Francesco Borromini (/ˌbɒrəˈmiːni/,[1] Italian: [franˈtʃesko borroˈmiːni]), byname of Francesco Castelli (Italian: [kaˈstɛlli]; 25 September 1599 – 2 August 1667),[2] was an Italian architect born in the modern Swiss canton of Ticino[3] who, with his contemporaries Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona, was a leading figure in the emergence of Roman Baroque architecture.[4][5]

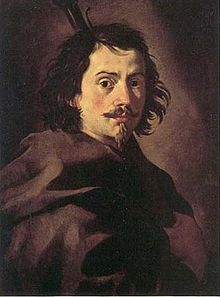

Francesco Borromini | |

|---|---|

Borromini (anonymous youth portrait) | |

| Born | Francesco Castelli 25 September 1599 |

| Died | 2 August 1667 (aged 67) |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Sant'Agnese in Agone, Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza, Oratorio dei Filippini |

A keen student of the architecture of Michelangelo and the ruins of Antiquity, Borromini developed an inventive and distinctive, if somewhat idiosyncratic, architecture employing manipulations of Classical architectural forms, geometrical rationales in his plans and symbolic meanings in his buildings. He seems to have had a sound understanding of structures, which perhaps Bernini and Cortona, who were principally trained in other areas of the visual arts, lacked. His soft lead drawings are particularly distinctive. He appears to have been a self-taught scholar, amassing a large library by the end of his life.

His career was constrained by his personality. Unlike Bernini who easily adopted the mantle of the charming courtier in his pursuit of important commissions, Borromini was both melancholic and quick in temper which resulted in his withdrawing from certain jobs.[6] His conflicted character led him to a death by suicide in 1667.

Probably because his work was idiosyncratic, his subsequent influence was not widespread but is apparent in the Piedmontese works of Guarino Guarini and, as a fusion with the architectural modes of Bernini and Cortona, in the late Baroque architecture of Northern Europe.[7] Later critics of the Baroque, such as Francesco Milizia and the English architect Sir John Soane, were particularly critical of Borromini's work. From the late nineteenth century onwards, interest has revived in the works of Borromini and his architecture has become appreciated for its inventiveness.

Early life and first works

editBorromini was born at Bissone,[8] near Lugano in today's Ticino, which was at the time a bailiwick of the Swiss Confederacy. He was the son of a stonemason and began his career as a stonemason himself. He soon went to Milan to study and practice his craft.[9] He moved to Rome in 1619 and started working for Carlo Maderno, his distant relative, at St. Peter's and then also at the Palazzo Barberini. When Maderno died in 1629, he and Pietro da Cortona continued to work on the palace under the direction of Bernini. Once he had become established in Rome, he changed his name from Castelli to Borromini, a name deriving from his mother's family and perhaps also out of regard for St Charles Borromeo.[10]

Major works

editSan Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (San Carlino)

editIn 1634, Borromini received his first major independent commission to design the church, cloister and monastic buildings of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (also known as San Carlino). Situated on the Quirinal Hill in Rome, the complex was designed for the Spanish Trinitarians, a religious order. The monastic buildings and the cloister were completed first after which construction of the church took place during the period 1638-1641 and in 1646 it was dedicated to San Carlo Borromeo. The church is considered by many to be an exemplary masterpiece of Roman Baroque architecture. San Carlino is remarkably small given its significance to Baroque architecture; it has been noted that the whole building would fit into one of the dome piers of Saint Peter's.[11][12][13]

The site was not an easy one; it was a corner site and the space was limited. Borromini positioned the church on the corner of two intersecting roads. Although the idea for the serpentine façade must have been conceived fairly early on, probably in the mid-1630s, it was only constructed towards the end of Borromini's life and the upper part was not completed until after the architect's death.

Borromini devised the complex ground plan of the church from interlocking geometrical configurations, a typical Borromini device for constructing plans. The resulting effect is that the interior lower walls appear to weave in and out, partly alluding to a cross form, partly to a hexagonal form and partly to an oval form; geometrical figures that are all found explicitly in the dome above.[14][15] The area of the pendentives marks the transition from the lower wall order to the oval opening of the dome. Illuminated by windows hidden from a viewer below, interlocking octagons, crosses and hexagons diminish in size as the dome rises to a lantern with the symbol of the Trinity.

Oratory of Saint Philip Neri (Oratorio dei Filippini)

editIn the late sixteenth century, the Congregation of the Filippini (also known as the Oratorians) rebuilt the church of Santa Maria in Vallicella (known as the Chiesa Nuova -new church) in central Rome. In the 1620s, on a site adjacent to the church, the Fathers commissioned designs for their own residence and for an oratory (or oratorio in Italian) in which to hold their spiritual exercises. These exercises combined preaching and music in a form which became immensely popular and highly influential on the development of the musical oratorio.

The architect Paolo Maruscelli drew up plans for the site (which survive) and the sacristy was begun in 1629 and was in use by 1635. After a substantial benefaction in January 1637, however, Borromini was appointed as architect.[16] By 1640, the oratory was in use, a taller and richer clock tower was accepted, and by 1643, the relocated library was complete. The striking brick curved façade adjacent to the church entrance has an unusual pediment and does not entirely correspond to the oratory room behind it. The white oratory interior has a ribbed vault and a complex wall arrangement of engaged pilasters along with freestanding columns supporting first-level balconies. The altar wall was substantially reworked at a later date.

Borromini's relations with the Oratorians were often fraught; there were heated arguments over the design and the selection of building materials. By 1650, the situation came to a head and in 1652 the Oratorians appointed another architect.

However, with the help of his Oratorian friend and provost Virgilio Spada, Borromini documented his own account of the building of the oratory and the residence and an illustrated version was published in Italian in 1725 [17]

Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza

editFrom 1640 to 1650, he worked on the design of the church of Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza and its courtyard, near University of Rome La Sapienza palace. It was initially the church of the Roman Archiginnasio. He had been initially recommended for the commission in 1632, by his then-supervisor for the work at the Palazzo Barberini, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The site, like many in cramped Rome, is challenged by external perspectives. It was built at the end of Giacomo della Porta's long courtyard. The dome and cochlear steeple are peculiar, and reflect the idiosyncratic architectural motifs that distinguish Borromini from contemporaries. Inside, the nave has an unusual centralized plan circled by alternating concave and convex-ending cornices, leading to a dome decorated with linear arrays of stars and putti. The geometry of the structure is a symmetric six-pointed star; from the centre of the floor, the cornice looks like two equilateral triangles forming a hexagon, but three of the points are clover-like, while the other three are concavely clipped. The innermost columns are points on a circle. The fusion of feverish and dynamic baroque excesses with rationalistic geometry is an excellent match for a church in a papal institution of higher learning.

Sant'Agnese in Agone

editBorromini was one of several architects involved in the building of the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in Rome. Not only were some of his design intentions changed by succeeding architects but the net result is a building which reflects, rather unhappily, a mix of different approaches.

The decision to rebuild the church was taken in 1652 as part of Pope Innocent X's project to enhance the Piazza Navona, the urban space onto which his family palace, the Palazzo Pamphili, faced. The first plans for a Greek Cross church were drawn up by Girolamo Rainaldi and his son Carlo Rainaldi, who relocated the main entrance from the Via di Santa Maria dell'Anima to the Piazza Navona. The foundations were laid and much of the lower level walls had been constructed when the Rainaldis were dismissed due to criticisms of the design and Borromini was appointed in their stead.[18]

Borromini began a much more innovative approach to the façade which was expanded to include parts of the adjacent Palazzo Pamphili and gain space for his two bell towers.[19] Construction of the façade proceeded up to the cornice level and the dome completed as far as the lantern. On the interior, he placed columns against the piers of the lower order which was mainly completed.

In 1655, Innocent X died and the project lost momentum. In 1657, Borromini resigned and Carlo Rainaldi was recalled who made a number of significant changes to Borromini's design. Further alterations were made by Bernini including the façade pediment. In 1668, Carlo Rainaldi returned as architect and Ciro Ferri received the commission to fresco the dome interior which it is highly unlikely that Borromini intended. Further large-scale statuary and coloured marbling were also added; again, these are not part of Borromini's design repertoire which was orientated to white stucco architectural and symbolic motifs.[20]

The Re Magi Chapel of the Propaganda Fide

editThe College of the Propagation of the Faith or Propaganda Fide in Rome includes the Re Magi Chapel by Borromini, generally considered by architectural historians to be one of his most spatially unified architectural interiors.[21]

The chapel replaced a small oval chapel designed by his rival Bernini and was a late work in Borromini's career; he was appointed as architect in 1648 but it was not until 1660 that construction of the chapel began and although the main body of work was completed by 1665, some of the decoration was finished after his death.

His façade to the Via di Propaganda Fide comprises seven bays articulated by giant pilasters. The central bay is a concave curve and accommodates the main entry into the college courtyard and complex, with the entrance to the chapel to the left and to the college to the right.

Other works

editBorromini's works include:

- Interior of Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano

- Cappella Spada, San Girolamo della Carità (uncertain attribution)

- Palazzo Spada (trick perspective)

- Palazzo Barberini (upper-level windows and oval staircase)

- Santi Apostoli, Naples - Filamarino Altar

- Sant'Andrea delle Fratte

- Oratorio dei Filippini

- Palazzo Carpegna, Rome (ground floor portico and portal, helicoidal ramp leading to the upper floors)

- Collegio de Propaganda Fide[22]

- Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori, Rome

- Santa Maria alla Porta, Milan - portal and tympanum

- San Giovanni in Oleo (restoration)

- Palazzo Giustiniani (with Carlo Fontana)

- Façade and loggia Palazzo Falconieri

- Santa Lucia in Selci (restoration)

- Saint Peter's Basilica (gates to Blessed Sacrament Chapel and possibly parts of baldacchino)

Death and epitaph

editIn the summer of 1667, and following the completion of the Falconieri chapel (the High Altar chapel) in San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, Borromini committed suicide in Rome by drawing his sword, resting the hilt against his bed, and falling on it "with such force that it ran into [his] body, from one side to the other"[23] This was possibly as a result of nervous disorders and depression. The architect named cardinal Ulderico Carpegna executor of his will and bequeathed him money and objects of considerable value "for", as he wrote, "the infinite debt I have toward him".[24] The prelate was a former patron who had commissioned Borromini important works of transformation and expansion of his palace at Fontana di Trevi. In his testament, Borromini wrote that he did not want any name on his burial and expressed the desire to be buried in the tomb of his kinsman Carlo Maderno in San Giovanni dei Fiorentini.

In recent times (in 1955), his name was added to the marble plaque below the tomb of Maderno and a commemorative plaque commissioned by the Swiss embassy in Rome was placed on a pillar of the church. This Latin inscription reads:

FRANCISCVS BORROMINI TICINENSIS

EQVES CHRISTI

QVI

IMPERITVRAE MEMORIAE ARCHITECTVS

DIVINAM ARTIS SVAE VIM

AD ROMAM MAGNIFICIS AEDIFICIIS EXORNANDAM VERTIT

IN QVIBUS

ORATORIVM PHILIPPINVM S. IVO S. AGNES IN AGONE

INSTAVRATA LATERANENSIS ARCHIBASILICA

S. ANDREAS DELLE FRATTE NVNCVPATUM

S. CAROLVS IN QVIRINALI

AEDES DE PROPAGANDA FIDE

HOC AVTEM IPSVM TEMPLVM

ARA MAXIMA DECORAVIT

NON LONGE AB HOC LAPIDE

PROPE MORTALES CAROLI MADERNI EXUVVIAS

PROPINQVI MVNICIPIS ET AEMVLI SVI

IN PACE DOMINI QVIESCIT

The adjective "Ticinensis" used in the plaque is an anachronism, since the name, related to the Ticino river, was chosen only in 1803, when the modern Canton was created by Napoleon.[26]

Honours

edit- Francesco Borromini was featured on the obverse of the 6th series 100 Swiss Franc banknote, which was in circulation from 1976 until 2000.[27]

This decision at that time caused polemics in Switzerland, started by the Swiss-Italian art historian Piero Bianconi. According to him, since in 17th century the territories which in 1803 became the Canton Ticino were Italian possessions of some Swiss cantons (Condominiums of the Twelve Cantons), Borromini could neither be defined Ticinese nor Swiss.[26][28] The architect was also featured on the 7th series, which was a reserve emission and was never released. The reverse of both series shows architectural details from some of his major works.

- He is the subject of the film La Sapienza by Eugène Green released in 2015.

References

edit- ^ "Borromini, Francesco". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09.

- ^ Peter Stein. "Borromini, Francesco." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 25 Jul. 2013. <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010190>

- ^ "Francesco Borromini." Encyclopædia Britannica. Web. 30 Oct. 2010.

- ^ "Symposia Melitensia" (PDF). University of Malta Junior College. September 2017. ISSN 1812-7509.

- ^ Wieland, Martin; Gorraiz, Juan (28 May 2020). "The rivalry between Bernini and Borromini from a scientometric perspective". Scientometrics. 125 (2): 1643–1663. doi:10.1007/s11192-020-03514-5. ISSN 1588-2861. S2CID 214747325.

- ^ Blunt, Anthony (1979), Borromini, Harvard University Press, Belknap, p. 21

- ^ Blunt,(1979), p. 213-7

- ^ Later he was also nicknamed "Bissone".

- ^ He moved to Milano between 1608 and 1614. Carboneri, Nino. "Francesco Borromini". Dizionario biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ Blunt, Anthony. Borromini, Belknap Harvard, 1979, p. 13

- ^ As Siegfried Giedion pointed out in Space, Time and Architecture (1941 etc.)

- ^ "Plan of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane". Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2006-01-02.

- ^ "S. Carlo alle Quattro Fontane".

- ^ Steinberg L. San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. A Study in Multiple Form and Architectural Symbolism. New York 1977, p 117 and Fig. 85. The effect has been noted by others that he "designed the walls to weave in and out as if they were formed not of stone but of pliant substance set in motion by an energetic space, carrying with them the deep entablatures, the cornices, mouldings and pediments" (Trachtenberg & Hyman)

- ^ "San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane". Archived from the original on 2009-04-08. Retrieved 2006-01-02.

- ^ See Connors J., Borromini and the Roman Oratory: Style and Society, New York, London & Cambridge (Massachusetts), 1980, and Kerry Downes, Averlo format perfettamente: Borromini's first two years at the Roman Oratory, Architectural History, 57 (2012), pp. 109-39.

- ^ For an English translation of the 1725 edition and discussion of the architecture see Kerry Downes, Borromini's Book, Oblong Creative, 2010

- ^ Blunt A. Borromini, Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1979, 157

- ^ Each of the constructed bell towers has a clock, one for Roman time, the other for tempo ultramontano or European time

- ^ Blunt, 1979,159-160

- ^ See, Magnuson, T. Rome in the Age of Bernini, Vol 2, 207

- ^ "Collegio di Propaganda Fide".

- ^ "Borromini's suicide". Archived from the original on 2018-05-07.

- ^ Salvagni, Isabella. Palazzo Carpegna, 1577-1934. Rome: Edizioni De Luca, 2000, 230 pp., 117 ill., 70 in color

- ^ Francesco Borromini from the Ticino

Knight of Christ

who

is an architect with an eternal reputation

divine in the strength of his art

who applied himself to the adornment of the magnificent buildings of Rome

among which are

the Oratory of the Filippini, S. Ivo, S. Agnese in Agone

reworking the Lateran archbasilica

S. Andrea delle Fratte

S. Carlo on the Quirinal Hill

the temple building of the Propaganda Fide

and also in this temple (S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini)

he decorated the High Altar

not far from this grave stone

near to the mortal remains of Carlo Maderno he was found

near to the city and his relative (Carlo Maderno)

in peace he rests with the Lord. - ^ a b De Bernardis, Edy (June 2006). Bettosini, Luca (ed.). "Il Boccalino" [The little wine jug]. La Terra Racconta (in Italian) (34). Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "Sixth banknote series, 1984".

- ^ About the concept of Italian Switzerland and the formation of a Swiss Italian identity around the centuries, please see: Ariele Morinini (2021). "Il nome e la lingua - Studi e documenti di storia linguistica svizzero-italiana" (PDF). Romanica Helvetica (in Italian). 142. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag: passim. ISBN 978-3-7720-8730-1. (Print), (ePDF), (ePub). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-25.

External links

edit- A map giving the location of Borromini's buildings in Rome

- Architectural drawings by Borrominis in der Albertina

- Columbia University: Joseph Connors, Francesco Borromini: Opus Architectonicum, Milan, 1998: Introduction to Borromini's own description of the Casa dei Filippini

- Borromini's own account of his suicide

- Marvin Trachtenberg and Isabelle Hyman. Architecture: from Prehistory to Post-Modernism. pp. 346–7.

- Borromini: rare interior color images