Pomalidomide, sold under the brand names Pomalyst and Imnovid,[7][8] is an anti-cancer medication used for the treatment of multiple myeloma and AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma.[7]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pomalyst, Imnovid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a613030 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 73% (at least)[9] |

| Protein binding | 12–44% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP1A2- and CYP3A4-mediated; some minor contributions by CYP2C19 and CYP2D6) |

| Elimination half-life | 7.5 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (73%), faeces (15%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.232.884 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H11N3O4 |

| Molar mass | 273.248 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

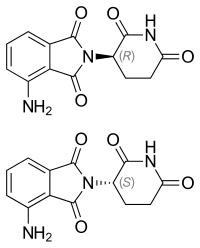

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Pomalidomide was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2013,[10] and in the European Union in August 2013.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[11]

Medical uses

editIn the European Union, pomalidomide, in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone, is indicated in the treatment of adults with multiple myeloma who have received at least one prior treatment regimen including lenalidomide;[8] and in combination with dexamethasone is indicated in the treatment of adults with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least two prior treatment regimens, including both lenalidomide and bortezomib, and have demonstrated disease progression on the last therapy.[8]

In the United States, pomalidomide is indicated, in combination with dexamethasone, for people with multiple myeloma who have received at least two prior therapies including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor and have demonstrated disease progression on or within 60 days of completion of the last therapy;[12] and is indicated for people with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma after failure of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) or in people with Kaposi sarcoma who are HIV-negative.[12][13][14][15]

Origin and development

editThe parent compound of pomalidomide, thalidomide, was originally discovered to inhibit angiogenesis in 1994.[16] Based upon this discovery, thalidomide was taken into clinical trials for cancer, leading to its ultimate FDA approval for multiple myeloma.[17] Structure-activity studies revealed that amino substituted thalidomide had improved antitumor activity, which was due to its ability to directly inhibit both the tumor cell and vascular compartments of myeloma cancers.[18] This dual activity of pomalidomide makes it more efficacious than thalidomide in vitro and in vivo.[19]

Mechanism of action

editPomalidomide directly inhibits angiogenesis and myeloma cell growth. This dual effect is central to its activity in myeloma, rather than other pathways such as TNF alpha inhibition, since potent TNF inhibitors including rolipram and pentoxifylline do not inhibit myeloma cell growth or angiogenesis.[18] Upregulation of interferon gamma, IL-2 and IL-10 as well as downregulation of IL-6 have been reported for pomalidomide. These changes may contribute to pomalidomide's anti-angiogenic and anti-myeloma activities.

Like thalidomide, pomalidomide works as a cereblon E3 ligase modulator.[20]

Side effects

editPomalidomide can cause harm to unborn babies when administered during pregnancy.[8]

Pomalidomide is present in the semen of people receiving the drug.[8][7]

Clinical trials

editPhase I trial results showed tolerable side effects.[21]

Phase II clinical trials for multiple myeloma and myelofibrosis reported 'promising results'.[22][23]

Phase III results showed significant extension of progression-free survival, and overall survival (median 11.9 months vs. 7.8 months; p = 0.0002) in patients taking pomalidomide and dexamethasone vs. dexamethasone alone.[24]

References

edit- ^ "Pomalidomide (Pomalyst) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 14 May 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "Pomalidomide Medicianz/ Pomalimed/ Pomalidomide Medsurge (Medicianz Healthcare Pty Ltd)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 5 December 2022. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2014". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "Pomalyst Product information". Health Canada. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Imnovid 1 mg hard capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Pomalyst- pomalidomide capsule". DailyMed. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Imnovid EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Imnovid 1 mg Hard Capsules. Summary of Product Characteristics. 5.2 Pharmacokinetic properties" (PDF). Celgene Europe Ltd. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Pomalyst (pomalidomide) Capsules NDA #204026". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 8 February 2013. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "2020 First Generic Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 23 February 2021. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Pomalidomide". National Cancer Institute. 13 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FDA grants accelerated approval to pomalidomide for Kaposi sarcoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FDA approves pomalidomide for AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma". National Cancer Institute (Press release). 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Cancer Accelerated Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 1 May 2023. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ D'Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J (April 1994). "Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (9): 4082–5. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.4082D. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. JSTOR 2364596. PMC 43727. PMID 7513432.

- ^ {{cite news| vauthors = Altman D |title=From Thalidomide to Pomalyst: Better Living Through Chemistry|url=https://www.damatolab.com/from-thalidomide-to-pomalyst

- ^ a b D'Amato RJ, Lentzsch S, Anderson KC, Rogers MS (December 2001). "Mechanism of action of thalidomide and 3-aminothalidomide in multiple myeloma". Seminars in Oncology. 28 (6): 597–601. doi:10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90031-4. PMID 11740816.

- ^ Lentzsch S, Rogers MS, LeBlanc R, Birsner AE, Shah JH, Treston AM, et al. (April 2002). "S-3-Amino-phthalimido-glutarimide inhibits angiogenesis and growth of B-cell neoplasias in mice". Cancer Research. 62 (8): 2300–5. PMID 11956087.

- ^ Asatsuma-Okumura T, Ito T, Handa H (October 2019). "Molecular mechanisms of cereblon-based drugs". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 202: 132–139. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.06.004. PMID 31202702.

- ^ Streetly MJ, Gyertson K, Daniel Y, Zeldis JB, Kazmi M, Schey SA (April 2008). "Alternate day pomalidomide retains anti-myeloma effect with reduced adverse events and evidence of in vivo immunomodulation". British Journal of Haematology. 141 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07013.x. PMID 18324965. S2CID 37073246.

- ^ "Promising Results From 2 Trials Highlighting Pomalidomide Presented At ASH" (Press release). Celgene. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Tefferi A (8 December 2008). Pomalidomide Therapy in Anemic Patients with Myelofibrosis: Results from a Phase-2 Randomized Multicenter Study. 50th ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition. San Francisco. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Miguel JS, Weisel K, Moreau P, Lacy M, Song K, Delforge M, et al. (September 2013). "Pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone versus high-dose dexamethasone alone for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM-003): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial" (PDF). The Lancet. Oncology. 14 (11): 1055–1066. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70380-2. hdl:2318/150538. PMID 24007748. S2CID 4526729. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2019.