First Council of Constantinople

The First Council of Constantinople (Latin: Concilium Constantinopolitanum; Greek: Σύνοδος τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in AD 381 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I.[1][2] This second ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom, except for the Western Church,[3] confirmed the Nicene Creed, expanding the doctrine thereof to produce the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, and dealt with sundry other matters. It met from May to July 381[4] in the Church of Hagia Irene and was affirmed as ecumenical in 451 at the Council of Chalcedon.

| First Council of Constantinople | |

|---|---|

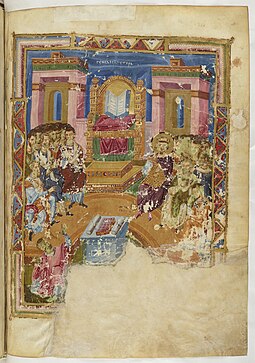

9th century Byzantine manuscript illumination of I Constantinople. Homilies of St. Gregory of Nazianzus, 879–883. | |

| Date | 381 |

| Accepted by | |

Previous council | First Council of Nicaea |

Next council | Council of Ephesus |

| Convoked by | Emperor Theodosius I |

| President | Timothy of Alexandria, Meletius of Antioch, Gregory Nazianzus, and Nectarius of Constantinople |

| Attendance | 150 (no representation of Western Church) |

| Topics | Arianism, Holy Spirit |

Documents and statements | Nicene Creed of 381, seven canons (three disputed) |

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

Background

editWhen Theodosius ascended to the imperial throne in 380, he began on a campaign to bring the Eastern Church back to Nicene Christianity. Theodosius wanted to further unify the entire empire behind the orthodox position and decided to convene a church council to resolve matters of faith and discipline.[5]: 45 Gregory Nazianzus was of similar mind, wishing to unify Christianity. In the spring of 381 they convened the second ecumenical council in Constantinople.

Theological context

editThe Council of Nicaea in 325 had not ended the Arian controversy which it had been called to clarify. Arius and his sympathizers, e.g. Eusebius of Nicomedia were admitted back into the church after ostensibly accepting the Nicene creed. Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, the most vocal opponent of Arianism, was ultimately exiled through the machinations of Eusebius of Nicomedia. After the death of Constantine I in 337 and the accession of his Arian-leaning son Constantius II, open discussion of replacing the Nicene creed itself began. Up until about 360, theological debates mainly dealt with the divinity of the Son, the second person of the Trinity. However, because the Council of Nicaea had not clarified the divinity of the Holy Spirit, the third person of the Trinity, it became a topic of debate. The Macedonians denied the divinity of the Holy Spirit. This was also known as Pneumatomachianism.

Nicene Christianity also had its defenders: apart from Athanasius, the Cappadocian Fathers' Trinitarian discourse was influential in the council at Constantinople. Apollinaris of Laodicea, another pro-Nicene theologian, proved controversial. Possibly in an over-reaction to Arianism and its teaching that Christ was not God, he taught that Christ consisted of a human body and a divine mind, rejecting the belief that Christ had a complete human nature, including a human mind.[6] He was charged with confounding the persons of the Godhead, and with giving in to the heretical ways of Sabellius. Basil of Caesarea accused him of abandoning the literal sense of the scripture, and taking up wholly with the allegorical sense. His views were condemned in a Synod at Alexandria, under Athanasius of Alexandria, in 362, and later subdivided into several different heresies, the main ones of which were the Polemians and the Antidicomarianites.

Geopolitical context

editTheodosius' strong commitment to Nicene Christianity involved a calculated risk because Constantinople, the imperial capital of the Eastern Empire, was solidly Arian. To complicate matters, the two leading factions of Nicene Christianity in the East, the Alexandrians and the supporters of Meletius in Antioch, were "bitterly divided ... almost to the point of complete animosity".[7]

The bishops of Alexandria and Rome had worked over a number of years to keep the see of Constantinople from stabilizing. Thus, when Gregory was selected as a candidate for the bishopric of Constantinople, both Alexandria and Rome opposed him because of his Antiochene background.[citation needed]

Meletian schism

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2011) |

See of Constantinople

editThe incumbent bishop of Constantinople was Demophilus, a Homoian Arian. On his accession to the imperial throne, Theodosius offered to confirm Demophilus as bishop of the imperial city on the condition of accepting the Nicene Creed; however, Demophilus refused to abandon his Arian beliefs, and was immediately ordered to give up his churches and leave Constantinople.[8][9] After forty years under the control of Arian bishops, the churches of Constantinople were now restored to those who subscribed to the Nicene Creed; Arians were also ejected from the churches of other cities in the Eastern Roman Empire thus re-establishing Christian orthodoxy in the East.[10]

There ensued a contest to control the newly recovered see. A group led by Maximus the Cynic gained the support of Patriarch Peter of Alexandria by playing on his jealousy of the newly created see of Constantinople. They conceived a plan to install a cleric subservient to Peter as bishop of Constantinople so that Alexandria would retain the leadership of the Eastern Churches.[11] Many commentators characterize Maximus as having been proud, arrogant and ambitious. However, it is not clear the extent to which Maximus sought this position due to his own ambition or if he was merely a pawn in the power struggle.[citation needed] In any event, the plot was set into motion when, on a night when Gregory was confined by illness, the conspirators burst into the cathedral and commenced the consecration of Maximus as bishop of Constantinople. They had seated Maximus on the archiepiscopal throne and had just begun shearing away his long curls when the day dawned. The news of what was transpiring quickly spread and everybody rushed to the church. The magistrates appeared with their officers; Maximus and his consecrators were driven from the cathedral, and ultimately completed the tonsure in the tenement of a flute-player.[12]

The news of the brazen attempt to usurp the episcopal throne aroused the anger of the local populace among whom Gregory was popular. Maximus withdrew to Thessalonica to lay his cause before the emperor but met with a cold reception there. Theodosius committed the matter to Ascholius, the much respected bishop of Thessalonica, charging him to seek the counsel of Pope Damasus I.[13]

Damasus' response repudiated Maximus summarily and advised Theodosius to summon a council of bishops for the purpose of settling various church issues such as the schism in Antioch and the consecration of a proper bishop for the see of Constantinople.[14] Damasus condemned the translation of bishops from one see to another and urged Theodosius to "take care that a bishop who is above reproach is chosen for that see."[15]

Proceedings

editThirty-six Pneumatomachians arrived but were denied admission to the council when they refused to accept the Nicene creed.

Since Peter, the Pope of Alexandria, was not present, the presidency over the council was given to Meletius as Patriarch of Antioch.[16] The first order of business before the council was to declare the clandestine consecration of Maximus invalid, and to confirm Theodosius' installation of Gregory Nazianzus as Archbishop of Constantinople. When Meletius died shortly after the opening of the council, Gregory was selected to lead the council.

The Egyptian and Macedonian bishops who had supported Maximus's ordination arrived late for the council. Once there, they refused to recognise Gregory's position as head of the church of Constantinople, arguing that his transfer from the See of Sasima was canonically illegitimate because one of the canons of the Council of Nicaea had forbidden bishops to transfer from their sees.[17]: 358–9

McGuckin describes Gregory as physically exhausted and worried that he was losing the confidence of the bishops and the emperor.[17]: 359 Ayres goes further and asserts that Gregory quickly made himself unpopular among the bishops by supporting the losing candidate for the bishopric of Antioch and vehemently opposing any compromise with the Homoiousians.[18]: 254

Rather than press his case and risk further division, Gregory decided to resign his office: "Let me be as the Prophet Jonah! I was responsible for the storm, but I would sacrifice myself for the salvation of the ship. Seize me and throw me... I was not happy when I ascended the throne, and gladly would I descend it."[19] He shocked the council with his surprise resignation and then delivered a dramatic speech to Theodosius asking to be released from his offices. The emperor, moved by his words, applauded, commended his labor, and granted his resignation. The council asked him to appear once more for a farewell ritual and celebratory orations. Gregory used this occasion to deliver a final address (Or. 42) and then departed.[17]: 361

Nectarius, an unbaptized civil official, was chosen to succeed Gregory as president of the council.[18]: 255

Canons

editSeven canons, four of these doctrinal canons and three disciplinary canons, are attributed to the council and accepted by both the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches; the Roman Catholic Church accepts only the first four[20] because only the first four appear in the oldest copies and there is evidence that the last three were later additions.[21]

- The first canon is an important dogmatic condemnation of all shades of Arianism, and also of Macedonianism and Apollinarianism.[20]

- The second canon renewed the Nicene legislation imposing upon the bishops the observance of diocesan and patriarchal limits.[20]

- The third canon reads:

The Bishop of Constantinople, however, shall have the prerogative of honour after the Bishop of Rome because Constantinople is New Rome.[22][21][20]

- The fourth canon decreed the consecration of Maximus as Bishop of Constantinople to be invalid, declaring "that [Maximus] neither was nor is a bishop, nor are they who have been ordained by him in any rank of the clergy".[20][23] This canon was directed not only against Maximus, but also against the Egyptian bishops who had conspired to consecrate him clandestinely at Constantinople, and against any subordinate ecclesiastics that he might have ordained in Egypt.[24]

- The fifth canon might actually have been passed the next year, 382, and is in regard to a Tome of the Western bishops, perhaps that of Pope Damasus I.[20]

- The sixth canon might belong to the year 382 as well and was subsequently passed at the Quinisext Council as canon 95. It limits the ability to accuse bishops of wrongdoing.[20]

- The seventh canon regards procedures for receiving certain heretics into the church.[20]

Dispute concerning the third canon

editThe third canon was a first step in the rising importance of the new imperial capital, just fifty years old, and was notable in that it demoted the patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria. Jerusalem, as the site of the first church, retained its place of honor. It originally did not elicit controversy, as the Papal legate Paschasinus and a partisan of his, Diogenes of Cyzicus, reference the canon as being in force during the first session of the Council of Chalcedon.[25] According to Eusebius of Dorlyeum, another Papal ally during Chalcedon, "I myself read this very canon [Canon 3] to the most holy pope in Rome in the presence of the clerics of Constantinople and he accepted it."[26]

Nevertheless, controversy has ensued since then. The status of the canon became questioned after disputes over Canon 28 of the Council of Chalcedon erupted. Pope Leo the Great,[27] declared that this canon had never been submitted to Rome and that their lessened honor was a violation of the Nicene council order. Throughout the next several centuries, the Western Church asserted that the Bishop of Rome had supreme authority, and by the time of the Great Schism the Roman Catholic Church based its claim to supremacy on the succession of St. Peter. At the Fourth Council of Constantinople (869), the Roman legates[28] asserted the place of the bishop of Rome's honor over the bishop of Constantinople's. After the Great Schism of 1054, in 1215 the Fourth Lateran Council declared, in its fifth canon, that the Roman Church "by the will of God holds over all others pre-eminence of ordinary power as the mother and mistress of all the faithful".[29][30] Roman supremacy over the whole world was formally claimed by the new Latin patriarch. The Roman correctores of Gratian,[31] insert the words: "canon hic ex iis est quos apostolica Romana sedes a principio et longo post tempore non recipit" ("this canon is one of those that the Apostolic See of Rome has not accepted from the beginning and ever since").[citation needed]

Later on, Baronius asserted that the third canon was not authentic, not in fact decreed by the council. Contrarily, roughly contemporaneous Greeks maintained that it did not declare supremacy of the Bishop of Rome, but the primacy; "the first among equals", similar to how they today view the Bishop of Constantinople.[citation needed]

Aftermath

editIt has been asserted by many that a synod was held by Pope Damasus I in the following year (382) which opposed the disciplinary canons of the Council of Constantinople, especially the third canon which placed Constantinople above Alexandria and Antioch. The synod protested against this raising of the bishop of the new imperial capital, just fifty years old, to a status higher than that of the bishops of Alexandria and Antioch, and stated that the primacy of the Roman see had not been established by a gathering of bishops but rather by Christ himself.[32][33][note 1] Thomas Shahan says that, according to Photius too, Pope Damasus approved the council, but he adds that, if any part of the council were approved by this pope, it could have been only its revision of the Nicene Creed, as was the case also when Gregory the Great recognized it as one of the four general councils, but only in its dogmatic utterances.[35]

Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed

editTraditionally, the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed has been associated with the Council of Constantinople (381). It is roughly theologically equivalent to the Nicene Creed, but includes two additional articles: an article on the Holy Spirit—describing Him as "the Lord, the Giver of Life, Who proceeds from the Father, Who with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified, and Who spoke through the prophets"—and an article about the church, baptism, and the resurrection of the dead. (For the full text of both creeds, see Comparison between Creed of 325 and Creed of 381.)

However, scholars are not agreed on the connection between the Council of Constantinople and the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed. Some modern scholars believe that this creed, or something close to it, was stated by the bishops at Constantinople, but not promulgated as an official act of the council. Scholars also dispute whether this creed was simply an expansion of the Creed of Nicaea, or whether it was an expansion of another traditional creed similar but not identical to the one from Nicaea.[36] In 451, the Council of Chalcedon referred to this creed as "the creed ... of the 150 saintly fathers assembled in Constantinople",[37] indicating that this creed was associated with Constantinople (381) no later than 451.

Christology

editThis council condemned Arianism which began to die out with further condemnations at a council of Aquileia by Ambrose of Milan in 381. With the discussion of Trinitarian doctrine now developed, the focus of discussion changed to Christology, which would be the topic of the Council of Ephesus of 431 and the Council of Chalcedon of 451.

Shift of influence from Rome to Constantinople

editDavid Eastman cites the First Council of Constantinople as another example of the waning influence of Rome over the East. He notes that all three of the presiding bishops came from the East. Damasus had considered both Meletius and Gregory to be illegitimate bishops of their respective sees and yet, as Eastman and others point out, the Eastern bishops paid no heed to his opinions in this regard.[38]

The First Council of Constantinople (381) was the first appearance of the term 'New Rome' in connection to Constantinople. The term was employed as the grounds for giving the relatively young church of Constantinople precedence over Alexandria and Antioch ('because it is the New Rome').

Liturgical commemorations

editThe 150 individuals at the council are commemorated in the Calendar of saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church on February 17.

The Eastern Orthodox Church in some places (e.g. Russia) has a feast day for the Fathers of the First Six Ecumenical Councils on the Sunday nearest to July 13[39] and on May 22.[citation needed]

Notes

edit- ^ In opposition to this view, Francis Dvornik asserts that not only did Damasus offer "no protest against the elevation of Constantinople", that change in the primacy of the major sees was effected in an "altogether friendly atmosphere." According to Dvornik, "Everyone continued to regard the Bishop of Rome as the first bishop of the Empire, and the head of the church."[34]

References

edit- ^ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 5, chapters 8 & 11, puts the council in the same year as the revolt of Magnus Maximus and death of Gratian.

- ^ Hebblewhite, M. (2020). Theodosius and the Limits of Empire. pp. 56ff.

- ^ Richard Kieckhefer (1989). "Papacy". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-684-18275-0.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: First Council of Constantinople". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ Ruether, Rosemary Radford (1969), Gregory of Nazianzus: Rhetor and Philosopher, Oxford University Press

- ^ McGrath, Alister (1998). "The Patristic Period". Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20843-7.

- ^ McGuckin, p. 235

- ^ Onslow 1911 cites Socr. H. E. v. 7.

- ^ Alban Butler (May 2006). The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints; Compiled from Original Monuments, and Other Authentic Records. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-1-4286-1025-5. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Onslow 1911.

- ^ The Church standard. Walter N. Hering. 1906. pp. 125–. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ McGuckin p. 318

- ^ Venables 1911 cites Migne, Patrologia Latina xiii. pp. 366–369; Epp. 5, 5, 6.

- ^ Christopher Wordsworth (bp. of Lincoln.) (1882). A Church history. Rivingtons. pp. 312–. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Joseph Marie Felix Marique (1962). Leaders of Iberean Christianity, 50–650 A.D. St. Paul Editions. p. 59. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles (1907). Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ a b c McGuckin

- ^ a b Lewis Ayres (3 May 2006). Nicaea and its legacy: an approach to fourth-century Trinitarian theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-875505-0. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ PG, 37.1157–9, Carm. de vita sua, ll 1828–55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "NPNF2-14. The Seven Ecumenical Councils". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 2005-06-01. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- ^ a b "NPNF2-14. First Council of Constantinople". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 2015-08-24.

- ^ "NPNF2-14. Canon III". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 2005-06-01. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Venables 1911 cites Philippe Labbe, Concilia, ii. 947, 954, 959.

- ^ Carl Ullmann (1851). Gregory of Nazianzum. Translated by Cox, G. V. pp. 241ff. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Richard Price and Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon Vol 1, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, p. 159

- ^ Richard Price and Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon Vol 3, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, p. 89

- ^ Ep. cvi in P.L., LIV, 1003, 1005.

- ^ J. D. Mansi, XVI, 174.

- ^ The Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215

- ^ J. D. Mansi, XXII, 991.

- ^ (1582), at dist. xxii, c. 3.

- ^ Henry Chadwick (2001). The church in ancient society: from Galilee to Gregory the Great. Oxford University Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-19-924695-3. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Nichols, Aidan (2010) [(T & T Clark) 1992]. Rome and the Eastern Churches. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1586172824. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Dvornik, Francis (1966). Byzantium and the Roman primacy. Fordham University Press. p. 47. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

Pope Damasus offered no protest against the elevation of Constantinople, even though Alexandria had always been, in the past, in close contact with Rome. This event, which has often been considered the first conflict between Rome and Byzantium, actually took place in an altogether friendly atmosphere. Everyone continued to regard the Bishop of Rome as the first bishop of the Empire, and the head of the church.

- ^ "Thomas Shahan, "First Council of Constantinople" in The Catholic Encyclopedia". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica". Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ Tanner, Norman; Alberigo, Giuseppe, eds. (1990). Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-87840-490-2.

- ^ David L. Eastman (2011). Paul the Martyr: The Cult of the Apostle in the Latin West. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-58983-515-3. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "Menaion – July 13" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

Works cited

edit- Onslow, P. (1911). . In Wace, Henry; Piercy, William C. (eds.). Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century (3rd ed.). London: John Murray.

- Venables, E. (1911). . In Wace, Henry; Piercy, William C. (eds.). Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century (3rd ed.). London: John Murray.

Further reading

edit- Giuseppe Alberigo, ed., Conciliorum Oecumenicoum Generaliumque Decreta, vol. 1 (Turnhout, 2006), pp. 35–70.

- Freeman, Charles (2009). AD 381: Heretics, Pagans and the Christian State. Pimlico. ISBN 978-1-84595-007-1.

- Hebblewhite, Mark (2020). Theodosius and the Limits of Empire. Routledge.

- McGuckin, John Anthony (2001). St. Gregory of Nazianzus: An Intellectual Biography. Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 0-88141-229-5. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Kelly, John N. D. (2006) [1972]. Early Christian Creeds (3rd ed.). London-New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0826492166.

- Ritter, Adolf Martin (1965). Das Konzil von Konstantinopel und sein Symbol: Studien zur Geschichte und Theologie des II. Ökumenischen Konzils. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.