Hair removal is the deliberate removal of body hair or head hair. This process is also known as epilation or depilation.

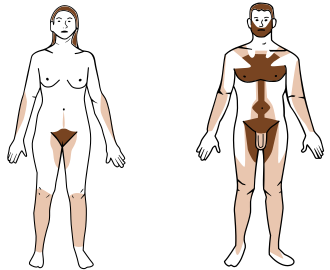

Hair is a common feature of the human body, exhibiting considerable variation in thickness and length across different populations. Hair becomes more visible during and after puberty. Additionally, men typically exhibit thicker and more conspicuous body hair than women.[1] Both males and females have visible body hair on the head, eyebrows, eyelashes, armpits, genital area, arms, and legs. Males and some females may also have thicker hair growth on their face, abdomen, back, buttocks, anus, areola, chest, nostrils, and ears. Hair does not generally grow on the lips, back of the ear, the underside of the hands or feet, or on certain areas of the genitalia.

Hair removal may be practiced for cultural, aesthetic, hygienic, sexual, medical, or religious reasons. Forms of hair removal have been practiced in almost all human cultures since at least the Neolithic era. The methods used to remove hair have varied in different times and regions.

The term "depilation" is derived from the Medieval Latin "depilatio," which in turn is derived from the Latin "depilare," a word formed from the prefix "de-" and the root "pilus," meaning "hair."

History

editFor centuries, hair removal has long shaped gender roles, served to signify social status and defined notions of femininity and the ideal "body image".[2][3] In early periods, the condition of being hairless was mostly done as a way to keep the body clean, using flint, seashells, beeswax and various other depilatory utensils and exfoliator substances, some highly questionable and highly caustic.[3][4] Ancient Rome also associated hair removal with status: a person with smooth skin was associated with purity and superiority. Removing body hair was done by both men and women[2][3][5][6] Psilothrum or psilotrum (Ancient Greek: ψίλωθρον) and dropax (Ancient Greek: δρῶπαξ) were depilatories in ancient Greece and Rome.[7][8][9]

In Ancient Egypt, besides being a fashion statement for affluent Egyptians of all genders,[3][10] hair removal served as a treatment for louse infestation, which was a prevalent issue in the region.[11] Very often, they would replace the removed head hair with a Nubian wig, which was seen as easier to maintain and also fashionable.[11] Ancient Egyptian priests also shaved or depilated all over daily, so as to present a "pure" body before the images of the gods.[citation needed]

In ancient times, one highly abrasive depilatory paste consisted of an admixture of slaked lime, water, wood-ash and yellow orpiment (arsenic trisulfide); In rural India and Iran, where this mixture is called vajibt, it is still commonly used to remove pubic hair.[3][4][12] In other cultures, oil extracted from unripe olives (which had not reached one-third of their natural stage of ripeness) was used to remove body hair.[13]

During the medieval period, Catholic women were expected to let their hair grow long as a display of femininity, whilst keeping the hair concealed by wearing a wimple headdress in public places.[2] The face was the only area where hair growth was considered unsightly; 14th-century ladies would also pick off hair from their foreheads to recede the hairline and give their face a more oval form. From the mid-16th century, it is said when Queen Elizabeth I came to power, she made eyebrow removal fashionable.[2]

By the 18th century, body hair removal was still considered a non-necessity by European and American women. But in 1760, when the first safety straight razor appeared for men to safely shave their beard and not inadvertently cut themselves, some women allegedly used this safety razor too.[2] It was invented in Paris by the French master cutler Jean-Jacques Perret, author of La pogonotomie, ou L'art d'apprendre à se raser soi-même (Pogonotomy, or The Art of Learning to Shave).[2]

It was not until the late 19th century that women in Europe and America started to make hair removal a component of their personal care regime. According to Rebecca Herzig, the modern-day notion of body hair being unwomanly can be traced back to Charles Darwin's book first published in 1871 "The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex". Darwin's theory of natural selection associated body hair with "primitive ancestry and an atavistic return to earlier less developed forms", writes Herzig, a professor of gender and sexuality studies at Bates College in Maine.[2] Darwin also suggests having less body hair was an indication of being more evolved and sexually attractive.[2] As Darwin's ideas polarized, other 19th century medical and scientific experts started to link hairiness to "sexual inversion, disease pathology, lunacy, and criminal violence". Those connotations were mostly applied to women's and not men's body hair.[2]

By the early 20th century, the upper- and middle-class white America increasingly saw smooth skin as a marker of femininity, and female body hair as repulsive, with hair removal giving "a way to separate oneself from cruder people, lower class and immigrant".[2]

Harper's Bazaar, in 1915, was the first women's fashion magazine to run a campaign devoted to the removal of underarm hair as "a necessity". Shortly after, Gillette launched the first safety razor marketed specifically for women—the "Milady Décolleté Gillette", one that solves "...an embarrassing personal problem" and keeps the underarm "...white and smooth".[2]

Cultural and sexual aspects

editBody hair characteristics such as thickness and length vary across human populations, some people have less pronounced body hair and others have more conspicuous body hair characteristics.

Each culture of human society developed social norms relating to the presence or absence of body hair, which has changed from one time to another. Different standards of human physical appearance and physical attractiveness can apply to females and males. People whose hair falls outside a culture's aesthetic body image standards may experience real or perceived social acceptance problems, psychological distress and social pressure. For example, for women in several societies, exposure in public of body hair other than head hair, eyelashes and eyebrows is generally considered to be unaesthetic, unattractive and embarrassing.[14]

With the increased popularity in many countries of women wearing fashion clothing, sportswear and swimsuits during the 20th century and the consequential exposure of parts of the body on which hair is commonly found, there has emerged a popularization for women to remove visible body hair, such as on legs, underarms and elsewhere, or the consequences of hirsutism and hypertrichosis.[2][15] In most of the Western world, for example, the vast majority of women regularly shave their legs and armpits, while roughly half also shave hair that may become exposed around their bikini pelvic area (often termed the "bikini line").[2]

In Western and Asian cultures, in contrast to most Middle Eastern cultures, a majority of men are accustomed to shaving their facial hair, so only a minority of men reveal a beard, even though fast-growing facial hair must be shaved daily to achieve a clean-shaven or beardless appearance. Some men shave because they cannot genetically grow a "full" beard (generally defined as an even density from cheeks to neck), their beard color is genetically different from their scalp hair color, or because their facial hair grows in many directions, making a groomed or contoured appearance difficult to achieve. Some men shave because their beard growth is excessive, unpleasant, or coarse, causing skin irritation. Some men grow a beard or moustache from time to time to change their appearance or visual style.

Some men tonsure or head shave, either as a religious practice, a fashion statement, or because they find a shaved head preferable to the appearance of male pattern baldness, or in order to attain enhanced cooling of the skull – particularly for people suffering from hyperhidrosis. A much smaller number of Western women also shave their heads, often as a fashion or political statement.

Some women also shave their heads for cultural or social reasons. In India, tradition required widows in some sections of the society to shave their heads as part of being ostracized (see Women in Hinduism § Widowhood and remarriage). The outlawed custom is still infrequently encountered mostly in rural areas. Society at large and the government are working to end the practice of ostracizing widows.[16] In addition, it continues to be common practice for men to shave their heads prior to embarking on a pilgrimage.

The unibrow is considered a sign of beauty and attractiveness for women in Oman and for both genders in Tajikistan, often emphasized with kohl.[2] In Middle Eastern societies, regular trimming or removal of female and male underarm hair and pubic hair has been considered proper personal hygiene, necessitated by local customs, for many centuries.[3][17][18] Young girls and unmarried women, however, are expected to retain their body hair until shortly before marriage, when the whole body is depilated from the neck down.[3]

In China, body hair has long been regarded as normal, and even today women are confronted with far less social pressure to remove body hair.[2] The same attitude exists in other countries in Asia. While hair removal has become routine for many of the continent's younger women, trimming or removing pubic hair, for instance, is not as common or popular as in the Western world,[2] where both women and men may trim or remove all their pubic hair for aesthetic or sexual reasons. This custom can be motivated by reasons of potentially increased personal cleanliness or hygiene, heightened sensitivity during sexual activity, or the desire to take on a more exposed appearance or visual appeal, or to boost self-esteem when affected by excessive hair. In Korea, pubic hair has long been considered a sign of fertility and sexual health, and it has been reported in the mid-2010s that some Korean women were undergoing pubic hair transplants, to add extra hair,[2] especially when affected by the condition of pubic atrichosis (or hypotrichosis), which is thought to affect a small percentage of Korean women.[19]

Unwanted or excessive hair is often removed in preparatory situations by both sexes, in order to avoid any perceived social stigma or prejudice. For example, unwanted or excessive hair may be removed in preparation for an intimate encounter, or before visiting a public beach or swimming pool.

Though traditionally in Western culture women remove body hair and men do not, some women choose not to remove hair from their bodies, either as a non-necessity or as an act of rejection against social stigma, while some men remove or trim their body hair, a practice that is referred to in modern society as being a part of "manscaping" (a portmanteau expression for male-specific grooming).

Fashions

editThe term "glabrousness" also has been applied to human fashions, wherein some participate in culturally motivated hair removal by depilation (surface removal by shaving, dissolving), or epilation (removal of the entire hair, such as waxing or plucking).

Although the appearance of secondary hair on parts of the human body commonly occurs during puberty, and therefore, is often seen as a symbol of adulthood, removal of this and other hair may become fashionable in some cultures and subcultures. In many modern Western cultures, men are encouraged to shave their beards, and women are encouraged to remove hair growth in various areas. Commonly depilated areas for women are the underarms, legs, and pubic hair. Some individuals depilate the forearms. In recent years, bodily depilation in men has increased in popularity among some subcultures of Western males.[citation needed]

For men, the practice of depilating the pubic area is common, especially for aesthetic reasons. Most men will use a razor to shave this area, however, as best practice, it is recommended to use a body trimmer to shorten the length of the hair before shaving it off completely.

Cultural and other influences

editIn ancient Egypt, depilation was commonly practiced, with pumice and razors used to shave.[20][21] In both Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, the removal of body and pubic hair may have been practiced among both men and women. It is represented in some artistic depictions of male and female nudity, [citation needed] examples of which may be seen in red figure pottery and sculptures like the Kouros of Ancient Greece in which both men and women were depicted without body or pubic hair. Emperor Augustus was said, by Suetonius, to have applied "hot nutshells" on his legs as a form of depilation.[22]

In the clothes free movement, the term "smoothie" refers to an individual who has removed their body hair. In the past, such practices were frowned upon and in some cases, forbidden: violators could face exclusion from the club. Enthusiasts grouped together and formed societies of their own that catered to that fashion, and smoothies became a major percentage at some nudist venues.[23] The first Smoothie club (TSC) was founded by a British couple in 1991.[24] A Dutch branch was founded in 1993[25] in order to give the idea of a hairless body greater publicity in the Netherlands. Being a Smoothie is described by its supporters as exceptionally comfortable and liberating. The Smoothy-Club is also a branch of the World of the Nudest Nudist (WNN) and organizes nudist ship cruises and regular nudist events.

Other reasons

editReligion

editHead-shaving (tonsure) is a part of some Buddhist, Christian, Muslim, Jain and Hindu traditions.[26] Buddhist and Christian monks generally undergo some form of tonsure during their induction into monastic life.[citation needed]

Within Amish society, tradition ordains men to stop shaving a part of their facial hair upon marriage and grow a Shenandoah style beard which serves the significance of wearing a wedding ring, moustaches are rejected as they are regarded as martial (traditionally associated with the military).[27]

In Judaism (see Shaving in Judaism), there is no obligation for women to remove body hair or facial hair, unless they wish to do so. However, in preparation for a woman's immersion in a ritual bath after concluding her days of purification (following her menstrual cycle), the custom of Jewish women is to shave off their pubic hair.[28] During a mourning ritual, Jewish men are restricted in the Torah and Halakha to using scissors and prohibited from using a razor blade to shave their beards or sideburns,[29] and, by custom, neither men nor women may cut or shave their hair during the shiva period.[30][31]

The Baháʼí Faith recommends against complete and long-term head-shaving outside of medical purposes. It is not currently practiced as a law, contingent upon a future decision by the Universal House of Justice, its highest governing body. Sikhs take an even stronger stance, opposing all forms of hair removal. One of the "Five Ks" of Sikhism is Kesh, meaning "hair".[32] Baptized Sikhs are specifically instructed to have unshorn Kesh (the hair on their head and beards for men) as a major tenet of the Sikh faith. To Sikhs, the maintenance and management of long hair is a manifestation of one's piety.[32]

The majority of Muslims believe that adult removal of pubic and axillary hair, as a hygienic measure, is religiously beneficial. Under Muslim law (Sharia), it is recommended to keep the beard.[citation needed] A Muslim may trim or cut hair on the head. In the 9th century, the use of chemical depilatories for women was introduced by Ziryab in Al-Andalus.[citation needed]

Medical

editThe body hair of surgical patients is often removed beforehand on the skin surrounding surgical sites. Shaving was the primary form of hair removal until reports in 1983 showed that it may lead to an increased risk of infection. [33] Clippers are now the recommended pre-surgical hair removal method.[34][35] A 2021 systematic review brought together evidence on different techniques for hair removal before surgery. This involved 25 studies with a total of 8919 participants. Using a razor probably increases the chance of developing a surgical site infection compared to using clippers or hair removal cream or not removing hair before surgery.[36] Removing hair on the day of surgery rather than the day before may also slightly reduce the number of infections.[36]

Some people with trichiasis find it medically necessary to remove ingrown eyelashes.[37]

The shaving of hair has sometimes been used in attempts to eradicate lice or to minimize body odor due to the accumulation of odor-causing micro-organisms in hair. In extreme situations, people may need to remove all body hair to prevent or combat infestation by lice, fleas and other parasites. Such a practice was used, for example, in Ancient Egypt.[38]

It has been suggested that an increasing percentage of humans removing their pubic hair has led to reduced crab louse populations in some parts of the world.[39][40]

In the military

editA buzz cut or completely shaven haircut is common in military organizations where, among other reasons, it is considered to promote uniformity and neatness.[41][42] Most militaries have occupational safety and health policies that govern the hair length and hairstyles permitted;[41] in the field and living in close-quarter environments where bathing and sanitation can be difficult, soldiers can be susceptible to parasite infestation such as head lice, that are more easily propagated with long and unkempt hair.[43] It also requires less maintenance in the field and in adverse weather it dries more quickly. Short hair is also less likely to cause severe burns from flash flame exposure (as a result of flash fires from explosions) which can easily set hair alight.[41] Short hair can also minimize interference with safety equipment and fittings attached to the head, such as combat helmets and NBC suits.[41] Militaries may also require men to maintain clean-shaven faces as facial hair can prevent an air-tight seal between the face and military gas masks or other respiratory equipment, such as a pilot's oxygen mask, or full-face diving mask.[41] The process of testing whether a mask adequately fits the face is known as a "respirator fit test".

In many militaries, head-shaving (known as the induction cut) is mandatory for men when beginning their recruit training. However, even after the initial recruitment phase, when head-shaving is no longer required, many soldiers maintain a completely or partially shaven hairstyle (such as a "high and tight", "flattop" or "buzz cut") for personal convenience or neatness. Head-shaving is not required and is often not permitted for women in military service, although they must have their hair cut or tied to regulation length.[42] For example, the shortest hair a female soldier can have in the U.S. Army is 1/4 inch from the scalp.[44]

In sport

editIt is a common practice for professional footballers (soccer players) and road cyclists to remove leg hair for a number of reasons. In the case of a crash or tackle, the absence of the leg hair means the injuries (usually road rash or scarring) can be cleaned up more efficiently, and treatment is not impeded. Professional cyclists, as well as professional footballers, also receive regular leg massages, and the absence of hair reduces the friction and increases their comfort and effectiveness.[citation needed] Football players are also required to wear shin guards, and in case of a skin rash, the affected area can be treated more efficiently.

It is also common for competitive swimmers to shave the hair off their legs, arms, and torsos (and even their whole bodies from the neckline down), to reduce drag and provide a heightened "feel" for the water by removing the exterior layer of skin along with the body hair.[45]

As punishment

editIn some situations, people's hair is shaved as a punishment or a form of humiliation. After World War II, head-shaving was a common punishment in France, the Netherlands, and Norway for women who had collaborated with the Nazis during the occupation, and, in particular, for women who had sexual relations with an occupying soldier.[46]

In the United States, during the Vietnam War, conservative students would sometimes attack student radicals or "hippies" by shaving beards or cutting long hair. One notorious incident occurred at Stanford University, when unruly fraternity members grabbed Resistance founder (and student-body president) David Harris, cut off his long hair, and shaved his beard.

During European witch-hunts of the Medieval and Early Modern periods, alleged witches were stripped naked and their entire body shaved to discover the so-called witches' marks. The discovery of witches' marks was then used as evidence in trials.[47]

Inmates have their heads shaved upon entry at certain prisons.[citation needed]

Forms of hair removal and methods

edit- Depilation is the removal of the part of the hair above the surface of the skin. The most common form of depilation is shaving or trimming. Another option is the use of chemical depilatories, which work by breaking the disulfide bonds that link the protein chains that give hair its strength.

- Epilation is the removal of the entire hair, including the part below the skin. Methods include waxing, sugaring, epilators, lasers, threading, intense pulsed light or electrology. Hair is also sometimes removed by plucking with tweezers.

Depilation methods

edit"Depilation", or temporary removal of hair to the level of the skin, lasts several hours to several days and can be achieved by

- Shaving or trimming (manually or with electric shavers which can be used on pubic hair or body hair)

- Depilatories (creams or "shaving powders" which chemically dissolve hair)

- Friction (rough surfaces used to buff away hair)

Epilation methods

edit"Epilation", or removal of the entire hair from the root, lasts several days to several weeks and may be achieved by

- Tweezing (hairs are tweezed, or pulled out, with tweezers or with fingers)

- Waxing (a hot or cold layer is applied and then removed with porous strips)

- Sugaring (hair is removed by applying a sticky paste to the skin in the direction of hair growth and then peeling off with a porous strip)

Threading in Wenchang, Hainan, China - Threading (also called fatlah or khite in Arabic, or band in Persian) in which a twisted thread catches hairs as it is rolled across the skin

- Epilators (mechanical devices that rapidly grasp hairs and pull them out).

- Drugs that directly attack hair growth or inhibit the development of new hair cells. Hair growth will become less and less until it finally stops; normal depilation/epilation will be performed until that time. Hair growth will return to normal if use of product is discontinued.[48] Products include the following:

- The pharmaceutical drug eflornithine hydrochloride (with the trade names Vaniqa and Follinil) inhibits the enzyme ornithine decarboxylase, preventing new hair cells from producing putrescine for stabilizing their DNA.

- Antiandrogens, including spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, flutamide, bicalutamide, and finasteride, can be used to reduce or eliminate unwanted body hair, such as in the treatment of hirsutism.[49][50][51][52] Although effective for reducing body hair, antiandrogens have little effect on facial hair.[53] However, slight effectiveness may be observed, such as some reduction in density/coverage and slower growth.[citation needed] Antiandrogens will also prevent further development of facial hair, despite only minimally affecting that which is already there. With the exception of 5α-reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride,[49][54] antiandrogens are contraindicated in men due to the risk of feminizing side effects such as gynecomastia as well as other adverse reactions (e.g., infertility), and are generally only used in women for cosmetic/hair-reduction purposes.[55]

Permanent hair removal

editElectrology has been practiced in the United States since 1875.[56] It is approved by the FDA. This technique permanently destroys germ cells[citation needed] responsible for hair growth by way of the insertion of a fine probe into the hair follicle and the application of a current adjusted to each hair type and treatment area.[citation needed] Electrology is the only permanent hair removal method recognized by the FDA.[57]

Permanent hair reduction

edit- Laser hair removal (lasers and laser diodes): Laser hair removal technology became widespread in the US and many other countries from the 1990s onwards. It has been approved in the United States by the FDA since 1997. With this technology, light is directed at the hair and is absorbed by dark pigment, resulting in the destruction of the hair follicle. This hair removal method sometimes becomes permanent after several sessions. The number of sessions needed depends upon the amount and type of hair being removed.

- Intense pulsed light (IPL) This technology is becoming more common for at-home devices, many of which are advertised as "laser hair removal" but actually use IPL technology.

- Diode epilation (high energy LEDs but not laser diodes)

Clinical comparisons of effectiveness

editA 2006 review article in the journal "Lasers in Medical Science" compared intense pulsed light (IPL) and both alexandrite and diode lasers. The review found no statistical difference in effectiveness, but a higher incidence of side effects with diode laser-based treatment. Hair reduction after 6 months was reported as 68.75% for alexandrite lasers, 71.71% for diode lasers, and 66.96% for IPL. Side effects were reported as 9.5% for alexandrite lasers, 28.9% for diode lasers, and 15.3% for IPL. All side effects were found to be temporary and even pigmentation changes returned to normal within 6 months.[58]

A 2006 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that alexandrite and diode lasers caused 50% hair reduction for up to 6 months, while there was no evidence of hair reduction from intense pulsed light, neodymium-YAG or ruby lasers.[59]

Experimental or banned methods

edit- Photodynamic therapy for hair removal (experimental)

- X-ray hair removal is an efficient, and usually permanent, hair removal method, but also causes severe health problems, occasional disfigurement, and even death.[60] It is illegal in the United States.

Doubtful methods

editMany methods have been proposed or sold over the years without published clinical proof they can work as claimed.

- Electric tweezers

- Transdermal electrolysis

- Transcutaneous hair removal

- Microwave hair removal

- Foods and dietary supplements

- Non-prescription topical preparations (also called "hair inhibitors", "hair retardants", or "hair growth inhibitors")

Advantages and disadvantages

editThere are several disadvantages to many of these hair removal methods.

Hair removal can cause issues: skin inflammation, minor burns, lesions, scarring, ingrown hairs, bumps, and infected hair follicles (folliculitis).

Some removal methods are not permanent, can cause medical problems and permanent damage, or have very high costs. Some of these methods are still in the testing phase and have not been clinically proven.

One issue that can be considered an advantage or a disadvantage depending upon an individual's viewpoint, is that removing hair has the effect of removing information about the individual's hair growth patterns due to genetic predisposition, illness, androgen levels (such as from pubertal hormonal imbalances or drug side effects), and/or gender status.

In the hair follicle, stem cells reside in a discrete microenvironment called the bulge, located at the base of the part of the follicle that is established during morphogenesis but does not degenerate during the hair cycle. The bulge contains multipotent stem cells that can be recruited during wound healing to help repair the epidermis.[61]

See also

editReferences

edit- Citations

- ^ Shellow V (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 67. ISBN 0-313-33145-6.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Cerini M (2020-03-03). "Beauty: Why women feel pressured to shave". Atlanta: CNN Style. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lowe S (2016). hair. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781628922868. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ a b Bickart N (2019). "He Found a Hair and It Bothered Him: Female Pubic Hair Removal in the Talmud". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (35): 128–152. doi:10.2979/nashim.35.1.05. JSTOR 10.2979/nashim.35.1.05. S2CID 214436061. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ Stewart, Susan (2019), ""Gleaming and Deadly White"", Toxicology in Antiquity, Elsevier, pp. 301–311, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815339-0.00020-2, ISBN 978-0-12-815339-0, retrieved 2024-04-06

- ^ Ivleva, Tatiana; Collins, Rob, eds. (2022). Un-Roman sex: gender, sexuality, and lovemaking in the Roman provinces and frontiers. Routledge monographs in classical studies (First issued in paperback ed.). London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-032-33632-9.

- ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Psilothrum

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Psilothrum

- ^ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Psilothrum

- ^ "Hair removal - Y Ganolfan Eifftaidd / Egypt Centre".

- ^ a b "The nit-picking pharaohs". New Scientist. No. 1718. London. 1990-05-26. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ Alpha Beta la-Ben Sira, s.v. נסכסיר (As2S3), in Greek = ἀρσενικόν; in Syriac = ܙܪܢܟ (zernikh). Mixed with two parts of slaked lime, orpiment is still commonly used in rural India as a depilatory.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Menahot 86a, s.v. אנפקינון

- ^ Tschachler H, Devine M, Draxlbauer M (2003). The EmBodyment of American Culture. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 61–62. ISBN 3-8258-6762-5.

- ^ "Who decided women should shave their legs and underarms?". The Straight Dope. 1991-02-06. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ^ Shunned from society, widows flock to city to die, 2007-07-05, CNN.com, Retrieved 2007-07-05

- ^ Kutty A (13 September 2005). "Islamic Ruling on Waxing Unwanted Hair". Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 29 March 2006.

- ^ Schick IC (2009). "Some islamic determinants of dress and personal appearance in southwest Asia". Khila'-Journal for Dress and Textiles of the Islamic World. 3: 25. doi:10.2143/KH.3.0.2066221.

- ^ Lee YR, Lee SJ, Kim JC, Ogawa H (November 2006). "Hair restoration surgery in patients with pubic atrichosis or hypotrichosis: review of technique and clinical consideration of 507 cases". Dermatologic Surgery. 32 (11): 1327–1335. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32302.x. PMID 17083584. S2CID 12823424.

- ^ Boroughs M, Cafri G, Thompson JK (2005). "Male Body Depilation: Prevalence and Associated Features of Body Hair Removal". Sex Roles. 52 (9–10): 637–644. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-3731-9. S2CID 143990623.

- ^ Manniche L (1999). Sacred luxuries : fragrance, aromatherapy, and cosmetics in Ancient Egypt. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780801437205.

- ^ The Twelve Caesars, Aug. 68.

- ^ "smooth naturists & nudists - Smoothies". Euro Naturist. Archived from the original on 2005-05-08.

- ^ "World of the Nudest Nudist, beauty of the shaved body". Archived from the original on August 14, 2007.

- ^ "World of the Nudest Nudist - home of the barest naturists". Wnn.nu. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ Karthikeyan K (January 2009). "Tonsuring: Myths and facts". International Journal of Trichology. 1 (1). MedKnow Publications: 33–34. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.51927. PMC 2929550. PMID 20805974.

- ^ "The Amish". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Teherani D (2019). Sefer Ma'ayan Ṭaharah Hashalem (The Complete Book 'Wellspring of Purification') (in Hebrew) (2 ed.). Betar Ilit: Beit ha-hora'ah de-kahal kadosh sepharadim. p. 145 (chapter 16, section 41). OCLC 232673878.

- ^ Farber Z (2014). "The Prohibition of Shaving in the Torah and Halacha". TheTorah.com. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ "Jewish Practices & Rituals: Beards". Jewish Virtual Library. December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Death & Bereavement in Judaism: Death and Mourning". Jewish Virtual Library. December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Trüeb RM (January–March 2017). "From Hair in India to Hair India". International Journal of Trichology. 9 (1). MedKnow Publications: 1–6. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_10_17. PMC 5514789. PMID 28761257.

- ^ "The Lancet, 11 June 1983, Volume 321, Issue 8337 - Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 8337, Pages 1291-1344". www.thelancet.com. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ^ "SSI PREVENTION – PATIENT PREPARATION: BATHING AND HAIR REMOVAL" (PDF). World Health Organisation.

- ^ Ortolon K (April 2006). "Clip, Don't Nick: Physicians Target Hair Removal to Cut Surgical Infections". Texas Medicine. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ a b Tanner J, Melen K, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (August 2021). "Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (8): CD004122. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004122.pub5. PMC 8406791. PMID 34437723.

- ^ Bailey R (June 6, 2011). "Does going 'against the grain' give you a better shave?". Men's Health. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Kenawy M, Abdel-Hamid Y (January 2015). "Insects in Ancient (Pharaonic) Egypt: A Review of Fauna, Their Mythological and Religious Significance and Associated Diseases". Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences. A, Entomology. 8 (1). Egyptian Society of Biological Sciences: 15–32. doi:10.21608/eajbsa.2015.12919. ISSN 1687-8809 – via Academic Search Complete.

- ^ Armstrong NR, Wilson JD (June 2006). "Did the "Brazilian" kill the pubic louse?". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (3): 265–266. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.018671. PMC 2564756. PMID 16731684.

- ^ Bloomberg: Brazilian bikini waxes make crab lice endangered species, published 13 January 2013, retrieved 14 January 2013

- ^ a b c d e Basic military requirements. Pensacola, Florida: Naval Education and Training Professional Development and Technology Center. 1999. pp. 10–29, 10–30, 10–31, 12–15, 12–27.

- ^ a b Goldmith C (2019). "Boot Camp". Women in the Military. Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group. ISBN 9781541557086.

- ^ United States. Surgeon-General's Office (1945). "Control of Lice". War Department Field Manual: Military Sanitation. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 129–132.

- ^ Ferdinando L (2014). "Army releases latest policies on female hairstyles, tattoos". United States Army. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Kostich A (2001-05-15). "Why Swimmers Shave Their Bodies". active.com. Active network. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Vinen R (1 December 2007). The Unfree French: Life Under the Occupation. Yale University Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-300-12601-3.

- ^ Brooks RB (2020-05-21). "What is a Witches' Mark?". Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- ^ "Eflornithine Monohydrate Chloride (Eflornithine 11.5% cream)". nhs.uk. NHS. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ a b Becker KL (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1004–1005. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- ^ Niewoehner CB (2004). Endocrine Pathophysiology. Hayes Barton Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-1-59377-174-4.

- ^ Falcone T, Hurd WW (22 May 2013). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-1-4614-6837-0.

- ^ Erem C (2013). "Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment". Acta Clinica Belgica. 68 (4): 268–274. doi:10.2143/ACB.3267. PMID 24455796. S2CID 39120534.

- ^ Heath RA (1 January 2006). The Praeger Handbook of Transsexuality: Changing Gender to Match Mindset. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-0-275-99176-0.

- ^ Blume-Peytavi U, Whiting DA, Trüeb RM (26 June 2008). Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7.

- ^ Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster G (21 March 2011). Acne Vulgaris. CRC Press. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-1-61631-009-7.

- ^ Michel CE. Trichiasis and distichiasis; with an improved method for radical treatment. St. Louis Clinical Record, 1875 Oct; 2:145-148

- ^ "Removing hair safely". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Toosi P, Sadighha A, Sharifian A, Razavi GM (April 2006). "A comparison study of the efficacy and side effects of different light sources in hair removal". Lasers in Medical Science. 21 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s10103-006-0373-2. PMID 16583183. S2CID 10093379.

- ^ Haedersdal M, Gøtzsche PC (October 2006). "Laser and photoepilation for unwanted hair growth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD004684. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004684.pub2. PMID 17054211.

- ^ Bickmore H (2004). Milady's Hair Removal Techniques: A Comprehensive Manual. Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 978-1401815554. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ Blanpain C, Fuchs E (2006). "Epidermal stem cells of the skin". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 22: 339–373. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. PMC 2405915. PMID 16824012.

Further reading

edit- Aldraibi MS, Touma DJ, Khachemoune A (January 2007). "Hair removal with the 3-msec alexandrite laser in patients with skin types IV-VI: efficacy, safety, and the role of topical corticosteroids in preventing side effects". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 6 (1): 60–66. PMID 17373163.

- Alexiades-Armenakas M (2006). "Laser hair removal". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 5 (7): 678–679. PMID 16865877.

- Eremia S, Li CY, Umar SH, Newman N (November 2001). "Laser hair removal: long-term results with a 755 nm alexandrite laser". Dermatologic Surgery. 27 (11): 920–924. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.01074.x. PMID 11737124. S2CID 25731335.

- Herzig RM (2015). Plucked: A History of Hair Removal. New York: New York University Press.

- McDaniel DH, Lord J, Ash K, Newman J, Zukowski M (June 1999). "Laser hair removal: a review and report on the use of the long-pulsed alexandrite laser for hair reduction of the upper lip, leg, back, and bikini region". Dermatologic Surgery. 25 (6): 425–430. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08118.x. PMID 10469087.

- Wanner M (2005). "Laser hair removal". Dermatologic Therapy. 18 (3): 209–216. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05020.x. PMID 16229722. S2CID 43469940.

- Warner J, Weiner M, Gutowski KA (June 2006). "Laser hair removal". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 49 (2): 389–400. doi:10.1097/00003081-200606000-00020. PMID 16721117.