James Madison as Father of the Constitution

James Madison (March 16, 1751[b] – June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the 4th president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. He is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights. Disillusioned by the weak national government established by the Articles of Confederation, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution. Madison's Virginia Plan served as the basis for the Constitutional Convention's deliberations, and he was one of the most influential individuals at the convention. He became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution, and he joined with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays that was one of the most influential works of political science in American history.

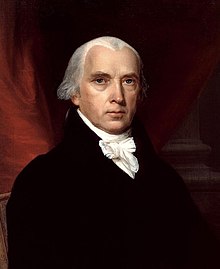

James Madison | |

|---|---|

Portrait by John Vanderlyn, 1816 | |

| 4th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| 5th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office May 2, 1801 – March 3, 1809 | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia | |

| In office March 4, 1789 – March 4, 1797 | |

| Delegate from Virginia to the Congress of the Confederation | |

| In office November 6, 1786 – October 30, 1787 | |

| In office March 1, 1781 – November 1, 1783 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 16, 1751 Port Conway, Virginia, British America |

| Died | June 28, 1836 (aged 85) Montpelier, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic–Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Parents |

|

Background and calling for a convention

editAs a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, Madison continued to advocate for religious freedom, and, along with Jefferson, drafted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. That amendment, which guaranteed freedom of religion and disestablished the Church of England, was passed in 1786.[1] Madison also became a land speculator, purchasing land along the Mohawk River in a partnership with another Jefferson protege, James Monroe.[2]

Throughout the 1780s, Madison advocated for reform of the Articles of Confederation. He became increasingly worried about the disunity of the states and the weakness of the central government after the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783.[3] He believed that "excessive democracy" caused social decay, and was particularly troubled by laws that legalized paper money and denied diplomatic immunity to ambassadors from other countries.[4] He was also concerned about the inability of Congress to capably conduct foreign policy, protect American trade, and foster the settlement of the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River.[5] As Madison wrote, "a crisis had arrived which was to decide whether the American experiment was to be a blessing to the world, or to blast for ever the hopes which the republican cause had inspired."[6] He committed to an intense study of law and political theory and also was heavily influenced by Continental Enlightenment texts sent by Jefferson from France.[7] He especially sought out works on international law and the constitutions of "ancient and modern confederacies" such as the Dutch Republic, the Swiss Confederation, and the Achaean League.[8] He came to believe that the United States could improve upon past republican experiments by its size; with so many distinct interests competing against each other, Madison hoped to minimize the abuses of majority rule.[9] Additionally, navigation rights to the Mississippi River highly concerned Madison. He disdained a proposal by John Jay that the United States acquiesce claims to the river for 25 years, and, according to historian John Ketcham, his desire to fight the proposal played a major role in motivating Madison to return to Congress in 1787.[10]

Madison helped arrange the 1785 Mount Vernon Conference, which settled disputes regarding navigation rights on the Potomac River and also served as a model for future interstate conferences.[11] At the 1786 Annapolis Convention, he joined with Hamilton and other delegates in calling for another convention to consider amending the Articles.[12] After winning the election to another term in Congress, Madison helped convince the other Congressmen to authorize the Philadelphia Convention to propose amendments.[13] Though many members of Congress were wary of the changes the convention might bring, nearly all agreed that the existing government needed some sort of reform.[14] Madison ensured that General Washington, who was popular throughout the country, and Robert Morris, who was influential in the casting the critical vote of the state of Pennsylvania, would both broadly support Madison's plan to implement a new constitution.[15] The outbreak of Shays' Rebellion in 1786 reinforced the necessity for constitutional reform in the eyes of Washington and other American leaders.[16][17]

The Philadelphia Convention and the Virginia Plan

editof the U.S. Constitution

Before a quorum was reached at the Philadelphia Convention on May 25, 1787,[19] Madison worked with other members of the Virginia delegation, especially Edmund Randolph and George Mason, to create and present the Virginia Plan.[20] This Plan was an outline for a new federal constitution; it called for three branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial), a bicameral Congress (consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives) apportioned by population, and a federal Council of Revision that would have the right to veto laws passed by Congress. Reflecting the centralization of power envisioned by Madison, the Virginia Plan granted the Senate the power to overturn any law passed by state governments.[21] The Virginia Plan did not explicitly lay out the structure of the executive branch, but Madison himself favored a single executive.[22] Many delegates were surprised to learn that the plan called for the abrogation of the Articles and the creation of a new constitution, to be ratified by special conventions in each state rather than by the state legislatures. With the assent of prominent attendees such as Washington and Benjamin Franklin, the delegates went into a secret session to consider a new constitution.[23]

Though the Virginia Plan was extensively changed during the debate and presented as an outline rather than a draft of a possible constitution, its use at the convention has led many to call Madison the "Father of the Constitution".[24] Madison spoke over 200 times during the convention, and his fellow delegates held him in high esteem. Delegate William Pierce wrote that "in the management of every great question he evidently took the lead in the Convention [...] he always comes forward as the best informed man of any point in debate."[25] Madison believed that the constitution produced by the convention "would decide for ever the fate of republican government" throughout the world, and he kept copious notes to serve as a historical record of the convention.[26]

In crafting the Virginia Plan, Madison looked to develop a system of government that adequately prevented the rise of factions believing that a Constitutional Republic would be most fitting to do so. Madison's definition of faction was similar to that of the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume. Madison borrowed from Hume's definition of a faction when describing the dangers they impose upon the American Republic.[27] In the essay Federalist No. 10 Madison described a faction as a "number of citizens [...] who are united by a common impulse of passion or interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or permanent and aggregate interest of the community".[28] Madison drew further influence from the Scottish Economist Adam Smith who believed that every civilized society developed into economic factions based on the different interests of individuals. Madison, throughout his writing, alluded to The Wealth of Nations on multiple occasions as he advocated for a free system of commerce among the states that he believed would be beneficial to society.[29]

Madison had hoped that a coalition of Southern states and populous Northern states would ensure the approval of a constitution largely similar to the one proposed in the Virginia Plan. However, delegates from small states successfully argued for more power for state governments and presented the New Jersey Plan as an alternative. In response, Roger Sherman proposed the Connecticut Compromise, which sought to balance the interests of small and large states. During the convention, Madison's Council of Revision was not used, and each state was given equal representation in the Senate, and the state legislatures, rather than the House of Representatives, were given the power to elect members of the Senate. Madison convinced his fellow delegates to have the Constitution ratified by ratifying conventions rather than state legislatures, which he distrusted. He also helped ensure that the president would have the ability to veto federal laws and would be elected independently of Congress through the Electoral College. By the end of the convention, Madison believed that the new constitution failed to give enough power to the federal government compared to the state governments, but he still viewed the document as an improvement on the Articles of Confederation.[30]

The ultimate question before the convention, historian Gordon Wood notes, was not how to design a government but whether the states should remain sovereign, whether sovereignty should be transferred to the national government, or whether the constitution should settle somewhere in between.[31] Most of the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention wanted to empower the federal government to raise revenue and protect property rights.[32] Those who, like Madison, thought democracy in the state legislatures was excessively subjective, wanted sovereignty transferred to the national government, while those who did not think this a problem wanted to retain the model of the Articles of Confederation. Even many delegates who shared Madison's goal of strengthening the central government reacted strongly against the extreme change to the status quo envisioned in the Virginia Plan. Though Madison lost most of his debates and discussions over how to amend the Virginia Plan, in the process, however, he increasingly shifted the debate away from a position of pure state sovereignty. Since most disagreements over what to include in the constitution were ultimately disputes over the balance of sovereignty between the states and national government, Madison's influence was critical. Wood notes that Madison's ultimate contribution was not in designing any particular constitutional framework, but in shifting the debate toward a compromise of "shared sovereignty" between the national and state governments.[31][33]

The Federalist Papers and ratification debates

editAfter the Philadelphia Convention ended in September 1787, Madison convinced his fellow congressmen to remain neutral in the ratification debate and allow each state to vote upon the Constitution.[34] Throughout the United States, opponents of the Constitution, known as Anti-Federalists, began a public campaign against ratification. In response, Hamilton and Jay began publishing a series of pro-ratification newspaper articles in New York.[35] After Jay dropped out from the project, Hamilton approached Madison, who was in New York on congressional business, to write some of the essays.[36] Altogether, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay wrote the 85 essays of what became known as The Federalist Papers in six months, with Madison writing 29 of the essays. The Federalist Papers successfully defended the new Constitution and argued for its ratification to the people of New York. The articles were also published in book form and became a virtual debater's handbook for the supporters of the Constitution in the ratifying conventions. Historian Clinton Rossiter called The Federalist Papers "the most important work in political science that ever has been written, or is likely ever to be written, in the United States".[37] Federalist No. 10, Madison's first contribution to The Federalist Papers, became highly regarded in the 20th century for its advocacy of representative democracy.[38] In Federalist 10, Madison describes the dangers posed by factions and argues that their negative effects can be limited through the formation of a large republic. He states that in large republics the significant sum of factions that emerge will successfully dull the effects of others.[39] In Federalist No. 51, he goes on to explain how the separation of powers between three branches of the federal government, as well as between state governments and the federal government, established a system of checks and balances that ensured that no one institution would become too powerful.[40]

While Madison and Hamilton continued to write The Federalist Papers, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and several smaller states voted to ratify the Constitution.[41] After finishing his last contributions to The Federalist Papers, Madison returned to Virginia.[42] Initially, Madison did not want to stand for election to the Virginia Ratifying Convention, but he was persuaded to do so by the strength of the Anti-Federalists.[43] Virginians were divided into three main camps: Washington and Madison led the faction in favor of ratification of the Constitution, Randolph and Mason headed a faction that wanted ratification but also sought amendments to the Constitution, and Patrick Henry was the most prominent member of the faction opposed to the ratification of the Constitution.[44] When the Virginia Ratifying Convention began on June 2, 1788, the Constitution had been ratified by eight of the required nine states. New York, the second-largest state and a bastion of anti-federalism would likely not ratify it without the stated commitment of Virginia, and in the event of Virginia's failure to join the new government there would be the disquieting disqualification of George Washington from being the first president.[43]

At the start of the convention in Virginia, Madison knew that most delegates had already made up their minds, and he focused his efforts on winning the support of the relatively small number of undecided delegates.[45] His long correspondence with Randolph paid off at the convention as Randolph announced that he would support unconditional ratification of the Constitution, with amendments to be proposed after ratification.[46] Though Henry gave several persuasive speeches arguing against ratification, Madison's expertise on the subject he had long argued for allowed him to respond with rational arguments to Henry's emotional appeals.[47] In his final speech to the ratifying convention, Madison implored his fellow delegates to ratify the Constitution as it had been written, arguing that the failure to do so would lead to the collapse of the entire ratification effort as each state would seek favorable amendments.[48] On June 25, 1788, the convention voted 89–79 to ratify the Constitution, making Virginia the tenth state to do so.[49] New York ratified the constitution the following month, and Washington won the country's first presidential election.

The Bill of Rights

editAnticipating amendments

editThe 1st United States Congress, which met in New York City's Federal Hall, was a triumph for the Federalists. The Senate of eleven states contained 20 Federalists with only two Anti-Federalists, both from Virginia. The House included 48 Federalists to 11 Anti-Federalists, the latter of whom were from only four states: Massachusetts, New York, Virginia and South Carolina.[50] Among the Virginia delegation to the House was James Madison, Patrick Henry's chief opponent in the Virginia ratification battle. In retaliation for Madison's victory in that battle at Virginia's ratification convention, Henry and other Anti-Federalists, who controlled the Virginia House of Delegates, had gerrymandered a hostile district for Madison's planned congressional run and recruited Madison's future presidential successor, James Monroe, to oppose him.[51] Madison defeated Monroe after offering a campaign pledge that he would introduce constitutional amendments forming a bill of rights at the First Congress.[52]

This pledge was a significant change from Madison's rhetoric from just a few months earlier. In Federalist No. 49, he had raised concerns that proposing amendments might upset the country's delicate political situation and cause public chaos.[53] One year later, when speaking before the Virginia Ratifying Convention, Madison warned against the potential for chaos on the state level as well: "If amendments are to be proposed by one state, other states have the same right, and will also propose alterations. These cannot but be dissimilar, and opposite in their nature."[54] Like Hamilton, Madison believed that the enumerated powers in the Constitution were sufficient to protect the peoples' rights. His opinion changed after a prolonged correspondence with his close friend and political ally Thomas Jefferson, who was firmly convinced of the need for a bill of rights to protect essential liberties like the freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and the right to jury trials.[55] In addition to Jefferson's influence, political circumstances forced Madison to reconsider the necessity of a bill of rights. Several states had only ratified the Constitution on the condition that a bill of rights would be included and many were calling for a second constitutional convention if that promise was not fulfilled, a situation that Madison considered to be disastrous.[56]

To prevent that from happening, Madison resolved to sponsor a bill of rights and head off his opponents who threatened to undo the difficult compromises of 1787 and open the entire Constitution to reconsideration, thus risking the dissolution of the new federal government. Writing to Jefferson, he stated, "The friends of the Constitution, some from an approbation of particular amendments, others from a spirit of conciliation, are generally agreed that the System should be revised. But they wish the revisal to be carried no farther than to supply additional guards for liberty."[57] He also felt that amendments guaranteeing personal liberties would "give to the Government its due popularity and stability".[58] Finally, he hoped that the amendments "would acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion".[59] Historians continue to debate the degree to which Madison considered the amendments of the Bill of Rights necessary, and to what degree he considered them politically expedient; in the outline of his address, he wrote, "Bill of Rights—useful—not essential—".[60]

On the occasion of his April 30, 1789 inauguration as the nation's first president, George Washington addressed the subject of amending the Constitution. He urged the legislators,

whilst you carefully avoid every alteration which might endanger the benefits of an united and effective government, or which ought to await the future lessons of experience; a reverence for the characteristic rights of freemen, and a regard for public harmony, will sufficiently influence your deliberations on the question, how far the former can be impregnably fortified or the latter be safely and advantageously promoted.[61][62]

Madison's proposed amendments

editJames Madison introduced a series of Constitutional amendments in the House of Representatives for consideration. Among his proposals was one that would have added introductory language stressing natural rights to the preamble.[63] Another would apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government. Several sought to protect individual personal rights by limiting various Constitutional powers of Congress. Like Washington, Madison urged Congress to keep the revision to the Constitution "a moderate one", limited to protecting individual rights.[63] Madison was deeply read in the history of government and used a range of sources in composing the amendments. The English Magna Carta of 1215 inspired the right to petition and to trial by jury, for example, while the English Bill of Rights of 1689 provided an early precedent for the right to keep and bear arms (although this applied only to Protestants) and prohibited cruel and unusual punishment.[64]

The greatest influence on Madison's text, however, was existing state constitutions.[65][66] Many of his amendments, including his proposed new preamble, were based on the Virginia Declaration of Rights drafted by Anti-Federalist George Mason in 1776.[67] To reduce future opposition to ratification, Madison also looked for recommendations shared by many states.[66] He did provide one, however, that no state had requested: "No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases."[68] He did not include an amendment that every state had asked for, one that would have made tax assessments voluntary instead of contributions.[69]

Crafting amendments

editFederalist representatives were quick to attack Madison's proposal, fearing that any move to amend the new Constitution so soon after its implementation would create an appearance of instability in the government.[70] The House, unlike the Senate, was open to the public, and members such as Fisher Ames warned that a prolonged "dissection of the constitution" before the galleries could shake public confidence.[71] A procedural battle followed, and after initially forwarding the amendments to a select committee for revision, the House agreed to take Madison's proposal up as a full body beginning on July 21, 1789.[72][73] The eleven-member committee made some significant changes to Madison's nine proposed amendments, including eliminating most of his preamble and adding the phrase "freedom of speech, and of the press".[74] The House debated the amendments for eleven days. Roger Sherman of Connecticut persuaded the House to place the amendments at the Constitution's end so that the document would "remain inviolate", rather than adding them throughout, as Madison had proposed.[75][76] The amendments, revised and condensed from twenty to seventeen, were approved and forwarded to the Senate on August 24, 1789.[77] The Senate edited these amendments still further, making 26 changes of its own. Madison's proposal to apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government was eliminated, and the seventeen amendments were condensed to twelve, which were approved on September 9, 1789.[78] The Senate also eliminated the last of Madison's proposed changes to the preamble.[79]

On September 21, 1789, a House–Senate Conference Committee convened to resolve the numerous differences between the two Bill of Rights proposals. On September 24, 1789, the committee issued this report, which finalized 12 Constitutional Amendments for House and Senate to consider. This final version was approved by joint resolution of Congress on September 25, 1789, to be forwarded to the states on September 28.[80][81] By the time the debates and legislative maneuvering that went into crafting the Bill of Rights amendments was done, many personal opinions had shifted. A number of Federalists came out in support, thus silencing the Anti-Federalists' most effective critique. Many Anti-Federalists, in contrast, were now opposed, realizing that Congressional approval of these amendments would greatly lessen the chances of a second constitutional convention.[82] Anti-Federalists such as Richard Henry Lee also argued that the Bill left the most objectionable portions of the Constitution, such as the federal judiciary and direct taxation, intact.[83] Madison remained active in the progress of the amendments throughout the legislative process. Historian Gordon S. Wood writes that "there is no question that it was Madison's personal prestige and his dogged persistence that saw the amendments through the Congress. There might have been a federal Constitution without Madison but certainly no Bill of Rights."[84][85]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Vice President Clinton and Vice President Gerry both died in office. Neither was replaced for the remainder of their respective terms, as the Constitution did not have a provision for filling a vice presidential vacancy prior to the adoption of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967.

- ^ (O.S. March 5, 1750)

References

edit- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Feldman 2017, p. 70

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 96–97, 128–130

- ^ Wood 2011, p. 104

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 129–130

- ^ Rutland 1987, p. 14.

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 136–137

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 56–57, 74–75

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 98–99, 121–122

- ^ Ketcham 2003, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 137–138

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 78–79

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Feldman 2017, p. 87

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 138–139, 144

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 82–83

- ^ Jóhannesson, Sveinn (September 1, 2017). "'Securing the State': James Madison, Federal Emergency Powers, and the Rise of the Liberal State in Postrevolutionary America". Journal of American History. 104 (2): 363–385. doi:10.1093/jahist/jax173. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ^ Robinson, Raymond H. (1999). "The Marketing of an Icon". George Washington: American Symbol. Hudson Hills. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-55595-148-1.

Figure 56 John Henry Hintermeister (American 1869–1945) Signing of the Constitution, 1925...Alternatively labeled Title to Freedom and the Foundation of American Government...".

- ^ Feldman 2017, p. 107

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 150–151

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 140–141

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 115–117

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Rutland 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 107–108

- ^ Branson, Roy (1979). "James Madison and the Scottish Enlightenment". Journal of the History of Ideas. 40 (2): 235–250. doi:10.2307/2709150. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709150.

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander; Madison, James; Jay, John (December 29, 1998). "The Federalist Papers No. 10". Yale Law School. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Fleischacker, Samuel (2002). "Adam Smith's Reception among the American Founders, 1776–1790". The William and Mary Quarterly. 59 (4): 897–924. doi:10.2307/3491575. ISSN 0043-5597. JSTOR 3491575.

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 152–166, 171

- ^ a b Wood 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 148–149

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 164–166

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 177–178

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 179–180

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed. (1961). The Federalist Papers. Penguin Putnam, Inc. pp. ix, xiii.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 31–35.

- ^ "Federalist No. 10". Hanover College. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 208–209

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 195–196, 213

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 215–216

- ^ a b Labunski 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 191–192

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 179–180

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 231–233

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Feldman 2017, pp. 239–240

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 182–183

- ^ Maier, p. 433.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 76.

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 159, 174.

- ^ James Madison, Federalist No. 49 https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-41-50

- ^ James Madison, Speeches in the Virginia Convention | pages=132 https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/1937/1356.05_Bk.pdf

- ^ Thomas Jefferson, To James Madison from Thomas Jefferson, 20 December 1787 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0210

- ^ Broadwater, James Madison and the Constitution: Reassessing the "Madison Problem" | pages=220, 221 https://www.jstor.org/stable/26322533

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 162.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 77.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 192.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 188.

- ^ Gordon Lloyd. "Anticipating the Bill of Rights in the First Congress". TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Ashland, Ohio: The Ashbrook Center at Ashland University. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Labunski 2006, p. 198.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 80.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 199.

- ^ a b Madison introduced "amendments culled mainly from state constitutions and state ratifying convention proposals, especially Virginia's." Levy, p. 35

- ^ Virginia Declaration of Rights Archived January 2, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Library of Congress. Accessed July 12, 2013.

- ^ Ellis, p. 210.

- ^ Ellis, p. 212.

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 215.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 201.

- ^ Brookhiser, p. 81.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Ellis, p. 207.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 235.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 237.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 221.

- ^ Adamson, Barry (2008). Freedom of Religion, the First Amendment, and the Supreme Court: How the Court Flunked History. Pelican Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9781455604586. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Graham, John Remington (2009). Free, Sovereign, and Independent States: The Intended Meaning of the American Constitution. Foreword by Laura Tesh. Arcadia. Footnote 54, pp. 193–94. ISBN 9781455604579. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wood 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Levy, Leonard W. (1986). "Bill of Rights (United States)". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Wood 2009, p. 69.

- ^ Ellis, p. 206.

Bibliography

edit- Bordewich, Fergus M. (2016). The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-9193-1.

- Broadwater, Jeff. (2012). James Madison: A Son of Virginia and a Founder of a Nation. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3530-2.

- Brookhiser, Richard (2011). James Madison. Basic Books.

- Burstein, Andrew; Isenberg, Nancy (2010). Madison and Jefferson. Random House. ISBN 978-0-81297-9008.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2015). The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780385353410. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Feldman, Noah (2017). The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-9275-5.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515924-0.

- Green, Michael D. (1982). The Politics of Indian Removal (Paperback). University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7015-2.

- Hopkins, Callie (August 28, 2019). "The Enslaved Household of President James Madison". whitehousehistory.org. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America 1815–1848. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7.

- Kappler, Charles J. (1904). Indian Affairs. Laws and Treaties (PDF). Vol. II (Treaties). Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Ketcham, Ralph (1990). James Madison: A Biography (paperback ed.). Univ. of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1265-3.

- Ketcham, Ralph (2002). "James Madison". In Graff, Henry F. (ed.). The Presidents A Reference History (Third ed.). Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 57–70. ISBN 978-0-684-31226-2.

- Ketcham, Ralph (2003). James Madison: A Biography. American Political Biography Press.

- Keysaar, Alexander (2009). The Right to Vote. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02969-3.

- Labunski, Richard (2006). James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Landry, Alysa (January 26, 2016). "James Madison: Pushed Intermarriage Between Settlers and Indians". Ict News. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Langguth, A. J. (2006). Union 1812:The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2618-9.

- McCoy, Drew R. (1989). The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy. Cambridge University Press.

- Watts, Steven (1990). "The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy". The American Historical Review. 95 (4): 1288–1289. doi:10.2307/2163682. JSTOR 2163682. Review.

- McDonald, Forrest (1976). The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0330-5.

- Maier, Pauline (2010). Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. Simon & Schuster.

- "Montpelier The People, The Place, The Idea". montpelier.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Owens, Robert M. (2007). Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8.

- Rutland, Robert A. (1987). James Madison: The Founding Father. Macmillan Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-02-927601-3.

- Rutland, Robert A. (1990). The Presidency of James Madison. Univ. Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0465-4.

- Stewart, David (2007). The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. Simon and Schuster.[ISBN missing]

- Wills, Garry (2002). James Madison. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6905-1.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2011). The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States. The Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-290-2.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-83246-0.

External links

edit- James Madison: A Resource Guide at the Library of Congress

- Works by or about James Madison as Father of the Constitution at the Internet Archive

- Works by James Madison as Father of the Constitution at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)