The Viruses Portal

Welcome!

Viruses are small infectious agents that can replicate only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all forms of life, including animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and archaea. They are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity, with millions of different types, although only about 6,000 viruses have been described in detail. Some viruses cause disease in humans, and others are responsible for economically important diseases of livestock and crops.

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of genetic material, which can be either DNA or RNA, wrapped in a protein coat called the capsid; some viruses also have an outer lipid envelope. The capsid can take simple helical or icosahedral forms, or more complex structures. The average virus is about 1/100 the size of the average bacterium, and most are too small to be seen directly with an optical microscope.

The origins of viruses are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids, others from bacteria. Viruses are sometimes considered to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce and evolve through natural selection. However they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life".

Selected disease

Shingles, or herpes zoster, is a painful skin rash with blisters that, characteristically, occurs in a stripe limited to just one side of the body. The rash usually heals within 2–5 weeks, but around one in five people experience residual nerve pain for months or years.

Shingles is caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), an alpha-herpesvirus. Initial VZV infection usually occurs in childhood causing chickenpox. After this resolves, the virus is not eliminated from the body, but remains latent in the nerve cell bodies of the dorsal root or trigeminal ganglia, without causing symptoms. Years or decades later, shingles occurs when virions in a single ganglion reactivate, travel down nerve fibres and infect the skin around the nerve. The shingles rash is restricted to the area of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve, termed the dermatome. Exactly how VZV remains latent in the body, and subsequently reactivates, is unclear.

Around a third of the population will develop shingles. Repeated episodes are rare. In the United States, about half the cases occur in people aged 50 years or older. Vaccination at least halves the risk, and prompt treatment with aciclovir or related antiviral drugs can reduce the severity and duration of the rash.

Selected image

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu survived smallpox, and popularised the Turkish practice of variolation against the disease in western Europe in the 1720s.

Credit: Jean-Étienne Liotard (c. 1756)

In the news

26 February: In the ongoing pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), more than 110 million confirmed cases, including 2.5 million deaths, have been documented globally since the outbreak began in December 2019. WHO

18 February: Seven asymptomatic cases of avian influenza A subtype H5N8, the first documented H5N8 cases in humans, are reported in Astrakhan Oblast, Russia, after more than 100,0000 hens died on a poultry farm in December. WHO

14 February: Seven cases of Ebola virus disease are reported in Gouécké, south-east Guinea. WHO

7 February: A case of Ebola virus disease is detected in North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. WHO

4 February: An outbreak of Rift Valley fever is ongoing in Kenya, with 32 human cases, including 11 deaths, since the outbreak started in November. WHO

21 November: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gives emergency-use authorisation to casirivimab/imdevimab, a combination monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for non-hospitalised people twelve years and over with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, after granting emergency-use authorisation to the single mAb bamlanivimab earlier in the month. FDA 1, 2

18 November: The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Équateur Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, which started in June, has been declared over; a total of 130 cases were recorded, with 55 deaths. UN

Selected article

Virus classification is the process of naming viruses and placing them into a taxonomic system. They are mainly classified by phenotypic characteristics, such as morphology, nucleic acid type, mode of replication, host organisms and the type of disease they cause.

Two schemes are in common use. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), established in the early 1970s, classifies viruses into taxa (groups) similar to the biological classification used for cellular organisms, which reflect viruses believed to have a common ancestor. As of 2019, 9 kingdoms, 16 phyla, 36 classes, 55 orders, 168 families, 1,421 genera and 6,589 species of viruses have been defined. Since 2018, viruses have also been classified into higher-level taxa called realms. Four realms are defined, as of 2020, encompassing almost all RNA viruses; some DNA viruses have yet to be assigned a realm.

The older Baltimore classification (pictured), proposed in 1971 by David Baltimore, places viruses into seven groups (I–VII) based on their nucleic acid type, number of strands and sense, as well as the method the virus uses to generate mRNA. There is some concordance between Baltimore groups and the higher levels of the ICTV scheme.

Selected outbreak

The 1918–20 influenza pandemic, the first of the two involving H1N1 influenza virus, was unusually deadly. It infected 500 million people across the entire globe, with a death toll of 50–100 million (3–5% of the world's population), making it one of the deadliest natural disasters of human history. It has also been implicated in the outbreak of encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s. Despite the nickname "Spanish flu", the pandemic's geographic origin is unknown.

Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill young, elderly or already weakened patients; in contrast this predominantly killed healthy young adults. Contemporary medical reports suggest that malnourishment, overcrowded medical facilities and poor hygiene promoted fatal bacterial pneumonia. Some research suggests that the virus might have killed through a cytokine storm, an overreaction of the body's immune system. This would mean the strong immune reactions of young adults resulted in a more severe disease than the weaker immune systems of children and older adults.

Selected quotation

| “ | What is needed ... is a new inquiry at international level ... to investigate a reconciliation between the right to health and the right of authors to proper protection for their inventions. At the moment, all the eggs are in the basket of the authors, and it’s not really a proportionate balance. | ” |

—Michael Kirby on the cost of antiviral drugs

Recommended articles

Viruses & Subviral agents: bat virome • elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus • HIV • introduction to viruses![]() • Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus

• Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus![]() • virus

• virus![]()

Diseases: colony collapse disorder • common cold • croup • dengue fever![]() • gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza

• gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza![]() • meningitis

• meningitis![]() • myxomatosis • polio

• myxomatosis • polio![]() • pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

• pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

Epidemiology & Interventions: 2007 Bernard Matthews H5N1 outbreak • Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations • Disease X • 2009 flu pandemic • HIV/AIDS in Malawi • polio vaccine • Spanish flu • West African Ebola virus epidemic

Virus–Host interactions: antibody • host • immune system![]() • parasitism • RNA interference

• parasitism • RNA interference![]()

Methodology: metagenomics

Social & Media: And the Band Played On • Contagion • "Flu Season" • Frank's Cock![]() • Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa

• Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa![]() • social history of viruses

• social history of viruses![]() • "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

• "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

People: Brownie Mary • Macfarlane Burnet![]() • Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C

• Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C![]() • HIV-positive people

• HIV-positive people![]() • Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock

• Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock![]() • poliomyelitis survivors

• poliomyelitis survivors![]() • Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White

• Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White![]()

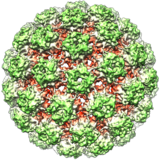

Selected virus

Papillomaviruses are small non-enveloped DNA viruses that make up the Papillomaviridae family. Their circular double-stranded genome is around 8000 nucleotides long. The icosahedral capsid is 55–60 nm in diameter. They infect humans, other mammals and some other vertebrates including birds, snakes, turtles and fish. Around a hundred species are classified into 53 genera. All papillomaviruses replicate exclusively in epithelial cells of stratified squamous epithelium, which forms the skin and some mucosal surfaces, including the lining of the mouth, airways, genitals and anus.

Infection by most papillomaviruses is either asymptomatic or causes small benign tumours known as warts or papillomas. Francis Peyton Rous showed in 1935 that the Shope papilloma virus could cause skin cancer in rabbits – the first time that a virus was shown to cause cancer in mammals – and papillomas caused by some virus types, including human papillomavirus 16 and 18, carry a risk of becoming cancerous if the infection persists. Papillomaviruses are associated with cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, oropharynx and anus in humans.

Did you know?

- ...that coccolithovirus (pictured, arrow), a giant double-stranded DNA virus, has 472 protein-coding genes, and was the largest known marine virus by genome until the 2013 discovery of Pandoravirus salinus?

- ...that Tony Minson developed a new way of disabling viruses for vaccines?

- ...that the Oscar Award-nominated film The Final Inch, a documentary about efforts to eradicate the poliovirus, is the first film project from Google's philanthropic division Google.org?

- ...that a June 5, 1981, report by Joel Weisman in MMWR about five gay men with an unusual illness is recognized as the start of the AIDS pandemic and "the first report on AIDS in the medical literature"?

- ...that elastomeric respirators are used not only to protect against COVID-19 and tear gas, but also as fashion items?

Selected biography

Peter Piot (born 17 February 1949) is a Belgian virologist and public health specialist, known for his work on Ebola virus and HIV.

During the first outbreak of Ebola in Yambuku, Zaire in 1976, Piot was one of a team that discovered the filovirus in a blood sample. He and his colleagues travelled to Zaire to help to control the outbreak, and showed that the virus is transmitted via blood and during preparation of bodies for burial. He advised WHO during the West African Ebola epidemic of 2014–16.

In the 1980s, Piot participated in collaborative projects in Burundi, Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, Tanzania and Zaire, including Project SIDA in Kinshasa, the first international project on AIDS in Africa, which provided the foundations for understanding HIV infection in that continent. He was the founding director of UNAIDS, and has served as president of the International AIDS Society and assistant director of the WHO Global HIV/AIDS Programme. As of 2020, he directs the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

In this month

1 September 1910: Peyton Rous shows that a sarcoma of chickens, subsequently associated with Rous sarcoma virus, is transmissible

3 September 1917: Discovery of bacteriophage of Shigella by Félix d'Herelle

8 September 1976: Death of Mabalo Lokela, the first known case of Ebola virus

8 September 2015: Discovery of giant virus Mollivirus sibericum in Siberian permafrost

11 September 1978: Janet Parker was the last person to die of smallpox

12 September 1957: Interferon discovered by Alick Isaacs and Jean Lindenmann

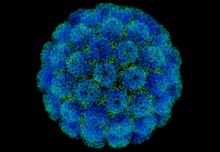

12 September 1985: Structure of human rhinovirus 14 (pictured) solved by Michael Rossmann and colleagues, the first atomic-level structure of an animal virus

17 September 1999: Jesse Gelsinger died in a clinical trial of gene therapy using an adenovirus vector, the first known death due to gene therapy

20 September 2015: Wild poliovirus type 2 declared eradicated

26 September 1997: Combivir (zidovudine/lamivudine) approved; first combination antiretroviral

27 September 1985: Structure of poliovirus solved by Jim Hogle and colleagues

28 September 2007: First World Rabies Day is held

Selected intervention

Influenza vaccines include live attenuated and inactivated forms. Inactivated vaccines contain three or four different viral strains selected by the World Health Organization to cover influenza A H1N1 and H3N2, as well as influenza B, and are usually administered by intramuscular injection. The live attenuated influenza vaccine contains a cold-adapted strain and is given as a nasal spray. Most influenza vaccine strains are cultivated in fertilised chicken eggs (pictured), a technique developed in the 1950s; others are grown in cell cultures, and some vaccines contain recombinant proteins. Annual vaccination is recommended for high-risk groups and, in some countries, for all those over six months. As the influenza virus changes rapidly by antigenic drift, new versions of the vaccine are developed twice a year, which differ in effectiveness depending on how well they match the circulating strains. Despite considerable research effort for decades, no effective universal influenza vaccine has been identified. A 2018 meta-analysis found that vaccination in healthy adults decreased confirmed cases of influenza from about 2.4% to 1.1%. However, the effectiveness is uncertain in those over 65 years old, one of the groups at highest risk of serious complications.

Subcategories

Subcategories of virology:

Topics

Things to do

- Comment on what you like and dislike about this portal

- Join the Viruses WikiProject

- Tag articles on viruses and virology with the project banner by adding {{WikiProject Viruses}} to the talk page

- Assess unassessed articles against the project standards

- Create requested pages: red-linked viruses | red-linked virus genera

- Expand a virus stub into a full article, adding images, citations, references and taxoboxes, following the project guidelines

- Create a new article (or expand an old one 5-fold) and nominate it for the main page Did You Know? section

- Improve a B-class article and nominate it for Good Article

or Featured Article

or Featured Article status

status - Suggest articles, pictures, interesting facts, events and news to be featured here on the portal

WikiProjects & Portals

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

Medicine • Microbiology • Molecular & Cellular Biology • Veterinary Medicine

Related PortalsAssociated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikispecies

Directory of species -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus