The March trilogy is an autobiographical black and white graphic novel trilogy about the civil rights movement, told through the perspective of civil rights leader and U.S. Congressman John Lewis. The series is written by Lewis and Andrew Aydin, and illustrated and lettered by Nate Powell. The first volume, March: Book One, was published in August 2013, by Top Shelf Productions.[1] and the second volume, March: Book Two, was published in January 2015, with both volumes receiving positive reviews. March: Book Three was published in August 2016 along with a slipcase edition of the March trilogy.

| March: Book One | |

|---|---|

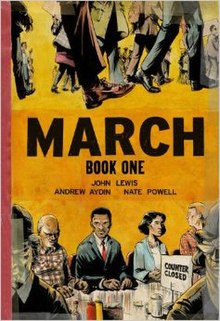

Cover to March: Book One. Art by Nate Powell | |

| Creator | John Lewis Andrew Aydin Nate Powell |

| Page count | 121 pages |

| Publisher | Top Shelf Productions |

| Original publication | |

| Date of publication | August 13, 2013 |

| ISBN | 978-1603093002 |

| March: Book Two | |

|---|---|

| Creator | John Lewis Andrew Aydin Nate Powell |

| Page count | 192 pages |

| Publisher | Top Shelf Productions |

| Original publication | |

| Date of publication | January 20, 2015 |

| ISBN | 978-1603094009 |

| March: Book Three | |

|---|---|

| Creator | John Lewis Andrew Aydin Nate Powell |

| Page count | 256 pages |

| Publisher | Top Shelf Productions |

| Original publication | |

| Date of publication | August 2, 2016 |

| ISBN | 978-1603094023 |

Publication history

editMartin Luther King and the Montgomery Story

editWhen John Lewis was 15 years old and living in rural Alabama, 50 miles south of Montgomery, he first heard of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Montgomery bus boycott through James Lawson, who was working for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (F.O.R.). Lawson introduced Lewis to Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a 10-cent comic book published by F.O.R. that had a profound impact on Lewis. The comic book demonstrated in clear fashion to Lewis the power of the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence. Lawson became a mentor to Lewis, and Lewis began attending meetings every Tuesday night with approximately 20 other students from Fisk University, Tennessee State University, Vanderbilt University, and American Baptist College to discuss nonviolent protest, with The Montgomery Story serving as one of their guides. The Montgomery Story would also influence other civil rights activists, including the Greensboro Four.[2]

Congressman Lewis and Andrew Aydin

editLewis became a U.S. congressman for Georgia's 5th congressional district in 1987.[3][4] While working on his 2008 reelection campaign, Lewis told his telecommunications and technology policy aide, Andrew Aydin, about The Montgomery Story and its influence.[2]

Aydin, who had been reading comics since his grandmother bought him a copy of Uncanny X-Men #317 off a Piggly Wiggly spinner rack when he was eight years old,[5] found a digital copy of the book on the Internet and spent years tracking down an original print copy on eBay. Aydin explains The Montgomery Story's influence on March thus:

Once he told me about it, and I connected those dots that a comic book had a meaningful impact on the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, and in particular on young people, it just seemed self-evident. If it had happened before, why couldn't it happen again? I think part of that impulse was born out of a frustration with the way things are in our politics and our culture. The election of Barack Obama seemed like it was opening a huge door, and I think perhaps we put all of our dreams and aspirations on him, and failed to recognize that we too have to rise up, and we too have to make our voices heard. He's one man and can't do it alone, and we did not make Congress, we did not make our state legislators do what we needed them to do to make the society we all imagined in that campaign. And when I look back on it, the Civil Rights Movement was so successful at using non-violence in so many different ways: Birmingham, Montgomery, Selma in particular, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the Freedom Rides, the March on Washington, all held different aspects, and when you look back at the comic book it was one tactic. It was the way they did it in Montgomery. But what if we took the broader story and showed all of the different tactics. Because what worked in Birmingham and what worked in Montgomery didn't necessarily work in Albany, and there were different reasons. The Sheriffs started adapting. They were moving prisoners out of city jails and putting them in county jails, and things like that, so you couldn't fill them up as fast. And we need to adapt. The tactics, the principles, they still work, but we need to adapt our use of them. And so showing how others had done that and how it had progressed seemed like such a natural way to sort of pursue those ends.[2]

Aydin repeatedly suggested that Lewis himself write a comic book. (Lewis had previously written a traditional autobiography, Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, co-authored with journalist Michael D'Orso and published in 1998. A national bestseller, that book won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, was selected as a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, was included on Newsweek magazine's list of "50 Books For Our Times," and was named Nonfiction Book of the Year by the American Library Association.) Eventually Lewis decided to commit to Aydin's project, on the condition that Aydin write it with him. Aydin, who was in the middle of writing his master's thesis on The Montgomery Story and how it helped inspire protest movements around the world, agreed to the project, which he calls a life-changing moment. Much of Aydin's work on the project was listening to Lewis dictate his life story, anecdotes of which Aydin had often heard Lewis relate to children, parents and others visiting his office, and transcribing it.[5]

Illustrator Nate Powell

editIn the early 2010s, illustrator Nate Powell learned that Top Shelf would be publishing March, which Lewis and Aydin had finished writing. A few weeks later, Powell was contacted by Top Shelf co-founder Chris Staros, who suggested he try out for the assignment. Although he already had other projects lined up, Powell sent some demo pages to Lewis and Aydin, and over the course of their subsequent correspondence, they realized that Powell would be well-suited for the job. Although Powell had illustrated stories that were "true to life", such as the 2012 graphic Silence of our Friends, this would be the first time he would depict real-life historical figures, 300 of which Powell estimates are rendered in total in the trilogy. The scene in which Lewis meets Martin Luther King Jr. for the first time was the first page Powell drew for March, and although he found approaching that page difficult, he stated it made subsequent depictions of real-life people easier. Powell's approach was to develop a visual shorthand for each real person he had to draw, in the form of a "master drawing" to act as a reference template for that person's features, one that emphasized the person's skull structure, in lieu of referring constantly to photo reference in the course of the project, so that the characters would not look "too stale or photo-derived". He employed lifestyle and illustration books from the 1950s and 1960s, as well as Google searches, to depict fashion and automobiles of given time periods accurately.[5]

The creative team eventually realized that the story required 500–600 pages, and that it should be broken up into volumes. This allowed Powell to give certain sequences the length he needed to render them at a pace he felt they required, in particular scenes of anxiety or tension. The scene in which Lewis wakes up and prepares to attend the Obama inauguration, for example, was expanded from two pages to five. Other examples were the scenes in which the child John Lewis hid under his house to avoid doing his farm chores or attend school, and the scene in which Lewis took a trip to Alabama through the segregated South with his uncle, which was expanded from two pages to six.[5]

Releases

editThe first book in the trilogy, March: Book One, was released in August 2013. The second book, March: Book Two, was released January 20, 2015. The third book, March: Book Three was released August 2, 2016.[6][7] All of these books are available in paperback as well as e-book formats.

Plot

editBook One

editOn March 7, 1965, John Lewis, a young man, stands on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama with fellow civil rights activists during the Selma to Montgomery marches on "Bloody Sunday". They are confronted by Alabama state troopers, who order the protestors to turn around. When the protestors refuse, the troopers attack them, beating them and dousing them with tear gas.

The scene cuts to the book's framing sequence, set on January 20, 2009, with Lewis, now a U.S. congressman for Georgia's 5th congressional district, waking up and preparing for the first inauguration of Barack Obama.[5] He is greeted at his office by a woman from Atlanta and her two young sons, who want to learn about their history.

Lewis begins telling the family his life story, beginning as a young boy taking care of his parents' chickens on the 110 acres of cotton, corn and peanut fields in Pike County, Alabama that his father bought for $300 cash in 1940. Though Lewis was fond of his chickens and took pride in their care, he really wanted to be a preacher when he grew up, having been inspired by the Bible that an uncle of his gave him for Christmas when he was four years old. By the time he was five, he could read it by himself, having been particularly captivated by the passage in John 1:29 "Behold the lamb of God, which taketh away the sins of the world." As Lewis grew older, he began spending more time doing schoolwork, studying and learning more about what was happening in the world around him, which would later lead to his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement.

Although his parents had raised him to stay out of trouble, other members of his family encourage his interests in civil rights, such as his maternal uncle Otis Carter, a teacher and school principal who had long noted something special in Lewis. Carter took Lewis on Lewis' first trip north in June 1951, driving through the segregated South to Buffalo, New York, whose busy and unsegregated urban life was an "otherworldly experience" for young Lewis. Though happy when he returned home, home never felt the same to him. When he started school again months later, he began riding the bus to school, whose segregated nature was another reminder of how different the lives of Lewis and his siblings were from those of white children. Though Lewis enjoyed school, it was sometimes a luxury his family could not afford during planting and harvesting season, when they kept him at home to work on the farm. Lewis responded by sneaking off to school, despite scoldings by his father. In May 1954, near the end of Lewis' freshman year in high school, when the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case ruled public school segregation unconstitutional, Lewis thought it would improve his schooling, but his parents continued to advise him to not cause trouble. He also noticed that the injustices against blacks were not mentioned by local church ministers and that his minister drove a very nice automobile. One Sunday morning in early 1955, Lewis was listening to the radio station WRMA Montgomery, when he heard a sermon by Martin Luther King Jr. Profoundly inspired by King's social gospel and other aspects of the Civil Rights Movement, Lewis, five days before his sixteenth birthday, preached his first public sermon. This event was publicized in the Montgomery Advertiser, marking the first time Lewis saw his name in print. Lewis subsequently attended American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville while washing dishes to make money. Wanting to do more for the movement, he repeatedly applied as a transfer student to Troy University, where no black student was allowed, only to be rejected. Lewis wrote to civil rights leaders Ralph Abernathy and Fred Gray, who arranged a meeting between Lewis and King. King explained that to attend Troy, they would have to sue the state of Alabama and the Board of Education and that because Lewis was not old enough to file a suit, he would have to get his parents' permission. Fearful for both their lives and those of their loved ones, Lewis' parents refused.

By March 1958, Lewis was attending First Baptist Church in Nashville, and participated in workshops on nonviolence organized by Vanderbilt University Divinity School student James Lawson, who represented the Fellowship of Reconciliation (F.O.R.), a pacifist group committed to nonviolence. F.O.R. published a comic book, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, that explained how to implement passive resistance as a tool for desegregation. As the group prepared to conduct a sit-in at a department store lunch counter, the Greensboro Four, inspired by The Montgomery Story, conducted one of their own in Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1, 1960. On February 7, the Nashville group conducted theirs, occupying a lunch counter at a local Woolworth store, refusing to cease amid verbal abuse by whites and the closing of the counter by the establishment. The group repeated this at other stores and remained steadfast even when whites began inflicting physical violence upon them. The group was eventually arrested on February 27, 1960, the first of many for Lewis, but the lunch counters continued to fill with activists, as did the jails. Declining the jail's reduction of their bail from $100 to $5 each, the police eventually released Lewis' group later that night.

The activists were later convicted of disturbing the peace, and when they refused to pay the fines levied against them, they were given prison sentences, outraging the country and inspiring more sit-ins. Nashville Mayor Ben West ordered their release on March 3 and formed a biracial committee to study segregation in the city, asking the group to temporarily halt the sit-ins while the committee worked, to which Lewis' group agreed. When Vanderbilt University threatened to fire Lawson, dozens of faculty and staff threatened to resign in protest, making national headlines. On March 25, the group, numbering over 100, marched to nine downtown stores. Within local churches, the black community organized a boycott of all downtown stores, and the group resumed the sit-ins, rejecting the committee's suggestion for a "partial integration", which they viewed as indistinguishable from partial segregation. On April 19, dynamite was thrown at the house of Alexander Looby, an acquaintance and lawyer of the activists, and in response, thousands of protestors gathered at Tennessee State University to march on City Hall. Confronted by activist Diane Nash, Mayor West stated that he would do all he could to enforce the law without prejudice, and appealed to citizens to end discrimination, but could not force store owners to serve those they did not wish to. The next evening, Dr. King arrived to speak, and on May 10, six downtown stores served food to black customers for the first time in the city's history.

Book Two

editBook Two begins in 1961 when the Freedom Riders began riding interstate buses inside the Deep South. Racial tensions contributed to the Birmingham Church Bombing in September 1963. The bombing marked a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement and contributed to support for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Book Three

editBook Three follows at the end of 1963 when the Civil Rights Movement had the full attention of the country, and as a chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis is helping to guide the movement. SNCC continues to force the nation to confront its injustice and racism but the danger grows with more Jim Crow laws with the threats of violence and death. Lewis and an army of activists launched a series of campaigns, including the 1963 Freedom Ballot and Mississippi Freedom Summer. The movement to give voting rights to all people that resulted in various Selma to Montgomery marches came to a historic showdown with Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama.

Reception

editThe trilogy holds a critics' rating of 9.6 out of 10 at the review-aggregation website Comic Book Roundup, based on 10 reviews.[8]

Book One

editMarch: Book One holds an average 9.4 out of 10 rating at the review aggregator website Comic Book Roundup, based on five reviews.[9]

Jim Johnson of Comic Book Resources gave the book four and a half out of five stars, calling it "an excellent and fascinating historical account" of Lewis' life and "an absolutely wonderful story about one man who played a very important role in one of this country's most important social revolutions, and continues to play an important part to this very day". Johnson further commented, "Powell's washed-out greytones combine with Congressman Lewis and Aydin's captivating words and story to give the entire account the feel of a compelling, period documentary."[10]

Noah Sharma of Weekly Comic Book Review gave March Book One a grade of A−, calling it "an artful and important graphic novel". Sharma praised Lewis as a talented storyteller, called the dialogue "sharp and cleverly delivered" and remarked that Powell "fills his panels with depth and vibrancy". Sharma concluded, "The narrative tools employed by March are simple ones, but they form together to create something moving and complex. Aydin and Powell know when to let their art support the congressman and when to let his experience speak for itself."[11]

March: Book One received an "Author Honor" from the American Library Association's 2014 Coretta Scott King Book Awards.[12] Book One also became the first graphic novel to win a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, receiving a "Special Recognition" bust in 2014.[13]

March: Book One was selected by first-year reading programs in 2014 at Michigan State University,[14] Georgia State University,[15] and Marquette University.[16]

Book Two

editMarch Book Two was ranked #2 on The Village Voice's 2014 list "The 10 Most Subversive Comics at New York Comic Con".[17]

March: Book Two was awarded the Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work in 2016.[18]

Book Three

editMarch: Book Three debuted at #1 on the New York Times bestseller list for graphic books and brought the whole trilogy into the top three spots, which they held for six continuous weeks.

On November 16, 2016, March: Book Three won the National Book Award for Young People's Literature. It was the first graphic novel to ever receive a National Book Award. March: Book Three was awarded the Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work in 2017.[19]

On January 23, 2017, March: Book Three won the Coretta Scott King (Author) Book Award, the Michael L. Printz Award for excellence in literature written for young adults, the Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award, and the YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adults.[20]

Sequel

editIn 2018, Lewis and Andrew Aydin co-wrote a sequel to the March series entitled Run, which documents Lewis's life after the passage of the Civil Rights Act,[21] including his leadership of The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), conflict with the Ku Klux Klan, disputes over SNCC tactics, the Vietnam War, and the rise of the Black Power movement. Lewis said of the book, "In sharing my story, it is my hope that a new generation will be inspired by Run to actively participate in the democratic process and help build a more perfect union here in America."[22] L. Fury illustrated the book,[23] while Nate Powell, who illustrated March, also contributed to the art.[24] The book was originally scheduled to be released in August 2018, but encountered delays,[21] and was eventually released on August 3, 2021, a year after Lewis' death, one of his last endeavours before he died.[25]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Cavna, Michael (August 12, 2013). "In the graphic novel 'March,' Rep. John Lewis renders a powerful civil rights memoir". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Joseph (September 16, 2013). "Congressman John Lewis And Andrew Aydin Talk Inspiring The ‘Children Of The Movement’ With ‘March’ (Interview)" Archived 2013-09-18 at the Wayback Machine. ComicsAlliance.

- ^ "GA District 5 – D Primary Race – Aug 12, 1986". Our Campaigns. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ "GA District 5 Race – Nov 04, 1986". Our Campaigns. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Herbowy, Greg (Fall 2014). "Q+A: Congressman John Lewis, Andrew Aydin & Nate Powell". Visual Arts Journal. School of Visual Arts (November 17, 2016). pp. 48–51.

- ^ Cavna, Michael (7 March 2016). "Exclusive: Rep. John Lewis on unity, Trump and his new graphic memoir, 'March: Book Three'" – via washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Lewis, John; Aydin, Andrew (2 August 2016). March: Book Three. Top Shelf Productions. ISBN 978-1603094023.

- ^ "March". Comic Book Roundup. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "March: Book One #1 Reviews" Archived 2014-10-27 at the Wayback Machine. Comic Book Roundup. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Jim (August 14, 2013). "March: Book One". Comic Book Resources.

- ^ Sharma, Noah (August 20, 2013). "March (Book One) – Review". Weekly Comic Book Review.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King Book Awards – All Recipients, 1970–Present". American Library Association. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (May 21, 2014). "March Book One is first graphic novel to win the RFK Book Award". Comics Beat.

- ^ "About the Book" Archived 2015-01-12 at the Wayback Machine. City of East Lansing & Michigan State University. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ "Fall 2014 Selection" Archived 2014-12-20 at the Wayback Machine. Georgia State University. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ "About the book". Marquette University, Office of Student Development. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Staeger, Rob (October 10, 2014). "The 10 Most Subversive Comics at New York Comic Con" Archived 2014-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. The Village Voice.

- ^ Brown, Luke (July 23, 2016). "Brilliant Art, Tremendous Stories and Daring Creators: The 2016 Eisner Award Winners [SDCC 2016]". ComicsAlliance.

- ^ Lovett, Jamie (November 9, 2017). "Here Are Your 2017 Eisner Awards Winners". ComicBook.com.

- ^ JCARMICHAEL (2017-01-23). "American Library Association announces 2017 youth media award winners". News and Press Center. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ^ a b Arrant, Chris (July 26, 2018). "REP. JOHN LEWIS' RUN Pulled From Schedule". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020.

- ^ Reid, Calvin (February 16, 2018). "Abrams to Publish Sequel to John Lewis' March Trilogy". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Reid, Calvin. "Rep. John Lewis's Life Story Continues in 'Run: Book One'". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Rappaport, Michael (April 11, 2018). "'Run' Follows Award-Winning Graphic Novel 'March' in Civil-Rights Chronicle". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Cavna, Michael (August 2, 2021). "John Lewis finished this graphic memoir as he died. He wanted to leave a civil rights 'road map' for generations to come". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

External links

edit- March. C-SPAN. November 21, 2015

- March at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)