Gilda is a 1946 American film noir directed by Charles Vidor and starring Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford.

| Gilda | |

|---|---|

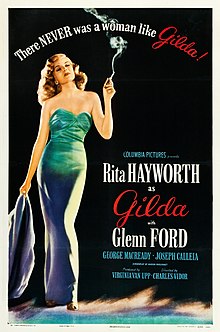

Theatrical release poster, "Style B" | |

| Directed by | Charles Vidor |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Adaptation by | |

| Story by | E.A. Ellington |

| Produced by | Virginia Van Upp |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Rudolph Maté |

| Edited by | Charles Nelson |

| Music by | M. W. Stoloff Marlin Skiles |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | Columbia Pictures |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[1] |

| Box office | $6 million (rentals)[1] |

The film is known for cinematographer Rudolph Maté's lush photography, costume designer Jean Louis's wardrobe for Hayworth (particularly for the dance numbers), and choreographer Jack Cole's staging of "Put the Blame on Mame" and "Amado Mio", sung by Anita Ellis. Over the years Gilda has gained cult classic status.[2][3][4] In 2013, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[5][6][7]

Plot

editJohnny Farrell, an American newly arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, wins a lot of money cheating at craps. He is rescued from a robbery attempt by a complete stranger, Ballin Mundson. Although Farrell is warned not to cheat at an illegal high-class casino he tells him about, he ignores his advice. After winning at blackjack, he is taken to see the casino's owner, who turns out to be Mundson. Farrell talks him into hiring him and soon becomes Mundson's trusted casino manager.

Mundson returns from a trip and announces he has an extremely beautiful new wife, Gilda, whom he has married after only knowing her for a day. Johnny and she instantly recognise each other from the past, though both deny it when he questions them. Mundson assigns Farrell to watch over Gilda. The pair are consumed with hatred for each other, and she cavorts with men at all hours in increasingly more blatant efforts to enrage Johnny, and in return he grows more spiteful towards her.

Mundson is visited by two German mobsters. Their organisation had financed a tungsten cartel, with everything put in Mundson's name in order to hide their connection to it. They have decided that it is safe to take over the cartel now that World War II has ended, but Mundson refuses to transfer ownership.

The Argentinian police are suspicious of the Germans and assign agent Obregón to try to obtain information from Farrell, but he knows nothing about this aspect of Mundson's operations. The Germans return to the casino during a carnival celebration, and Mundson ends up deliberately shooting and killing one of them..

Farrell rushes to take Gilda to safety. Alone in Mundson's house, they have another confrontation and, after declaring their undying hatred for each other, passionately kiss. After hearing the front door slam, they realise Mundson has overheard them, and a guilt-ridden Farrell pursues him to a waiting private airplane. The plane explodes in midair and plummets into the ocean. Mundson parachutes to safety. Farrell, unaware of this, concludes that he is dead.

Gilda inherits his estate. Farrell and she immediately marry, but unknown to her Johnny is marrying her to punish her for her betrayal of Mundson, which is hypocritical, since he also betrayed Mundson's trust. He abandons her, but has her followed day and night by his men to torment her. Gilda tries to escape the tortured marriage a number of times, but Farrell thwarts every attempt.

Obregón confiscates the casino and informs Farrell that Gilda was never truly unfaithful to Mundson or to him, prompting Farrell to try to reconcile with her as he prepares to return home to the U.S. At that moment, Mundson reappears, revealing his faked suicide. He tries to kill both Gilda and Farrell, but the casino worker, Uncle Pío, fatally stabs him in the back. When Obregón arrives, Johnny tries to take the blame for the murder, but Obregón points out that, since Mundson was already declared legally dead, he can't arrest him.

Farrell gives Obregón incriminating documents from Mundson's safe. He and Gilda finally reconcile, agreeing to go home together.

-

Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford) and Gilda (Rita Hayworth)

-

"Gilda, are you decent?"

Cast

edit- Rita Hayworth as Gilda Mundson

- Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell

- George Macready as Ballin Mundson

- Joseph Calleia as Detective Mauricio Miguel Obregón

- Steven Geray as Uncle Pío

- Joe Sawyer as Casey

- Gerald Mohr as Captain Delgado

- Mark Roberts as Gabe Evans

- Ludwig Donath as German

- Don Douglas as Thomas Langford

- Lionel Royce as German

- George J. Lewis as Huerta

Cast notes

- Anita Ellis dubbed the singing voice of Rita Hayworth in all songs.[note 1]

Production

editGilda was developed by producer Virginia Van Upp as a vehicle for Hayworth, who had mostly been known for her roles in musical comedies at that time.[10] The story was originally set to be an American gangster film directed by Edmund Goulding.[11] However, the location of story was changed to Buenos Aires after objections from censor Joseph Breen and the replacement of Goulding with Charles Vidor.[11]

Gilda was filmed from September 4 to December 10, 1945.[10][11] During filming, Hayworth and Ford began an extensive affair that would last until Hayworth was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in the early 1980s.[12][13][14][15]

Hayworth's introductory scene was shot twice. While the action of her popping her head into the frame and the subsequent dialogue remains the same, she is dressed in different costumes—in a striped blouse and dark skirt in one film print, and the more famous off-the-shoulder dressing gown in the other.[citation needed]

Reception

editWhen first released, the film earned mixed to positive reviews. Variety liked the film and wrote, "Hayworth is photographed most beguilingly. The producers have created nothing subtle in the projection of her s.a. [sex appeal], and that's probably been wise. Glenn Ford is the vis-a-vis, in his first picture part in several years ... Gilda is obviously an expensive production—and shows it. The direction is static, but that's more the fault of the writers."[16] Reviewing the film for The New York Times, Bosley Crowther gave the film a negative review, admitting he did not like or understand the movie, but praised Ford as having "a certain stamina and poise in the role of a tough young gambler."[17]

Gilda was screened in competition at the 1946 Cannes Film Festival, the first time the festival was held.[18] In its release, the film earned theatrical rentals of $3,750,000 in the United States and Canada,[19] and $6 million worldwide.[1]

In retrospect, the film has become critically acclaimed. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported that 90% of critics gave the film a positive review, based on 67 reviews.[20] More recently, film critic Emanuel Levy wrote a positive review: "Featuring Rita Hayworth in her best-known performance, Gilda, released just after the end of WWII, draws much of its peculiar power from its mixture of genres and the way its characters interact with each other ... Gilda was a cross between a hardcore noir adventure of the 1940s and the cycle of 'women's pictures.' Imbued with a modern perspective, the film is quite remarkable in the way it deals with sexual issues."[21] The A.V. Club said "Part of Gilda's fascination is the way that it complicates the idea of the femme fatale. (...) Hayworth plays Gilda with a layer of bravado that masks deep insecurity" but mentioned that the unusual happy ending for a noir almost ruined the film experience.[22]

Operation Crossroads nuclear test

editAttesting to its immediate success, it was widely reported that an atomic bomb to be tested at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands would bear the film's title above an image of Hayworth, a reference to her bombshell status. The bomb was decorated with a photograph of Hayworth cut from the June 1946 issue of Esquire magazine; above it was stenciled the device's nickname, "Gilda", in two-inch black letters.[23]

Although the gesture was meant as a compliment, Hayworth was deeply offended.[24] According to Orson Welles, her husband at the time of filming Gilda, Hayworth believed it to be a publicity stunt from Columbia executive Harry Cohn and was furious. Welles told biographer Barbara Leaming: "Rita used to fly into terrible rages all the time, but the angriest was when she found out that they'd put her on the atom bomb. Rita almost went insane, she was so angry. ... She wanted to go to Washington to hold a press conference, but Harry Cohn wouldn't let her because it would be unpatriotic." Welles tried to persuade Hayworth that the whole business was not a publicity stunt on Cohn's part, that it was simply homage to her from the flight crew.[25]: 129–130

Memorabilia

editThe two-piece costume worn by Hayworth in the "Amado Mio" nightclub sequence was offered as part of the "TCM Presents ... There's No Place Like Hollywood" auction November 24, 2014, at Bonhams in New York.[26] It was estimated that the costume would fetch between $40,000 and $60,000; in the event it sold for $161,000 (equivalent to $207,000 in 2023).[27]

Home media

editIn January 2016 The Criterion Collection released DVD and Blu-ray Disc versions of Gilda, featuring a new 2K digital film restoration, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray version.[28]

Legacy

editHayworth later came to resent the film and its effect on her image. Hayworth once said with some bitterness, "Men go to bed with Gilda, but wake up with me".[25]: 122 This quote was referenced by Anna Scott, the fictional actress played by Julia Roberts in the film Notting Hill.

Hayworth's performance as Gilda lent itself to the Stephen King novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption in the form of a poster hanging on the wall of prisoner Andy Dufresne, who used it to cover the hole in the wall he used to escape. In the novella's film adaption, the film is shown to the prisoners for movie night. The film has also been watched by characters in Hero, Girl, Interrupted, and The Thirteenth Floor, as well as episodes of Joan of Arcadia, The Blacklist, and The Penguin.

In Mulholland Drive, the amnesiac protagonist played by Laura Harring proclaims her name as 'Rita' after seeing a poster of Gilda on the wall, a reference to the actress Hayworth.

The film has been shown on Turner Classic Movies at the request of guest hosts several times. In 2015, actress Diahann Carroll chose the film and expressed admiration for Hayworth and her performance in the film.[29] Guest hosts Joan Collins and Debra Winger have also chosen and discussed the film.

Notes

edit- ^ There were claims made that Hayworth had sung the acoustic guitar version of "Put the Blame on Mame", but this was untrue. Ellis dubbed all of the vocal parts since both their voices could not be used, Ellis's singing voice was too unlike Hayworth's for Hayworth's voice to be used in different parts of the film.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c "Wall St. Researchers' Cheery Tone". Variety. November 7, 1962. p. 7.

- ^ Grossini, Giancarlo (1 January 1985). "Dizionario del cinema giallo: tutto il delitto dalla A alla Z". EDIZIONI DEDALO – via Google Books.

- ^ "Gilda - review". April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Gilda (1946): Charles Vidor's Erotic Film Noir–Sexual Repression, Perversion, Masochism, and Latent Homosexuality | Emanuel Levy".

- ^ O'Sullivan, Michael (December 18, 2013). "Library of Congress announces 2013 National Film Registry selections". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ "Cinema with the Right Stuff Marks 2013 National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Truhler, Kimberly (October 17, 2014). "Style Essentials—Femme Fatale Rita Hayworth Puts the Blame in 1946's Gilda". GlamAmor. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Kobal, John (1982). Rita Hayworth : the time, the place, and the woman. Internet Archive. New York : Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-05634-9.

- ^ a b "AFI Movie Club: Gilda". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c "GILDA (1946)". American Film Institute. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Ford, Peter (2011). Glenn Ford: A Life (Wisconsin Film Studies). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 62, 63 ISBN 978-0-29928-154-0

- ^ King, Susan (April 11, 2011). "A Ford fiesta". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Glenn Ford: A Life – Book Notes". www.glennfordbio.com. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Ford celebrates his 90th after 15 years of seclusion". Deseret News. May 2, 2006. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Gilda". Variety. March 20, 1946. p. 8. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (March 15, 1946). "The Screen; Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford Stars of 'Gilda' at Music Hall". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ "Official Selection 1946". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ "60 Top Grossers of 1946". Variety. January 8, 1947. p. 8.

- ^ "Gilda | Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "details.cfm - Emanuel Levy". Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "There's more to Gilda than just an iconic hair flip by Rita Hayworth". The A.V. Club. January 16, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "Atomic Goddess Revisited: Rita Hayworth's Bomb Image Found". CONELRAD Adjacent (blog). August 13, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ Krebs, Albin (May 16, 1987). "Rita Hayworth, Movie Legend, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Leaming, Barbara (1989). If This Was Happiness: A Biography of Rita Hayworth. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-81978-6.

- ^ "TCM Presents ... There's No Place Like Hollywood" (PDF). Bonhams, sale 22196, lot 244, catalog for auction November 24, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ^ "TCM Presents ... There's No Place Like Hollywood". Bonhams, sale 22196, lot 244, November 24, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "Gilda". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "TCM Guest Programmer Diahann Carroll 3of4 Gilda (Intro)". YouTube. February 19, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

External links

edit- Gilda an essay by Kimberly Truhler on the National Film Registry website

- Gilda at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Gilda at IMDb

- Gilda at aenigma

- Gilda at the TCM Movie Database

- Gilda at AllMovie

- Gilda at Rotten Tomatoes

- Photos of Rita Hayworth in Gilda by Ned Scott

- "The Long Shadow of Gilda" an essay by Sheila O'Malley at the Criterion Collection