The Honeymoon Killers is a 1970 American crime film written and directed by Leonard Kastle, and starring Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco. Its plot follows an overweight nurse who is seduced by a handsome con man, with whom she embarks on a murder spree of single women. The film was inspired by the true story of Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck, the notorious "lonely hearts killers" of the 1940s.

| The Honeymoon Killers | |

|---|---|

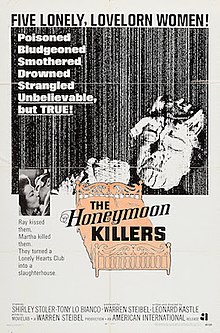

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Leonard Kastle |

| Written by | Leonard Kastle |

| Produced by | Warren Steibel |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Oliver Wood |

| Edited by | Richard Brophy Stanley Warnow |

| Music by | Gustav Mahler |

Production company | Roxanne Company[1] |

| Distributed by | Cinerama Releasing Corporation American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | ~$200,000[a] |

| Box office | $11 million[3] |

Filmed primarily in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, production of The Honeymoon Killers began with Martin Scorsese as its appointed director. However, after Scorsese was fired early into the shoot, he was replaced by Donald Volkman, a maker of industrial films, who lasted only two weeks[5] before Kastle, who had helped develop the film, took over directing. The film's score comprises the first movement of the 6th Symphony and a section of the 5th Symphony of Gustav Mahler. Released in early 1970, the film was met with critical praise for its performances as well as its realism.

The Honeymoon Killers went on to achieve cult status as well as critical recognition, and was named by François Truffaut as his "favorite American film." A digital restoration of the film was released on DVD by The Criterion Collection in 2003, and again in 2015 with a new digital transfer.

Plot

editMartha Beck is a sullen, overweight nursing administrator living in Mobile, Alabama, with her elderly mother. Martha's friend Bunny surreptitiously submits Martha's name to a "lonely hearts" club, which results in a letter from Raymond Fernandez of New York City. Overcoming her initial reluctance, Martha corresponds with Ray and becomes attracted to him. He visits Martha in Alabama and seduces her. Thereafter, having secured a loan from her, Ray sends Martha a Dear Jane letter, and Martha enlists Bunny's aid to call him with the (false) news that she has attempted suicide.

Ray allows Martha to visit him in New York, where he reveals he is a con man who makes his living by seducing and then swindling lonely women. Martha is unswayed by this revelation. At Ray's directive, and so she can live with him, Martha puts her mother in a nursing home. Martha's embittered mother disowns her for abandoning her. Martha insists on accompanying Ray at his "work." Woman after woman accepts the attentions of this suitor who goes courting while always within sight of his "sister". Ray promises Martha he will never sleep with any of the other women but complicates his promise by marrying pregnant Myrtle Young. After Young aggressively attempts to bed the bridegroom, Martha gives her a large dose of pills, and Ray puts the drugged woman on a bus. Her death thereafter escapes immediate suspicion.

The swindlers move on to their next target, and after catching Ray becoming intimate with the woman, Martha attempts to drown herself. To placate her, Ray rents a house in Valley Stream, a suburb of New York City. He becomes engaged to the elderly Janet Fay of Albany, and takes her to the house he shares with Martha. Janet gives Ray checks for $10,000 but then becomes suspicious of the two. When Janet tries to contact her family, Martha bludgeons her with a hammer before she and Ray strangle her. They bury her body beneath their cellar floor in her trunk, tossing into the grave the two framed depictions of Jesus that, Martha notes sarcastically, she'd told them she took everywhere she went.

Next, they spend several weeks living in Michigan with the widowed Delphine Downing and her young daughter. Delphine, younger and prettier than most of Ray's conquests, confides in Martha, hoping that she will help her persuade Ray to marry her as soon as possible because she is pregnant with Ray's child. Martha is in the midst of drugging and smothering Delphine when the woman's daughter enters the room with Ray. He shoots Delphine in the head, and Martha drowns the daughter in the cellar. Ray tells Martha that he has to move on to one more woman, this one in New Orleans, and then he will marry Martha; he repeats his promise never to have sex with any of his marks. Realizing that Ray will never stop lying to her, Martha calls the police and waits calmly for them to arrive.

The epilogue takes place four months later, with Martha and Ray in jail. As she leaves the cellblock for the first day of their trial, Martha receives a letter from Ray in which he tells her that, despite everything, she is the only woman he ever loved. On-screen titles state that Martha and Raymond were electrocuted at Sing Sing on March 8, 1951.[b]

Cast

edit- Shirley Stoler as Martha Beck

- Tony Lo Bianco as Raymond Fernandez

- Doris Roberts as Bunny

- Marilyn Chris as Myrtle Young

- Barbara Cason as Evelyn Long

- Dortha Duckworth as Mrs. Beck

- Mary Jane Higby as Janet Fay

- Kip McArdle as Delphine Downing

- Mary Breen as Rainelle Downing

- Ann Harris as Doris Acker

- Elsa Raven as Matron

- Mary Engel as Lucy

- Guy Sorel as Mr. Dranoff

Production

editDevelopment

editThe film was the first for producer Warren Steibel (known as the producer of television's Firing Line), writer/director Leonard Kastle (known as a composer), and cinematographer Oliver Wood. A wealthy friend of Steibel, Leon Levy, suggested to Steibel that he make a film, and gave Steibel $150,000, the amount that Steibel suggested it would cost.[2] After deciding the film would be about "The Lonely Hearts Killers", Steibel asked Kastle, his roommate, to do some research on the subject; financial limitations led Steibel to ask his friend to write the screenplay.[2]

Commenting on the aims of the film, Steibel said: "We wanted to do an honest movie about murders. These are not charming people. They are sleazy people—but fascinating. You won't come out of the theatre feeling sorry for the killers like in some movies. It is not romanticized."[6]

Historical accuracy

editAlthough the film is inspired by true events and uses the real names of "The Lonely Hearts Killers" and of those they murdered, as well as the true locations of the crimes, the film takes substantial liberties with the facts, contrary to the opening titles. Although the actual events unfolded in the late 1940s, the film is seemingly set during an undetermined period even though it was clearly filmed during the late 1960s despite an end credit appearing stating that the two were executed in 1951. The film presents the killings as commencing with Beck's entrance on the scene and as a consequence of her jealousy. In contrast, it is believed that Fernandez had murdered at least one of the victims of his swindling, Jane Wilson Thompson, before meeting Beck, in order to pose as Thompson's widower and claim title to her property, including the apartment in New York where Beck joined him.[7][8] There is no acknowledgment that Beck was divorced with two children,[9] whom she abandoned on Fernandez's orders (her abandonment of her mother is substituted); nor is there mention of Fernandez's legal wife and four children in Spain.[10]

The film depicts Beck's surrender of herself and Fernandez, but that implied demonstration of remorse is contrary to the historical record: neighbors noticed the Downings' disappearance, and Beck and Fernandez were apprehended at the Downing house after returning from an evening at the movies.[11][12]

Casting

editShirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco, both stage actors in New York, were cast in the leading roles.[4] Stoler, also a singer, was referred by her friend, Marilyn Chris, who had been cast in the role of Myrtle: "It was by accident that I got the role," Stoler stated. "I had just returned from Europe where I had been singing in cafes and had no job prospect."[13] Stoler and Chris had worked together in stage productions at The Living Theatre in Manhattan,[13] while Lo Bianco had performed on Broadway.[4]

Filming

editPrincipal photography of The Honeymoon Killers began in August 1968, concluding in October.[13] During production, it had the working title Dear Martha.[6] The majority of the film was shot in Pittsfield, Massachusetts[4] and Albany, New York. Steibel initially hired Martin Scorsese to direct, but Scorsese was fired for working too slowly, but a few scenes that he had shot were included in the final film.[14] Scorsese conceded that he had "been fired with pretty good reason... It was a 200-page script and I was shooting everything in master shots with no coverage."[14] He was replaced by Donald Volkman, a maker of industrial films, who lasted only two weeks before being replaced by Leonard Kastle.[5]

Budgetary constraints meant that the actors did their own hair and makeup, and special effects were not fancy. In the scene in which Martha bludgeons Janet Fay with a hammer, "condoms containing glycerine and red dye were affixed to the head of the victim with plaster of Paris. The hammer, a balsa-wood prop, had a pin at the end. When the pin pricked the condoms, the blood began to flow."[2]

Musical score

editThe film's score features portions of the 6th and 5th Symphonies of Gustav Mahler.[15] Scholar Martin Rubin asserts that the incorporation of Mahler's symphonies "catapults us outside the often unbearable events and at the same time plunges us inside the main characters' (especially Martha's) inflated and distorted interpretations of those events."[16] Film historian Rob Craig notes that the dramatic score gives the film an "uncanny essence of a Greek tragedy."[17]

Style

editScholars and critics have noted The Honeymoon Killers for its black-and-white photography and camerawork that evokes those of a documentary film.[18] Critics also observed the film's streaks of realism at the time of its release.[c] Film scholar Martin Rubin notes that The Honeymoon Killers "contains strong undercurrents of documentary realism, but it pushes them to the point where they erode the balance of realism and expressionism that provides a basic framework for the Hollywood style."[21] Rubin likens the film to a "putrescent version of Norman Rockwell's America."[22]

While its unglamorous depiction of violence has been noted by critics,[23] Rubin contests that the film is not "completely heartless" due to the "discomfiting vulnerability of the victims and the undiluted horror of their deaths."[22] Craig, however, describes the film as a "harrowing depiction of evil."[1]

Release

editBox office

editAmerican International Pictures (AIP) acquired distribution rights to the film in September 1969, and went as far as producing key art, publicity stills, and promotional posters.[17] Sources differ as to whether AIP actually released the film; some claim that AIP gave it a brief theatrical run before it was dropped from AIP's roster.[d] Craig theorizes that the studio ultimately opted out of releasing the film because of its "extremely gruesome and misanthropic" content.[17]

The Honeymoon Killers was distributed by Cinerama Releasing Corporation,[25] premiering in New York City on February 4, 1970.[26] Despite receiving some critical praise, the film "performed weakly" at the U.S. box office.[2] Jake Eberts later wrote that the entire budget of $250,000 was provided by Leon Levy.[3] The film ultimately earned $11 million internationally, but Levy recouped none of his investment.[3] The film was a "modest financial success" in Britain and France.[2]

Critical response

editPrior to its release, Variety magazine said that The Honeymoon Killers was "made with care, authenticity and attention to detail."[27] Later, Roger Greenspun of The New York Times praised the film, writing: "Kastle's film succeeds as a kind of chamber drama of desperate attraction and violent death. Although it is profoundly involved with the quality of individual middle-class American lives, it completely subordinates anecdote to action and pathos, even the pathos of its central characters, to passion. The secondary performances range from acceptable to excellent."[28] Harvey Taylor of the Detroit Free Press also championed the performances as "excellent," particularly those of Stoler and Lo Bianco, though he conceded that the film's grittiness left him "mildly nauseated."[29]

The Dayton Daily News noted the film's realism: "Done with grainy black-and-white film, poor-to-sloppy editing, one-position camera, secondhand furniture sets—there's a tawdry truth to the bizarre story of an unreal, grotesque love affair between Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez."[19] Stephen Allen of New Jersey's Courier-Post made similar observations that the photography has a "harsh documentary or underground film quality that lends an air of authenticity," and also praised the realistic casting.[20]

Upon a revival screening in 1992, Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times praised the film, writing: "This quality of being true to itself is The Honeymoon Killers's greatest strength. Writer-director Kastle, who unaccountably never made another feature, is in perfect control of his material here, understanding it thoroughly and making sure that everything, from the harsh lighting to the flat staging to the snippets of Mahler on the soundtrack, unite to enhance the rawness and relentlessness of the film."[15] A 2003 review by The A.V. Club concludes by noting that the film's "nauseous mixture of laughs and shocks, and the fact that real passion drives Kastle's characters even when they plot against each other, is what makes The Honeymoon Killers such an enduring one-off. It works, as Gary Giddins argues in the liner notes of the restored DVD edition, 'as the perfect product of the same anxious, permissive age that produced Waters, Night of the Living Dead, and blaxploitation. But it holds up just as well as a weirdly timeless love story with a body count.'"[30]

The film holds a 95% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 8/10, based on 19 reviews.[31]

The film was reportedly banned in Australia upon its release in 1970 until the late 1980s after being deemed "violent, indecent and obscene" by the Australian censorship board.[32]

Home media

editThe film was issued on DVD by The Criterion Collection (under license from MGM, the owner of the AIP library) in July 2003.[33] A newly restored Blu-ray and DVD edition was released by the Criterion Collection in 2015.[34]

Legacy

editIn the decades following its release, The Honeymoon Killers developed a cult following.[14] French director François Truffaut heralded it as his "favorite American film."[2]

Notes

edit- ^ Estimates of the film's production budget vary: A 1992 retrospective in The New York Times states $150,000[2] though other sources state $250,000.[3] A 1970 article in The Philadelphia Inquirer notes a $200,000 budget.[4]

- ^ Although the real-life Beck and Fernandez were arrested originally in Michigan and charged with the murders of the Downings, those prosecutions were suspended and they were extradited to New York to be tried for the murder of Janet Fay, because New York, unlike Michigan, had the death penalty. It was for the murder of Fay that they were convicted and executed.

- ^ The Dayton Daily News published a review that noted the film's photography and editing contributed to a realistic depiction of events.[19] Similarly, Stephen Allen of the Courier-Post likened the film to an "underground film" and remarked the realistic depiction of its characters.[20]

- ^ Craig states that AIP likely dropped the film because of its violent and controversial content.[17] A September 1969 article noting that the film had received a "rave review" in Variety states that AIP would be distributing it.[24] However, by December, the New York Daily News had reported that Cinerama Releasing Corporation was releasing the film.[25] Despite this, Craig states there is "some evidence" that AIP did serve as the film's distributor in Canada.[17]

References

edit- ^ a b c Craig 2019, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grimes, William (October 20, 1992). "Behind the Filming of 'The Honeymoon Killers'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Eberts & Illott 1990, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Barbara L. (February 13, 1970). "That's show business". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Grimes, William (20 October 1992). "Behind the Filming of 'The Honeymoon Killers'". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Wood, Ben (December 9, 1969). "Low-Budget Movie May Make Cash Registers Ring". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 36 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Study Love Notes for Clue to Identity of Killer's 'Irene'". Milwaukee Journal. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. March 5, 1949. p. 16.

- ^ "Fernandez, Woman Face Michigan Murder Trial". Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, New York. March 2, 1949. pp. 1, 17.

- ^ "Killer Asks for Children's Photos". Record-Eagle. Traverse City, Michigan. September 16, 1949. p. 11.

- ^ "Says He Was Charming When He Married Her". The Lowell Sun. Lowell, Massachusetts. March 2, 1949. p. 1.

- ^ "Lonely Heart' Killings Bared: Widow and Child Buried in Concrete". News-Palladium. Benton Harbor, Michigan. March 1, 1949. p. 1.

- ^ "Justice for Mr. and Mrs. Bluebeard". Sunday Press. Binghamton, New York. February 18, 1951. p. 8-C.

- ^ a b c Adams, Marjory (February 17, 1970). "Fat actresses don't have to play funny roles". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Raymond 2014, p. 20.

- ^ a b Turan, Kenneth (October 30, 1992). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'The Honeymoon Killers' Returns With a Vengeance". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019.

- ^ Rubin 1999, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e Craig 2019, p. 193.

- ^ Rubin 1999, pp. 46–48.

- ^ a b "Tight Budget Gives Realism to 'The Honeymoon Killers'". Dayton Daily News. Dayton, Ohio. March 5, 1970. p. 41 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Allen, Stephen (February 27, 1970). "Crime in 1950s Starkly Depicted". Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rubin 1999, p. 46.

- ^ a b Rubin 1999, p. 49.

- ^ Rubin 1999, pp. 49–52.

- ^ "Feature Film Made Here draws Rave From Variety". The Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts. September 20, 1969. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Distribution Pact". New York Daily News. New York City, New York. December 21, 1969. p. 170 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Honeymoon Killers". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019.

- ^ The Honeymoon Killers, a January 1, 1969 review from Variety magazine

- ^ Greenspun, Roger (February 5, 1970). "Screen: Kastle's 'Honeymoon Killers':Theme Recalls Lonely Hearts Murders". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Harvey. "'The Honeymoon Killers,' A Gruesome Tale of Horror". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. p. 6-C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ The Honeymoon Killers (DVD), a July 14, 2003 review by Keith Phipps for The A.V. Club.

- ^ Film profile, rottentomatoes.com; accessed July 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Honeymoon Killers". Australia: Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn (2003). "DVD Savant Review: The Honeymoon Killers". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017.

- ^ Bowen, Chuck (October 2, 2015). "Review: The Honeymoon Killers". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019.

Sources

edit- Craig, Rob (2019). American International Pictures: A Comprehensive Filmography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-66631-0.

- Eberts, Jake; Illott, Terry (1990). My Indecision Is Final. London, England: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-14889-9.

- Raymond, Marc (2014). "How Scorsese Became Scorsese". In Baker, Aaron (ed.). A Companion to Martin Scorsese. Malden, Massachusetts: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 17–37. ISBN 978-1-444-33861-4.

- Rubin, Martin (1999). "The Grayness of Darkness: The Honeymoon Killers and Its Impact on Psycho Killer Cinema". In Sharrett, Christopher (ed.). Mythologies of Violence in Postmodern Media. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. pp. 41–64. ISBN 978-0-814-32742-5.

External links

edit- The Honeymoon Killers at IMDb

- The Honeymoon Killers at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Honeymoon Killers at the TCM Movie Database

- The Honeymoon Killers at AllMovie

- The Honeymoon Killers at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Honeymoon Killers: Broken Promises an essay by Gary Giddins at the Criterion Collection