The Hotak dynasty (Pashto: د هوتکيانو ټولواکمني Persian: امپراتوری هوتکیان) was an Afghan monarchy founded by Ghilji Pashtuns that briefly ruled portions of Iran and Afghanistan during the 1720s.[2][3] It was established in April 1709 by Mirwais Hotak, who led a successful rebellion against the declining Persian Safavid empire in the region of Loy Kandahar ("Greater Kandahar") in what is now southern Afghanistan.[2]

Hotak dynasty | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1709–1738 | |||||||||||

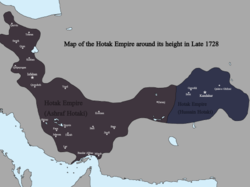

Hotak dynasty at its greatest extent | |||||||||||

| Capital | Kandahar (1709–1722), (1725–1738) Isfahan (1722–1729) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Pashto (poetry)[1] Persian (poetry)[a][1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||||

• 1709–1715 | Mirwais Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1715–1717 | Abdul Aziz Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1717–1725 | Mahmud Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1725–1730 | Ashraf Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1725–1738 | Hussain Hotak | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||

• Revolt by Mirwais Hotak | 21 April 1709 | ||||||||||

| 24 March 1738 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

In 1715, Mirwais died of natural causes and his brother Abdul Aziz succeeded him. He did not reign long as he was killed by his nephew Mahmud, who deposed the Safavid Shah and proclaimed his own rule over Iran. Mahmud in turn was succeeded by his cousin Ashraf following a palace coup in 1725. Ashraf also did not retain his throne for long, as the Iranian conqueror Nader-Qoli Beg (later Shah), leading the resurgent Safavid banner, defeated him at the Battle of Damghan of 1729. Ashraf Hotak was banished to what is now southern Afghanistan, confining Hotak rule to a small corner of their former empire. In 1738, Hotak rule ended when Nader Shah defeated Ashraf's successor Hussain Hotak after a lengthy siege of Kandahar. Subsequently, Nader Shah began re-establishing Iranian suzerainty over regions lost decades before to Iran's archrivals—the Ottoman and Russian Empires.[4]

History of the Hotak Dynasty

editRise to power and Reign of Mirwais Hotak

editDecline of the Safavids

editThe Shi'a Safavids ruled Loy Kandahar as their easternmost territory from the 16th century until the early 18th century. At the same time, the native Afghan tribes living in the area were Sunni Muslims. Immediately to the east was the powerful Sunni Mughal Empire, who occasionally fought wars with the powerful Safavids over the territory of southern Afghanistan.[5] The Khanate of Bukhara controlled the area to the north at the same time. By the late 17th century, the Safavids started to decline. With the death of Shah Abbas in 1629, succeeding Safavid rulers were less effective and caused the empire to decline. On 29 July 1694, Shah Suleiman died and Sultan Husayn took the throne.[6] Under his reign the problems worsened. Husayn barely left the palace during his reign, not an uncommon aspect of many later Safavid Shahs. Later Safavid rulers were immobile and their courts were riddled with factionalism unlike their more mobile ancestors who spent more time on campaigns and had smaller courts.[6] The government was weak and the army was ineffective. This power vacuum allowed tribal groups like the Turkmen, Baluch, Arabs, Kurds, Dagestanis, and Afghans to constantly raid frontier provinces.[6][7]

Governorship of Gurgin Khan

editIn 1704, the Safavid Shah Husayn appointed his Georgian subject and king of Kartli George XI (Gurgīn Khān), a convert to Islam, as the governor of Kandahar.[8][7] In early May 1704, George marched from Kerman and after a seven-week march; he crushed disturbances going on in the province at the time.[9][6][7] He soon encountered Mirwais Hotak, the mayor (kalantar) of Kandahar and one of the richest and most influential people among the Ghilzais.[9][7] At first Mirwais had good relations with the Georgians but it began to sour when Mirwais was removed from his position as mayor in 1706 and replaced by Alam Shah Afghan.[6]

The Georgians were hated throughout the province. They ruled with brutality towards the local population.[10] This would encourage the Ghilzais to revolt against Safavid rule, and Mirwais was involved in one of these revolts. Gurgin Khan found out and sent Mirwais to Isfahan.[6][9][7] While there, he saw the weakness of the Safavid court and complained about the brutality of Gurgin Khan. He turned the shah and his court against Gurgin Khan, and then went on a pilgrimage to Mecca. He managed to get a fatwa from the religious authorities approving Mirwais's plan to overthrow tyrannical Safavid rule. In the summer of 1708 or January 1709[11] he returned to Kandahar and waited for the opportunity to kill Gurgin Khan.[10][9][7]

Rebellion

editThat opportunity came in April 1709. The Kakar tribe refused to pay taxes and revolted, so Gurgin Khan and his men went out to campaign against them. Protected by the Ghaznavid Nasher Khans,[12] Mirwais and his men ambushed Gurgin Khan on April 21 and killed him.[13][9][7][6][10] They expelled the Georgian garrison from Kandahar and the surviving Georgians fled to Gereshk and waited.[9] When the Safavid court heard of this, they sent Kaikhosro Khan with 12,000 men to recapture Kandahar. He left Isfahan for Qandahar in November 1709,[9] and were aided by members of the Abdali tribe.[7][6][11] The army progressed slowly as the court was unwilling to help much, and they arrived at Farah in April–May[11] or November 1710.[9] In the summer of 1711 Kaikhosro marched to Kandahar and besieged it. The Ghilzais sued for peace but Kaikhosro refused to accept it, so they kept fighting. The Baluchis frequently harassed the Georgians and forced them to retreat on October 26.[9][7][6] The defenders of Kandahar emerged and pursued the Georgians, resulting in the death of Kaikhosro. Another Persian army was sent to Kandahar in 1712 but they never made it there as their commander died in Herat, leaving the Hotaks to their own devices. With this, Mirwais was able to extend his control over the entire province of Kandahar. After his peaceful passing in November 1715 from natural causes, his brother Abdul Aziz succeeded him; the latter was murdered later by Mirwais' son Mahmud after having only ruled for eighteen months.[9]

Invasion of Iran

editIn 1720, Mahmud's Afghan forces crossed the deserts of Sistan and captured Kerman.[14] He planned to conquer the Persian capital, Isfahan.[15] After defeating the Persian army at the Battle of Gulnabad on March 8, 1722, he proceeded to besiege Isfahan.[16] The siege lasted about six months and the people of Isfahan were in such a state of hunger that they were forced to eat rats and dogs.[17] On October 23, 1722, Sultan Husayn abdicated and acknowledged Mahmud as the new Shah of Persia.[18] For the next seven years until 1729, the Hotaks were the de facto rulers of most of Persia, and the southern areas of Afghanistan remained under their control until 1738.

The Hotak dynasty was a troubled and violent one from the very start as an internecine conflict made it difficult to establish permanent control. The majority of Persians rejected the leaders as usurpers, and the dynasty lived under great turmoil due to bloody succession feuds that made their hold on power tenuous. After the massacre of thousands of civilians in Isfahan – including more than three thousand religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family – the Hotak dynasty was eventually removed from power in Persia.[19]

Decline

editAshraf Hotak took over the monarchy following Shah Mahmud's death in 1725. He had to deal with a Safavid loyalist movement in the south led by Sayyed Ahmad, who had taken over much of Fars, Hormozgan, and Kerman.[20] Ashraf's army was defeated in the October 1729 at the Battle of Damghan by Nader Shah Afshar, an Iranian soldier of fortune from the Afshar tribe, and the founder of the Afsharid dynasty that replaced the Safavids in Persia. Nader Shah had driven out and banished the remaining Ghilji forces from Persia and began enlisting some of the Abdali Afghans of Farah and Kandahar in his military. Nader Shah's forces, among them Ahmad Shah Abdali and his 4,000 Abdali troops, went on to conquer Kandahar in 1738. They besieged and destroyed the last Hotak seat of power, which was held by Hussain Hotak (or Shah Hussain).[15][21] Nader Shah then built a new town nearby, named "Naderabad" after himself. The Abdalis were then restored to the general area of Kandahar, with the Ghiljis being pushed back to their former stronghold of Kalat-i Ghilji. This arrangement lasts to the present day.

List of rulers

edit| Name | Picture | Reign started | Reign ended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mirwais Hotak Woles Mashar |

1709 | 1715 | |

| Abdul Aziz Hotak Emir |

1715 | 1717 | |

| Mahmud Hotak Shah |

1717 | 1725 | |

| Ashraf Hotak Shah |

1725 | 1729 | |

| Hussain Hotak Emir |

1729 | 1738 |

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Bausani 1971, p. 63.

- ^ a b Malleson, George Bruce (1878). History of Afghanistan, from the Earliest Period to the Outbreak of the War of 188. London: Elibron.com. p. 227. ISBN 1402172788. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ Ewans, Martin (2002). Afghanistan: a short history of its people and politics. New York: Perennial. p. 30. ISBN 0060505087. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 9780823938636. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Matthee, Rudi (2012). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84511-745-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Axworthy, Michael (2010-03-24). Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-347-4.

- ^ Nadir Shah and the Afsharid Legacy, The Cambridge history of Iran: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic, Ed. Peter Avery, William Bayne Fisher, Gavin Hambly and Charles Melville, (Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lockhart, Laurence (1958). The Fall of the Safavi Dynasty and the Afghan Occupation of Persia. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Otfinoski, Steven Bruce (2004). Afghanistan. Infobase Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780816050567. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ a b c Nejatie, Sajjad (November 2017). The Pearl of Pearls: The Abdālī-Durrānī Confederacy and Its Transformation under Aḥmad Shāh, Durr-i Durrān (Thesis thesis). Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ Runion, Meredith L. (2007). The History of Afghanistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33798-7.

- ^ Noelle-Karimi, Christine (2014). The Pearl in Its Midst: Herat and the Mapping of Khurasan (15th-19th Centuries). Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-7202-4.

- ^ "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 29. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ a b "Last Afghan empire". Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree and others. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ "Account of British Trade across the Caspian Sea". Jonas Hanway. Centre for Military and Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present, page 78

- ^ Axworthy pp.39-55

- ^ "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 31. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Floor, Willem M. (1998). The Afghan Occupation of Safavid Persia, 1721-1729. Peeters Publishers & Booksellers. ISBN 978-2-910640-05-7.

- ^ "AFGHANISTAN x. Political History". D. Balland. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2020-05-26. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

Sources

edit- Bausani, Alessandro (1971). "Pashto Language and Literature". Mahfil. 7 (1/2 (Spring - Summer)). Asian Studies Center: 55–69.

External links

edit- Balland, D. (2011) [1987]. "AŠRAF ḠILZAY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 796–797.

- Tucker, Ernest (2009). "Ashraf Ghilzay". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.