Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s, slowed during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and continued until 1981. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states.[3] In 1891, the largest single mass lynching in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.[4][5]

Lynchings followed African Americans with the Great Migration (c. 1916–1970) out of the American South, and were often perpetrated to enforce white supremacy and intimidate ethnic minorities along with other acts of racial terrorism.[6] A significant number of lynching victims were accused of murder or attempted murder. Rape, attempted rape, or other forms of sexual assault were the second most common accusation; these accusations were often used as a pretext for lynching African Americans who were accused of violating Jim Crow era etiquette or engaged in economic competition with Whites. One study found that there were "4,467 total victims of lynching from 1883 to 1941. Of these victims, 4,027 were men, 99 were women, and 341 were of unidentified gender (although likely male); 3,265 were Black, 1,082 were white, 71 were Mexican or of Mexican descent, 38 were American Indian, 10 were Chinese, and 1 was Japanese."[7]

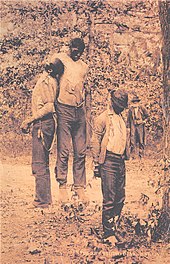

A common perception of lynchings in the U.S. is that they were only hangings, due to the public visibility of the location, which made it easier for photographers to photograph the victims. Some lynchings were professionally photographed and then the photos were sold as postcards, which became popular souvenirs in parts of the United States. Lynching victims were also killed in a variety of other ways: being shot, burned alive, thrown off a bridge, dragged behind a car, etc. Occasionally, the body parts of the victims were removed and sold as souvenirs. Lynchings were not always fatal; "mock" lynchings, which involved putting a rope around the neck of someone who was suspected of concealing information, was sometimes used to compel people to make "confessions". Lynch mobs varied in size from just a few to thousands.

Lynching steadily increased after the Civil War, peaking in 1892. Lynchings remained common into the early 1900s, accelerating with the emergence of the Second Ku Klux Klan. Lynchings declined considerably by the time of the Great Depression. The 1955 lynching of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy, galvanized the civil rights movement and marked the last classical lynching (as recorded by the Tuskegee Institute). The overwhelming majority of lynching perpetrators never faced justice. White supremacy and all-white juries ensured that perpetrators, even if tried, would not be convicted. Campaigns against lynching gained momentum in the early 20th century, championed by groups such as the NAACP. Some 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress between the end of the Civil War and the Civil Rights movement, but none passed. Finally, in 2022, 67 years after Emmett Till's killing and the end of the lynching era, the United States Congress passed anti-lynching legislation in the form of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act.

Background

editCollective violence was a familiar aspect of the early American legal landscape, with group violence in colonial America being usually nonlethal in intention and result. In the 17th century, in the context of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the British Isles and unsettled social and political conditions in the American colonies, lynchings became a frequent form of "mob justice" when the authorities were perceived as untrustworthy.[8] In the United States, during the decades after the Civil War, African Americans were the main victims of racial lynching, but in the American Southwest, Mexican Americans were also the targets of lynching as well.[9]

At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh (who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail) was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of over 1,000 people.[10]

According to historian Michael J. Pfeifer, the prevalence of lynchings in post–Civil War America reflected people's lack of confidence in the "due process" of the U.S. judicial system. He links the decline in lynchings in the early 20th century to "the advent of the modern death penalty", and argues that "legislators renovated the death penalty...out of direct concern for the alternative of mob violence". Between 1901 and 1964, Georgia hanged and electrocuted 609 people. Eighty-two percent of those executed were Black men, even though Georgia was majority white. Pfeifer also cited "the modern, racialized excesses of urban police forces in the twentieth century and after" as bearing characteristics of lynchings.[11]

Lynching as a means to maintain white supremacy

editLines of continuity from slavery to present

editA major motive for lynchings, particularly in the South, was white society's efforts to maintain white supremacy after the emancipation of enslaved people following the American Civil War. Lynchings punished perceived violations of customs, later institutionalized as Jim Crow laws, which mandated racial segregation of Whites and Blacks, and second-class status for Blacks. A 2017 paper found that more racially segregated counties were more likely to be places where Whites conducted lynchings.[12]

Lynchings emphasized the new social order which was constructed under Jim Crow; Whites acted together, reinforcing their collective identity along with the unequal status of Blacks through these group acts of violence.[13]

Lynchings were also (in part) intended as a voter suppression tool. A 2019 study found that lynchings occurred more frequently in proximity to elections, in particular in areas where the Democratic Party faced challenges.[14]

Tuskegee definition

editTuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University, defined conditions that constituted a recognized lynching, a definition which became generally accepted by other compilers of the era:

1. There must be legal evidence that a person was killed.

2. That person must have met death illegally.

3. A group of three or more persons must have participated in the killing.

4. The group must have acted under the pretext of service to justice, race, or tradition.[15][16]

Statistics

editStatistics for lynchings have traditionally come from three sources primarily, none of which covered the entire historical time period of lynching in the United States. Before 1882, no contemporaneous statistics were assembled on a national level. In 1882, the Chicago Tribune began to systematically tabulate lynchings nationally. In 1908, the Tuskegee Institute began a systematic collection of lynching reports under the direction of Monroe Work at its Department of Records, drawn primarily from newspaper reports. Monroe Work published his first independent tabulations in 1910, although his report also went back to the starting year 1882.[17] Finally, in 1912, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People started an independent record of lynchings. The numbers of lynchings from each source vary slightly, with the Tuskegee Institute's figures being considered "conservative" by some historians.[18]

Based on the source, the numbers vary depending on the sources which are cited, the years which are considered by those sources, and the definitions which are given to specific incidents by those sources. The Tuskegee Institute has recorded the lynchings of 3,446 Blacks and the lynchings of 1,297 Whites, all of which occurred between 1882 and 1968, with the peak occurring in the 1890s, at a time of economic stress in the South and increasing political suppression of Blacks.[19] A six-year study published in 2017 by the Equal Justice Initiative found that 4,084 Black men, women, and children fell victim to "racial terror lynchings" in twelve Southern states between 1877 and 1950, besides 300 that took place in other states. During this period, Mississippi's 654 lynchings led the lynchings which occurred in all of the Southern states.[20][3][21]

The records of Tuskegee Institute remain the single most complete source of statistics and records on this crime since 1882 for all states, although modern research has illuminated new incidents in studies focused on specific states in isolation.[16] As of 1959, which was the last time that Tuskegee Institute's annual report was published, a total of 4,733 persons had died by lynching since 1882. The last lynching recorded by the Tuskegee Institute was that of Emmett Till in 1955. In the 65 years leading up to 1947, at least one lynching was reported every year. The period from 1882 to 1901 saw the height of lynchings, with an average of over 150 each year. 1892 saw the most number of lynchings in a year: 231 or 3.25 per one million people. After 1924 cases steadily declined, with less than 30 a year.[22][23][24] The decreasing rate of yearly lynchings was faster outside the South and for white victims of lynching. Lynching became more of a Southern phenomenon and a racial one that overwhelmingly affected Black victims.[25] There were measurable variations in lynching rates between and within states.[26]

| State | No. of victims per 100,000 |

|---|---|

| Mississippi | 52.8 |

| Georgia | 41.8 |

| Louisiana | 43.7 |

| Alabama | 32.4 |

| South Carolina | 18.8 |

| Florida | 79.8 |

| Tennessee | 38.4 |

| Arkansas | 42.6 |

| Kentucky | 45.7 |

| North Carolina | 11.0 |

According to the Tuskegee Institute, 38% of victims of lynching were accused of murder, 16% of rape, 7% for attempted rape, 6% were accused of felonious assault, 7% for theft, 2% for insult to white people, and 24% were accused of miscellaneous offenses or no offense.[25] In 1940, sociologist Arthur F. Raper investigated one hundred lynchings after 1929 and estimated that approximately one-third of the victims were falsely accused.[25]

Tuskegee Institute's method of categorizing most lynching victims as either Black or white in publications and data summaries meant that the murders of some minority and immigrant groups were obscured. In the West, for instance, Mexican, Native Americans, and Chinese were more frequent targets of lynchings than were African Americans, but their deaths were included among those of other Whites. Similarly, although Italian immigrants were the focus of violence in Louisiana when they started arriving in greater numbers, their deaths were not tabulated separately from Whites. In earlier years, Whites who were subject to lynching were often targeted because of suspected political activities or support of freedmen, but they were generally considered members of the community in a way new immigrants were not.[27]

Other victims included white immigrants, and, in the Southwest, Latinos. Of the 468 lynching victims in Texas between 1885 and 1942, 339 were Black, 77 white, 53 Hispanic, and 1 Native American.[28]

There were also Black-on-Black lynchings, with 125 recorded between 1882 and 1903, and there were four incidences of Whites being killed by Black mobs. The rate of Black-on-Black lynchings rose and fell in similar pattern of overall lynchings. There were also over 200 cases of white-on-white lynchings in the South before 1930.[24]

Conclusions of numerous studies since the mid-20th century have found the following variables affecting the rate of lynchings in the South: "lynchings were more numerous where the African American population was relatively large, the agricultural economy was based predominantly on cotton, the white population was economically stressed, the Democratic Party was stronger, and multiple religious organizations competed for congregants."[29]

Reconstruction (1865–1877)

editAfter the American Civil War, southern Whites struggled to maintain their dominance. Secret vigilante and terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings in order to discourage freedmen from voting, working, and getting educated.[18][31][32][33][34][35][36] They also sometimes attacked Northerners, teachers, and agents of the Freedmen's Bureau. The magnitude of the extralegal violence which occurred during election campaigns reached epidemic proportions, leading the historian William Gillette to label it "guerrilla warfare",[31][32][33][34][35] and historian Thomas E. Smith to understand it as a form of "colonial violence".[37]

The lynchers sometimes murdered their victims, but sometimes whipped or physically assaulted them to remind them of their former status as slaves.[38] Often night-time raids of African American homes were made in order to confiscate firearms. Lynchings to prevent freedmen and their allies from voting and bearing arms were extralegal ways of trying to enforce the previous system of social dominance and the Black Codes, which had been invalidated by the 14th and 15th Amendments in 1868 and 1870.

Journalist, educator, and civil rights leader, Ida B. Wells commented in an 1892 pamphlet she published called Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases that, "The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense."[39] A study published in August 2022 by researchers from Clemson University has stated that, "...rates of Black lynching decreased with greater Black firearm access..."[40]

From the mid-1870s onward, violence rose as insurgent paramilitary groups in the Deep South worked to suppress Black voting and turn Republicans out of office. In Louisiana, the Carolinas, and Florida especially, the Democratic Party relied on paramilitary "White Line" groups, such as the White Camelia, White League and Red Shirts to terrorize, intimidate and assassinate African-American and white Republicans in an organized drive to regain power. In Mississippi and the Carolinas, paramilitary chapters of Red Shirts conducted overt violence and disruption of elections. In Louisiana, the White League had numerous chapters; they carried out goals of the Democratic Party to suppress Black voting. Grant's desire to keep Ohio in the Republican aisle and his attorney general's maneuvers led to a failure to support the Mississippi governor with Federal troops.[41] The campaign of terror worked. In Yazoo County, Mississippi, for instance, with an African American population of 12,000, only seven votes were cast for Republicans in 1874. In 1875, Democrats swept into power in the Mississippi state legislature.[41]

Jim Crow era

editLynching attacks on African Americans, especially in the South, increased dramatically in the aftermath of Reconstruction. The peak of lynchings occurred in 1892, after White Southern Democrats had regained control of state legislatures. Many incidents were related to economic troubles and competition. At the turn of the 20th century, southern states passed new constitutions or legislation which effectively disenfranchised most Black people and many Poor Whites, established segregation of public facilities by race, and separated Black people from common public life and facilities through Jim Crow laws. The rate of lynchings in the South has been strongly associated with economic strains,[44] although the causal nature of this link is unclear.[45] Low cotton prices, inflation, and economic stress are associated with higher frequencies of lynching.

Georgia led the nation in lynchings from 1900 to 1931, with 302 incidents, according to The Tuskegee Institute. However, Florida led the nation in lynchings per capita from 1900 to 1930.[46][47][48] Lynchings peaked in many areas when it was time for landowners to settle accounts with sharecroppers.[49]

The frequency of lynchings rose during years of poor economy and low prices for cotton, demonstrating that more than social tensions generated the catalysts for mob action against the underclass.[44] Researchers have studied various models to determine what motivated lynchings. One study of lynching rates of Blacks in Southern counties between 1889 and 1931 found a relation to the concentration of Blacks in parts of the Deep South: where the Black population was concentrated, lynching rates were higher. Such areas also had a particular mix of socioeconomic conditions, with a high dependence on cotton cultivation.[50]

Henry Smith, an African American handyman accused of murdering a policeman's daughter, was a noted lynching victim because of the ferocity of the attack against him and the huge crowd that gathered.[51] He was lynched at Paris, Texas, in 1893 for killing Myrtle Vance, the three-year-old daughter of a Texas policeman, after the policeman had assaulted Smith.[52] Smith was not tried in a court of law. A large crowd followed the lynching, as was common then in the style of public executions. Henry Smith was fastened to a wooden platform, tortured for 50 minutes by red-hot iron brands, and burned alive while more than 10,000 spectators cheered.[51]

Fewer than one percent of lynch mob participants were ever convicted by local courts and they were seldom prosecuted or brought to trial. By the late 19th century, trial juries in most of the southern United States were all white because African Americans had been disenfranchised, and only registered voters could serve as jurors. Often juries never let the matter go past the inquest.

Such cases happened in the North as well. In 1892, a police officer in Port Jervis, New York, tried to stop the lynching of a Black man who had been wrongfully accused of assaulting a white woman. The mob responded by putting the noose around the officer's neck as a way of scaring him, and completed killing the other man. Although at the inquest the officer identified eight people who had participated in the lynching, including the former chief of police, the jury determined that the murder had been carried out "by person or persons unknown".[53]

In Duluth, Minnesota, on June 15, 1920, three young African American traveling circus workers were lynched after having been accused of having raped a white woman and were jailed pending a grand jury hearing. A physician's subsequent examination of the woman found no evidence of rape or assault.[further explanation needed][54]

In 1903, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported a new, popular make-believe children's game: "The Game of Lynching". "Imaginary mayor gives order not to harm imaginary mob, and an imaginary hanging follows. Fire contributes realistic touch." "It has crowded out baseball", and if it continues, "may deprive of some of its prestige the game of football".[55]

The new Ku Klux Klan

editD. W. Griffith's 1915 film, The Birth of a Nation, glorified the original Ku Klux Klan as protecting white southern women during Reconstruction, which he portrayed as a time of violence and corruption, following the Dunning School's interpretation of history. The film aroused great controversy. It was popular among Whites nationwide, but it was protested against by Black activists, the NAACP and other civil rights groups.[56][57]

On November 25, 1915, a group of men led by William J. Simmons burned a cross on top of Stone Mountain, inaugurating the revival of the Ku Klux Klan. The event was attended by 15 charter members and a few aging former members of the original Klan.[58]

The Klan and their use of lynching was supported by some public officials like John Trotwood Moore, the State Librarian and Archivist of Tennessee from 1919 to 1929.[59] Moore "became one of the South's more strident advocates of lynching".[59]

1919 was one of the worst years for lynching with at least seventy-six people killed in mob or vigilante related violence. Of these, more than eleven African American veterans who had served in the recently completed war were lynched in that year.[60]: 232 White supremacist violence culminated in the 1921 Tulsa race massacre in which the majority-Black Greenwood District was razed to the ground.

The NAACP mounted a strong nationwide campaign of protests and public education against The Birth of a Nation. As a result, some city governments prohibited the release of the film. In addition, the NAACP publicized production and helped create audiences for the 1919 releases, The Birth of a Race and Within Our Gates, African American–directed films that presented more positive images of blacks.

During and after the Great Depression

editWhile the frequency of lynching dropped in the 1930s, there was a spike in 1930 during the Great Depression. For example, in North Texas and southern Oklahoma alone, four people were lynched in separate incidents in less than a month. A spike in lynchings occurred after World War II, as tensions arose after veterans returned home. White people tried to re-impose white supremacy over returning Black veterans. The last documented mass lynching occurred in Walton County, Georgia, in 1946, when local white landowners killed two war veterans and their wives.

Soviet media frequently covered racial discrimination in the U.S.[61] Deeming American criticism of Soviet Union human rights abuses at this time as hypocrisy, the Russians responded with "And you are lynching Negroes".[62] In Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (2001), the historian Mary L. Dudziak wrote that Soviet communist criticism of racial discrimination and violence in the United States influenced the federal government to support civil rights legislation.[63]

Most lynchings ceased by the 1960s.[19][64] However, in 2021 there were claims that racist lynchings still happen in the United States, being covered up as suicides.[65]

Justifications of lynchings

editOpponents of legislation often said lynchings prevented murder and rape. As documented by Ida B. Wells, the most prevalent accusation against lynching victims was murder or attempted murder. Rape charges or rumors were present in less than one-third of the lynchings; such charges were often pretexts for lynching Blacks who violated Jim Crow etiquette or engaged in economic competition with Whites. Other common reasons given included arson, theft, assault, and robbery; sexual transgressions (miscegenation, adultery, cohabitation); "race prejudice", "race hatred", "racial disturbance"; informing on others; "threats against whites"; and violations of the color line ("attending white girl", "proposals to white woman").[66]

Although the rhetoric which surrounded lynchings frequently suggested that they were carried out in order to protect the virtue and safety of white women, the actions basically arose out of white attempts to maintain domination in a rapidly changing society and their fears of social change.[18]

Mobs usually alleged crimes for which they lynched Black people. In the late 19th century, however, journalist Ida B. Wells showed that many presumed crimes were either exaggerated or had not even occurred.[67]

The ideology behind lynching, directly connected to the denial of political and social equality, was stated forthrightly in 1900 by United States Senator Benjamin Tillman, who was previously governor of South Carolina:

We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.[68][69]

Lynchings declined briefly after White supremacists, the so-called "Redeemers", took over the governments of the southern states in the 1870s. By the end of the 19th century, with struggles over labor and disenfranchisement, and continuing agricultural depression, lynchings rose again. Between 1882 and 1968, the Tuskegee Institute recorded 1,297 lynchings of white people and 3,446 lynchings of Black people.[71][72] Lynchings were concentrated in the Cotton Belt (Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, Texas, and Louisiana).[73][74]However, lynchings of Mexicans were under-counted in the Tuskegee Institute's records,[75] and some of the largest mass lynchings in American history were the Chinese massacre of 1871 and the lynching of eleven Italian immigrants in 1891 in New Orleans.[76] During the California Gold Rush, White resentment towards more successful Mexican and Chilean miners resulted in the lynching of at least 160 Mexicans between 1848 and 1860.[77][78]

Members of mobs that participated in lynchings often took photographs of what they had done to their victims in order to spread awareness and fear of their power. Souvenir taking, such as pieces of rope, clothing, branches, and sometimes body parts was not uncommon. Some of those photographs were published and sold as postcards. In 2000, James Allen published a collection of 145 lynching photos in book form as well as online,[79] with written words and video to accompany the images.

The murders reflected the tensions of labor and social changes, as the Whites imposed Jim Crow rules, legal segregation and white supremacy. The lynchings were also an indicator of long economic stress due to falling cotton prices through much of the 19th century, as well as financial depression in the 1890s. In the Mississippi bottomlands, for instance, lynchings rose when crops and accounts were supposed to be settled.[49]

In the Mississippi Delta region

editThe late 1800s and early 1900s in the Mississippi Delta showed both frontier influence and actions directed at repressing African Americans. After the Civil War, 90% of the Delta was still undeveloped.[49] Both Whites and Blacks migrated there for a chance to buy land in the backcountry. It was frontier wilderness, heavily forested and without roads for years.[49] Before the start of the 20th century, lynchings often took the form of frontier justice directed at transient workers as well as residents.[49] Thousands of workers were brought in by planters to do lumbering and work on levees.[citation needed]

Whites accounted for just over 12 percent of the Delta region's population, but made up nearly 17 percent of lynching victims. So, in this region, they were lynched at a rate that was over 35 percent higher than their proportion in the population, primarily due to being accused of crimes against property (chiefly theft). Conversely, Blacks were lynched at a rate, in the Delta, lesser than their proportion of the population. This was unlike the rest of the South, where Blacks comprised the majority of lynching victims. In the Delta, they were most often accused of murder or attempted murder, in half the cases, and 15 percent of the time, they were accused of rape, meaning that another 15 percent of the time they were accused of a combination of rape and murder, or rape and attempted murder.[49]

A clear seasonal pattern to lynchings existed with colder months being the deadliest. As noted, cotton prices fell during the 1880s and 1890s, increasing economic pressures. "From September through December, the cotton was picked, debts were revealed, and profits (or losses) realized... Whether concluding old contracts or discussing new arrangements, [landlords and tenants] frequently came into conflict in these months and sometimes fell to blows."[49] During the winter, murder was most cited as a cause for lynching. After 1901, as economics shifted and more Blacks became renters and sharecroppers in the Delta, with few exceptions, only African Americans were lynched. The frequency increased from 1901 to 1908 after African Americans were disfranchised. "In the twentieth century Delta vigilantism finally became predictably joined to white supremacy."[80]

Other ethnicities

editAccording to the Tuskegee Institute, of the 4,743 people lynched between 1882 and 1968, 1,297 were listed as "white". The Tuskegee Institute, which kept the most complete records, documented victims internally as "Negro", "white", "Chinese", and occasionally as "Mexican" or "Indian", but merged these into only two categories of Black or white in the tallies it published. Mexican, Chinese, and Native American lynching victims were tallied as white. Particularly in the West, minorities such as Chinese, Native Americans, Mexicans, and others were also lynching victims. The lynching of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the Southwest was long overlooked in American history, when attention was focused on the treatment of African Americans in the South.[23][27][81]

In modern scholarship, researchers estimate that 597 Mexicans were lynched between 1848 and 1928. Mexicans were lynched at a rate of 27.4 per 100,000 of population between 1880 and 1930. This statistic was second only to that of the African American community, which endured an average of 37.1 per 100,000 of population during that period. Between 1848 and 1879, Mexicans were lynched at an unprecedented rate of 473 per 100,000 of population.[27]

After their increased immigration to the U.S. in the late 19th century, Italian Americans in the South were recruited for laboring jobs. On March 14, 1891, 11 Italian immigrants were lynched in New Orleans, Louisiana.[82] This incident was one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history.[83] A total of twenty Italians were lynched during the 1890s. Although most lynchings of Italian Americans occurred in the South, Italians did not comprise a major portion of immigrants or a major portion of the population as a whole. Isolated lynchings of Italians also occurred in New York, Pennsylvania, and Colorado.

On February 21, 1909, a riot targeting Greek Americans occurred in Omaha, Nebraska. Many Greeks were looted, beaten and businesses were burnt.

In 1915, Leo Frank, an American Jew, was lynched near Atlanta, Georgia. In 1913, Frank had been convicted of the murder of Mary Phagan, a thirteen-year-old girl who was employed by his pencil factory. A series of appeals were filed on behalf of Frank, but all of them were denied. The final appeal was denied after a 7–2 decision was made by the U.S. Supreme Court. After Governor John M. Slaton commuted Frank's sentence to life imprisonment, a group of men, calling themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan, kidnapped Frank from a prison farm in Milledgeville in a planned event that included cutting the prison's telephone wires. They transported him 175 miles back to Marietta, near Atlanta, where they lynched him in front of a mob.

After the lynching of Leo Frank, around half of Georgia's 3,000 Jews left the state.[84] According to author Steve Oney, "What it did to Southern Jews can't be discounted... It drove them into a state of denial about their Judaism. They became even more assimilated, anti-Israel, Episcopalian. The Temple did away with chupahs at weddings – anything that would draw attention."[85]

Between the 1830s and 1850s, the majority of those lynched were Whites. More Whites were lynched than Blacks for the years 1882–1885. By 1890s, the number of Blacks lynched yearly grew to a number significantly more than that of Whites, and the vast majority of victims were Black from then on. White people were mostly lynched in the Western states and territories, although there were over 200 cases in the South. According to the Tuskegee Institute, in 1884 near Georgetown, Colorado, there was one instance of 17 "unknown white men" being hanged as cattle thieves in a single day. In the West, lynchings were often done to establish law and order.[18][19][24]

Spectacle lynching and racist memorabilia

editLynching was often treated as a spectator sport, where large crowds gathered to partake in or watch the torture and mutilation of the victim(s). The attendants often treated these as festive events, with food, family photos, and souvenirs.[86] Whites used these events to demonstrate their power and control. This often led to the exodus of the remaining Black population and discouraged future settlement.[3]

In the post–Reconstruction era, lynching photographs were printed for various purposes, including postcards, newspapers, and event mementos.[87] Typically these images depicted an African American lynching victim and all or part of the crowd in attendance. Spectators often included women and children. The perpetrators of lynchings were not identified.[88] The 1916 lynching of Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas, drew nearly 15,000 spectators.[87] Often lynchings were advertised in newspapers prior to the event in order to give photographers time to arrive early and prepare their camera equipment.[89]

Photographic records and postcards

editAt the start of the 20th century in the United States, lynching was photographic sport. People sent picture postcards of lynchings they had witnessed. A writer for Time magazine noted in 2000,

Even the Nazis did not stoop to selling souvenirs of Auschwitz, but lynching scenes became a burgeoning subdepartment of the postcard industry. By 1908, the trade had grown so large, and the practice of sending postcards featuring the victims of mob murderers had become so repugnant, that the U.S. Postmaster General banned the cards from the mails.[90]

After the lynching, photographers would sell their pictures as-is or as postcards, sometimes costing as much as fifty cents a piece, or $9, as of 2016.[88] Though some photographs were sold as plain prints, others contained captions. These captions were either straightforward details—such as the time, date and reasons for the lynching—while others contained polemics or poems with racist or otherwise threatening remarks.[89] An example of this is a photographic postcard attached to the poem "Dogwood Tree", which says: "The negro now/By eternal grace/Must learn to stay in the negro's place/In the Sunny South, the land of the Free/Let the WHITE SUPREME forever be."[92] Such postcards with explicit rhetoric such as "Dogwood Tree" were typically circulated privately or mailed in a sealed envelope.[93] Other times these pictures simply included the word "WARNING".[89]

In 1873, the Comstock Act was passed, which banned the publication of "obscene matter as well as its circulation in the mails".[89] In 1908, Section 3893 was added to the Comstock Act, stating that the ban included material "tending to incite arson, murder, or assassination".[89] Although this act did not explicitly ban lynching photographs or postcards, it banned the explicit racist texts and poems inscribed on certain prints. According to some, these texts were deemed "more incriminating" and caused their removal from the mail instead of the photograph itself because the text made "too explicit what was always implicit in lynchings".[89] Some towns imposed "self-censorship" on lynching photographs, but section 3893 was the first step towards a national censorship.[89] Despite the amendment, the distribution of lynching photographs and postcards continued. Though they were not sold openly, the censorship was bypassed when people sent the material in envelopes or mail wrappers.[93]

Resistance

editAfrican American resistance

editAfrican Americans resisted lynchings in numerous ways. Intellectuals and journalists encouraged public education, actively protesting and lobbying against lynch mob violence and government complicity. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and related groups, organized support from white and Black Americans, publicizing injustices, investigating incidents, and working for passage of federal anti-lynching legislation (which finally passed as the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act on March 29, 2022).[94] African American women's clubs raised funds and conducted petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings, and demonstrations to highlight the issues and combat lynching.[95] In the great migration, particularly from 1910 to 1940, 1.5 million African Americans left the South, primarily for destinations in northern and mid-western cities, both to gain better jobs and education and to escape the high rate of violence. From 1910 to 1930 particularly, more Blacks migrated from counties with high numbers of lynchings.[96]

African American writers used their talents in numerous ways to publicize and protest against lynching. In 1914, Angelina Weld Grimké had already written her play Rachel to address racial violence. It was produced in 1916. In 1915, W. E. B. Du Bois, noted scholar and head of the recently formed NAACP, called for more Black-authored plays.

African American female playwrights were strong in responding. They wrote ten of the 14 anti-lynching plays produced between 1916 and 1935. The NAACP set up a Drama Committee to encourage such work. In addition, Howard University, the leading historically Black college, established a theater department in 1920 to encourage African American dramatists. Starting in 1924, the NAACP's major publications The Crisis and Opportunity sponsored contests to encourage Black literary production.[97]

African Americans emerged from the Civil War with the political experience and stature to resist attacks, but disfranchisement and imposition of Jim Crow in the South at the turn of the 20th century closed them out of the political system and judicial system in many ways. Advocacy organizations compiled statistics and publicized the atrocities, as well as working for enforcement of civil rights and a federal anti-lynching law. From the early 1880s, the Chicago Tribune reprinted accounts of lynchings from other newspapers, and published annual statistics. These provided the main source for the compilations by the Tuskegee Institute to document lynchings, a practice it continued until 1968.[98]

In 1892, journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett was shocked when three friends in Memphis, Tennessee, were lynched. She learned it was because their grocery store had competed successfully against a white-owned store. Outraged, Wells-Barnett began a global anti-lynching campaign that raised awareness of these murders. She also investigated lynchings and overturned the common idea that they were based on Black sexual crimes, as was popularly discussed; she found lynchings were more an effort to suppress Blacks who competed economically with Whites, especially if they were successful. As a result of her efforts at education, Black women in the U.S. became active in the anti-lynching crusade, often in the form of clubs that raised money to publicize the abuses. When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in 1909, Wells became part of its multi-racial leadership and continued to be active against lynching. The NAACP began to publish lynching statistics at their office in New York City.

In 1898, Alexander Manly of Wilmington, North Carolina, directly challenged popular ideas about lynching in an editorial in his newspaper The Daily Record. He noted that consensual relationships took place between white women and Black men, and said that many of the latter had white fathers (as he did). His references to miscegenation lifted the veil of denial. Whites were outraged. A mob destroyed his printing press and business, ran Black leaders out of town and killed many others, and overturned the biracial Populist-Republican city government, headed by a white mayor and majority-white council. Manly escaped, eventually settling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In 1903, writer Charles W. Chesnutt of Ohio published the article "The Disfranchisement of the Negro", detailing civil rights abuses as Southern states passed laws and constitutions that essentially disfranchised African Americans, excluding them wholesale from the political system. He publicized the need for change in the South. Numerous writers appealed to the literate public.[99]

In 1904, Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, published an article in the magazine North American Review to respond to Southerner Thomas Nelson Page. She analyzed and refuted with data his attempted justification of lynching as a response to assaults by Black men on white women. Terrell showed how apologists like Page had tried to rationalize what were violent mob actions that were seldom based on assaults.[101] African-American newspapers such as the Chicago Illinois newspaper The Chicago Whip[102] and the NAACP magazine The Crisis would not just merely report lynchings, they would denounce them as well. Indeed in 1919, the NAACP would publish "Thirty Years of Lynching" and hang a black flag outside its office.[citation needed]

African American resistance to lynching carried substantial risks. In 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a group of 75 African American citizens attempted to stop a lynch mob from taking 19-year-old assault suspect Dick Rowland out of jail. In a scuffle between a white man and an armed African American veteran, the white man was shot, leading to a shootout between the two groups, which left 2 African Americans and 10 Whites dead. Whites retaliated by rioting, during which they burned 1,256 homes and as many as 200 businesses in the segregated Greenwood district, destroying what had been a thriving area. A 2001 state commission confirmed 39 dead, 26 Black and 13 white deaths. The commission gave several estimates ranging from 75 to 300 total dead.[103] Rowland was saved, however, and was later exonerated.

The growing networks of African American women's club groups were instrumental in raising funds to support the NAACP's public education and lobbying campaigns. They also built community organizations. In 1922, Mary Talbert headed the anti-lynching crusade to create an integrated women's movement against lynching.[101] It was affiliated with the NAACP, which mounted a multi-faceted campaign. For years the NAACP used petition drives, letters to newspapers, articles, posters, lobbying Congress, and marches to protest against the abuses in the South and keep the issue before the public.

A 2022 study found that African American communities that had increased access to firearms were less likely to be lynched. The study authors write, "In states and years in which Black residents had more access to firearms, there were fewer lynchings... In all three estimation strategy variants, the estimated negative effect of Black firearm access on lynchings is quite large and statistically significant. An increase of one standard deviation in firearm access, for example, is associated with a reduction in lynchings of between 0.8 and 1.4 per year, about half a standard deviation."[104]

Resistance by Southern white women

editIn 1930, Southern white women responded in large numbers to the leadership of Jessie Daniel Ames in forming the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. She and her co-founders obtained the signatures of 40,000 women to their pledge against lynching and for a change in the South. The pledge included the statement:

In light of the facts we dare no longer to... allow those bent upon personal revenge and savagery to commit acts of violence and lawlessness in the name of women.

Despite physical threats and hostile opposition, the women leaders persisted with petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings, and demonstrations to highlight the issues.[95] By the 1930s, the number of lynchings had dropped to about ten per year in Southern states.

Religious leaders

editCardinal James Gibbons in October 1905 condemned lynching, calling it a blot on American civilization and against the teaching of Jesus Christ.[105]

Great Migration

editThe rapid influx of Blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern cities, exacerbating hostility between Black and white Northerners. The Red Summer of 1919 was marked by hundreds of deaths and higher casualties across the U.S. as a result of race riots that occurred in more than three dozen cities, such as the Chicago race riot of 1919 and the Omaha race riot of 1919.[106]

Federal legislation inhibited by the Solid South

editAt the turn of the century there was a concerted Republican effort to restrict the South's apportionment of seats[107] and to set aside cases election results due to black disenfranchisement. These efforts failed.

President Theodore Roosevelt made public statements against lynching in 1903, following George White's murder in Delaware, and in the 1906 State of the Union Address on December 4, 1906. When Roosevelt suggested that lynching was taking place in the Philippines, Southern senators (all white Democrats) demonstrated their power by a filibuster in 1902 during review of the "Philippines Bill". In 1903, Roosevelt refrained from commenting on lynching during his Southern political campaigns.

Roosevelt's efforts cost him political support among white people, especially in the South. Threats against him increased so that the Secret Service added to the size of his bodyguard detail.[108]

From 1882 to 1968, "nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, and three of them passed the House. Seven presidents between 1890 and 1952 petitioned Congress to pass a federal law."[109] None succeeded in gaining passage, blocked by the Southern Caucus — the delegation of powerful white Southerners in the Senate, which controlled, due to seniority, many of the powerful committee chairmanships.[109] In 2005, by a resolution sponsored by senators Mary Landrieu of Louisiana and George Allen of Virginia, and passed by voice vote, the Senate made a formal apology for its failure to pass an anti-lynching law "when it was most needed".[109]

Dyer Bill

editThe Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was first introduced to the United States Congress on April 1, 1918, by Republican Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis, Missouri in the U.S. House of Representatives. Rep. Dyer was concerned over increased lynching, mob violence, and disregard for the "rule of law" in the South. The bill made lynching a federal crime, and those who participated in lynching would be prosecuted by the federal government. It did not pass due to a Southern filibuster. In 1919, the new NAACP organized the National Conference on Lynching to increase support for the Dyer Bill.

The bill was passed by the United States House of Representatives in 1922, and in the same year it was given a favorable report by the United States Senate Committee. Its passage was blocked by White Democratic senators from the Solid South, the only representatives elected since the southern states had disfranchised African Americans around the start of the 20th century.[110] The Dyer Bill influenced later anti-lynching legislation, including the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which was also defeated in the US Senate.[111]

As passed by the House, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill stated:

"To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching.... Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the phrase 'mob or riotous assemblage,' when used in this act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more persons acting in concert for the purpose of depriving any person of his life without authority of law as a punishment for or to prevent the commission of some actual or supposed public offense."[112]

In 1920, the Black community succeeded in getting its most important priority in the Republican Party's platform at the National Convention: support for an anti-lynching bill. The Black community supported Warren G. Harding in that election, but were disappointed as his administration moved slowly on a bill.[113]

Dyer revised his bill and re-introduced it to the House in 1921. It passed the House, 230 to 119,[114] on January 26, 1922, due to "insistent country-wide demand",[113] and was favorably reported out by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Action in the Senate was delayed, and ultimately the Democratic Solid South filibuster defeated the bill in the Senate in December.[115] In 1923, Dyer went on a Midwestern and Western state tour promoting the anti-lynching bill; he praised the NAACP's work for continuing to publicize lynching in the South and for supporting the federal bill. Dyer's anti-lynching motto was "We have just begun to fight", and he helped generate additional national support. His bill was defeated twice more in the Senate by Southern Democratic filibuster. The Republicans were unable to pass a bill in the 1920s.[116]

Roosevelt presidency

editAnti-lynching advocates such as Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White campaigned for presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. They hoped he would lend public support to their efforts against lynching. Senators Robert F. Wagner and Edward P. Costigan drafted the Costigan–Wagner Bill in 1934 to require local authorities to protect prisoners from lynch mobs. Like the Dyer Bill, it made lynching a Federal crime in order to take it out of state administration.

Southerners had a disproportionate influence on Congress. Because of the Southern Democrats' disfranchisement of African Americans in Southern states at the start of the 20th century, Southern Whites for decades had nearly double the representation in Congress beyond their own population. Southern states had Congressional representation based on total population, but essentially only Whites could vote and only their issues were supported. Due to seniority achieved through one-party Democratic rule in their region, Southern Democrats controlled many important committees in both houses. As a result, Southern white Democrats were a formidable power in Congress until the 1960s and they consistently opposed any legislation related to putting lynching under Federal oversight.

In the 1930s, virtually all Southern senators blocked the proposed Costigan–Wagner Bill. Southern senators used a filibuster to prevent a vote on the bill. Some Republican senators, such as the conservative William Borah from Idaho, opposed the bill for constitutional reasons (he had also opposed the Dyer Bill). He felt it encroached on state sovereignty and, by the 1930s, thought that social conditions had changed so that the bill was less needed.[117] He spoke at length in opposition to the bill in 1935 and 1938. 1934 saw 15 lynchings of African Americans with 21 lynchings in 1935, 8 in 1936, and 2 in 1939.

A lynching in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, changed the political climate in Washington.[118] On July 19, 1935, Rubin Stacy, a homeless African-American tenant farmer, knocked on doors begging for food. After resident complaints, deputies took Stacy into custody. While he was in custody, a lynch mob took Stacy from the deputies and murdered him. Although the faces of his murderers could be seen in a photo taken at the lynching site, the state did not prosecute the murder.[119]

Stacy's murder galvanized anti-lynching activists, but President Roosevelt did not support the federal anti-lynching bill. He feared that support would cost him Southern votes in the 1936 election.

In 1937, the lynching of Roosevelt Townes and Robert McDaniels gained national publicity, and its brutality was widely condemned.[120] Such publicity enabled Joseph A. Gavagan (D-New York) to gain support for anti-lynching legislation he had put forward in the House of Representatives; it was supported in the Senate by Democrats Robert F. Wagner (New York) and Frederick Van Nuys (Indiana). The legislation eventually passed in the House, but the emerging Democratic Southern caucus blocked it in the Senate.[121][122] Senator Allen Ellender (D-Louisiana) proclaimed: "We shall at all cost preserve the white supremacy of America."[121]

In 1939, Roosevelt created the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department. It started prosecutions to combat lynching, but failed to win any convictions until 1946.[123]

Cold War period

editIn 1946, the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department gained its first conviction under federal civil rights laws against a lyncher. Florida constable Tom Crews was sentenced to a $1,000 fine (equivalent to $15,600 in 2023) and one year in prison for civil rights violations in the killing of an African-American farm worker.

In 1946, a mob of white men shot and killed two young African American couples near Moore's Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia, 60 miles east of Atlanta. This lynching of four young sharecroppers, one a World War II veteran, shocked the nation. The attack was a key factor in President Harry S. Truman's making civil rights a priority of his administration. Although the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigated the crime, they were unable to prosecute. It was the last documented lynching of so many people in one incident.[123]

In 1947, the Truman administration published a report entitled To Secure These Rights which advocated making lynching a federal crime, abolishing poll taxes, and other civil rights reforms. The Southern Democratic bloc of senators and congressmen continued to obstruct attempts at federal legislation.[124]

In the 1940s, the Klan openly criticized Truman for his efforts to promote civil rights. Later historians documented that Truman had briefly made an attempt to join the Klan as a young man in 1924, when it was near its peak of social influence in promoting itself as a fraternal organization. When a Klan officer demanded that Truman pledge not to hire any Catholics if he were re-elected as county judge, Truman refused. He personally knew their worth from his World War I experience. His membership fee was returned and he never joined the Klan.[citation needed][a]

International media, including the media in the Soviet Union, covered racial discrimination in the U.S.[128][129]

In a meeting with President Harry Truman in 1946, Paul Robeson urged him to take action against lynching. In 1951, Robeson and the Civil Rights Congress made a presentation entitled "We Charge Genocide" to the United Nations a document which argued that the U.S. government's failure to act against lynchings meant it was guilty of genocide under Article II of the United Nations Genocide Convention. Based on his commissions report To Secure There Rights, Truman introduced in Congress the first presidentially proposed comprehensive Civil Rights Bill - it included legislation making lynching a federal crime. The first year on record with no lynchings reported in the United States was 1952.[130]

In the early Cold War years, the FBI was worried more about possible communist connections among anti-lynching groups than about the lynching crimes. For instance, the FBI branded Albert Einstein a communist sympathizer for joining Robeson's American Crusade Against Lynching.[131]

Civil rights movement

editBy the 1950s, the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. Membership in the NAACP increased in states across the country. The NAACP achieved a significant U.S. Supreme Court victory in 1954 ruling that segregated education was unconstitutional. A 1955 lynching that sparked public outrage about injustice was that of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago. Spending the summer with relatives in Money, Mississippi, Till was killed by a mob of white men. Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out, and he was shot in the head before being thrown into the Tallahatchie River, his body weighed down with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His mother insisted on a public funeral with an open casket, to show people how badly Till's body had been disfigured. News photographs circulated around the country, and drew intense public reaction. The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the Black community throughout the U.S.[132] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-white jury.[133][134]

In the 1960s, the civil rights movement attracted students to the South from all over the country to work on voter registration and integration. The intervention of people from outside the communities and threat of social change aroused fear and resentment among many Whites. In June 1964, three civil rights workers disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. They had been investigating the arson of a Black church being used as a "Freedom School". Six weeks later, their bodies were found in a partially constructed dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi. James Chaney of Meridian, Mississippi, and Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman of New York City had been members of the Congress of Racial Equality. They had been dedicated to non-violent direct action against racial discrimination. The investigation also unearthed the bodies of numerous anonymous victims of past lynchings and murders.

The United States prosecuted 18 men for a Ku Klux Klan conspiracy to deprive the victims of their civil rights under 19th century federal law, in order to prosecute the crime in a federal court. Seven men were convicted but received light sentences, two men were released because of a deadlocked jury, and the remainder were acquitted. In 2005, 80-year-old Edgar Ray Killen, one of the men who had earlier gone free, was retried by the state of Mississippi, convicted of three counts of manslaughter in a new trial, and sentenced to 60 years in prison. Killen died in 2018 after serving 12+1⁄2 years.

Because of J. Edgar Hoover's and others' hostility to the civil rights movement, agents of the FBI resorted to outright lying to smear civil rights workers and other opponents of lynching. For example, the FBI leaked false information in the press about the lynching victim Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered in 1965 in Alabama. The FBI said Liuzzo had been a member of the Communist Party USA, had abandoned her five children, and was involved in sexual relationships with African Americans in the movement.[135]

After the civil rights movement

editAlthough lynchings have become rare following the civil rights movement and the resulting changes in American social norms, some lynchings have still occurred. In 1981, two Klan members in Alabama randomly selected a 19-year-old Black man, Michael Donald, and murdered him, in order to retaliate for a jury's acquittal of a Black man who was accused of murdering a white police officer. The Klansmen were caught, prosecuted, and convicted (one of the Klansmen, Henry Hayes, was sentenced to death and executed on June 6, 1997). A $7 million judgment in a civil suit against the Klan bankrupted the local Klan subgroup, the United Klans of America.[136]

In 1998, Shawn Allen Berry, Lawrence Russel Brewer, and ex-convict John William King murdered James Byrd Jr. in Jasper, Texas. Byrd was a 49-year-old father of three, who had accepted an early-morning ride home with the three men. They attacked him and dragged him to his death behind their truck.[137] The three men dumped their victim's mutilated remains in the town's segregated African-American cemetery and then went to a barbecue.[138] Local authorities immediately treated the murder as a hate crime and requested FBI assistance. The murderers (two of whom turned out to be members of a white supremacist prison gang) were caught and stood trial. Brewer and King were both sentenced to death (with Brewer being executed in 2011, and King being executed in 2019). Berry was sentenced to life in prison.

On June 13, 2005, the U.S. Senate formally apologized for its failure to enact a federal anti-lynching law in the early 20th century, "when it was most needed". Before the vote, Louisiana senator Mary Landrieu noted: "There may be no other injustice in American history for which the Senate so uniquely bears responsibility."[139] The resolution was passed on a voice vote with 80 senators cosponsoring, with Mississippians Thad Cochran and Trent Lott being among the twenty U.S. senators abstaining.[139] The resolution expressed "the deepest sympathies and most solemn regrets of the Senate to the descendants of victims of lynching, the ancestors of whom were deprived of life, human dignity and the constitutional protections accorded all citizens of the United States".[139]

In February 2014, a noose was placed on the statue of James Meredith, the first African American student at the University of Mississippi.[140] A number of nooses appeared in 2017, primarily in or near Washington, D.C.[141][142][143]

In August 2014, Lennon Lacy, a teenager from Bladenboro, North Carolina, who had been dating a white girl, was found dead, hanging from a swing set. His family believes that he was lynched, but the FBI stated, after an investigation, that it found no evidence of a hate crime. The case is featured in a 2019 documentary about lynching in America, Always in Season.[144]

In May 2017, Mississippi Republican state representative Karl Oliver of Winona stated that Louisiana lawmakers who supported the removal of Confederate monuments from their state should be lynched. Oliver's district includes Money, Mississippi, where Emmett Till was murdered in 1955. Mississippi's leaders from both the Republican and Democratic parties quickly condemned Oliver's statement.[145]

In 2018, the Senate attempted to pass new anti-lynching legislation (the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act), but this failed.

On April 26, 2018, in Montgomery, Alabama, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened. Founded by the Equal Justice Initiative of that city, it is the first memorial created specifically to document lynchings of African Americans.

In 2019, Goodloe Sutton, then editor of a small Alabama newspaper, The Democrat-Reporter, received national publicity after he said in an editorial that the Ku Klux Klan was needed to "clean up D.C."[146] When he was asked what he meant by "cleaning up D.C.", he stated: "We'll get the hemp ropes out, loop them over a tall limb and hang all of them." "When he was asked if he felt that it was appropriate for the publisher of a newspaper to call for the lynching of Americans, Sutton doubled down on his position by stating: …'It's not calling for the lynchings of Americans. These are socialist-communists we're talking about. Do you know what socialism and communism is?'" He denied that the Klan was a racist and violent organization, comparing it to the NAACP.[147]

On January 6, 2021, during the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol, the rioters shouted "Hang Mike Pence!" in an attempt to find and lynch the vice president of the United States for refusing to overturn the 2020 United States Presidential Election in favor of President Donald Trump, and a rudimentary gallows was built on the Capitol lawn.[148][149]

As of 2021, the Equal Justice Initiative claims that lynchings never stopped, listing 8 deaths in Mississippi that law-enforcement deemed suicides, but the civil rights organization Julian believes were lynchings. According to Jill Jefferson, "There is a pattern to how these cases are investigated", "When authorities arrive on the scene of a hanging, it's treated as a suicide almost immediately. The crime scene is not preserved. The investigation is shoddy. And then there is a formal ruling of suicide, despite evidence to the contrary. And the case is never heard from again unless someone brings it up."[150]

The West

editHistorians have debated the history of lynchings on the western frontier, which has been obscured by the mythology of the American Old West. In unorganized territories or sparsely settled states, law enforcement was limited, often provided only by a U.S. Marshal who might, despite the appointment of deputies, be hours, or days, away by horseback.

People often carried out lynchings in the Old West against accused criminals in custody. Lynching did not so much substitute for an absent legal system as constitute an alternative system dominated by a particular social class or racial group. Historian Michael J. Pfeifer writes, "Contrary to the popular understanding, early territorial lynching did not flow from an absence or distance of law enforcement but rather from the social instability of early communities and their contest for property, status, and the definition of social order."[151]

The exact number of people in the Western states/territories killed in lynchings is unknown. There were 571 lynchings of Mexicans between 1848 and 1928. The most recorded deaths were in Texas, with up to 232 killings, then followed by California (143 deaths), New Mexico (87 deaths), and Arizona (48 deaths). Lynch mobs killed Mexicans for a variety of reasons, with the most common accusations being murder and robbery. Others were killed as suspected bandits or rebels.[152]

California

editMany of the Mexicans who were native to what would become a state within the United States were experienced miners, and they had great success mining gold in California.[27] Their success aroused animosity by white prospectors, who intimidated Mexican miners with the threat of violence and committed violence against some. Between 1848 and 1860, white Americans lynched at least 163 Mexicans in California.[27] On July 5, 1851, a mob in Downieville, California, lynched a Mexican woman named Josefa Segovia.[153] She was accused of killing a white man who had attempted to assault her after breaking into her home.[154][155]

The San Francisco Vigilance Movement has traditionally been portrayed as a positive response to government corruption and rampant crime, but revisionist historians have argued that it created more lawlessness than it eliminated.[156] Four men were executed by the 1851 Committee of Vigilance before it disbanded. When the second Committee of Vigilance was instituted in 1856, in response to the murder of publisher James King of William, it hanged a total of four men, all accused of murder.[157]

During the same year of 1851, just after the beginning of the Gold Rush, these Committees lynched an unnamed thief in northern California. The Gold Rush and the economic prosperity of Mexican-born people was one of the main reasons for mob violence against them. Other factors include land and livestock, since they were also a form of economic success. In conjunction with lynching, mobs also attempted to expel Mexicans, and other groups such as the indigenous peoples of the region, from areas with great mining activity and gold. As a result of the violence against Mexicans, many formed bands of bandits and would raid towns. One case, in 1855, was when a group of bandits went into Rancheria and killed six people. When the news of this incident spread, a mob of 1,500 people formed, rounded up 38 Mexicans, and executed Puertanino.[who?] The mob also expelled all the Mexicans in Rancheria and nearby towns as well, burning their homes.[citation needed][158]

On October 24, 1871, a mob rampaged through Old Chinatown, Los Angeles and killed at least 18 Chinese Americans, after a white businessman had inadvertently been killed there in the crossfire of a tong battle within the Chinese community.

After the body of Brooke Hart was found on November 26, 1933, Thomas Harold Thurman and John Holmes, who had confessed to kidnapping and murdering Hart, were lynched on November 26 or November 27, 1933.[159][160]

Minnesota

editFour lynchings are included in a book of 12 case studies of the prosecution of homicides in the early years of statehood of Minnesota.[161] In 1858 the institutions of justice in the new state, such as jails, were scarce and the lynching of Charles J. Reinhart at Lexington on December 19 was not prosecuted. The following year, the lynching of Oscar Jackson at Minnehaha Falls on April 25 resulted in a later charging of Aymer Moore for the homicide.

In 1866, when Alexander Campbell and George Liscomb were lynched at Mankato on Christmas Day, the state returned an indictment of John Gut on September 18 the following year. Then in 1872 when Bobolink, a Native American, was accused and imprisoned pending trial in Saint Paul, the state avoided his lynching despite a public outcry against Natives.

Texas

edit"Lynching in Texas", a project of Sam Houston State University, maintains a database of over 600 lynchings committed in Texas between 1882 and 1942.[162] Many of the lynchings were of people of Mexican heritage.

During the early 1900s, hostilities between Anglos and Mexicans along the "Brown Belt" were common. In Rocksprings, Antonio Rodriguez, a Mexican, was burned at the stake. This event was widely publicized and protests against the treatment of Mexicans in the U.S. erupted within the interior of Mexico, namely in Guadalajara and Mexico City.[163]

Members of the Texas Rangers were charged in 1918 with the murder of Florencio Garcia. Two rangers had taken Garcia into custody for a theft investigation. The next day they let Garcia go, and were last seen escorting him on a mule. Garcia was never seen again. A month after the interrogation, bones and Garcia's clothing were found beside the road where the Rangers claimed to have let Garcia go. The Rangers were arrested for murder, freed on bail, and acquitted due to lack of evidence. The case became part of the Canales investigation into criminal conduct by the Rangers.[164]: 80

Arizona

editIn 1859, white settlers began to expel Mexicans from Arizona. The mob was able to chase Mexicans out of many towns, southward. Even though they were successful in doing so, the mob followed and killed many of the people that had been chased out. The Sonoita massacre was a result of these expulsions, where white settlers killed four Mexicans and one Native American.[citation needed]

On April 19, 1915, the Leon brothers were lynched by hanging in Pima Country by deputies Robert Fenter and Frank Moore. This lynching was unusual, since the perpetrators were arrested, tried, and convicted for the murders. Fenter and Moore were both found guilty of second degree murder and each sentenced to 10 years to life in prison. However, they were both pardoned by Governor George W. P. Hunt upon his departure from office in February 1917.[165][166]

Wyoming

editAnother well-documented episode in the history of the American West is the Johnson County War, a dispute in the 1890s over land use in Wyoming. Large-scale ranchers hired mercenaries to lynch the small ranchers.

Oregon

editAlonzo Tucker was a traveling boxer who was heading north from California to Washington. Part of his travels led him to stay in Coos Bay, Oregon, where he was lynched by a mob on September 18, 1902. He was accused by Mrs. Dennis for assault. After the lynching, Dennis and her family quickly left town and headed to California. Tucker is the only documented lynching of a Black man in Oregon.[167]

Other lynchings include many Native Americans.[168]

Laws

editFederal action

editFor most of the history of the United States, lynching was rarely prosecuted, as the same people who would have had to prosecute and sit on juries were generally on the side of the action or related to the perpetrators in the small communities where many lived. When the crime was prosecuted, it was under state murder statutes. In one example in 1907–09, the U.S. Supreme Court tried its only criminal case in history, 203 U.S. 563 (U.S. v. Sheriff Shipp). Shipp was found guilty of criminal contempt for doing nothing to stop the mob in Chattanooga, Tennessee that lynched Ed Johnson, who was in jail for rape.[169] In the South, Blacks generally were not able to serve on juries, as they could not vote, having been disfranchised by discriminatory voter registration and electoral rules passed by majority-white legislatures in the late 19th century, who also imposed Jim Crow laws.

Starting in 1909, federal legislators introduced more than 200 bills in Congress to make lynching a federal crime, but they failed to pass, chiefly because of Southern legislators' opposition.[170] Because Southern states had effectively disfranchised African Americans at the start of the 20th century, the white Southern Democrats controlled all the apportioned seats of the South, nearly double the Congressional representation that white residents alone would have been entitled to. They were a powerful voting bloc for decades and controlled important committee chairmanships. The Senate Democrats formed a bloc that filibustered for a week in December 1922, holding up all national business, to defeat the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. It had passed the House in January 1922 with broad support except for the South. Representative Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis, the chief sponsor, undertook a national speaking tour in support of the bill in 1923, but the Southern Senators defeated it twice more in the next two sessions.

Under the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department tried, but failed, to prosecute lynchers under Reconstruction era civil rights laws. The first successful federal prosecution of a lyncher for a civil rights violation was in 1946. By that time, the era of lynchings as a common occurrence had ended. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. succeeded in gaining House passage of an anti-lynching bill, but it was defeated in the Senate, still dominated by the Southern Democratic bloc, supported by its disfranchisement of Blacks.

On December 19, 2018, the U.S. Senate voted unanimously in favor of the "Justice for Victims of Lynching Act of 2018" which, for the first time in U.S. history, would make lynching a federal hate crime.[171][172] The legislation had been reintroduced to the Senate earlier that year as Senate Bill S. 3178 by the three African-American U.S. senators, Tim Scott, Kamala Harris, and Cory Booker.[173] As of June 2019[update] the bill, which failed to become law during the 115th U.S. Congress, had been reintroduced as the Emmett Till Antilynching Act. The House of Representatives voted 410–4 to pass it on February 26, 2020.[174]

As of June 4, 2020, while protests and civil unrest over the murder of George Floyd were occurring nationwide, the bill was being considered by the Senate, with Senator Rand Paul preventing the bill from being passed by unanimous consent. Paul opposed the passage of the bill because, according to Paul, the language was overly broad, included attacks which he believed were not extreme enough to qualify as "lynching". He stated that "this bill would cheapen the meaning of lynching by defining it so broadly as to include a minor bruise or abrasion," and he has proposed the inclusion of an amendment that would apply a "serious bodily injury standard" for a crime to be classified as a lynching.[175][176][177]

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer criticized Rand Paul's position, saying on Twitter that "it is shameful that one GOP Senator is standing in the way of seeing this bill become law." Senator Kamala Harris added that "Senator Paul is now trying to weaken a bill that was already passed – there's no reason for this" while speaking to have the amendment defeated.[177][175]

In 2022, the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act passed both chambers of Congress and President Joe Biden signed it into federal law on March 29 of that year.[178] The Act, proposed by Illinois House Representative Bobby L. Rush, is the first bill to make lynching a federal hate crime, despite over a century of failed attempts to pass an anti-lynching bill through Congress. Anyone who violates the terms of the bill will be penalized with a fine, a prison sentence of up to 30 years, or both.[94]

State laws

editIn 1933, California defined lynching, punishable by 2–4 years in prison, as "the taking by means of a riot of any person from the lawful custody of any peace officer", with the crime of "riot" defined as two or more people using violence or the threat of violence.[179] It does not refer to lynching homicide, and has been used to charge individuals who have tried to free someone in police custody – leading to controversy.[180][181] In 2015, Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation by Senator Holly Mitchell removing the word "lynching" from the state's criminal code without comment after it received unanimous approval in a vote by state lawmakers. Mitchell stated, "It's been said that strong words should be reserved for strong concepts, and 'lynching' has such a painful history for African Americans that the law should only use it for what it is – murder by mob." The law was otherwise unchanged.[179]

In 1899, Indiana passed anti-lynching legislation. It was enforced by Governor Winfield T. Durbin, who forced investigation into a 1902 lynching and removed the sheriff responsible. In 1903 he sent militia to bring order to a race riot which had broken out on Independence Day in Evansville, Indiana. Durbin also publicly declared that an African American man accused of murder was entitled to a fair trial.

In 1920, 600 men attempted to remove a Black prisoner from Marion County Jail, but were prevented by the city's police.[182][183] Lawrence Beitler photographed the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in 1930 in Marion, Indiana.[184] Seeing this image inspired Abel Meeropol to write the song "Strange Fruit",[185] which was popularized by singer Billie Holiday. In reaction to these murders, Flossie Bailey pushed for passage of the 1931 Indiana anti-lynching law.[186][187] The law provided for the immediate dismissal of any sheriff who allowed a jailed person to be lynched, and allowed the victim's family to sue for $10,000. However, local authorities failed to prosecute mob leaders. In one case when a sheriff was indicted by Indiana's attorney general, James Ogden, the jury refused to convict.[182][183]

Virginia passed anti-lynching legislation, which was signed on March 14, 1928 by Governor Harry F. Byrd following a media campaign by Norfolk Virginian-Pilot editor Louis Isaac Jaffe against mob violence.[188][189]