostitution flourished, the block of Melbourne bounded by La Trobe Street, Spring Street, Lonsdale Street and Exhibition Street being the main red light district, and their madams were well known. An attempt at suppression in 1898 was ineffectual.[167]

Early 20th century

editThe Police Offences Act 1907[175] prohibited 'brothel keeping', leasing a premise for the purpose of a brothel, and living off prostitution (ss 5, 6). Despite a number of additional legislative responses in the early years of the century, enforcement was patchy at best. Eventually amongst drug use scandals, brothels were shut down in the 1930s. All of these laws were explicitly directed against women, other than living on the avails.

In the 1970s brothels evaded prohibition by operating as 'massage parlours', leading to pressure to regulate them, since public attitudes were moving more towards regulation rather than prohibition.[176] Initial attempts involved planning laws, when in 1975 the Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme allowed for the operation of these parlours, even though they were known to be brothels, indeed the approval process required assurances that they would not be operated as such but this was not enforced. Community concerns were loudest in the traditional Melbourne stroll area of St. Kilda.[177]

Late 20th century: From prohibition to regulation

editA Working Party was assembled in 1984 and led to the Planning (Brothel) Act 1984,[178] as a new approach. Part of the political bargaining involved in passing the act was the promise to set up a wider inquiry. The inquiry was chaired by Marcia Neave, and reported in 1985. The recommendations to allow brothels to operate legally under regulation tried to avoid some of the issues that arose in New South Wales in 1979. It was hoped that regulation would allow better control of prostitution and at the same time reduce street work. The Government attempted to implement these in the Prostitution Regulation Act 1986.[178] However, as in other States, the bill ran into considerable opposition in the upper house,[179] was extensively amended, and consequently many parts were not proclaimed. This created an incoherent patchwork approach.

21st century

editIn February 2022, Victoria passed legislation to decriminalise sex work. The Sex Work Decriminalisation Act 2021 will partially abolish street-based sex work offences and associated public health offences, remove the licensing system and move to regulate the industry through existing agencies."[180] From 1 December 2023, a sex services business will be able to operate exactly the same way as any other business in Victoria.[181]

Regulatory framework

editIn 1992 a working group was set up by the Attorney-General, which resulted in the Prostitution Control Act 1994 (PCA) [182] (now known as the Sex Work Act 1994[183]) This Act legalises and regulates the operations of brothels and escort agencies in Victoria. The difference between the two is that in the case of a brothel clients come to the place of business, which is subject to local council planning controls. In the case of an escort agency, clients phone the agency and arrange for a sex worker to come to their homes or motels. A brothel must obtain a permit from the local council (Section 21A). A brothel or escort agency must not advertise its services. (Section 18) Also, a brothel operator must not allow alcohol to be consumed at the brothel, (Section 21) nor apply for a liquor licence for the premises; nor may they allow a person under the age of 18 years to enter a brothel nor employ as a sex worker a person under 18 years of age, (Section 11A) though the age of consent in Victoria is 16 years.[184]

Owner-operated brothels and private escort workers are not required to obtain a licence, but must be registered, and escorts from brothels are permitted. If only one or two sex workers run a brothel or escort agency, which does not employ other sex workers, they also do not need a licence, but are required to be registered. However, in all other cases, the operator of a brothel or escort agency must be licensed. The licensing process enables the licensing authority to check on any criminal history of an applicant. All new brothels are limited to having no more than six rooms. However, larger brothels which existed before the Act was passed were automatically given licences and continue to operate, though cannot increase the number of rooms. Sex workers employed by licensed brothels are not required to be licensed or registered.[185] A person under 18 years is not permitted to be a sex worker (sections 5–7), and sex work must not be forced (section 8)

Amending Acts were passed in 1997 and 1999, and a report on the state of sex work in Victoria issued in 2002.[186] More substantial amendments followed in 2008.[187] The Consumer Affairs Legislation Amendment Act 2010[188] came into effect in November 2010. 'Prostitution' was replaced by 'Sex Work' throughout. The Act is now referred to as the Sex Work Act 1994. In 2011 further amendments were introduced,[167] and assented to in December 2011. In addition to the Sex Work Act 1994, it amends the Confiscation Act 1997 and the Confiscation Amendment Act 2010. The stated purposes of the Act[189] is to assign and clarify responsibility for the monitoring, investigation and enforcement of provisions of the Sex Work Act; to continue the ban on street prostitution.[190]

As part of the Sex Work Decriminalisation Act 2021, the Sex Work Act 1994 was completely repealed, effective from 1 December 2023. The only remaining consensual adult prostitution related offenses are loitering or soliciting for sex work at or near a place of worship or school at specific times, which are contained in the Summary Offenses Act 1966. Other offenses relating to children and non consensual prostitution were also transferred to other Acts. All regulatory and planning functions for brothels and other sex businesses now operate the same as any other business, with workplaces subject to WorkSafe Victoria requirements and subject to the Victorian Planning Provisions.[181]

2000s perspectives and reviews

editPremises-based sex work

editIn November 2005, 95 licensed brothels existed in Victoria and a total of 2007 small owner-operators were registered in the state (Of these, 2003 were escort agents, two were brothels, and two were combined brothels and escort agents.) Of the 95 licensed brothels, 505 rooms existed and four rooms were located in small exempt brothels. Of 157 licensed prostitution service providers (i.e. operators), 47 were brothels, 23 were escort agencies and 87 were combined brothel-escort agencies.[191] In March 2011, government data showed the existence of 98 licensed brothels in Victoria.[192]

Based on the statements of William Albon, a representative of the Australian Adult Entertainment Industry (AAEI) (formerly the Australian Adult Entertainment Association (AAEA)), the number of illegal brothels in Victoria was estimated as 400 in 2008,[193] with this estimation rising to 7,000 in 2011. In 2011 News.com.au published an estimate of 400 illegal brothels in the Melbourne metropolitan area—the article cited the news outlet's engagement with the Victorian State Government's Business Licensing Authority (BLA), the body responsible for registering owner-operated sex work businesses, but does not clarify from where or whom it obtained the estimate.[192]

However, a 2006 study conducted by the University of Melbourne, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre and Victoria's Alfred Hospital, concluded that "The number of unlicensed brothels in Melbourne is much smaller than is generally believed." The study's results presented an estimate of between 13 and 70 unlicensed brothels in Melbourne, and the method used by the researchers involved a systematically analysis of the language used in advertisements from Melbourne newspapers published in July 2006 to identify sex industry venues that were indicated a likelihood of being unlicensed. A total of 438 advertisements, representing 174 separate establishments, were analysed.[194]

Street sex work

editAn advisory group was founded in March 2001 by the Attorney-General at the time, Rob Hulls, which solely examined the issues pertaining to the City of Port Phillip, as the suburb of St. Kilda is a metropolitan location in which a significant level of street prostitution occurred. The Advisory Group consisted of residents, traders, street-based sex workers, welfare agencies, the City of Port Phillip, the State Government and Victoria Police, and released the final report after a 12-month period.[195]

The Executive Summary of the report states:

The Advisory Group seeks to use law enforcement strategies to manage and, where possible, reduce street sex work in the City of Port Phillip to the greatest extent possible, while providing support and protection for residents, traders and workers. It proposes a harm minimisation approach to create opportunities for street sex workers to leave the industry and establish arrangements under which street sex work can be conducted without workers and residents suffering violence and abuse ... A two-year trial of tolerance areas and the establishment of street worker centres represents the foundation of the package proposed by the Advisory Group. Tolerance areas would provide defined geographic zones in which clients could pick-up street sex workers. The areas would be selected following rigorous scrutiny of appropriate locations by the City of Port Phillip, and a comprehensive process of community consultation. Tolerance areas would be created as a Local Priority Policing initiative and enshrined in an accord. Ongoing monitoring would be undertaken by the City of Port Phillip Local Safety Committee.[196]

The concluding chapter of the report is entitled "The Way Forward" and lists four recommendations that were devised in light of the publication of the report. The four recommendations are listed as: a transparent process; an implementation plan; a community consultation; and the completion of an evaluation.[196]

The June 2010 Victorian Recommendations of the Drug and Crime Prevention Committee were released nearly a decade later and, according to SA:

... if implemented, will criminalise, marginalise and further hurt migrant and non- migrant sex workers in Victoria; a group who already face the most overbearing regulatory structures and health policies pertaining to sex workers in Australia, and enjoy occupational health and safety worse than that of their criminalised colleagues (Western Australia) and far behind those in a decriminalised setting (New South Wales).[197]

Alongside numerous other organisations and individuals, SA released its response to the recommendations of the Committee that were divided into two sections: 1. Opposition to all of the recommendations of the Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry 2. Recommendations from the Victorian Parliamentary Committee to the Commonwealth Government. The list of organisations in support of SA's response included Empower Foundation, Thailand; COSWAS, Collective of Sex Workers and Supporters, Taiwan; TAMPEP (European Network for HIV/STI Prevention and Health Promotion among Migrant Sex Workers); Sex Workers Outreach Project USA; Maria McMahon, Former Manager Sex Workers Outreach Project NSW and Sex Services Planning Advisory Panel, NSW Government; and Christine Harcourt, Researcher, Law & Sex Worker Health Project (LASH) for the University of NSW National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research and Faculty of Law and University of Melbourne Sexual Health Unit School of Population Health.[197]

HIV

editIn terms of HIV, a 2010 journal article by the Scarlet Alliance (SA) organisation—based on research conducted in 2008—explained that it is illegal for a HIV-positive sex worker to engage in sex work in Victoria; although, it is not illegal for a HIV-positive client to hire the services of sex workers. Additionally, according to the exact wording of the SA document, "It is not a legal requirement to disclose HIV status prior to sexual intercourse; however, it is an offence to intentionally or recklessly infect someone with HIV."[198]

Economics

editBetween 1995 and 1998, the Prostitution Control Board, a state government body, collected $991,000 Australian in prostitution licensing fees. In addition, hoteliers, casinos, taxi drivers, clothing manufacturers and retailers, newspapers, advertising agencies, and other logically related businesses profit from prostitution in the state. One prostitution business in Australia is publicly traded on the Australian stock exchange.[199]

Criticism

editCoalition Against Trafficking in Women Australia (CATWA) members Sheila Jeffreys and Mary Sullivan in a 2001 article criticised the 1984 Labor government decision to legalise prostitution in Victoria. They explained the legislative shift as follows: "The prohibition of prostitution was seen to be ineffective against a highly visible massage parlour trade (a euphemism for brothels), increasing street prostitution, criminal involvement and drug use."[191] The authors used the term "harm minimization" to describe the objective of the Labor government at the time, and the oppositional Coalition government elected in 1992 decided to continue this policy.[191][200] Sullivan and Jeffreys defined sex work as "commercial sexual violence", and argued that the aim to eliminate organised crime from the sex industry had failed.[191]

In a 2005 study Mary Sullivan of CATWA stated that prostitution businesses made revenues of A$1,780 million in 2004/5 and that the sex industry was growing at a rate of 4.6% annually (a rate higher than GDP). In the state of Victoria, there were 3.1 million instances of buying sex per year as compared with a total male population of 1.3 million men.[201]: 6

She stated that women made up 90% of the labour force in the industry in Victoria and earned, on average, A$400–$500 per week, did not receive holiday or sick pay, and worked on average four 10-hour shifts per week. According to her report, there had been an overall growth in the industry since legalisation in the mid-1980s and that with increased competition between prostitution businesses, earnings had decreased. She estimated the total number of women working in the sex trade to be 3,000 to 4,000 in the mid-1980s, opposed to 4500 women in the legal trade alone in 2005, estimating the illegal trade to be 4 to 5 times larger.[201]: 5–6

Sullivan's study stated that the sex industry was run by six large companies, which tended to control a wide array of prostitution operations, making self-employment very difficult.[201]: 8–9 She claimed brothels took 50% to 60% of the money paid by clients, and that one agency threatened a worker with a fine if she refused a customer.[201]: 7 Sullivan also alleged that legal businesses were commonly used by criminal elements as a front to launder money from human trafficking, underage prostitution, and other illicit enterprises.[201]: 14

Sullivan's claims have been widely disputed.[202][203][204][205]

Western Australia

editLike other Australian states, Western Australia has had a long history of debates and attempts to reform prostitution laws. In the absence of reform, varying degrees of toleration have existed. The current legislation is the Prostitution Act 2000,[206][207] with some offences under the Criminal Code, Health Act 1911 (addressing venereal diseases) and the Liquor Control Act 1988 (prohibiting a prostitute from being on licensed premises). Prostitution itself is legal, but many activities associated with it, such as pimping and running brothels, are illegal. Despite the fact that brothels are illegal, the state has a long history of tolerating and unofficially regulating them. Street offences are addressed in Ss. 5 and 6 of the Prostitution Act, while brothels are prohibited (including living on the earnings) under S. 190 of the Criminal Code (2004). Procuring is covered under both acts.[208]

Asian workers form a significant section of the workforce and experience a disproportionate amount of social and health problems.[209]

History

editEarly period

editLegislation addressing prostitution in Western Australia dates from the introduction of English law in 1829, specifically prohibiting bawdy houses (Interpretation Act).[208] Prostitution in Western Australia has been intimately tied to the history of gold mining.[210] In these areas a quasi-official arrangement existed between premise owners and the authorities. This was frequently justified as a harm reduction measure. Like other Australian colonies, legislation tended to be influenced by developments in Britain. The Police Act 1892 was no different, establishing penalties for soliciting or vagrancy, while the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1892 dealt with procurement. Brothel keepers were prosecuted under the Municipal Institutions Act 1895, by which all municipalities had passed brothel suppression by-laws by 1905.[211]

Twentieth century

editLaws were further strengthened by the Police Act Amendment Act 1902, and Criminal Code 1902.[10] Despite this the brothels of Kalgoorlie were legendary.[212][213] Prostitution was much debated in the media and parliament, but despite much lobbying, venereal diseases were not included in the Health Act 1911. Prostitution was also dealt with by the Criminal Code 1913. The war years and the large number of military personnel in Perth and Fremantle concentrated attention on the issue, however during much of Western Australian history, control of prostitution was largely a police affair rather than a parliamentary one, as a process of "containment", in which brothels were tolerated in exchange for a level of cooperation.[214][210] Consequently, the names and addresses of prostitutes remain recorded in the official records.[215] This policy originated in Kalgoorlie, and later appeared in Perth. The informal containment policy, dating from 1900,[208] was replaced by a more formal one in 1975. Containment was ended by the police in 2000, leaving brothels largely unregulated. Approaches reflected the ideology of the particular ruling party, as an attempt was made to replace "containment" and make control a specific parliamentary responsibility.[211][216]

There was further legislative activity in the 1980s and 1990s with the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1988 Pt. 2, Law Reform (Decriminalization Of Sodomy) Act 1989, Acts Amendment (Evidence) Act 1991, and the Criminal Law Amendment Act (No 2) 1992. The Criminal Code (s.190, s.191) made managing premises for the purpose of prostitution, living off the earnings of prostitution, or procuring a person for prostitution an offence. Reform was suggested in 1997, with the formation of a working group, and a Prostitution Control Bill was drafted in 1999 but not enacted till the Prostitution Act 2000.[206] The latter dealt principally with street soliciting, offences involving children in relation to prostitution, advertising and sponsorship.[207][211]

Gallop Government (2001–2006)

editUnder the new Australian Labor Party (ALP) Government of Geoff Gallop, elected in 2001, several prostitution Bills were introduced. In November 2002, Police Minister Michelle Roberts introduced the Prostitution Control Bill 2002[217] as a Green Bill (for public discussion).[218] Following submissions,[219] a Bill (Prostitution Control Bill 2003) was introduced in April 2003.[218][220] The latter was a bill to decriminalise prostitution, regulate brothels, introduce a licensing system and establish a Prostitution Control Board. The bill was described as a "social control model" and widely criticised.[221] It lacked sufficient support in the upper house, and eventually lapsed on 23 January 2005 on prorogation for the February election, at which the Government was returned. During this time, offences under the Police Act 1892 were repealed by passage of the Criminal Law Amendment (Simple Offences) Act 2004[222] and the Criminal Investigation (Consequential Provisions) Act 2006, transferring these offences to the Criminal Code.[208]

Carpenter Government (2006–2008)

editMuch of the debate on the subject under this government centred on the Prostitution Amendment Act 2008,[223] introduced in 2007 by Alan Carpenter's ALP Government. As a background, a working party was formed in 2006, reporting the following year.[211] Although the resulting legislation passed the upper house narrowly and received Royal Assent on 14 April 2008, it was not proclaimed before the 2008 state election, in which Carpenter and the ALP narrowly lost power in September, and therefore remained inactive, the incoming Coalition Government having vowed to repeal it in its Plan for the First 100 Days of Government.[221] The Act was based partly on the approach taken in 2003 in New Zealand (and which in turn was based on the approach in NSW). It would have decriminalised brothels and would have required certification (certification would not have applied to independent operators).[224]

Therefore, the 2000 Act continued to be in force. Brothels existed in a legal grey area, although 'containment' had officially been disbanded, in Perth in 1958 and subsequently in Kalgoorlie.[210]

Barnett Government (2008–2017)

editIn opposition the ALP criticised the lack of action on prostitution by the coalition government.[225] The debate had been reopened when the Liberal-National Barnett Government announced plans to regulate brothels in December 2009.[226] More information was announced by Attorney-General Christian Porter in June 2010.[227][228] Religious groups continued to oppose any liberalisation, as did elements within the government party[229][230] although Porter denied this.[231]

His critics stated that Porter "would accommodate the market demand for prostitution by setting up a system of licensed brothels in certain non-residential areas" and that people "should accept that prostitution will occur and legalise the trade, because we can never suppress it entirely" and that it is "like alcohol or gambling – saying it should be regulated rather than banned."[232]

Porter challenged his critics to come up with a better model and rejected the Swedish example of only criminalising clients.[233] These represent a change in thinking since an interview he gave in March 2009. However he followed through on a promise he made in early 2009 to clear the suburbs of sex work.[234]

Porter released a ministerial statement[235] and made a speech in the legislature on 25 November 2010,[236][237] inviting public submissions. The plan was immediately rejected by religious groups.[238][239]

By the time the consultation closed on 11 February 2011, 164 submissions were received, many repeating many of the arguments of the preceding years. One major submission was a comprehensive review of prostitution in Western Australia by a team from the University of NSW.[208] This time Porter found himself criticised by both sides of the 2007 debate, for instance churches that supported the Coalition position in opposition, now criticised them,[240] while sex worker groups that supported the Carpenter proposals continued to oppose coalition policies,[241][242] as did health groups.[243]

Prostitution Bill 2011

editOn 14 June 2011 the Minister made a "Green Bill"[244] (draft legislation) available for public comment over a six-week period.[245][246] Porter explained the purpose of the legislation thus: "The Prostitution Bill 2011 will not only ban brothels from residential areas but also ensure appropriate regulatory and licensing schemes are in place for those very limited non-residential areas where prostitution will be permitted and heavily regulated." A FAQ sheet was also developed.[247] Publication of the Bill did not shift the debate—which remained deeply polarised, with any legalisation bitterly opposed by conservative religious groups—despite Porter's assurances that his government did not condone sex work.[248][249][250] Sex Workers and health organisations remained just as committed to opposing the proposals.[251][252]

Following consultation, the government announced a series of changes to the bill that represented compromises with its critics,[253] and the changes were then introduced into parliament on 3 November 2011,[254] where it received a first and second reading.[255]

Sex workers continued to stand in opposition.[256][257] Significantly, the opposition Labor Party opposed the bill,[258] both political parties agreeing on the need to decriminalise the indoor market, but differing in approach. Since the government was in a minority, it required the support of several independent members to ensure passage through the Legislative Assembly.[259] In practice, it proved difficult to muster sufficient public support, and the Bill did not attract sufficient support in parliament either. Porter left State politics in June 2012, being succeeded by Michael Mischin. Mischin admitted it would be unlikely that the bill would pass in that session.[260] This proved to be true, as the legislature was prorogued on 30 January 2013, pending the general election on 9 March, and thus all bills lapsed.[261]

The Barnett government was returned in that election with a clear majority, but stated it would not reintroduce the previous bill and that the subject was a low priority. Meanwhile, sex workers continued to push for decriminalisation.[262] A division exists within the government party, with some members such as Nick Goiran threatening 'civil war'.[263]

McGowan Government (2017–)

editIn the election campaign of 2017, prostitution law reform was among the topics debated, and the Barnett government defeated with a return to power of the ALP. Public discussion of reform has continued since, with lobbying on both sides of the question,[264] while a further review of the industry, following up on the 2010 (LASH) report,[208] continued to recommend decriminalisation (The Law and Sex worker Health, LASH reports).[265][266][267]

Other minor territories of Australia

editChristmas Island

editChristmas Island is a former British colony, which was administered as part of the Colony of Singapore. The laws of Singapore, including prostitution law, were based on British law. In 1958, the sovereignty of the island was transferred to Australia. The ‘laws of the Colony of Singapore’ continued to be the law of the territory.[268] The Territories Law Reform Act 1992 decreed that Australian federal law and the state laws of Western Australia be applicable to the Indian Ocean Territories, of which Christmas Island is a part.[268]

For the current situation see Western Australia.

Cocos (Keeling) Islands

editCocos (Keeling) Islands were, like Christmas Island, a British colony and part of the Colony of Singapore. After transfer of sovereignty to Australia in 1955, Singapore's colonial law was still in force on the islands until 1992.[268] The Territories Law Reform Act 1992 made Australian federal law and the state laws of Western Australia applicable to the islands.[268]

For the current situation see Western Australia.

Norfolk Island

editPreviously a self-governing Australian territory, the Norfolk Island Applied Laws Ordinance 2016 applied Australian federal law and the state laws of New South Wales to Norfolk Island.[269]

For the current situation see New South Wales.

See also

edit- History of Australia

- Daily Planet brothel

- Scarlet Alliance

- Convict women in Australia

- R v McLean & Trinh, trial for the murder of two prostitutes in the Northern Territory

References

edit- ^ a b c "The Legal Status of Sex Work Across Australia". Sydney Criminal Lawyers. 1 May 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Tasmania sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Western Australia sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "South Australia sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Australian Capital Territory sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Northern Territory sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "New South Wales sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Queensland sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Victoria's sex work laws | Scarlet Alliance". scarletalliance.org.au. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Frances 1994.

- ^ a b Carpenter & Hayes 2014.

- ^ a b Pinto et al 1990.

- ^ Aroney, Eurydice; Crofts, Penny (30 April 2019). "How Sex Worker Activism Influenced the Decriminalisation of Sex Work in NSW, Australia". International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. 8 (2): 50–67. doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i2.955. hdl:10453/133742. ISSN 2202-8005.

- ^ a b UNData 2019.

- ^ "View - Queensland Legislation - Queensland Government".

- ^ Messenger, Andrew (2 May 2024). "Sex work decriminalised in Queensland after decades of campaigning". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Parliament of Queensland. "Report No. 4, 57th Parliament - Criminal Code (Decriminalising Sex Work) and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2024". www.parliament.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Prostitution Licensing Authority (28 April 2023). "Sex Work Industry Review". Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Decriminalising sex work in Victoria | Victorian Government". www.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "NT Parliament votes to decriminalise sex work". ABC News. 26 November 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perkins 1991.

- ^ Saunders 1995.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (1994). "The Making of Prostitutes in Japan: The Karayuki-San". Social Justice. 21 (2). Social Justice/Global Options: 161–84. JSTOR 29766813.

- ^ Hong, Regina (8 July 2021). "Picturing the past: Postcards and the pre-war Japanese in Singapore". ARIscope Home - Asia Research Institute, NUS.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (1994). "The Making of Prostitutes in Japan: The Karayuki-San". Social Justice. 21 (2): 161–84. JSTOR 29766813.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (26 August 2012). "世界かWomen, Overseas Sex Work and Globalization in Meiji Japan 明治日本における女性,国外性労働、海外進出". Japan Focus: The Asia-Pacific Journal. 10 (35).

- ^ Lay, Belmont (18 May 2016). "Thousands of Japanese women worked as prostitutes in S'pore in late 1800s, early 1900s". Mothership.SG.

- ^ Isono, Tomotaka (13 May 2012). ""Karayuki-san" and "Japayuki-san"". The North American Post: Seattle Japanese Community.

- ^ Sissons, D. C. S. (1977). "Karayuki-san: Japanese prostitutes in Australia, 1887–1916 (I & II)" (PDF). Historical Studies. 17 (68). Taylor & Francis Ltd: 323–341. doi:10.1080/10314617708595555.

- ^ Sone, Sachiko (January 1990). The karayuki-san of Asia, 1868-1938 : the role of prostitutes overseas in Japanese economic and social development (Master's Thesis).

- ^ Rissel et al 2003.

- ^ Hyo-sik, Lee (14 November 2011). "Over 1,000 Korean women are prostitutes in Australia". Korea Times. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ McKenzie, Nick (2 November 2022). "Australian colleges identified in allegedly helping women enter country to work in sex industry". The Age. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Scarlet Alliance 2016.

- ^ a b Maginn 2013.

- ^ Scott et al 2012.

- ^ Joint Committee 2006.

- ^ Criminal Code Amendment (Slavery and Sexual Servitude) Act 1999 (Cth)

- ^ OHCHR 2000.

- ^ ACT SWA 1992.

- ^ a b ORS 2011.

- ^ "Prostitution Amendment Act 2002 (ACT)" (PDF).

- ^ Justice and Community Safety Legislation Amendment Act 2011 (ACT).

- ^ Police Offences Act 1930 (ACT).

- ^ Collaery 1992.

- ^ "Sex trade laws under review. ABC News 1 Oct 2010". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 September 2010.

- ^ Inquiry into Prostitution Act: Terms of Reference Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Inquiry into Prostitution Act: Submissions Archived 7 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Scarlet Alliance submission to the Standing Committee on Justice 2011". 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b Sex trade eyes the suburbs. Canberra Times March 2011 Archived 9 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ACL appears at ACT prostitution inquiry. ACL 11 May 2011". Australianchristianlobby.org.au. 12 May 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011.

- ^ Norma, Caroline. "Review into prostitution must benefit women not business ABC 21 March 2011". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Coalition Against Trafficking in Women Australia Archived 6 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Submission of the Catholic Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn" (PDF). www.parliament.act.gov.au. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Jeffreys, Elena (19 May 2011). "Don't use the Swedish model for ACT sex workers. Canberra Times 19 May 2011". Nothing-about-us-without-us.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ Evans, Kate (8 April 2011). "No exit programs for Canberra sex workers". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Dyett, Kathleen (23 March 2011). "Unregulated sex industry 'hard to gauge'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Hansard committee transcripts: Justice 13 July 2011" (PDF).