The Free Papua Movement or Free Papua Organization (Indonesian: Organisasi Papua Merdeka, OPM) is a name given to an independence movement based on Western New Guinea, seeking secession of the territory currently under Indonesian administration. The territory is currently divided into six Indonesian provinces of Central Papua, Highland Papua, Papua, South Papua, Southwest Papua, and West Papua, also formerly known as Papua, Irian Jaya and West Irian.[5]

| Free Papua Movement | |

|---|---|

| Organisasi Papua Merdeka, OPM | |

| Leaders | Jacob Hendrik Prai (until 2022) |

| Dates of operation | 1 December 1963 – present |

| Active regions | Predominantly in Central Papua and Highland Papua; less prominent in Papua, South Papua, Southwest Papua, and West Papua |

| Ideology | Papuan nationalism Revolutionary nationalism Separation from Indonesia Anti-colonialism Anti-imperialism Anti-capitalism[1] |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

| Battles and wars | Papua conflict |

| Designated as a terrorist group by | |

The movement consists of three elements: a disparate group of armed units each with limited territorial control with no single commander; several groups in the territory that conduct demonstrations and protests; and a small group of leaders based abroad that raise awareness of issues in the territory whilst striving for international support for independence.[5]

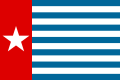

Since its inception, the OPM has attempted diplomatic dialogue, conducted Morning Star flag-raising ceremonies, and undertaken militant actions as part of the Papua conflict. Supporters routinely display the Morning Star flag and other symbols of Papuan unity, such as the national anthem "Hai Tanahku Papua" and a national coat of arms, which had been adopted in the period 1961 until Indonesian administration began in May 1963 under the New York Agreement.[6] Beginning in 2021, the movement is considered as a "Terrorist and Separatist Organisation" (Indonesian: Kelompok Teroris dan Separatis) in Indonesia, and its activities have incurred charges of treason and terrorism.[3]

History

editDuring World War II, the Netherlands East Indies (later Indonesia) were guided by Sukarno to supply oil for the Japanese war effort and subsequently declared independence as the Republic of Indonesia on 17 August 1945. The Netherlands New Guinea (Western New Guinea, then a part of the Netherlands East Indies) and Australian administered territories of Papua and British New Guinea resisted Japanese control and were allies with the American and Australian forces during the Pacific War.

The pre-war relationship of the Netherlands and its New Guinea colony was replaced with the promotion of Papuan civil and other services[7] until Indonesian administration began in 1963. Though there was agreement between Australia and the Netherlands by 1957 that it would be preferable for their territories to unite for independence, the lack of development in the Australian territories and the interests of the United States kept the two regions separate. The OPM was founded in December 1963, with the announcement that "We do not want modern life! We refuse any kinds of development: religious groups, aid agencies, and governmental organizations just Leave Us Alone! [sic]"[8] Originally the group was a nonviolent spiritual movement based in cargoism and was led by Aser Demotekay, former head of Demta District. His policy of nonviolence and cooperation with Indonesian government, led to the creation of a more radical splinter group under Jacob Prai, former student of Demotekay.[9]

Netherlands New Guinea held elections in January 1961 and a New Guinea Council was inaugurated in April 1961. However, in Washington, D.C. there was a desire for Indonesia to release CIA pilot Allen Pope,[10] and there was a proposal for United Nations trusteeship of West New Guinea,[11] Indonesian President Sukarno said he was willing 'to borrow the hand of the United Nations to transfer the territory to Indonesia',[12] and the National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy began to lobby U.S. President John F. Kennedy to get the administration of West New Guinea transferred to Indonesia.[13] The resulting New York Agreement was drafted by Robert Kennedy and signed by the Netherlands and Indonesia before being approved subject to the Charter of the United Nations article 85[14] in General Assembly resolution 1752[15] on 21 September 1962.

Although the Netherlands had insisted the West New Guinea people be allowed self-determination in accord with the United Nations charter and General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV) which was to be called the "Act of Free Choice"; the New York Agreement instead provided a seven year delay and gave the United Nations no authority to supervise the act.[16] Separatist groups raise the West Papua Morning Star flag each year on 1 December, which they call "Papuan independence day". An Indonesian police officer speculated that people doing this could be charged with the crime of treason, which carries the penalty of imprisonment for seven to twenty years in Indonesia.[17]

In October 1968, Nicolaas Jouwe, member of the New Guinea Council and of the National Committee elected by the Council in 1962, lobbied the United Nations claiming 30,000 Indonesian troops and thousands of Indonesian civil servants were repressing the Papuan population.[18] According to US Ambassador Galbraith, the Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik also believed the Indonesian military was the cause of problems in the territory and the number of troops should be reduced by at least one half. Ambassador Galbraith further described the OPM to "represent an amorphous mass of anti-Indonesia sentiment" and that "possibly 85 to 90 percent [of Papuans], are in sympathy with the Free Papua cause or at least intensely dislike Indonesians".[19]

Indonesian Brigadier General Sarwo Edhie oversaw the design and conduct of the Act of Free Choice which took place from 14 July to 2 August 1969. The United Nations representative Ambassador Oritiz Sanz arrived on 22 August 1968 and made repeated requests for Indonesia to allow a one man, one vote system (a process known as a referendum or plebiscite) but these requests were refused on the grounds that such activity was not specified nor requested by the 1962 New York Agreement.[20][21] One thousand and twenty five Papuan elders were selected from and instructed on the required procedure as specified by the article 1962 New York Agreement. The result was a consensus for integration into Indonesia.

Republic of West Papua Declaration

editIn response, Nicolaas Jouwe and two OPM commanders, Seth Jafeth Roemkorem and Jacob Hendrik Prai, planned to announce Papuan Independence in 1971. On 1 July 1971 Roemkorem and Prai declared a "Republic of West Papua", and drafted a constitution in 'Victoria Headquarters'.

Conflicts over strategy and suspicion between Roemkorem and Prai soon initiated a split of the OPM into two factions; Prai left in March 1976 and by December founded 'Defender of Truth', and TPN led by Roemkorem in 'Victoria Headquarters'.[22] This greatly weakened OPM's ability as a centralized combat force. It remains widely used, however, invoked by both contemporary fighters and domestic and expatriate political activists.

Activities

edit1970s

editStarting from 1976, officials at mining company Freeport Indonesia received letters from the OPM threatening the company and demanding assistance in a planned uprising in the spring. The company refused to cooperate with OPM. From July until 7 September 1977, OPM insurgents carried out their threats against Freeport and cut slurry and fuel pipelines, slashed telephone and power cables, burned down a warehouse, and detonated explosives at various facilities. Freeport estimated the damage at $US123,871.23.[23]

1980s

editIn 1982 a OPM Revolutionary Council (OPMRC) was established, and under the chairmanship of Moses Werror the OPMRC has sought independence through a campaign of international diplomacy. OPMRC aims to obtain international recognition for West Papuan independence through international forums such as the United Nations, The Non-Aligned Movement of Nations, The South Pacific Forum and The Association of South East Asian Nations.

In 1984 OPM staged an attack on Jayapura, the provincial capital and a city dominated by non-Melanesian Indonesians. The attack was quickly repelled by the Indonesian military, who followed it with broader counter-insurgency activity. This triggered an exodus of Papuan refugees, apparently supported by the OPM, into camps across the border in Papua New Guinea.

On 14 February 1986, Freeport Indonesia received information that the OPM was again becoming active in their area, and that some of Freeport's employees were OPM members or sympathisers. On 18 February, a letter signed by a "Rebel General" warned that "On Wed. 19th, there will be some rain on Tembagapura". At around 22:00 that night several unidentified people cut Freeport's slurry and fuel pipelines by hacksaw, causing "a substantial loss of slurry, containing copper, silver and gold ores and diesel fuel." Additionally, the saboteurs set fire along the breaks in the fuel line, and shot at police that tried to approach the fires. On 14 April of that same year, OPM insurgents cut more pipelines, slashed electric wires, vandalised plumbing, and burned equipment tyres. Repair crews were attacked by OPM gunfire as they approached the sites of the damage, so Freeport requested police and military assistance.[23]

1990s

editIn separate incidents in January and August 1996, OPM captured European and Indonesian hostages; first from a research group and later from a logging camp. Two hostages from the former group were killed and the rest were released.

In July 1998, the OPM raised their independence flag at the Kota Biak water tower on the island of Biak. They stayed there for the following few days before the Indonesian Military broke up the group. Filep Karma was among those arrested.[24]

2000 to 2019

editIn 2009, an OPM command group led by Goliath Tabuni in Puncak Jaya Regency was featured on an undercover report about the West Papuan independence movement.[25]

On 24 October 2011, Adj. Comr. Dominggus Oktavianus Awes, the Mulia Police chief, was shot by unknown assailants at Mulia Airport in Puncak Jaya regency. The National Police of Indonesia alleged that the perpetrators were members of the Free Papua Movement (OPM) separatist group. The series of attacks prompted deployments of more personnel to Papua.[26]

On 21 January 2012, armed men, believed to be members of OPM, shot and killed a civilian who was running a roadside kiosk. He was a transmigrant from West Sumatra.[27]

On 8 January 2012, OPM conducted an attack on a public bus which caused the death of three civilians and one member of an Indonesian security force. Four others were also injured.[28]

On 31 January 2012, an OPM member was caught carrying 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of drugs on the Indonesian – Papua New Guinea Border. It was alleged that the drugs were intended to be sold in the city of Jayapura.[29]

On 8 April 2012, Indonesian media sources alleged that armed members of OPM carried out an attack on a civilian aircraft flown by Trigana Air on a scheduled service after it landed and was taxiing towards an apron at Mulia Airport on Puncak Jaya, Papua. Five armed OPM militants suddenly opened fire on the moving plane, causing it to go out of control and crash into a building. One person who died, Leiron Kogoya, a journalist for Papua Pos, had suffered a neck gunshot wound. Amongst those wounded were the pilot, Beby Astek, and co-pilot, Willy Resubun, both wounded by shrapnel; Yanti Korwa, a housewife who was hurt by shrapnel on her right arm, and her four-year-old infant, Pako Korwa, who was afflicted by shrapnel on his left hand.[30] In response to the allegations, West Papuan media source denied that the OPM was responsible for the attack, alleging that the Indonesian military had attacked the plane as a part of a false flag operation.[31]

In December 2012, an Australian would-be mercenary, who was trained by a military/police security firm in Ukraine,[32] was arrested in Australia for planning to train the OPM.[33] He later pleaded guilty to training in the use of arms or explosives with the intention of committing an offence against the Crimes (Foreign Incursions and Recruitment) Act 1978.[34]

On 26 April 2018, a Polish OPM sympathizer and a far-right nationalist was arrested in Wamena along with four Papuans who police described as linked to "armed criminal groups" and was charged with treason.[35] He later sentenced five year in prison.[36]

On 1 December 2018, an armed group with ties to OPM kidnapped 25 civilian construction workers in Nduga regency, Papua. The following day, the group killed 19 of the workers and a soldier.[37] One of construction workers had allegedly photographed the group raising the Morning Star flag at an independence celebration - considered illegal acts by Indonesian authorities.[38] The construction workers were building a part of the Trans Papua highway that aims to connect remote communities in Papua.[39] A few days after the incident, the OPM allegedly sent an open letter to Indonesian president Joko Widodo, demanding Papuan independence, rejecting central government infrastructure building projects, and demanding the right for foreign journalists and aid workers to enter Papua.[40] In reprisals to obtain the massacred workers' bodies, the Indonesian military allegedly carried out airstrikes on at least four villages and used white phosphorus,[38] a chemical weapon banned by numerous countries and international organizations.[41] This was however denied by the Indonesian government.[42][43]

2019 Papuan protests

editFresh protests began on 19 August 2019 and mainly took place across Indonesian Papua in response to the arrests of 43 Papuan students in Surabaya, East Java for alleged disrespect of the Indonesian flag. Many of the protests involved thousands of participants, and some grew from local protests in Surabaya to demanding an independence referendum. In several locations, the protests turned into general riots, resulting in the destruction of government buildings in Wamena, Sorong and Jayapura. Clashes between protesters and counter-protesters and police resulted in injuries, with over 31 people killed from both the clashes and the rioting, mostly non-Papuan trapped when rioters burned houses.[44]

In response to the rioting, the government of Indonesia implemented an internet blackout in the region. A Reuters reporter from the Jakarta bureau described the unrest as "Papua's most serious in years".[45]

2020–present

editOn 25 April 2021, Special Forces major-general I Gusti Putu Danny Karya Nugraha, head of the Papua intelligence agency, was killed when he was shot in the head while in an ambush in a heavily-armed military convoy.[46]

On 5 March 2022, Sebby Sambom, a TPNPB-OPM spokesperson, alongside Terianus Satto supported the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, claiming alleged similarity of Ukrainian police and military treatment of the Russian minority as genocide with Indonesian police and military treatment of Papuans. TPNPB-OPM claimed Russian government support of pro-Russian separatists as justified, and claimed that both Indonesia and Ukraine are "capitalist puppets" of the United States.[1]

In 2023, Papuan separatists took a New Zealand pilot hostage, named Philip Mehrtens, and set fire to the plane. The flight was operated by Indonesian airline Susi Air that operates flights in and out of Papua.[47][48] The TPNPB has claimed responsibility for the kidnapping and attack, stating that they would be targeting all foreigners as a part of their campaign.[49] On the 15th of February, photos of the pilot showed him to be in relatively good health and guarded by armed insurgents from the Papua movement. The group said that he would not be freed from captivity until authorities recognise the independence of the region.[50]

On 3 April 2023, four Indonesian soldiers died and another five suffered gunshot injuries in an attack led by Egianus Kogoya in Nduga, Papua.[51][52]

Armed wing

editThe Free Papua Movement has many armed wings, namely:[53]

(Indonesian: Tentara Pembebasan Nasional Papua Barat; abbreviated TPNPB) (TPNPB-OPM) led by Goliath Tabuni.

(Indonesian: Tentara Papua Barat; abbreviated WPA) led by Damianus Magai Yogi.[54]

- West Papua Revolutionary Army

(Indonesian: Tentara Revolusi West Papua; abbreviated TRWP) led by Mathias Wenda.[53][55]

(Indonesian: Tentara Nasional Papua Barat; abbreviated TNPB) led by Fernando Worobay.

Organisational hierarchy and governing authority

editThe internal organisation of OPM is difficult to determine. In 1996 OPM's 'Supreme Commander' was Mathias Wenda.[56] An OPM spokesperson in Sydney, John Otto Ondawame, says it has nine more or less independent commands.[56] Australian freelance journalist Ben Bohane says it has seven independent commands.[56] Tentara Nasional Indonesia (TNI), Indonesia's army, says the OPM has two main wings, the 'Victoria Headquarters' and 'Defenders of Truth'. The former is small, and was led by M L Prawar until he was shot dead in 1991. The latter is much larger and operates all over West Papua.[56]

The larger organisation, or 'Defender of the Truth' or Pembela Kebenaran (henceforth PEMKA), was chaired by Jacob Prai, and Seth Roemkorem was the leader of Victoria Faction. During the killing of Prawar, Roemkorem was his commander.

Prior to this separation, TPN/OPM was one, under the leadership of Seth Roemkorem as the Commander of OPM, then the President of West Papua Provisional Government, while Jacob Prai as the Head of Senate. OPM reached its peak in organisation and management as it was structurally well organised. During this time, the Senegal Government recognised the presence of OPM and allowed OPM to open its embassy in Dakar, with Tanggahma as the ambassador.

Due to the rivalry, Roemkorem left his base and went to the Netherlands. During this time, Prai took over the leadership. John Otto Ondawame, who had left his law school in Jayapura because of being followed and threatened with death by the Indonesian ABRI day and night, became the right-hand man of Jacob Prai. It was Prai's initiative to establish OPM Regional Commanders. He appointed nine of them, most of whom were members of his own troops at the PEMKA headquarter, Skotiau, Vanimo-West Papua border.

Of those regional commanders, Mathias Wenda was the commander for region II (Jayapura – Wamena), Kelly Kwalik for Nemangkawi (Fakfak regency), Tadeus Yogi (Paniai Regency), and Bernardus Mawen for Maroke region. Tadeus Yogi died on 9 January 2009 suspected of poisoning,[57] Kelly Kwalik was shot and killed on 16 December 2009,[58] while Benard Mawen died in Kiunga hospital, PNG on 16 November 2018.[59]

The armed military wing of TPNPB in Nduga, Papua is headed by Egianus Kogoya.[51][52]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Dukung Rusia Serbu Ukraina, TPNPB-OPM Kecam Amerika dan Indonesia - Nasional". GATRAcom (in Indonesian). 5 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Libyan terrorism: the case against Gaddafi. - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com.

- ^ a b "Label Teroris untuk KKB Papua Akhirnya Jadi Nyata". Detik.com (in Indonesian). April 2021.

- ^ "Indonesia Classifies Papuan Rebels as Terrorist Group". Benar News.

- ^ a b Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (24 August 2015). "The current status of the Papuan pro-independence movement" (PDF). IPAC Report No.21. Jakarta, Indonesia. OCLC 974913162. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Lintner, Bertil (22 January 2009). "Papuans Try to Keep Cause Alive". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013.

- ^ "Report on Netherlands New Guinea for the year 1961". Wpik.org. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "Free Papua Movement (OPM)". Global Terrorism Database. University of Maryland, College Park. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Djopari, John R.G. (1993). Pemberontakan Organisasi Papua Merdeka (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gramedia Widiasarana Indonesia.

- ^ "Memorandum From Secretary of State Rusk to President Kennedy". History.state.gov. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "Memorandum From the Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs (Kohler) to Secretary of State Rusk". History.state.gov. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "Document 172 – Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XXIII, Southeast Asia – Historical Documents – Office of the Historian". History.state.gov. 24 April 1961. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Dept. of State Foreign Relations, 1961–63, Vol XXIII, Southeast Asia". Wpik.org. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "Charter of the United Nations, International Trusteeship System". Un.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "17th session of the General Assembly". Un.org. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Text of New York Agreement

- ^ "Protest and Punishment Political Prisoners in Papua Report by Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. 21 February 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "New York Times, Papuans at U.N. score Indonesia, Lobbyists asking nations to insure fair plebiscite" (PDF). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "National Security Archive at George Washington University, Document 8". Gwu.edu. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "New York Times interview July 5, 1969" (PDF). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Interview May 10, 1969" (PDF). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Indonesia, CNN (1 December 2021). "1 Desember, Sejarah Pengakuan Papua yang Dicap HUT OPM". nasional (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 April 2022.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Bishop, R. Doak; Crawford, James; William Michael Reisman (2005). Foreign Investment Disputes: Cases, Materials, and Commentary. Wolters Kluwer. pp. 609–611.

- ^ Chauvel, Richard (6 April 2011). "Filep Karma and the fight for Papua's future". Inside Story. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "Papua's struggle for independence". BBC News. 13 March 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Saragih, Bagus BT Saragih; Dharma Somba, Nethy (25 October 2011). "Police hunt for OPM rebels". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "Antara News article" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Berita article" (in Indonesian). August 2011.

- ^ "Suararpembaruan article" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Viva News article" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 11 April 2012.

- ^ westpapuamedia (9 April 2012). "Doubts grow of OPM responsibility for Puncak Jaya aircraft shooting". Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Dunigan, Molly and Petersohn, Ulrich (2015), The Markets for Force: Privatization of Security Across World Regions, University of Pennsylvania, ISBN 978-081224686-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oakes, Dan (7 December 2012). "Trained by a baron and backed by Bambi, now West Papua 'freedom fighter' faces jail". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Oakes, Dan (10 July 2013). "Granddad mercenary admits to arms training". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Wright, Stephen (25 September 2018). "Polish globe-trotter blunders into Indonesia-Papua conflict". Associated Press. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "Indonesia jails Polish tourist who met Papuan activists". Associated Press. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Tehusijarana, Karina M. (7 December 2018). "Papua massPapua mass killing: What happened". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Chemical weapons dropped on Papua". The Saturday Paper. 22 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ McBeth, John (5 December 2018). "Blood on the tracks of Widodo's Papuan highway". www.atimes.com. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "Istana Buka Suara Soal Dugaan Surat Terbuka OPM untuk Jokowi". nasional. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ "US intelligence classified white phosphorus as 'chemical weapon'". The Independent. 23 November 2005. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Indonesia denies use of chemical weapons in Papua". The Jakarta Post. 24 December 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "Indonesian military describes reports of chemical weapon attacks on West Papuans as 'fake news'". ABC News. 23 December 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Purba, John Roy (26 September 2019). "Daftar Nama 31 Korban Tewas Kerusuhan Wamena". KOMPAS.com. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Indonesia urges calm in Papua after two weeks of protests". Reuters. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "Indonesian intelligence official shot dead in Papua: Army". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Papua Separatists Burn Plane, Take N. Zealand Pilot Hostage". Jakarta Globe. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Teresia, Kate Lamb and Ananda (7 February 2023). "New Zealand pilot taken hostage in Indonesia, rebel group claims". The Age. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Rompies, Chris Barrett, Karuni (8 February 2023). "'Our new target is all foreigners': Papuan rebels' warning after taking Kiwi pilot hostage". The Age. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rebels in Indonesia's Papua say images show abducted NZ pilot in good health". Reuters. 15 February 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b Arkyasa, Mahinda (17 April 2023). "TNI Denies 9 Soldiers Killed by Armed Group in Nduga, Papua". Tempo. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ a b SAPTOWALYONO, DIAN DEWI PURNAMASARI (18 April 2023). "Five TNI Soldiers still Sought for After a Shooting Contact in Nduga". kompas.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ a b "KKB Papua Punya Tiga Sayap Militer, Damianus Magai Yogi Klaim Sebagai Panglima Tertinggi". POS-KUPANG.com. 5 January 2023.

- ^ Rohmat, Rohmat (11 September 2022). "Ngamuk Atas Klaim Komnas HAM Temui Panglima OPM, TPNPB: Mereka Menjaring Angin". GATRAcom (in Indonesian). Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Strangio, Sebastian. "In Papua Fighting, Indonesian Forces Claim Rebel Commander Killed". The Diplomat. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d van Klinken, Gerry (1996). "OPM information". Inside Indonesia. 02. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007.

- ^ "'A safe and peaceful life is impossible for us': Story of children of Papua independence fighters (Part 1/2)". West Papua Daily. 31 January 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Indonesia police 'kill' Papua separatist Kelly Kwalik BBC News, 16 December 2009

- ^ "Bergerilya 50 Tahun Jenderal Benard Mawen Tutup Usia". Suara Papua. 17 November 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

Further reading

edit- Bell, Ian; Feith, Herb; Hatley, Ron (May 1986). "The West Papuan Challenge to Indonesian Authority in Irian Jaya: Old Problems, New Possibilities" (PDF). Asian Survey. 26 (5): 539–556. doi:10.2307/2644481. JSTOR 2644481.

- Bertrand, Jacques (May 1997). ""Business as Usual" in Suharto's Indonesia". Asian Survey. 3 (5): 441–452. doi:10.2307/2645520. JSTOR 2645520.

- Evans, Julian (24 August 1996). "Last stand of Stone Age man". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Monbiot, George (2003) [1989]. Poisoned Arrows: An Investigative Journey to the Forbidden Territories of West Papua (2nd ed.). Devon, England: Green Books. ISBN 9781903998274.

- Osborne, Robin (1985). Indonesia's Secret War: The Guerilla Struggle in Irian Jaya. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9780868615196.

- van der Kroef, Justus M (August 1968). "West New Guinea: The Uncertain Future". Asian Survey. 8 (8): 691–707. doi:10.2307/2642586. JSTOR 2642586.