Whitewashing in art is the practice of altering the racial identity of historical and mythological figures in art as a part of a larger pattern of erasing and distorting the histories and contributions of non-whites. It mirrors the racial biases and prejudices of those times, which continue to impact society today. It encompasses various facets reflecting historical biases.[1]

Overview edit

In Western art, the omission of black-skinned figures from mythology and history has been a subject of debate, exemplified by the portrayal of Andromeda as white in Clash of the Titans films, despite her original depiction as a black princess from Ethiopia.[1] This phenomenon extends beyond art, where the term "whitewashing" refers to the masking or downplaying of diverse realities, often leading to a predominant white perspective. It can distort representation, potentially overlooking contributions from people of colour and promoting a more monochromatic narrative.[2]

Snow-blindness edit

Despite the significant presence of Black people in Europe dating back to at least the 16th century, their representation in art history is often skewed or absent. When present, Black bodies are usually portrayed in subservient roles, with their humanity and individuality often entirely denied.[3]

For example, the Royal Albert Memorial Museum's (RAMM) portrait of an African was incorrectly attributed to Ignatius Sancho. This is dubbed snow-blindness and it is common practice when naming European subjects in portraits from the 17th century onwards, as while the African figures depicted alongside them are often referred to as "A Negro' or 'and Servant".[4] Also, in most historical European paintings, a Black figure is used as a prop or an object, existing solely to frame and reflect the white presence. Even when Black figures are depicted in fine clothing, it's often a deceptive representation, with the fancy silks and lace merely serving as decoration that masks the brutal reality of an enslaved life.[3]

British actor and author Paterson Joseph calls this practice racist and dehumanising, and urged the international art community to make efforts to identify and name these figures.[4]

Many institutions are now addressing this issue by re-evaluating how they acquire, curate, and display works. The history of Black people in Europe is often viewed through the lens of slavery and colonialism.[3]

In 2017, the "The Black Figure in the European Imaginary" exhibition that took place at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. This exhibition brought together 31 artworks from the 18th and 19th centuries, all created by European artists but sourced from American collections. The article emphasizes that the understanding of Black individuals during this period was often influenced by their roles as slaves, servants, or exotic foreigners, and was shaped by preconceived notions. These perceptions were largely influenced by colonialism, imperialism, slavery, abolition, and racism. The exhibition categorized the artworks into four groups: slaves and servants, artists' models, historical and literary figures, and exotic themes. The article highlights a painting titled "Portrait of a Youth in an Embroidered Vest" by French painter Marie-Victoire Lemoine as an example of how Black servants were often depicted as luxury accessories for the elite.[5]

According to art historian and curator Adrienne L. Childs,[6] interestingly, the exhibition indicates that European artists were more likely to depict Black figures with individuality and dignity, a contrast to the racist exaggerations prevalent in America during the same period. However, these depictions were also complex and nuanced due to underlying themes of objectification, servitude, and hierarchical attitudes about race.[5]

"Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe" exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum discusses an exhibition that highlighted the African presence in European art during the Renaissance. The exhibition, which was the first of its kind, showcased over sixty European artworks from around 1480 to 1605, including both known and anonymous African figures. The artworks were divided into two parts: the European context and the individuals themselves. The European context section explored the perceptions and assumptions about Africa held by Europeans of the time. The individuals section featured portraits of Africans, some of whom were likely real people painted from life.[7][8][9]

According to the Curator of Renaissance and Baroque Art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore Joaneath Spicer,[10] often a dark antipode to white and lightness, black carried a negative stigma, though black skin was attributed to burning from sun exposure in the torrid zone1. But later associations with the sin of Ham, son of Noah, led to the ideology of skin pigment as a cursed marker of moral inferiority that so frequently recurred in later racialist theory.[8]

Notable examples edit

Jesus edit

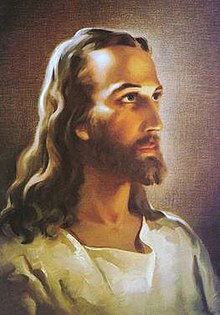

The portrayal of Jesus Christ as a white man with European features is a common occurrence in art history, despite the fact that he was a Hebrew man from the Middle East. This trend became particularly noticeable during the Renaissance, with famous artworks like Leonardo da Vinci's "Last Supper" and Michelangelo's "Last Judgment" in the Sistine Chapel depicting him as white. The most widely reproduced image of Jesus is Warner Sallman's "Head of Christ" from 1940, which presents him with light eyes and hair.[11]

Queen of Sheba edit

Queen of Sheba, a significant character in biblical and Quranic stories, has often been depicted as a white woman in art, especially during the Renaissance. This is a departure from her historical portrayal as a woman of colour. This change became prominent in the Renaissance, with her image being not only whitewashed but also sexualised. This can be seen in artworks like Edward Poynter's 1890 painting, "The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon".[1]

Andromeda edit

Andromeda, a princess from Ethiopia in Greek mythology, has been subjected to whitewashing in art, particularly during the Renaissance period.[1][12] Historically, Andromeda was depicted as a black princess. However, in many Renaissance artworks, she is portrayed as white. For instance, in Piero di Cosimo's painting "Perseus Freeing Andromeda" from the 1510s, Andromeda is depicted as whiter than all the figures around her, including a black musician and her parents, who are considerably darker.[1]

Ancient sculptures edit

Contrary to popular belief, ancient sculptures were not bare marble but were painted in bright shades of blue, red, yellow, brown, and other hues. Romans made copies of Greek bronze originals in different coloured marbles to add skin tone. However, this fact has been overlooked, and the narrative of white marble as the epitome of beauty continues to be told.[13][14]

Over the past few decades, scientists have been studying the traces of paint, inlay, and gold leaf used on these statues and using digital technologies to restore them to their original polychrome. Despite these findings, the popular imagination still perceives these statues as lily white. This perception is largely due to cultural values and the influence of art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who propagated the idea of a "pure, marble-white Antiquity" and saw white marble classical sculpture as the embodiment of ideal beauty.[13][14]

Recent examples edit

In October 2023, the Musée Grévin in Paris draw criticism, and was accused of whitewashing, for it portrayal of the skin tone of Dwayne Johnson on its waxwork.[15]

Other uses of "whitewashing" in art edit

Within artistic materials and techniques, "whitewash" pertains to a matte white paint used by artists, commonly in the form of mineral pigments like zinc white and titanium white. These paints possess distinct properties and are employed for various artistic purposes. Zinc white, for instance, carries a cool blue tint, while titanium white leans toward a yellowish hue. The historical evolution of white paints, such as the traditional use of lead white, illustrates the complexities of achieving desired pigmentation while acknowledging potential material toxicity.[16] This artistic perspective on whitewashing diverges from broader societal and racial discussions.

Further reading edit

- Earle, T. F.; Lowe, K. J. P., eds. (2006). Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81582-6.

- Simons, Patricia (2022-03-01). "Race Matters: Black Andromeda in the Renaissance and in Contemporary Whitewashing". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 41 (3): 165–175. doi:10.1086/720926. ISSN 0737-4453.

- Siegal, Nina (2020-03-13). "Dutch Golden Age Art Wasn't All About White People. Here's the Proof". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- Blakely, Allison (2008-02-09). "The Black Presence in Pre-20th Century Europe: A Hidden History •". Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- Cook, Greg (2016-01-15). "Were Those Black 'Servants' In Dutch Old Master Paintings Actually Slaves?". www.wbur.org. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- Fracchia, Carmen (2024-01-05). "The African Presence in Iberian Art". Bulletin of Spanish Studies: 1–32. doi:10.1080/14753820.2023.2286749. ISSN 1475-3820.

See also edit

- Whitewashing in film – Controversial casting practice in the film industry

- Harlem Renaissance – African-American cultural movement in New York City in the 1920s

- African art

References edit

- ^ a b c d e Galer, Sophia Smith. "How black women were whitewashed by art". BBC. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Helligar, Jeremy (2020-09-14). "This Is What Whitewashing Really Means—and Why It's a Problem". Reader's Digest. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- ^ a b c Bedworth, Candy (2024-02-20). "Enslaved Black Models in European Art: Anonymous Objects?". DailyArt Magazine. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ a b "The outrageous neglect of African figures in art history | Art UK". artuk.org. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ^ a b Childs, Adrienne L. (2023-10-03). "The Black Figure in European Art". Realism Today. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ "Adrienne L Childs. com". adrienne-l-childs. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "In Depth: Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe | Princeton University Art Museum". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ a b Spicer, Joaneath. "Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe". hnanews.org. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (2012-11-08). "A Spectrum From Slaves to Saints". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ Baltimore, 600 N. Charles St; Usa, Md 21201. "Dr. Joaneath Spicer". CODART. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ House, Anna Swartwood (2020-07-17). "The long history of how Jesus came to resemble a white European". The Conversation. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Jackall, Yuriko (2021-11-23). "Titian's 'Perseus and Andromeda'". ART UK.

- ^ a b Bond, Sarah. "Whitewashing Ancient Statues: Whiteness, Racism And Color In The Ancient World". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ a b "Whitewashing Antiquity – Confluence". 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ "The Rock waxwork museum makes skin tone fix after criticism". BBC News. 2023-10-24. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "Whitewashing Art - History, Artists, Artworks". Arthive. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

External links edit

- "Mission Statement - People of Color in European Art History". medievalpoc. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- "Black people in European art". europeana. Retrieved 2024-04-27.