The Constitution of Japan[b] is the supreme law of Japan. It was written primarily by American civilian officials working under the Allied occupation of Japan after World War II. The current Japanese constitution was promulgated as an amendment of the Meiji Constitution of 1890 on 3 November 1946 when it came into effect on 3 May 1947.[4]

| Constitution of Japan | |

|---|---|

Preamble of the Constitution | |

| Overview | |

| Original title | 日本国憲法 |

| Jurisdiction | Japan |

| Presented | 3 November 1946 |

| Date effective | 3 May 1947 |

| System | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy[1] |

| Government structure | |

| Branches | Three |

| Head of state | None[a] |

| Chambers | Bicameral (National Diet: House of Representatives, House of Councillors) |

| Executive | Cabinet, led by a Prime Minister |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court |

| Federalism | Unitary |

| History | |

| First legislature | |

| First executive | 24 May 1947 |

| First court | 4 August 1947 |

| Amendments | 0[3] |

| Location | National Archives of Japan |

| Author(s) | Milo Rowell, Courtney Whitney, and other US military lawyers working for the US-led Allied GHQ; subsequently reviewed and modified by members of the Imperial Diet |

| Signatories | Emperor Shōwa |

| Supersedes | Meiji Constitution |

| Full text | |

The constitution provides for a parliamentary system of government and guarantees certain fundamental human rights. In contrast to the Meiji Constitution, which invested the Emperor of Japan with supreme political power, under the new constitution the Emperor was reduced to "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people" and exercises only a ceremonial role acting under the sovereignty of the people for constitutional monarchy.[5]

The constitution, also known as the MacArthur Constitution,[6][7] "Post-war Constitution" (戦後憲法, Sengo-Kenpō), or the "Peace Constitution" (平和憲法, Heiwa-Kenpō),[8] was drafted under the supervision of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, during the post-war Allied occupation of Japan.[9] Japanese scholars reviewed and modified it before adoption.[10] It changed Japan's previous system of semi-constitutional monarchy and stratocracy with a parliamentary monarchy. The Constitution is best known for Article 9, by which Japan renounces its right to wage war and maintain military forces.[11] Despite this, Japan retains de facto military capabilities in the form of the Self-Defense Forces and also hosts a substantial American military presence.

The Japanese constitution is the oldest unamended constitution in the world. At roughly 5,000 words it is a relatively short constitution, less than a quarter the length of the average national constitution.[3][12]

Historical origins

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

You can help expand this section with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (June 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Meiji Constitution

editThe Meiji Constitution was the fundamental law of the Empire of Japan, propagated during the reign of Emperor Meiji (r. 1867–1912).[13] It provided for a form of mixed constitutional and absolute monarchy, based on the Prussian and British models. In theory, the Emperor of Japan was the supreme leader, and the cabinet, whose prime minister was elected by a privy council, were his followers; in practice, the Emperor was head of state but the Prime Minister was the actual head of government. Under the Meiji Constitution, the prime minister and his cabinet were not accountable to the elected members of the Imperial Diet, and increasingly deferred to the Imperial Japanese Army in the lead-up to the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The Potsdam Declaration

editOn 26 July 1945, shortly before the end of World War II, Allied leaders of the United States (President Harry S. Truman), the United Kingdom (Prime Minister Winston Churchill), and the Republic of China (President Chiang Kai-shek) issued the Potsdam Declaration. The Declaration demanded Japanese military's unconditional surrender, demilitarisation and democratisation.[14]

The declaration defined the major goals of the post-surrender Allied occupation: "The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established" (Section 10). In addition, "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government" (Section 12). The Allies sought not merely punishment or reparations from a militaristic foe, but fundamental changes in the nature of its political system. In the words of a political scientist Robert E. Ward: "The occupation was perhaps the single most exhaustively planned operation of massive and externally directed political change in world history."

The Japanese government, Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki's administration and Emperor Hirohito accepted the conditions of the Potsdam Declaration, which necessitates amendments to its Constitution after the surrender.[14]

Drafting process

editThe wording of the Potsdam Declaration—"The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles ..."—and the initial post-surrender measures taken by MacArthur, suggest that neither he nor his superiors in Washington intended to impose a new political system on Japan unilaterally. Instead, they wished to encourage Japan's new leaders to initiate democratic reforms on their own. But by early 1946, MacArthur's staff and Japanese officials were at odds over the most fundamental issue, the writing of a new Constitution. Emperor Hirohito, Prime Minister Kijūrō Shidehara, and most of the cabinet members were extremely reluctant to take the drastic step of replacing the 1889 Meiji Constitution with a more liberal document.[15]

Former prime minister Fumimaro Konoe, Shidehara Cabinet and the civil constitutional study groups[16] formed original constitutions. The formal draft constitution, which was created by the Shidehara Cabinet, was rejected by GHQ and the government reviewed the revised drafts by various political parties and accepted liberal ways of thinking especially toward the emperor as the symbol of nationals and dispossession of a military power.

After World War II, the Allied Powers concluded an "Instrument of Surrender" with Japan, which stated that "the Emperor and the Government of Japan shall come under the subordination of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers". Koseki[17] interprets this statement as the GHQ's indirect rule through the Emperor and the Japanese government, rather than direct rule over the Japanese people. In other words, GHQ regarded the Emperor Hirohito not as a war criminal parallel to Hitler and Mussolini but as one governance mechanism.

The Japanese government at the end of World War II was organized by Higashikuni Cabinet (Prime Minister Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni), with Fumimaro Konoe, who had served as the prime minister during the Manchurian Incident in 1931, as a minister without portfolio. The trigger of constitutional amendment was from GHQ General MacArthur's word to Fumimaro Konoe. After an unsuccessful first visit on 13 September 1945, Fumimaro Konoe paid another visit to MacArthur at the GHQ headquarters on 4 October 1945. Although the GHQ later denied this fact, citing a mistake by the Japanese interpreter, diplomatic documents between Japan and the U.S. state that "the Constitution must be amended to fully incorporate liberal elements".[17] "At the meeting, the General told Konoe that the Constitution must be amended".[17] In this regard, it can be said that the GHQ granted Konoe the authority to amend the Constitution. However, at this point, the Higashikuninomiya Cabinet was succeeded by the Shidehara Cabinet, and Jōji Matsumoto, the then Minister of State, stated that the Cabinet should be the only one to amend the Constitution, and the Constitutional Problems Investigation Committee was established. In other words, there was a conflict between the Konoe and Shidehara cabinets as to who should take the initiative in constitutional amendment.

However, this conflict ended with Konoe being nominated as a candidate for Class A war criminal due to domestic and international criticism. To begin with, Konoe was able to have the initiative to amend the Constitution because he had been assigned full-time by the GHQ to amend the constitution, although he was not an unappointed minister when the cabinet was changed. However, due to domestic and foreign criticism of Konoe, the GHQ announced on 1 November that Konoe had not been appointed to amend the Constitution and that he had no authority to lead the amendment of the constitution since the cabinet had changed. At that time, Konoe belonged to the Office of the Minister of the Interior, which was in charge of politics related to the Imperial Household, but since the Office of the Minister of the Interior was about to be abolished, he decided to submit a proposal for amendment before then. Konoe's proposal reflected the wishes of the GHQ and was very liberal in content, including "limitation of the imperial prerogative," "independent dissolution of the Diet," and "freedom of speech," but it was never finally approved as a draft, and Konoe committed suicide by poisoning himself. After this, the authority to amend the Constitution was completely transferred to Shidehara's cabinet.

In late 1945, Shidehara appointed Jōji Matsumoto, state minister without portfolio, head of a blue-ribbon committee of Constitutional scholars to suggest revisions. The Matsumoto Committee was composed of the authorities of the Japanese law academia, including Tatsuki Minobe (美濃部達吉), and the first general meeting was held on 27 October 1945. Jōji Matsumoto presented the following four principles of constitutional amendment[18] to the Budget Committee of the House of Representatives in 1945.

Four principles of constitutional amendment

- Do not change the basic principle of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan that the Emperor has total control.

- To expand the power of the parliament and, as a reflection, limit the matters related to the Emperor's power to some extent.

- Put the responsibility of the Minister of State on all national affairs, and the Minister of State shall be responsible to the Parliament.

- Expand the protection of people's freedoms and rights and take adequate relief measures.

The Matsumoto Committee has prepared a constitutional amendment outline based on these principles.

The Matsumoto Commission's recommendations (ja:松本試案), made public in February 1946, were quite conservative as "no more than a touching-up of the Meiji Constitution".[citation needed] MacArthur rejected them outright and ordered his staff to draft a completely new document. An additional reason for this was that on 24 January 1946, Prime Minister Shidehara had suggested to MacArthur that the new Constitution should contain an article renouncing war.

As the momentum for constitutional amendment increased, interest in the constitution increased among the people. In fact, not only political parties but also private organizations have announced draft constitutional amendments.

The most famous of these is the outline of the draft constitution by the Constitution Study Group. The Constitutional Study Group was established on 29 October 1945 to study and prepare for the establishment of the Constitution from a leftist approach. While many political party drafts only added to the Meiji Constitution, their drafts included the principle of popular sovereignty,[19] which grants sovereignty to the people and regards the Emperor as a symbol of the people. The Constitutional Study Group submitted a draft to the Prime Minister's Office on 26 December 1945. On 2 January 1946, GHQ issued a statement that it would focus on the content. Toyoharu Konishi[20] states that the GHQ may have included the opinion of the Constitutional Study Group in the draft, reflecting the situation in the United States, where people disregarded popular sovereignty at that time. Also, regarding the symbolic emperor system, since the members of the Constitutional Study Group came into contact with the GHQ dignitaries earlier than the drafting of the guidelines, the Constitutional Study Group proposed the symbolic emperor system through the GHQ dignitaries. It is analyzed that it was reflected in the GHQ proposal.

The Constitution was mostly drafted by American authors.[9] A few Japanese scholars reviewed and modified it.[10] Much of the drafting was done by two senior army officers with law degrees: Milo Rowell and Courtney Whitney, although others chosen by MacArthur had a large say in the document. The articles about equality between men and women were written by Beate Sirota.[21][22]

MacArthur gave the authors less than a week to complete the draft, which was presented to surprised Japanese officials on 13 February 1946. MacArthur initially had a policy of not interfering with the revision of the Constitution, but from around January 1946, he made a statement to the Constitutional Draft Outline of the Constitutional Study Group and activated movements related to the Constitution. There are various theories as to the reason. Kenzo Yanagi [23] mentioned the memorandum of Courtney Whitney, who was the director of the Civil Affairs Bureau of the General Headquarters, on 1 February 1946 as a reason for the attitude change. In the memorandum, it is mentioned that the Far Eastern Commission was about to be established. The Far Eastern Commission is the supreme policy-making body established by the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, China, Australia and other allies to occupy and control Japan, and its authority was higher than that of GHQ. MacArthur learned that the Far Eastern Commission was interested in constitutional amendment, and thought that constitutional authority could be transferred to the Far Eastern Commission after the commission was established. Therefore, he might be eager to end the constitutional issue with unlimited authority before it was founded.

On 18 February, the Japanese government called on the GHQ to reconsider the MacArthur Draft, which is significantly different from the Matsumoto Draft, but Whitney rejected the proposal on 20 February. On the contrary, he asked the Japanese government for a reply within 48 hours. Then, Prime Minister Shidehara met with MacArthur on 21 February and decided to accept the MacArthur draft by a cabinet meeting on the following day.

After Shidehara Cabinet decision, Jōji Matsumoto aimed to draft a Japanese government bill based on the MacArthur Draft, and the draft was completed on 2 March of the same year.

On 4 March Jōji Matsumoto presented the draft to Whitney, but GHQ noticed that there were differences between the MacArthur Draft and the 2 March Draft. In particular, the 2 March Draft did not include a preamble, and a heated argument ensued. Finally, adjustments were made by the Japanese government and GHQ, and the draft was completed on 6 March.

On 6 March 1946, the government publicly disclosed an outline of the pending Constitution. On 10 April, elections were held for the House of Representatives of the Ninetieth Imperial Diet, which would consider the proposed Constitution. The election law having been changed, this was the first general election in Japan in which women were permitted to vote.

In the process of passing through the House of Representatives in August 1946, the draft of the Constitutional Amendment was modified. This is called the Ashida Amendment, since the chairman of the committee at the time was Hitoshi Ashida. In particular, Article 9, which refers to the renunciation of armed forces, was controversial.

The phrase "In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph," was added to paragraph 2 by Hitoshi Ashida without the diet deliberations. Although the reason is not clear, this addition has led to the interpretation of the Constitution as allowing the retention of force when factors other than the purpose of the preceding paragraph arise. Even now, there is a great debate over whether force for self-defense, such as the Self Defense Forces, is a violation of the Constitution.

Article 9.

1) Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. 2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Unlike most previous Japanese legal documents, the constitution is written in modern colloquial Japanese instead of Classical Japanese.[24] The Japanese version includes some awkward phrasing and scholars sometimes consult the English drafts to resolve ambiguities.[25][26]

The MacArthur draft, which proposed a unicameral legislature, was changed at the insistence of the Japanese to allow a bicameral one, with both houses being elected. In most other important respects, the government adopted the ideas embodied in 13 February document in its own draft proposal of 6 March. These included the constitution's most distinctive features: the symbolic role of the Emperor, the prominence of guarantees of civil and human rights, and the renunciation of war. The constitution followed closely a 'model copy' prepared by MacArthur's command.[27]

In 1946, criticism of or reference to MacArthur's role in drafting the constitution could be made subject to Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD) censorship (as was any reference to censorship itself).[28] Until late 1947, CCD exerted pre-publication censorship over about 70 daily newspapers, all books, and magazines, and many other publications.[29]

Adoption

editIt was decided that in adopting the new document the Meiji Constitution would not be violated. Rather, to maintain legal continuity, the new Constitution was adopted as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution in accordance with the provisions of Article 73 of that document. Under Article 73, the new constitution was formally submitted to the Imperial Diet, which was elected by universal suffrage, which was also granted to women, in 1946, by the Emperor through an imperial rescript issued on 20 June. The draft constitution was submitted and deliberated upon as the Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution.

The old constitution required that the bill receive the support of a two-thirds majority in both houses of the Diet to become law. Both chambers had made amendments. Without interference by MacArthur, House of Representatives added Article 17, which guarantees the right to sue the State for the tort of officials, Article 40, which guarantees the right to sue the State for wrongful detention, and Article 25, which guarantees the right to life.[30][31] The house also amended Article 9. The House of Peers approved the document on 6 October; the House of Representatives adopted it in the same form the following day, with only five members voting against. It became law when it received the imperial assent on 3 November 1946.[32] Under its own terms, the constitution came into effect on 3 May 1947.

A government organisation, the Kenpō Fukyū Kai ("Constitution Popularisation Society"), was established to promote the acceptance of the new constitution among the populace.[33]

Early proposals for constitutional amendment

editThe new constitution would not have been written the way it was had MacArthur and his staff allowed Japanese politicians and constitutional experts to resolve the issue as they wished.[citation needed] The document's foreign origins have, understandably, been a focus of controversy since Japan recovered its sovereignty in 1952.[citation needed] Yet in late 1945 and 1946, there was much public discussion on constitutional reform, and the MacArthur draft was apparently greatly influenced by the ideas of certain Japanese liberals. The MacArthur draft did not attempt to impose a United States-style presidential or federal system. Instead, the proposed constitution conformed to the British model of parliamentary government, which was seen by the liberals as the most viable alternative to the European absolutism of the Meiji Constitution.[citation needed]

After 1952, conservatives and nationalists attempted to revise the constitution to make it more "Japanese", but these attempts were frustrated for a number of reasons. One was the extreme difficulty of amending it. Amendments require approval by two-thirds of the members of both houses of the National Diet before they can be presented to the people in a referendum (Article 96). Also, opposition parties, occupying more than one-third of the Diet seats, were firm supporters of the constitutional status quo. Even for members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the constitution was advantageous. They had been able to fashion a policy-making process congenial to their interests within its framework. Yasuhiro Nakasone, a strong advocate of constitutional revision during much of his political career, for example, downplayed the issue while serving as prime minister between 1982 and 1987.

Provisions

editThe constitution has a length of approximately 5,000 words and consists of a preamble and 103 articles grouped into 11 chapters. These are:

- I. The Emperor (Articles 1–8)

- II. Renunciation of War (Article 9)

- III. Rights and Duties of the People (Articles 10–40)

- IV. The Diet (Articles 41–64)

- V. The Cabinet (Articles 65–75)

- VI. Judiciary (Articles 76–82)

- VII. Finance (Articles 83–91)

- VIII. Local Self–Government (Articles 92–95)

- IX. Amendments (Article 96)

- X. Supreme Law (Articles 97–99)

- XI. Supplementary Provisions (Articles 100–103)

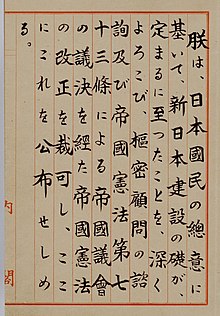

Edict

editThe constitution starts with an imperial edict made by the Emperor. It contains the Emperor's Privy Seal and signature, and is countersigned by the Prime Minister and other Ministers of State as required by the previous constitution of the Empire of Japan. The edict states:

I rejoice that the foundation for the construction of a new Japan has been laid according to the will of the Japanese people, and hereby sanction and promulgate the amendments of the Imperial Japanese Constitution effected following the consultation with the Privy Council and the decision of the Imperial Diet made in accordance with Article 73 of the said Constitution.[32][34]

Preamble

editThe constitution contains a firm declaration of the principle of popular sovereignty in the preamble. This is proclaimed in the name of the "Japanese people" and declares that "sovereign power resides with the people" and that:

Government is a sacred trust of the people, the authority for which is derived from the people, the powers of which are exercised by the representatives of the people, and the benefits of which are enjoyed by the people.

Part of the purpose of this language is to refute the previous constitutional theory that sovereignty resided in the Emperor. The constitution asserts that the Emperor is merely a symbol of the state, and that he derives "his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power" (Article 1). The text of the constitution also asserts the liberal doctrine of fundamental human rights. In particular Article 97 states that:

the fundamental human rights by this Constitution guaranteed to the people of Japan are fruits of the age-old struggle of man to be free; they have survived the many exacting tests for durability and are conferred upon this and future generations in trust, to be held for all time inviolate.

The Emperor (Articles 1–8)

editUnder the constitution, the Emperor is "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people". Sovereignty rests with the people, not the Emperor as it did under the Meiji Constitution.[14] The Emperor carries out most functions of a head of state, formally appointing the Prime Minister and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, convoking the National Diet and dissolving the House of Representatives, and also promulgating statutes and treaties and exercising other enumerated functions. However, he acts under the advice and approval of the Cabinet or the Diet.[14]

In contrast with the Meiji Constitution, the Emperor's role is entirely ceremonial, as he does not have powers related to government. Unlike other constitutional monarchies, he is not even the nominal chief executive or even the nominal commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). The constitution explicitly limits the Emperor's role to matters of state delineated in the constitution. The constitution also states that these duties can be delegated by the Emperor as provided for by law.

Succession to the Chrysanthemum Throne is regulated by the Imperial Household Law and is managed by a ten-member body called the Imperial Household Council. The budget for the maintenance of the Imperial House is managed by resolutions of the Diet.

Renunciation of war (Article 9)

editUnder Article 9, "the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes". To this end, the article provides that "land, sea, and air forces, as well as another war potential, will never be maintained". The necessity and practical extent of Article 9 have been debated in Japan since its enactment, particularly following the establishment of the Japan Self-Defence Forces (JSDF) in 1954, a de facto post-war Japanese military force that substitutes for the pre-war Armed Forces, since 1 July 1954. Some lower courts have found the JSDF unconstitutional, but the Supreme Court never ruled on this issue.[14]

Individuals have also challenged the presence of U.S. forces in Japan as well as the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty under Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan.[35] The Supreme Court of Japan has found that the stationing of U.S. forces did not violate Article 9, because it did not involve forces under Japanese command.[35] The Court ruled the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty to be a highly sensitive political question, and declined to rule on its legality under the political question doctrine.[35]

Various political groups have called for either revising or abolishing the restrictions of Article 9 to permit collective defense efforts and strengthen Japan's military capabilities.[36] On July 1, 2014, the Cabinet of Japan approved a reinterpretation of Article 9 to allow the nation to engage in "collective self-defense."[37]

The United States has pressured Japan to amend Article 9 and to rearm[38][39] as early as 1948[40] with Japan gradually expanding its military capabilities, "sidestepping constitutional constraints".[41]

Individual rights (Articles 10–40)

edit"The rights and duties of the people" are featured prominently in the post-war constitution. Thirty-one of its 103 articles are devoted to describing them in detail, reflecting the commitment to "respect for the fundamental human rights" of the Potsdam Declaration. Although the Meiji Constitution had a section devoted to the "rights and duties of subjects" which guaranteed "liberty of speech, writing, publication, public meetings, and associations", these rights were granted "within the limits of law" and could be limited by legislation.[14] Freedom of religious belief was allowed "insofar as it does not interfere with the duties of subjects" (all Japanese were required to acknowledge the Emperor's divinity, and those, such as Christians, who refused to do so out of religious conviction were accused of lèse-majesté). Such freedoms are delineated in the post-war constitution without qualification.

Individual rights under the Japanese constitution are rooted in Article 13, where the constitution asserts the right of the people "to be respected as individuals" and, subject to "the public welfare", to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness". This article's core notion is jinkaku, which represents "the elements of character and personality that come together to define each person as an individual", and which represents the aspects of each individual's life that the government is obligated to respect in the exercise of its power.[42] Article 13 has been used as the basis to establish constitutional rights to privacy, self-determination and the control of an individual's own image, rights which are not explicitly stated in the constitution.

Subsequent provisions provide for:

- Equality before the law: The constitution guarantees equality before the law and outlaws discrimination against Japanese citizens based on "political, economic or social relations" or "race, creed, sex, social status or family origin" (Article 14). The right to vote cannot be denied on the grounds of "race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income" (Article 44). Equality between the sexes is explicitly guaranteed in relation to marriage (Article 24) and childhood education (Article 26).

- Prohibition of peerage: Article 14 forbids the state from recognising peerage. Honors may be conferred, but they must not be hereditary or grant special privileges.

- Democratic elections: Article 15 provides that "the people have the inalienable right to choose their public officials and to dismiss them". It guarantees universal adult (in Japan, persons age 20 and older) suffrage and the secret ballot.

- Prohibition of slavery: Guaranteed by Article 18. Involuntary servitude is permitted only as punishment for a crime.

- Separation of Religion and State: The state is prohibited from granting privileges or political authority to a religion, or conducting religious education (Article 20).

- Freedom of assembly, association, speech, and secrecy of communications: All guaranteed without qualification by Article 21, which forbids censorship.

- Workers' rights: Work is declared both a right and obligation by Article 27 which also states that "standards for wages, hours, rest and other working conditions shall be fixed by law" and that children shall not be exploited. Workers have the right to participate in a trade union (Article 28).

- Right to property: Guaranteed subject to the "public welfare". The state may take property for public use if it pays just compensation (Article 29). The state also has the right to levy taxes (Article 30).

- Right to due process: Article 31 provides that no one may be punished "except according to procedure established by law". Article 32, which provides that "No person shall be denied the right of access to the courts", originally drafted to recognize criminal due process rights, is now also understood as the source of due process rights for civil and administrative law cases.[43]

- Protection against unlawful detention: Article 33 provides that no one may be apprehended without an arrest warrant, save where caught in flagrante delicto. Article 34 guarantees habeas corpus, right to counsel, and right to be informed of charges. Article 40 enshrines the right to sue the state for wrongful detention.

- Right to a fair trial: Article 37 guarantees the right to a public trial before an impartial tribunal with counsel for one's defence and compulsory access to witnesses.

- Protection against self-incrimination: Article 38 provides that no one may be compelled to testify against themselves, that confessions obtained under duress are not admissible, and that no one may be convicted solely on the basis of their own confession.

- Other guarantees:

- Right to petition government (Article 16)

- Right to sue the state (Article 17)

- Freedom of thought and conscience (Article 19)

- Freedom of expression (Article 19)

- Freedom of religion (Article 20)

- Rights to change residence, choose employment, move abroad and relinquish nationality (Article 22)

- Academic freedom (Article 23)

- Prohibition of forced marriage (Article 24)

- Compulsory education (Article 26)

- Protection against entries, search and seizures (Article 35)

- Prohibition of torture and cruel punishments (Article 36)

- Prohibition of ex post facto laws (Article 39)

- Prohibition of double jeopardy (Article 39)

Under Japanese case law, constitutional human rights apply to corporations to the extent possible given their corporate nature. Constitutional human rights also apply to foreign nationals to the extent that such rights are not by their nature only applicable to citizens (for example, foreigners have no right to enter Japan under Article 22 and no right to vote under Article 15, and their other political rights may be restricted to the extent that they interfere with the state's decision making).

Organs of government (Articles 41–95)

editThe constitution establishes a parliamentary system of government in which legislative authority is vested in a bicameral National Diet. Although a bicameral Diet existed under the existing constitution, the new constitution abolished the upper House of Peers, which consisted of members of the nobility (similar to the British House of Lords). The new constitution provides that both chambers be directly elected, with a lower House of Representatives and an upper House of Councillors.

The Diet nominates the Prime Minister from among its members, although the Lower House has the final authority if the two Houses disagree.[14] Thus, in practice, the Prime Minister is the leader of the majority party of the Lower House.[14] The House of Representatives has the sole ability to pass a vote of no confidence in the Cabinet, can override the House of Councillors' veto on any bill, and has priority in determining the national budget, and approving treaties.

Executive authority is vested in a cabinet, jointly responsible to the Diet, and headed by a Prime Minister.[14] The prime minister and a majority of the cabinet members must be members of the Diet, and have the right and obligation to attend sessions of the Diet. The Cabinet may also advise the Emperor to dissolve the House of Representatives and call for a general election to be held.

The judiciary consists of several lower courts headed by a Supreme Court. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court is nominated by the Cabinet and appointed by the Emperor, while other justices are nominated and appointed by the Cabinet and attested by the Emperor. Lower court judges are nominated by the Supreme Court, appointed by the Cabinet and attested by the Emperor. All courts have the power of judicial review and may interpret the constitution to overrule statutes and other government acts, but only in the event that such interpretation is relevant to an actual dispute.

The constitution also provides a framework for local government, requiring that local entities have elected heads and assemblies, and providing that government acts applicable to particular local areas must be approved by the residents of those areas. These provisions formed the framework of the Local Autonomy Law of 1947, which established the modern system of prefectures, municipalities and other local government entities.

Amendments (Article 96)

editUnder Article 96, amendments to the constitution "shall be initiated by the Diet, through a concurring vote of two-thirds or more of all the members of each House and shall thereupon be submitted to the people for ratification, which shall require the affirmative vote of a majority of all votes cast thereon, at a special referendum or at such election as the Diet shall specify". The constitution has not been amended since its implementation in 1947, although there have been movements led by the Liberal Democratic Party to make various amendments to it.

Other provisions (Articles 97–103)

editArticle 97 provides for the inviolability of fundamental human rights. Article 98 provides that the constitution takes precedence over any "law, ordinance, imperial rescript or other act of government" that offends against its provisions, and that "the treaties concluded by Japan and established laws of nations shall be faithfully observed". In most nations it is for the legislature to determine to what extent, if at all, treaties concluded by the state will be reflected in its domestic law; under Article 98, however, international law and the treaties Japan has ratified automatically form a part of domestic law. Article 99 binds the Emperor and public officials to observe the constitution.

The final four articles set forth a six-month transitional period between adoption and implementation of the Constitution. This transitional period took place from 3 November 1946, to 3 May 1947. Pursuant to Article 100, the first House of Councillors election was held during this period in April 1947, and pursuant to Article 102, half of the elected Councillors were given three-year terms. A general election was also held during this period, as a result of which several former House of Peers members moved to the House of Representatives. Article 103 provided that public officials currently in office would not be removed as a direct result of the adoption or implementation of the new Constitution.

Amendments and revisions

editConstitutional reform in Japan, colloquially known as Kaiken-ron (改憲論), is an ongoing political effort to reform the Constitution of Japan.

The effort recently gained traction in the 2010s as the Japanese government under then-prime minister Shinzo Abe attempted to revise Article 9 of the Constitution, which prohibits Japan from waging war as means to settle international disputes, as well as prohibiting Japan from having an armed forces with war potential.[44][45] Although Abe's attempt was unsuccessful due to his leaving office in 2020 and his subsequent assassination, incumbent prime minister Fumio Kishida has said that he is "determined" to work on constitutional reform, citing the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, recent tensions in Taiwan, and North Korea's development of weapons of mass destruction as his basis.[46]See also

editFormer constitutions

edit- Seventeen-article constitution (604) - rather a document of moral teachings, not a constitution in the modern meaning.

- Meiji Constitution (1889)

Others

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Kristof, Nicholas D. (12 November 1995). "Japan's State Symbols: Now You See Them ..." The New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Kakinohana, Hōjun (23 September 2013). 個人の尊厳は憲法の基一天皇の元首化は時代に逆行一. Japan Institute of Constitutional Law (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ a b "The Anomalous Life of the Japanese Constitution". Nippon.com. 15 August 2017. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ Goes into Effect, New Japanese Constitution. "May 3, 1947, New Japanese Constitution goes into effect". www.history.com. History.com Editors. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Takemae 2002, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Kawai, Kazuo (1958). "The Divinity of the Japanese Emperor". Political Science. 10 (2): 3–14. doi:10.1177/003231875801000201.

- ^ "The American Occupation of Japan, 1945-1952". Columbia University.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 11.

- ^ a b Moritsugu, Ken (18 August 2016). "Biden's remark on Japan Constitution raises eyebrows". AP News. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 9.

- ^ Ito, Masami, "Constitution again faces calls for revision to meet reality Archived 8 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 1 May 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Constitution, Meiji. "The Meiji Constitution". www.britannica.com. The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica History. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Oda, Hiroshi (2009). "Sources of Law". Japanese Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199232185.001.1. ISBN 978-0-19-923218-5.

- ^ John Dower, Embracing Defeat, 1999, pp. 374, 375, 383, 384.

- ^ Koseki, Shoichi (2017). Nihonkokukenpo no Tanjo (日本国憲法の誕生). Iwanami Bunko(岩波文庫). pp. 37–57.

- ^ a b c Shoichi, Koseki (2017). Nihonkokukenpo no Tanjo (日本国憲法の誕生). Iwanami Bunko(岩波文庫). pp. 14 & 15.

- ^ Joji, Matsumoto (1945). Kempo Kaisei Yon Gensoku.

- ^ "Documents with Commentaries Part 2 Creation of Various Proposals to Reform the Constitution/2-16 Constitution Investigation Association, "Outline of Constitution Draft," December 26, 1945". National Diet Library. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Toyoharu, Konishi (2006). Kempo Oshitsukeron no "Maboroshi". Kodansha Gendai Shinsho.

- ^ Dower, John W. (1999). Embracing defeat: Japan in the wake of World War II (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Co/New Press. pp. 365–367. ISBN 978-0393046861.

- ^ "Beate Gordon, a drafter of Japan's Constitution, dies at 89". The Mainichi. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Kenzo, Yanagi (1972). Nihonkoku Kempo Seitei no Katei: Rengokoku Soushireibu gawa no Kirokuni Yoru I. Yuikaku. p. 79.

- ^ Inoue, Kyoko (1991). MacArthur's Japanese Constitution. University of Chicago Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-226-38391-0.

- ^ Inoue, Kyoko (1 January 1987). "Democracy in the ambiguities of two languages and cultures: the birth of a Japanese constitution". Linguistics. 25 (3): 595–606. doi:10.1515/ling.1987.25.3.595. ISSN 1613-396X. S2CID 144432801.

- ^ "Looking back in Yearning". The Economist. Vol. 186. 8 March 1958. p. 14.

- ^ Takemae 2002, p. xxxvii.

- ^ John Dower, Embracing Defeat, p.411: "categories of deletions and suppressions" in CCD's key log in June 1946.

- ^ Dower, p. 407

- ^ Hideki SHIBUTANI(渋谷秀樹)(2013) Japanese Constitutional Law. 2nd ed.(憲法 第2版) p487 Yuhikaku Publishing(有斐閣)

- ^ "衆憲資第90号「日本国憲法の制定過程」に関する資料" (PDF). Commission on the Constitution, The House of Representatives, Japan. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Text of the Constitution and Other Important Documents". National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Publication and Work of the Constitution Popularization Society". Birth of the Constitution of Japan. National Diet Library of Japan. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "日本国憲法". National Archives of Japan. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Chen, Po Liang; Wada, Jordan T. (2017). "Can the Japanese Supreme Court Overcome the Political Question Hurdle?". Washington International Law Journal. 26: 349–79.

- ^ Calls for revision, Japan LDP Chief (10 July 2016). "Japan's LDP Chief Calls for Revision of Article 9 Pacifist Rule". Reuters. Reuters Staff. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "A Primer on Japan's Constitutional Reinterpretation and Right to Collective Self-Defense". Default. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ "Article 9 and the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Takenaka, Linda Sieg, Kiyoshi (1 July 2014). "Japan takes historic step from post-war pacifism, OKs fighting for allies". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Umeda, Sayuri (September 2015). "Japan: Interpretations of Article 9 of the Constitution". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Kingston, Jeff (11 November 2020). "Japan's quiet rearmament". Prospect Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Levin, Mark (2001). "Essential Commodities and Racial Justice: Using Constitutional Protection of Japan's Indigenous Ainu People to Inform Understandings of the United States and Japan". New York University of International Law and Politics. 33. Rochester, NY: 419. SSRN 1635451.

- ^ Levin, Mark (5 August 2010). "Civil Justice and the Constitution: Limits on Instrumental Judicial Administration in Japan". Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal. 20 (2). Rochester, NY: 265–318. SSRN 1653992.

- ^ "The case against Abe's constitutional amendment | East Asia Forum". 5 April 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Japan's Article 9: Pacifism and protests as defence budget doubles | Lowy Institute". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Ninivaggi, Gabriele (30 January 2024). "Kishida comes full circle in policy speech with emphasis on 'power'". The Japan Times. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

Sources

edit- The Constitution of Japan Project 2004. Rethinking the Constitution: An Anthology of Japanese Opinion. Trans. by F. Uleman. Kawasaki, Japan: Japan Research Inc., 2008. ISBN 1-4196-4165-4.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674984424.

- Kishimoto, Koichi. Politics in Modern Japan. Tokyo: Japan Echo, 1988. ISBN 4-915226-01-8. Pages 7–21.

- Matsui, Shigenori. The Constitution of Japan: A Contextual Analysis. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84113-792-6.

- Hook, Glenn D., ed. (2005). Contested governance in Japan : sites and issues. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0415364980.

- Moore, Ray A.; Robinson, Donald L. (2004). Partners for democracy : crafting the new Japanese state under MacArthur. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195171761.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Takemae, Eiji (2002). Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy. Translated by Ricketts, Robert; Swann, Sebastian. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0826462472.

- "Special Issue Constitutional Law in Japan and the United Kingdom". King's Law Journal. 2 (2). 2015.

- This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Japan: A Country Study. Federal Research Division.

External links

edit- Constitution of Japan at Project Gutenberg

- The Constitution of Japan public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Birth of the Constitution of Japan

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Judicial Decisions for 2004, trans. Daryl Takeno, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Legal Precedents for 2005, trans. John Donovan, Yuko Funaki, and Jennifer Shimada, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Legal Precedents for 2006, trans. Asami Miyazawa and Angela Thompson, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Legal Precedents for 2007, trans. Mark A. Levin and Jesse Smith, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Library of Congress Country Study on Japan

- Beate Sirota Gordon (Blog about Beate Sirota Gordon and the documentary film "The Gift from Beate")

- Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University

- 新憲法草案 (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party's Center to Promote Enactment of a New Constitution website (in Japanese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2006. Shin Kenpou Sou-an, Draft New Constitution. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party on 22 November 2005.

- 新憲法制定推進本部. Liberal Democratic Party website (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 10 January 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2006. Web page of the Shin Kenpou Seitei Suishin Honbu, Center to Promote Enactment of a New Constitution, of the Liberal Democratic Party.

- 日本国憲法改正草案 (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party (in Japanese). Retrieved 27 December 2012. Nihon-koku Kenpou Kaisei Souan, Amendment Draft of the Constitution of Japan. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party on 27 April 2012.

- 日本国憲法改正草案Q&A (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party (in Japanese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2012. Nihon-koku Kenpou Kaisei Souan Q & A. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party in October 2012.