An oenochoe, also spelled oinochoe (Ancient Greek: οἰνοχόη; from Ancient Greek: οἶνος, oînos, "wine", and Ancient Greek: χέω, khéō, lit. 'I pour', sense "wine pourer"; pl.: oinochoai; Neo-Latin: oenochoë, pl.: oenochoae; English pl.: oenochoes or oinochoes), is a wine jug and a key form of ancient Greek pottery.

| Oenochoe | |

|---|---|

| οἰνοχόη | |

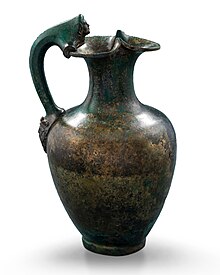

Terracotta trefoil oenochoe, Wild Goat style, c. 625 BC – 600 BC, in the Louvre. Below: bronze trefoil-mouthed oenochoe with Dionysus head on handle attachment, 330–320 BC, part of the Vassil Bojkov collection, Sofia, Bulgaria. | |

| |

| Material | Mainly terracotta, rarely metals, stone, and later glass |

| Size | Typically 25 centimetres (9.8 in) or less in height |

| Writing | None in the Bronze Age, illustration names of depicted scenes in classical times |

| Classification | Oenochoe, "wine pourer" |

| Culture | Cross-cultural in Mediterranean civilizations |

Intermediate between a pithos (large storage vessel) or amphora (transport vessel), and individual cups or bowls, it held fluid for several persons temporarily until it could be poured. The term oinos (Linear B: "wo-no") appears in Mycenaean Greek, but not the compound. The characteristic form was popular throughout the Bronze Age, especially at prehistoric Troy. In classical times for the most part the term oinochoe implied the distribution of wine. As the word began to diversify in meaning, the shape became a more important identifier than the word. The oinochoe could pour any fluid, not just wine. The English word, pitcher, is perhaps the closest in function.

Beazley's ten types

editThere are many different forms of oenochoae; Sir John Beazley distinguished ten types. The earliest is the olpe (ὀλπή, olpḗ), with no distinct shoulder and usually a handle rising above the lip. The "type 8 oenochoe" is what one would call a mug, with no single pouring point and a slightly curved profile. The chous (χοῦς; pl.: choes) was a squat rounded form, with trefoil mouth. Small examples with scenes of children, as in the example illustrated, were placed in the graves of children.[1]

Characteristics of oenochoae

editOenochoae may be decorated or undecorated.[2] They typically have only one handle, which may be opposite a trefoil mouth and pouring spout. At its most distinct development, the trefoil mouth offers three alternative directions of pouring, one opposite the handle, and two to the side, an advantage at a crowded table not afforded by English pitchers. Their size also varies considerably; most, at up to 25 centimetres (9.8 in) tall, could be comfortably held and poured with one hand, but there are much larger examples.

Most Greek oenochoae were in terracotta, but oenochoae of precious metals were not unknown, presumably among elements of society that could afford them, though but few have survived.[3] Large versions in stone were sometimes used as grave markers, often carved with reliefs. In pottery, some oinochoai are "plastic", with the body formed as sculpture, usually one or more human heads.

Prehistoric oenochoae were at first hand-made, unpolished, and undecorated. Low-economy oenochoae remained so, but gradually incised bands with simple motifs such as zig-zags and spirals, or burnished, monochrome surfaces, became common. In the Late Bronze Age the incised bands were painted for a more striking surface, and from then on the Greek oinochoai followed the traditional course of development for Greek decoration. Among the higher-quality pots, quite a few masterpieces have survived.

Gallery of oenochoae

edit-

Oinochoe Shape 1, H. 22 cm (8+1⁄2 in), diam. 13.5 cm (5+1⁄4 in), Eos (Dawn) pursuing Tithonus. Attic red-figure, 470–460 BC.

-

Oinochoe Shape 2, H. 23.5 cm (9+1⁄4 in), diam. 14.3 cm (5+1⁄2 in), Attic, 4th century

-

Oinochoe Shape 3, H. 10.5 cm (4.1 in), diam. 8.1 cm (3.2 in)

-

Oinochoe Shape 7, H. 21 cm (8+1⁄4 in), diam. 12.8 cm (5.0 in), Javelin thrower. Attic red-figured, c. 450 BC.

-

Oinochoe Shape 8, 8th century BC

-

Oinochoe Chous, last decade of the 5th century BC, 9.1 cm × 7 cm (3.6 in × 2.8 in). Probably used in a child's grave.

-

Plastic version with woman's head

-

Funerary oinochoe, with "farewell" scene with a deceased woman, third quarter of the 4th century BC

-

Bronze oenochoe, Nova Zagora, Bulgaria, with a trefoil spout

-

Archaic period, 750–600 BC

-

Oinochoe by the Shuvalov Painter (Berlin F2414) with famous erotic scene

-

The Dipylon inscription, c. 740 BC, perhaps the earliest datable Greek writing

-

Squat oinochoe, with ibex and lions, Otterlo Painter, late 7th c. BC

-

Apulian red-figure oinochoe by the White Saccos Workshop

-

Dispute between Ajax and Odysseus for Achilles' armour. Attic black-figure oinochoe, c. 520 BC. Kalos inscription. H. 20 cm (7+3⁄4 in), diam. 13.7 cm (5+1⁄2 in).

-

Iberian oinochoe with vegetal decoration, Cartagena, Spain

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Beazley Archive Archived 2017-04-23 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University, "Oinochoe, olpe and chous"

- ^ Woodford, S. (1986). An Introduction to Greek Art. London: Duckworth, p. 12. ISBN 0-7156-2095-9

- ^ Silver 'oinochoe' from the "Tomb of Philip" at Vergina, accessdate=2015-06-24

External links

edit- Media related to Oinochoes at Wikimedia Commons