David Warren Brubeck (/ˈbruːbɛk/; December 6, 1920 – December 5, 2012) was an American jazz pianist and composer. Often regarded as a foremost exponent of cool jazz, Brubeck's work is characterized by unusual time signatures and superimposing contrasting rhythms, meters, tonalities, and combining different styles and genres, like classic, jazz, and blues.

Dave Brubeck | |

|---|---|

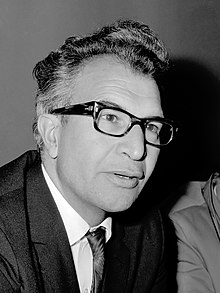

Brubeck at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol in 1964 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | David Warren Brubeck |

| Born | December 6, 1920 Concord, California, U.S. |

| Died | December 5, 2012 (aged 91) Norwalk, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument | Piano |

| Discography | Dave Brubeck discography |

| Years active | 1940s–2012 |

| Labels | |

| Website | davebrubeck |

Born in Concord, California, Brubeck was drafted into the US Army, but was spared from combat service when a Red Cross show he had played at became a hit. Within the US Army, Brubeck formed one of the first racially diverse bands. In 1951, Brubeck formed the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which kept its name despite shifting personnel. The most successful—and prolific—lineup of the quartet was the one between 1958 and 1968. This lineup, in addition to Brubeck, featured saxophonist Paul Desmond, bassist Eugene Wright and drummer Joe Morello. A U.S. Department of State-sponsored tour in 1958 featuring the band inspired several of Brubeck's subsequent albums, most notably the 1959 album Time Out. Despite its esoteric theme and contrarian time signatures, Time Out became Brubeck's highest-selling album, and the first jazz album to sell over one million copies. The lead single from the album, "Take Five", a tune written by Desmond in 5

4 time, similarly became the highest-selling jazz single of all time.[1][2][3] The quartet followed up Time Out with four other albums in non-standard time signatures, and some of the other songs from this series became hits as well, including "Blue Rondo à la Turk" (in 9

8) and "Unsquare Dance" (in 7

4). Brubeck continued releasing music until his death in 2012.

Brubeck's style ranged from refined to bombastic, reflecting both his mother's classical training and his own improvisational skills. He expressed elements of atonality and fugue. Brubeck, with Desmond, used elements of West Coast jazz near the height of its popularity, combining them with the unorthodox time signatures seen in Time Out. Like many of his contemporaries, Brubeck played into the style of the French composer Darius Milhaud, especially his earlier works, including "Serenade Suite" and "Playland-At-The-Beach". Brubeck's fusion of classical music and jazz would come to be known as "third stream", although Brubeck's use of third stream would predate the coining of the term. John Fordham of The Guardian commented: "Brubeck's real achievement was to blend European compositional ideas, very demanding rhythmic structures, jazz song-forms and improvisation in expressive and accessible ways."[4]

Brubeck was the recipient of several music awards and honors throughout his lifetime. In 1996, Brubeck received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2008, Brubeck was inducted into the California Hall of Fame, and a year later, he was given an honorary Doctor of Music degree from Berklee College of Music. Brubeck's 1959 album Time Out was added to the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry in 2005. Noted as "one of Jazz's first pop stars" by the Los Angeles Times, Brubeck rejected his fame, and felt uncomfortable with Time magazine featuring him on the cover before Duke Ellington.[5]

Ancestry and early life

editBrubeck had paternal Swiss ancestry (the family surname was originally Brodbeck),[6] and his maternal grandparents were English and German.[7][8][9] He was born on December 6, 1920, in Concord, California,[1] and grew up in the rural town of Ione, California. His father, Peter Howard "Pete" Brubeck, was a cattle rancher. His mother, Elizabeth (née Ivey), had studied piano in England under Myra Hess and intended to become a concert pianist. She taught piano for extra money.[10]

Brubeck did not intend to become a musician, although his two older brothers, Henry and Howard, were already on that track. Brubeck did, however, take lessons from his mother. He could not read music during these early lessons, attributing the difficulty to poor eyesight, but "faked" his way through well enough that his deficiency went mostly unnoticed.[11]

Planning to work with his father on their ranch, Brubeck entered the liberal arts college College of the Pacific in Stockton, California, in 1938 to study veterinary science. He switched his major to music at the urging of the head of zoology at the time, Dr. Arnold, who told him, "Brubeck, your mind's not here. It's across the lawn in the conservatory. Please go there. Stop wasting my time and yours."[12] Later, Brubeck was nearly expelled when one of his music professors discovered that he was unable to sight-read. Several others came forward to his defense, however, arguing that his ability to write counterpoint and harmony more than compensated, and demonstrated his skill with music notation. The college was still concerned, but agreed to allow Brubeck to graduate after he promised never to teach piano.[13]

Military service

editAfter graduating in 1942, Brubeck was drafted into the United States Army, serving in Europe in the Third Army under George S. Patton. He volunteered to play piano at a Red Cross show; the show was a resounding success, and Brubeck was spared from combat service. He created one of the U.S. armed forces' first racially integrated bands, "The Wolfpack".[13] It was in the military, in 1944, that Brubeck met Paul Desmond.[14]

After serving nearly four years in the army, he returned to California for graduate study at Mills College in Oakland. He was a student of composer Darius Milhaud, who encouraged him to study fugue and orchestration, but not classical piano. While on active duty, he had received two lessons from Arnold Schoenberg at UCLA in an attempt to connect with high modernist theory and practice.[15] However, the encounter did not end on good terms since Schoenberg believed that every note should be accounted for, an approach which Brubeck could not accept.

But, according to his son Chris Brubeck, there is a twelve-tone row in The Light in the Wilderness, Dave Brubeck's first oratorio. In it, Jesus's Twelve Disciples are introduced, each singing their own individual notes; it is described as "quite dramatic, especially when Judas starts singing 'Repent' on a high and straining dissonant note".[16]

Jack Sheedy owned San Francisco-based Coronet Records, which had previously recorded area Dixieland bands. (This Coronet Records is distinct from the late 1950s New York-based budget label, and also from Australia-based Coronet Records.) In 1949, Sheedy was convinced to make the first recording of Brubeck's octet and later his trio. But Sheedy was unable to pay his bills and in 1949 gave up his masters to his record stamping company, the Circle Record Company, owned by Max and Sol Weiss. The Weiss brothers soon changed the name of their business to Fantasy Records.

The first Brubeck records sold well, and he made new records for Fantasy. Soon the company was shipping 40,000 to 50,000 copies of Brubeck records each quarter, making a good profit.[17]

Career

editDave Brubeck Quartet

editIn 1951, Brubeck organized the Dave Brubeck Quartet, with Paul Desmond on alto saxophone. The two took up residency at San Francisco's Black Hawk nightclub and had success touring college campuses, recording a series of live albums.

The first of these live albums, Jazz at Oberlin, was recorded in March 1953 in the Finney Chapel at Oberlin College. Brubeck's live performance was credited with legitimizing the field of jazz music at Oberlin, and the album is one of the earliest examples of cool jazz.[18][19] Brubeck returned to College of the Pacific to record Jazz at the College of the Pacific in December of that year.

Following the release of Jazz at the College of the Pacific, Brubeck signed with Fantasy Records, believing that he had a stake in the company. He worked as an artists and repertoire promoter for the label, encouraging the Weiss brothers to sign other contemporary jazz performers, including Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker and Red Norvo. Upon discovering that the deal was for a half interest in his own recordings, Brubeck quit to sign with another label, Columbia Records.[20]

College success

editIn June 1954, Brubeck released Jazz Goes to College, with double bassist Bob Bates and drummer Joe Dodge. The album is a compilation of the quartet's visits to three colleges: Oberlin College, University of Michigan, and University of Cincinnati, and features seven songs, two of which were written by Brubeck and Desmond. "Balcony Rock", the opening song on the album, was noted for its timing and uneven tonalities, themes that would be explored by Brubeck later.[21]

Brubeck was featured on the cover of Time in November 1954, the second jazz musician to be featured, following Louis Armstrong in February 1949.[22] Brubeck personally found this acclaim embarrassing, since he considered Duke Ellington more deserving and was convinced that he had been favored as a white man.[23] In one encounter with Ellington, he knocked on the door of Brubeck's hotel room to show him the cover; Brubeck's response was, "It should have been you."[24]

Early bassists for the group included Ron Crotty, Bates, and Bates's brother Norman; Lloyd Davis and Dodge held the drum chair. In 1956, Brubeck hired drummer Joe Morello, who had been working with pianist Marian McPartland; Morello's presence made possible the rhythmic experiments that were to come.

In 1958, African-American bassist Eugene Wright joined for the group's Department of State tour of Europe and Asia.[25] The group visited Poland, Turkey, India, Ceylon, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq on behalf of the Department of State. They spent two weeks in Poland, giving thirteen concerts and visiting with Polish musicians and citizens as part of the People-to-People program.[26] Wright became a permanent member in 1959, finishing the "classic era" of the quartet's personnel. During this time, Brubeck was strongly supportive of Wright's inclusion in the band, and reportedly canceled several concerts when the club owners or hall managers objected to presenting an integrated band. He also canceled a television appearance when he found out that the producers intended to keep Wright off-camera.[27]

Time Out

editIn 1959, the Dave Brubeck Quartet recorded Time Out. The album, which featured pieces entirely written by members of the quartet, notably uses unusual time signatures in the field of music—and especially jazz—a crux which Columbia Records was enthusiastic about, but which they were nonetheless hesitant to release.[28]

The release of Time Out required the cooperation of Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson, who underwrote and released Time Out, on the condition that the quartet record a conventional album of the American South, Gone with the Wind, to cover the risk of Time Out becoming a commercial failure.[28]

Featuring the cover art of S. Neil Fujita, Time Out was released in December 1959, to negative critical reception.[29] Nonetheless, on the strength of these unusual time signatures, the album quickly went Gold (and was eventually certified Double Platinum), and peaked at number two on the Billboard 200. It was the first jazz album to sell more than a million copies.[30] The single "Take Five" off the album quickly became a jazz standard, despite its unusual composition and its time signature: 5

4 time.

Time Out was followed by several albums with a similar approach, including Time Further Out: Miro Reflections (1961), using more 5

4, 6

4, and 9

8, plus the first attempt at 7

4; Countdown—Time in Outer Space (dedicated to John Glenn, 1962), featuring 11

4 and more 7

4; Time Changes (1963), with much 3

4, 10

4 and 13

4; and Time In (1966). These albums (except Time In) were also known for using contemporary paintings as cover art, featuring the work of Joan Miró on Time Further Out, Franz Kline on Time in Outer Space, and Sam Francis on Time Changes.

Later work

editOn a handful of albums in the early 1960s, clarinetist Bill Smith replaced Desmond. These albums were devoted to Smith's compositions and thus had a somewhat different aesthetic than other Brubeck Quartet albums. Nonetheless, according to critic Ken Dryden, "[Smith] proves himself very much in Desmond's league with his witty solos".[31] Smith was an old friend of Brubeck's; they would record together, intermittently, from the 1940s until the final years of Brubeck's career.

In 1961, Brubeck and his wife, Iola, developed a jazz musical, The Real Ambassadors, based in part on experiences they and their colleagues had during foreign tours on behalf of the Department of State. The soundtrack album, which featured Louis Armstrong, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, and Carmen McRae was recorded in 1961; the musical was performed at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival.

At its peak in the early 1960s, the Brubeck Quartet was releasing as many as four albums a year. Apart from the "College" and the "Time" series, Brubeck recorded four LP records featuring his compositions based on the group's travels, and the local music they encountered. Jazz Impressions of the U.S.A. (1956, Morello's debut with the group), Jazz Impressions of Eurasia (1958), Jazz Impressions of Japan (1964), and Jazz Impressions of New York (1964) are less well-known albums, but they produced Brubeck standards such as "Summer Song", "Brandenburg Gate", "Koto Song", and "Theme from Mr. Broadway". (Brubeck wrote, and the Quartet performed, the theme song for this Craig Stevens CBS drama series; the music from the series became material for the New York album.)

In 1961, Brubeck appeared in a few scenes of the British jazz/beat film All Night Long, which starred Patrick McGoohan and Richard Attenborough. Brubeck plays himself, with the film featuring close-ups of his piano fingerings. Brubeck performs "It's a Raggy Waltz" from the Time Further Out album and duets briefly with bassist Charles Mingus in "Non-Sectarian Blues".

Brubeck also served as the program director of WJZZ-FM (now WEZN-FM) while recording for the quartet. He achieved his vision of an all-jazz format radio station along with his friend and neighbor John E. Metts, one of the first African Americans in senior radio management.

The final studio album for Columbia by the Desmond/Wright/Morello quartet was Anything Goes (1966), featuring the songs of Cole Porter. A few concert recordings followed, and The Last Time We Saw Paris (1967) was the "Classic" quartet's swan-song.

Later career

editBrubeck produced The Gates of Justice in 1968, a cantata mixing Biblical scripture with the words of Martin Luther King Jr. In 1971, the new senior management at Columbia Records decided not to renew Brubeck's contract, as they wished to focus on rock music. He moved to Atlantic Records.[32]

Brubeck's music was used in the 1985 film Ordeal by Innocence. He also composed for—and performed with his ensemble on—"The NASA Space Station", a 1988 episode of the CBS TV series This Is America, Charlie Brown.[33]

Personal life

editBrubeck founded the Brubeck Institute in 2000 with his wife, Iola, at their alma mater, the University of the Pacific. What began as a special archive, consisting of the personal document collection of the Brubecks, has since expanded to provide fellowships and educational opportunities in jazz for students. One of the main streets on which the school resides is named in his honor, Dave Brubeck Way.[34]

In 2008, Brubeck became a supporter of the Jazz Foundation of America in its mission to save the homes and the lives of elderly jazz and blues musicians, including those who had survived Hurricane Katrina.[35] Brubeck supported the Jazz Foundation by performing in its annual benefit concert "A Great Night in Harlem".[36]

Family

editDave Brubeck married jazz lyricist Iola Whitlock in September 1942; the couple were married for 70 years, until his death in 2012. Iola died at age 90 on March 12, 2014, from cancer in Wilton, Connecticut.[37][38]

Brubeck had six children with Iola, including a daughter Catherine. Four of their sons became professional musicians. The eldest, Darius, named after Brubeck's mentor Darius Milhaud, is a pianist, producer, educator and performer.[39] Dan is a percussionist, Chris is a multi-instrumentalist and composer, and Matthew, the youngest, is a cellist, with an extensive list of composing and performance credits. Another son, Michael, died in 2009.[40][41] Brubeck's children often joined him in concerts and in the recording studio.

Religion

editBrubeck became a Catholic in 1980, shortly after completing the Mass To Hope, which had been commissioned by Ed Murray, editor of the national Catholic weekly Our Sunday Visitor. Although he had spiritual interests before that time, he said, "I didn't convert to Catholicism, because I wasn't anything to convert from. I just joined the Catholic Church."[42]

Honors

editIn 1996, he received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2006, Brubeck was awarded the University of Notre Dame's Laetare Medal, the oldest and most prestigious[43] honor given to American Catholics, during the university's commencement. He performed "Travellin' Blues" for the graduating class of 2006.

Death

editBrubeck died of heart failure on December 5, 2012, in Norwalk, Connecticut, one day before his 92nd birthday. He was on his way to a cardiology appointment, accompanied by his son Darius.[44] A birthday party concert had been planned for him with family and famous guests.[45] A memorial tribute was held in May 2013.[46]

Brubeck is interred at Umpawaug Cemetery in Redding, Connecticut.[47][48]

Legacy

editThe Los Angeles Times noted that he "was one of Jazz's first pop stars", even though he was not always happy with his fame. He felt uncomfortable, for example, that Time magazine had featured him on the cover[49] before it did so for Duke Ellington, saying, "It just bothered me."[5] The New York Times noted he had continued to play well into his old age, performing in 2011 and in 2010 only a month after getting a pacemaker, with Times music writer Nate Chinen commenting that Brubeck had replaced "the old hammer-and-anvil attack with something almost airy" and that his playing at the Blue Note Jazz Club in New York City was "the picture of judicious clarity".[41]

In The Daily Telegraph, music journalist Ivan Hewett wrote: "Brubeck didn't have the réclame of some jazz musicians who lead tragic lives. He didn't do drugs or drink. What he had was endless curiosity combined with stubbornness", adding: "His work list is astonishing, including oratorios, musicals and concertos, as well as hundreds of jazz compositions. This quiet man of jazz was truly a marvel."[50]

In The Guardian, John Fordham said "Brubeck's real achievement was to blend European compositional ideas, very demanding rhythmic structures, jazz song-forms and improvisation in expressive and accessible ways. His son Chris told The Guardian "when I hear Chorale, it reminds me of the very best Aaron Copland, something like Appalachian Spring. There's a sort of American honesty to it."[4] Robert Christgau dubbed Brubeck the "jazz hero of the rock and roll generation".[51]

The Economist wrote: "Above all they found it hard to believe that the most successful jazz in America was being played by a family man, a laid-back Californian, modest, gentle and open, who would happily have been a rancher all his days—except that he couldn't live without performing, because the rhythm of jazz, under all his extrapolation and exploration, was, he had discovered, the rhythm of his heart."[52]

While on tour performing "Hot House" in Toronto, Chick Corea and Gary Burton completed a tribute to Brubeck on the day of his death. Corea played "Strange Meadow Lark", from Brubeck's album Time Out.[53]

In the United States, May 4 is informally observed as "Dave Brubeck Day". In the format most commonly used in the U.S., May 4 is written "5/4", recalling the time signature of "Take Five", Brubeck's best-known recording.[54] In September 2019, musicologist Stephen A. Crist's book, Dave Brubeck's Time Out, provided the first scholarly book length analysis of the seminal album. In addition to his musical analyses of each of the album's original compositions, Crist provides insight into Brubeck's career during a time he was rising to the top of the jazz charts.[55]

Recognition

editIn 1975, the main-belt asteroid 5079 Brubeck was named after Brubeck.[56]

Brubeck recorded five of the seven tracks of his album Jazz Goes to College in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He returned to Michigan many times, including a performance at Hill Auditorium where he received a Distinguished Artist Award from the University of Michigan's Musical Society in 2006. Brubeck was presented with a "Benjamin Franklin Award for Public Diplomacy" by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2008 for offering an American "vision of hope, opportunity and freedom" through his music.[57] "As a little girl I grew up on the sounds of Dave Brubeck because my dad was your biggest fan", said Rice.[58] The State Department said in a statement that "as a pianist, composer, cultural emissary and educator, Dave Brubeck's life's work exemplifies the best of America's cultural diplomacy".[57] At the ceremony, Brubeck played a brief recital for the audience at the State Department.[57] "I want to thank all of you because this honor is something that I never expected. Now I am going to play a cold piano with cold hands", Brubeck stated.[57]

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver announced on May 28, 2008, that Brubeck would be inducted into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts. The induction ceremony occurred December 10, and he was inducted alongside eleven other famous Californians.[59]

On October 18, 2008, Brubeck received an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the prestigious Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Similarly, at the Monterey Jazz Festival in September 2009, Brubeck was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree (D.Mus. honoris causa) from Berklee College of Music.[60] On May 16, 2010, Brubeck was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree (honoris causa) from the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. The ceremony took place on the National Mall.[61]

In September 2009, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts announced Brubeck as a Kennedy Center Honoree for exhibiting excellence in performance arts.[62] The Kennedy Center Honors Gala took place on Sunday, December 6 (Brubeck's 89th birthday), and was broadcast nationwide on CBS on December 29 at 9:00 pm EST. When the award was made, President Barack Obama recalled a 1971 concert Brubeck had given in Honolulu and said, "You can't understand America without understanding jazz, and you can't understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck."[40]

On July 5, 2010, Brubeck was awarded the Miles Davis Award at the Montreal International Jazz Festival.[63] In 2010, Bruce Ricker and Clint Eastwood produced Dave Brubeck: In His Own Sweet Way, a documentary about Brubeck for Turner Classic Movies (TCM) to commemorate his 90th birthday in December 2010.[64]

The Concord Boulevard Park in his hometown of Concord, California, was posthumously renamed to "Dave Brubeck Memorial Park" in his honor. Mayor Dan Helix favorably recalled one of his performances at the park, saying: "He will be with us forever because his music will never die."[65]

Awards

edit- Connecticut Arts Award (1987)

- National Medal of Arts, National Endowment for the Arts (1994)

- DownBeat Hall of Fame (1994)

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1996)

- Doctor of Sacred Theology, Doctorate honoris causa, University of Fribourg, Switzerland (2004)[66]

- Laetare Medal (University of Notre Dame) (2006)

- BBC Jazz Lifetime Achievement Award (2007)

- Benjamin Franklin Award for Public Diplomacy (2008)[57]

- Inducted into California Hall of Fame (2008)

- Eastman School of Music Honorary Degree (2008)[67]

- Kennedy Center Honors (2009)[68]

- George Washington University Honorary Degree (2010)[69]

- Honorary Fellow of Westminster Choir College, Princeton, New Jersey (2011)

Discography

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Reception honors Concord native son, jazz great Dave Brubeck". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2007., ci.concord.ca.us. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- ^ "Jazz Music – Jazz Artists – Jazz News". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Russonello, Giovanni (December 7, 2020). "'Take Five' Is Impeccable. 'Time Outtakes' Shows How Dave Brubeck Made It. - An album of previously unheard recordings from the "Time Out" sessions in 1959 reveals the making of a masterpiece". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Fordham, John (December 5, 2012). "Dave Brubeck obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Brown, August (December 5, 2012). "Jazz great Dave Brubeck dies at 91". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ "The Second Oldest Profession? (Part 4)" by Ratzo B. Harris, NewMusicBox, December 21, 2012

- ^ "Ancestry of Dave Brubeck". Wargs.com. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ and possibly Native American Modoc Tribe – see: paragraph one, of the second page of the Dave Brubeck interview by Martin Totusek in Cadence Magazine – The Review of Jazz & Blues, December 1994, Vol. 20 No. 12, pp. 5–17

- ^ "Dave Brubeck NEA Jazz Master (1999)" (PDF). Smithsonianjazz.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Storb, Ilse (2000). Jazz meets the world – the world meets Jazz, Volume 4 of Populäre Musik und Jazz in der Forschung. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 129. ISBN 3-8258-3748-3.

- ^ Fishko, Sara. "An Hour With Dave Brubeck". WNYC. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ It's About Time: The Dave Brubeck Story, by Fred M. Hall.

- ^ a b "Rediscovering Dave Brubeck | The Man | With Hedrick Smith". PBS. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Liner notes to the album 25th Anniversary Reunion, Dave Brubeck Quartet

- ^ Starr, Kevin. 2009. Golden dreams: California in an age of abundance, 1950–1963. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Brubeck, Chris (December 19, 2012). "My Mentor, My Collaborator, My Father: Dave Brubeck". Newmusicbox.org. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Gioia, Ted. "Dave Brubeck and Modern Jazz in San Francisco" in West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California 1945–1960, University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., 1998 (reprint of 1962 edition), pp. 63–64.

- ^ "Legendary Brubeck Album Jazz at Oberlin was Recorded Fifty Years Ago—March 2, 1953". March 2, 2003. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Fordham, John (January 11, 2010). "50 great moments in jazz: Dave Brubeck's Jazz at Oberlin". The Guardian. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "The San Francisco Scene in the 1950s", West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California 1945–1960, Ted Gioia, University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., 1998 (reprint of 1962 edition), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Planer, Lindsay. "Jazz Goes to College - The Dave Brubeck Quartet". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ Time magazine cover: Louis Armstrong – February 21, 1949

- ^ Kaplan, Fred (2009). 1959: The Year that Changed Everything. John Wiley & Songs. p. 131.

- ^ "Sample Liner Notes by Darius Brubeck". Dave Brubeck Live in '64 & '66. 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ Schudel, Matt (April 6, 2008). "Ambassador of Cool". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ Hatschek, Keith (December 1, 2010). "The Impact of American Jazz Diplomacy in Poland During the Cold War Era". Jazz Perspectives. 4 (3): 253–300. doi:10.1080/17494060.2010.561088. ISSN 1749-4060. S2CID 154745124.

- ^ Grabar, Henry (December 5, 2012). "How Dave Brubeck Used His Talents to Fight for Integration". The Atlantic Cities. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ a b Kaplan (2009). 1959. J. Wiley & Sons. pp. 131–132. ISBN 9780470387818.

- ^ Brubeck, Dave (November 1996). Time Out is still in (Media notes). Sony Music Entertainment.

- ^ Chilton, Martin (December 5, 2012), "Dave Brubeck, Take Five jazz star, dies 91", The Daily Telegraph, retrieved December 5, 2012

- ^ "Near-Myth – The Dave Brubeck Quartet | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic". allmusic.com. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Fred M. (1996). It's About Time. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 1-55728-404-0.

- ^ Minovitz, Ethan (December 11, 2012). "Take Five Jazz Great Dave Brubeck Dead at 91". Big Cartoon DataBase. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Brubeck Summer Jazz Colony". Web.pacific.edu. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "Dave Brubeck, Hank Jones and Norah Jones Perform at Jazz Foundation of America's "A Great Night in Harlem" Benefit on May 29th". Allaboutjazz.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "J.B. Spins: JFA Delivers Another Great Night". Jbspins.blogspot.com. May 30, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Iola Brubeck dies Archived December 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, recordnet.com; accessed March 14, 2014.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (September 10, 2009). Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance 1950–1963. Oxford University Press. pp. 393–. ISBN 978-0-19-515377-4. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Darius Brubeck – Piano". Rediscovering Dave Brubeck. PBS. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Dave Brubeck, worldwide ambassador of jazz, dies at 91". washingtonpost.com. December 6, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Ratliff, Ben (December 6, 1920). "Dave Brubeck, Jazz Musician, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Rediscovering Dave Brubeck, PBS

- ^ "Jazz legend Dave Brubeck to receive Laetare Medal". University of Notre Dame Office of News & Information. March 25, 2006. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- ^ "Jazz pianist Dave Brubeck dead at age 91". Chicago Tribune. December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "Jazz great Dave Brubeck dies in Connecticut". USA Today. December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Dave Brubeck's Memorial Tribute at the Church of St. John of the Divine held Saturday May 11, 2013". allaboutjazz.com. May 12, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Brubeck, Dave, Sgt at Together We Served

- ^ "Dave Brubeck's No 1 Fan and Dave's Funeral" Archived August 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine by Don Albert, artlink.co.za, 27 December 2012

- ^ "Music: The Man on Cloud No. 7" (cover story), Time, November 8, 1954. (subscription required) Image Archived April 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hewett, Ivan (December 6, 2012). "Dave Brubeck: Endless curiosity combined with stubbornness". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (December 7, 2012). "Dave Brubeck". MSN Music. Microsoft. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ "Dave Brubeck". The Economist. December 15, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ "December Concerts at The Royal Conservatory | The Royal Conservatory of Music". Rcmusic.ca. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ "5/4 is Dave Brubeck Day!". Saxontheweb.net. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Crist, Stephen A. (2019). Dave Brubeck's Time out. New York. ISBN 9780190217716. OCLC 1089840773.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Chamberlin, Alan. "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". Ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Jazz great Brubeck wins US public diplomacy award" Archived April 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, AFP, April 8, 2008.

- ^ "Whatever Happened to Cultural Diplomacy?" Archived April 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, All About Jazz, April 19, 2008.

- ^ "Artists Dominate the 2008 'California Hall of Fame'". California Arts Council. May 28, 2008. Archived from the original on December 11, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- ^ "Dave Brubeck to Receive Honorary Doctorate". Berklee College of Music. August 19, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "The George Washington University's Commencement Line-Up Finalized – A. James Clark and Legendary Pianist and Composer Dave Brubeck to Receive Honorary Degrees; First Lady Michelle Obama to Headline Weekend Celebration". George Washington University. April 21, 2010. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "Kennedy Center Honorees for 2009 Are: Mel Brooks, Robert De Niro, Grace Bumbry, Bruce Springsteen and Dave Brubeck". The Washington Post. September 9, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Miles Davis Award – Festival International de Jazz de Montréal". Montrealjazzfest.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "In Dave Brubeck's Own Sweet Way". JazzTimes. Archived from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Henry, Emily (December 5, 2012). "Concord Remembers Native Dave Brubeck". Patch.com. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Dave Brubeck receives honorary doctorate in Theology – Théologie morale fondamentale Université de Fribourg". Unifr.ch. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Organ Debut, Honorary Degree for Jazz Great Dave Brubeck Highlight Eastman Weekend Celebration". Eastman School of Music. October 3, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "The Kennedy Center Honors". Kennedy-center.org. December 2, 2012. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "Legendary Pianist and Composer Dave Brubeck to Receive Honorary Degree from The George Washington University | Office of Media Relations | The George Washington University". Gwu.edu. December 7, 2009. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

External links

edit- Dave Brubeck at AllMusic

- Dave Brubeck at Find a Grave

- Dave Brubeck at IMDb

- Brubeck Institute at the University of the Pacific

- Rediscovering Dave Brubeck, PBS, December 16, 2001, documentary

- Brubeck biography and concert review in cosmopolis.ch

- University of the Pacific Library's Digital Collections website

- Dave Brubeck Interview at NAMM Oral History Library, September 21, 2006

- "Q&A Special: Dave Brubeck, a Life in Music" theartsdesk.com

- Interview: Dave Brubeck & the First Annual Maine Jazz Festival, Portland Magazine

- Dave Brubeck interview on BBC Radio 4, Desert Island Discs, January 8, 1998

- Thank you Dave Brubeck...for showing us yet again that music wells up in the most unlikely places! Includes the complete eight-part BBC interview of 1994, Unsquare Dances.