Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (Italian: Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise) is an Italian national park established in 1923. The majority of the park is located in the Abruzzo region, with smaller parts in Lazio and Molise. It is sometimes called by its former name Abruzzo National Park. The park headquarters are in Pescasseroli in the Province of L'Aquila. The park's area is 496.80 km2 (191.82 sq mi).[1]

| Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park | |

|---|---|

| Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise | |

| |

| |

| Location | Abruzzo, Lazio, Molise |

| Nearest city | Rome |

| Area | 496.80 km2 (191.82 sq mi) |

| Established | 1923 |

| Governing body | Ministero dell'Ambiente |

| www | |

It is the oldest park in the Apennine Mountains, and the second oldest in Italy, with an important role in the preservation of species such as the Italian wolf, Abruzzo chamois and Marsican brown bear. Other characteristic fauna of the park are red deer and roe deer, wild boar and the white-backed woodpecker. The protected area is around two thirds beech forest, though many other tree species grow in the area, including silver birch and black and mountain pines.

History

editThe idea for the Abruzzo National Park arose in the years following World War I thanks to the work of Erminio Sipari, environmentalist, member of Italian Parliament and cousin of Benedetto Croce.[2] Between the months of October and November 1921, the municipality of Opi leased 5 square kilometres of land to a private federation with the aim of protecting flora and fauna and Sipari founded in Rome an organization to administer the reserve.[3] So the Park was founded in September 1922.[4] Over the next few years the territory of the park expanded into neighbouring municipalities until it covered around 120 km2 by 1923, when protection was enshrined in law. A period of intense activity followed and the park had further expanded to around 300 km2 when it was abolished by the Fascist government in 1933.

Re-establishment of the park in 1950 coincided with a period of financial difficulty, followed by a building boom which saw more than 12,000 trees felled for the construction of houses, roads and ski tracks. A reorganization of the park management at the end of the 1960s heralded better times and by 1976, further expansion to 400 km2, followed at the request of villages in neighbouring Molise, that were convinced by the economic benefits of the park. Today, at 500 km2, the area of the park is 100 times larger than the original reserve. However, the park's role in the marsican bear conservation program is now strongly debated; while every year there are monitoring actions of the total bear's population there have been recently some problems related to the pave actions carried out inside the park's boundaries and the building projects to connect the only ski track of the park to the opposite valley, which is a delicate spot for the bear's movements.

Geography

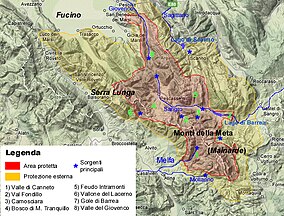

editThe mountains within the park are Petroso (2,249 metres), Marsicano (2,245 metres), Meta (2,242 metres), Tartaro (2,191 metres), Jamiccio (2,074 metres), Cavallo (2,039 metres), Palombo (2,013 metres).[5] These are included in the Monti della Meta. The Sangro River rises near Pescasseroli and runs south-east through the artificial Lago di Barrea before leaving the park and turning to the north-east. Other rivers in the park are the Giovenco, Malfa and Volturno. Other lakes are Vivo, Pantaniello, Scanno, Montagna Spaccata, Castel San Vincenzo, Grottacampanaro, and Selva di Cardito.

Fauna

editIn wildlife terms, the main attractions of the park are the Marsican brown bear and Italian wolf. While official figures report 50-70 bears in this genetically isolated population, the declining population is actually estimated at closer to 30.[6] The shift from local agriculture to development in Abruzzo (including a controversial proposed ski resort) and poaching, threaten this remaining small population.[7] While Wolves were once rarer (as low as 40), numbers have reportedly rebounded in recent years.[8]

The presence of the Eurasian lynx in the park is still controversial, and there are no scientific studies that prove it; however, there are some unconfirmed sightings.[citation needed]

In greater numbers, in the thicker areas of the forest, are red deer and roe deer, reintroduced in the seventies, and the wild boar. Other reclusive inhabitants of the forest include European polecat, Eurasian badger, Eurasian otter and two species of marten; pine marten and beech marten. Higher, above the forest, Abruzzo chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica ornata) live alone or in small groups.[citation needed]

Animals that are easier to see include red fox, the European hare, the least weasel, the European mole, and the western European hedgehog. Dormice and red squirrel s are also quite frequently seen. Other mammals recorded in the park are the snow vole, the edible dormouse, the European wildcat and the Garden dormouse.[citation needed]

Birds

editMany birds of prey inhabit the park. Most notable amongst them is the golden eagle, represented by six breeding couples, which, despite living in the more inaccessible regions, can often be seen soaring over central areas of the park in search of prey such as small mammals or even sick, young chamois. Other raptors that reside within the park include goshawks, peregrine falcons, Eurasian buzzards, Eurasian kestrels and Eurasian sparrowhawks. Less visible, but perhaps more audible, to the nighttime visitor are several species of owl, the little owl, the barn owl and the tawny owl. Woodland birds include the European green woodpecker and the rare white-backed woodpecker, cliffs harbor the red-billed chough and alpine chough and bare mountain birds include the rock partridge and white-winged snowfinch. Streams provide habitat for the grey wagtail and white-throated dipper.

Plants

editThe flora of the park is rich and interesting. A comprehensive list of plants would extend to more than 2,000 species without including lichens, algae or fungi. Flowers present in the area include Marsican Iris (Iris marsica),[9] gentian, primrose, cyclamen, violets and the lily. The most well-known flower of the park is the rare lady's slipper (Cypripedium calceolus), a yellow and black orchid.

The predominant tree of the park is the beech which covers 60% of the area, generally grows at 900–1800 m altitude and provides a stunning display of color throughout the whole year. Notable also the presence of some old-growth beech forests in the northern part of the park. Other trees are the black pine, the mountain pine and the silver birch.

Municipalities

editThe park covers 25 municipalities, distributed across 3 provinces.[5]

Province of L'Aquila:

- Alfedena, Barrea, Bisegna, Civitella Alfedena, Gioia dei Marsi, Lecce nei Marsi, Opi, Ortona dei Marsi, Pescasseroli, Scanno, Villavallelonga, Villetta Barrea

Province of Frosinone:

- Alvito, Campoli Appennino, Pescosolido, Picinisco, San Biagio Saracinisco, San Donato Val di Comino, Settefrati, Vallerotonda

Provincia of Isernia:

Activities

editMany outdoor activities are possible within the park including,

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise". parks.it. 2004–2010..

- ^ Luigi Piccioni, Erminio Sipari. Origini sociali e opere dell'artefice del Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo, University of Camerino 1997; James Sievert, The Origins of Nature Conservation in Italy, Peter Lang (publishing company), Bern 2000, pp. 165-181; Marco Armiero - Marcus Hall (ed.), Nature and History in Modern Italy, Ohio University 2010

- ^ "Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise". parcoabruzzo.it. 2011.

- ^ Lorenzo Arnone Sipari, Il Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo liberato dall'allagamento. Un conflitto tra tutela ambientale e sviluppo indutriale durante il fascismo, "Rivista della Scuola Superiore dell'Economia e Finanza", 2003, nr. 8-9: 27-39 Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine; Lorenzo Arnone Sipari (ed.), Scritti scelti di Erminio Sipari sul Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo (1922-1933), Trento 2011.

- ^ a b "The National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise". NAP - Network of Adriatic Parks. Archived from the original on 2009-04-10.

- ^ Paynton, Brian (2006). In Bear Country. Old Street Publishing, London. ISBN 978-1-905847-14-3.[page needed]

- ^ Hooper, John (21 August 2004). "Italy battles to save the last of its wild bears". The Guardian.

- ^ "Wolves at Florence's gates". Italy Magazine. 13 June 2007.

- ^ "The Abruzzo National Park". opionline.it. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

External links

edit- "Official website" (in Italian).

- "Italy - Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park". Wild Zone.[permanent dead link]

- Fletcher, Adrian (2000–2010). "Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo". paradoxplace.com. Archived from the original on 2010-04-14.