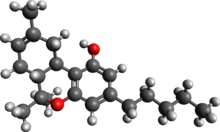

Δ-8-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-8-THC,[a] Δ8-THC) is a psychoactive cannabinoid found in the Cannabis plant.[1] It is an isomer of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-9-THC, Δ9-THC), the compound commonly known as THC, with which it co-occurs in hemp; natural quantities of ∆8-THC found in hemp are low. Psychoactive effects are similar to that of Δ9-THC, with central effects occurring by binding to cannabinoid receptors found in various regions of the brain.[2]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6a,7,10,10a-tetrahydrobenzo[c]chromen-1-ol

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.165.076 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H30O2 | |

| Molar mass | 314.5 g/mol |

| Density | 1.0±0.1 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 383.5±42.0 °C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Partial synthesis of ∆8-THC was published in 1941 by Roger Adams and colleagues at the University of Illinois. After the 2018 United States farm bill was signed, ∆8-THC products partially synthesized from industrial hemp experienced a rise in popularity; THC products have been sold in licensed recreational cannabis and medical cannabis industries within the United States in California, Pennsylvania, and medicinally licensed in Michigan and Oregon. According to a March 2024 study,[3] 11% of US twelfth graders have used ∆8-THC over the past 12 months.

Effects

edit∆8-THC is moderately less potent than Δ9-THC.[4][5] This means that while its effects are similar to that of Δ9-THC, it would take more ∆8-THC to achieve a comparable level of effect.

A 1973 study testing the effects of ∆8-THC in dogs and monkeys reported that a single oral dose of 9,000 milligrams per kilogram of body mass (mg/kg) was nonlethal in all dogs and monkeys studied.[6] The same study reported that the median lethal dose of ∆8-THC in rats was comparable to that of ∆9-THC.[6] Both isomers of THC have been found to cause a transient increase in blood pressure in rats,[7] although the effects of cannabinoids on the cardiovascular system are complex.[8] Animal studies indicate that ∆8-THC exerts many of its central effects by binding to cannabinoid receptors found in various regions of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cerebellum.[9][10]

Production

edit∆8-THC is typically synthesized from cannabidiol extracted from hemp,[11] as the natural quantities of ∆8-THC found in hemp are low. This is called semisynthesis or partial synthesis. The reaction often yields a mixture that contains other cannabinoids and unknown reaction by-products. As a result, most products sold as ∆8-THC are not actually pure ∆8-THC.[11] Little is known about the identity and the health effects of the impurities.[11] Some manufacturers of ∆8-THC may use household chemicals in the synthesis process, potentially introducing harmful contaminants.[12] In that sense, ∆8-THC can be called a "semisynthetic phytocannabinoid" or semisynthetic endocannabinoid, as it is obtained by (partial) chemical synthesis. It is not to be confused with the term synthetic cannabinoid, however.

Safety

editAs of 2022, the safety profile, including risks of psychosis and addiction after regular, long-term delta-8-THC use was unknown.[13]

As of 2022, there have been at least 104 adverse event reports made regarding ∆8-THC,[12] and at least two deaths associated with ∆8-THC products.[14] US national poison control centers received 2,362 exposure cases of delta-8 THC products between January 1, 2021, and February 28, 2022; 58% of these exposures involved adults, and 70% thought they required medical care.[12]

Pharmacology

editMechanism of action

editThe pharmacodynamic profile of ∆8-THC is similar to that of ∆9-THC.[4][5] It is a partial agonist of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors with about half the potency of ∆9-THC in most but not all measures of biological activity.[15][16][17] ∆8-THC has been reported to have a Ki value of 44 ± 12 nM at the CB1 receptor and 44 ± 17 nM at the CB2 receptor.[18] These values are higher than those typically reported for ∆9-THC (CB1 Ki = 40.7 nM) at the same receptors, indicating that ∆8-THC binds to cannabinoid receptors less efficiently than ∆9-THC.[19]

Pharmacokinetics

editThe pharmacokinetic profile of ∆8-THC is also similar to that of ∆9-THC.[4][5] Following ingestion in humans, hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes including CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 first convert ∆8-THC into 11-hydroxy-Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-OH-Δ8-THC).[20][21] Next, dehydrogenase enzymes convert 11-OH-Δ8-THC into 11-nor-Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid (11-nor-Δ8-THC-9-COOH, also known as Δ8-THC-11-oic acid).[21][22] Finally, Δ8-THC-11-oic acid undergoes glucuronidation by glucuronidase enzymes to form 11-nor-Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid glucuronide (Δ8-THC-COOH-glu),[21][22] which is then excreted in the urine.[23][24]

Physical and chemical properties

edit∆8-THC is a tricyclic terpenoid. Although it has the same chemical formula as ∆9-THC, one of its carbon-carbon double bonds is located in a different position.[4] In ∆8-THC, the double bond is between the eighth and ninth carbons in structure, while in Δ9-THC, the double bond is between the ninth and tenth carbons in structure.

This difference in structure increases the chemical stability of ∆8-THC relative to ∆9-THC, lengthening shelf life and allowing the compound to resist undergoing oxidation to cannabinol over time.[15] Like other cannabinoids, ∆8-THC is very lipophilic (log P = 7.4[25]). It is an extremely viscous, colorless oil at room temperature.[26]

While ∆8-THC is naturally found in plants of the Cannabis genus,[1] this compound can also be produced in an industrial or laboratory setting by acid-catalyzed isomerization of cannabidiol.[27][28][29] Solvents that may be used during this process include dichloromethane, toluene, and hexane.[29] Various Brønsted or Lewis acids that may be used to facilitate this isomerization include tosylic acid, indium(III) triflate, trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate, hydrochloric acid, and sulfuric acid.[29] Because it is possible for chemical contaminants to be generated during the process of converting CBD to ∆8-THC, such as Δ10-THC, 9-OH-HHC and other side products, concern has been raised about the safety of untested or impure ∆8-THC products.[30]

The ongoing controversy regarding the legal status of ∆8-THC in the U.S. () is complicated by chemical nomenclature. According to a 2019 literature review published in Clinical Toxicology, the term synthetic cannabinoid typically refers to a full agonist of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors.[31] According to the review, the following is stated:

"The psychoactive (and probably the toxic) effects of synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists are likely due to their action as full receptor agonists and their greater potency at CB1 receptors."

However, ∆8-THC and ∆9-THC are partial agonists of cannabinoid receptors.[16] They are less potent than many synthetic cannabinoids.[32] It has not been definitively proven if full agonism is the reason for the greater incidence of adverse reactions to synthetic cannabinoids since ∆9-THC has been shown to act as a full CB1 agonist on specific CB1 receptors located in the hippocampus section of the brain.[33] Furthermore, the synthetic cannabinoid EG-018 acts as a partial agonist.[34] The classical cannabinoid structure is that of a dibenzopyran structure. This group includes THC. THC interacts with a different spot inside of the CB1 receptor than synthetic cannabinoid such JWH-018. This may explain the differences in adverse reactions to synthetic cannabinoids.[35]

History

editThe partial synthesis of ∆8-THC was published in 1941 by Roger Adams and colleagues at the University of Illinois.[36] In 1942, the same research group studied its physiological and psychoactive effects after oral dosing in human volunteers.[37] Total syntheses of ∆8-THC were achieved by 1965.[38] In 1966, the chemical structure of ∆8-THC isolated from cannabis was characterized using modern methods by Richard L. Hively, William A. Mosher, and Friedrich W. Hoffmann at the University of Delaware.[39] A stereospecific synthesis of ∆8-THC from olivetol and verbenol was reported by Raphael Mechoulam and colleagues at the Weizmann Institute of Science in 1967.[40] ∆8-THC was often referred to as "Delta-6-THC" (Δ6-THC) in early scientific literature, but this name is no longer conventional among most authors.[41]

Regulation

editUnited States

editFederal law

editIn 1937, ∆9-THC was effectively made illegal with the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act, which made growing cannabis require a tax stamp. In 1970, the Marihuana Tax Act was superseded and replaced with the Controlled Substances Act (or CSA).[42] The CSA replaced "[a] patchwork of regulatory, revenue, and criminal measures"[43] relating to drug control with a "comprehensive regulatory regime".[44]

As of 2024, 24 states have legalized cannabis, with others having reduced penalties.[45] Section 10113 of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (2018 Farm Bill), amended the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946, and added a new subtitle G related to hemp.[46] Under section 297A of that subtitle, is the definition of hemp as used in federal law:

The term "hemp" means the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.

— Section 297A of the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 (7 U.S.C. 1639o)

In October 2020, the DEA Interim Final Rule[47] addressed synthetic cannabinoids. Some believed that this also applied to ∆8-THC products and other hemp derivatives addressed by the Farm Bill.[48] The legality of ∆8-THC in the United States continues to evolve as of 2021.[11]

FDA

edit∆8-THC has not been evaluated or approved by the FDA. Consequently, Δ-8-tetrahydrocannabinol is not recognized under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act as safe and effective for any use.[12] The FDA has taken action against businesses that have illegally marketed ∆8-THC for therapeutic use.[12] The FDA has also taken action against businesses that sold ∆8-THC in forms that closely resemble (typically non-psychoactive) food products such as chips or cookies.[12]

Individual states

editWhile many jurisdictions have not arrested significant numbers of people for ∆8-THC, some people have been arrested and charged, leading to confusion as to its legal status in those states.[49][50][51][52]

In 2021, one store owner in Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin was facing a sentence of up to 50 years for allegedly selling ∆8-THC products with illegal amounts of ∆9-THC.[53] Other raids and arrests have happened due to the ∆9-THC content of these products in North Carolina, and Texas, among other places.[54][55][56] In 2022, Catoosa County, Georgia Sheriff Sisk announced to prosecute stores distributing ∆8-THC with non-compliant ∆9-THC levels: "The products the sheriffs office has purchased and tested all contain significant levels of ∆9. [We have the] evidence needed to move forward with prosecution and seizures."[57] There are also issues related to incidental manufacture of ∆9 THC, as ∆9 is produced as an intermediate product in the process of acid catalyzed ring closure of cannabidiol.[58]

∆8-THC products have been sold in licensed, regulated recreational cannabis and medical cannabis industries within the United States including California and Pennsylvania's licensed, regulated medical cannabis system since 2020. Both Michigan and the state of Oregon have regulated Delta-8-THC products sold under their regulated cannabis system.[59]

Federal Litigation

editThe first case before a United States courts of appeals relating to the legality of ∆8-THC was AK Futures v. Boyd St. Distro (2022), a patent lawsuit where the 9th Circuit found that ∆8-THC products qualified for patent protection. The legality of ∆8-THC was addressed briefly in dicta, where the court held the products subject of the litigation were lawful.[60]

The ruling of the 9th Circuit is only binding to the states within that circuit, and other federal courts have reached differing conclusions. At the federal district court level, the United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas reached a similar conclusion to the 9th Circuit,[61] yet the United States District Court for the District of Wyoming found that ∆8-THC was not legal and the 2018 Farm Bill did not imply for preemption of state laws.[62]

Products and prevalence of use

editCommon Delta-8 products range from bulk quantities of unrefined distillate to prepared cannabis edibles and atomizer cartridges.[63][64] In the US, they are usually marketed as legal alternatives to their ∆9-THC counterparts.[65]

∆8-THC products partially synthesized from industrial hemp experienced a rise in popularity in the US following the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill.[66] This led to it being sold by a diverse range of retailers, including head shops, smoke shops, vape shops, dispensaries, gas stations, and convenience stores.[67][68]

In March 2024, a study of self-reported prevalence of Δ8-THC use among US twelfth graders was published: Of those reporting Δ8-THC use, 35% had used it at least 10 times in the past 12 months. Consumption was lower in Western than Southern and in states, where Δ8-THC was regulated versus not regulated.[69]

Research

editAlthough it is a minor constituent of medical cannabis, no large clinical studies have been conducted on delta-8-THC alone as of 2022.[70] One study (ongoing as of November 2023) is focused on determining the degree of pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic similarity between ∆8-THC and ∆9-THC.[71]

See also

edit- Ajulemic acid

- Cannabinoid

- Cannabis (drug)

- delta-3-Tetrahydrocannabinol

- delta-4-Tetrahydrocannabinol

- delta-7-Tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-5-tetrahydrocannabinol)

- delta-10-Tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-2-tetrahydrocannabinol)

- delta-6-Cannabidiol

- 11-Hydroxy-Delta-8-THC

- Endocannabinoid system

- Hexahydrocannabinol

- 7,8-Dihydrocannabinol

- Tetrahydrocannabinol

- Tetrahydrocannabutol

- Tetrahydrocannabiphorol

- THC-O-acetate

- THC-O-phosphate

References

edit- ^ a b Qamar S, Manrique YJ, Parekh HS, Falconer JR (May 2021). "Development and Optimization of Supercritical Fluid Extraction Setup Leading to Quantification of 11 Cannabinoids Derived from Medicinal Cannabis". Biology. 10 (6): 481. doi:10.3390/biology10060481. PMC 8227983. PMID 34071473.

- ^ Geci M, Scialdone M, Tishler J (2023). "The Dark Side of Cannabidiol: The Unanticipated Social and Clinical Implications of Synthetic Δ8-THC". Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 8 (2): 270–282. doi:10.1089/can.2022.0126. PMC 10061328. PMID 36264171.

- ^ Harlow AF, Miech RA, Leventhal AM (12 March 2024). "Adolescent Δ8-THC and Marijuana Use in the US". JAMA. 331 (10): 861–865. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.0865. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 10933714. PMID 38470384.

- ^ a b c d Razdan RK (1984). "Chemistry and Structure-Activity Relationships of Cannabinoids: An Overview". The Cannabinoids: Chemical, Pharmacologic, and Therapeutic Aspects. pp. 63–78. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-044620-9.50009-9. ISBN 978-0-12-044620-9.

- ^ a b c Hollister LE, Gillespie HK (May 1973). "Delta-8- and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol comparison in man by oral and intravenous administration". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 14 (3): 353–7. doi:10.1002/cpt1973143353. PMID 4698563. S2CID 41556421.

- ^ a b Thompson GR, Rosenkrantz H, Schaeppi UH, Braude MC (July 1973). "Comparison of acute oral toxicity of cannabinoids in rats, dogs and monkeys". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 25 (3): 363–72. doi:10.1016/0041-008x(73)90310-4. PMID 4199474.

- ^ Adams MD, Earnhardt JT, Dewey WL, Harris LS (March 1976). "Vasoconstrictor actions of delta8- and delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rat". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 196 (3): 649–56. PMID 4606.

- ^ Richter JS, Quenardelle V, Rouyer O, Raul JS, Beaujeux R, Gény B, et al. (29 May 2018). "A Systematic Review of the Complex Effects of Cannabinoids on Cerebral and Peripheral Circulation in Animal Models". Frontiers in Physiology. 9: 622. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00622. PMC 5986896. PMID 29896112.

- ^ Charalambous A, Marciniak G, Shiue CY, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, Wolf AP, et al. (November 1991). "PET studies in the primate brain and biodistribution in mice using (-)-5'-18F-delta 8-THC". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 40 (3): 503–7. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90354-5. PMID 1666914. S2CID 140208679.

- ^ Tripathi HL, Vocci FJ, Brase DA, Dewey WL (1987). "Effects of cannabinoids on levels of acetylcholine and choline and on turnover rate of acetylcholine in various regions of the mouse brain". Alcohol and Drug Research. 7 (5–6): 525–32. PMID 3620017. INIST 7401152.

- ^ a b c d Britt E. Erickson (29 August 2021). "Delta-8-THC craze concerns chemists: Unidentified by-products and lack of regulatory oversight spell trouble for cannabis products synthesized from CBD". Chemical & Engineering News.

- ^ a b c d e f "5 Things to Know about Delta-8 Tetrahydrocannabinol – Delta-8 THC". US Food and Drug Administration. 25 March 2022.

- ^ Dotson S, Johnson-Arbor K, Schuster RM, Tervo-Clemmens B, Evins AE (2022). "Unknown risks of psychosis and addiction with delta-8-THC: A call for research, regulation, and clinical caution". Addiction. 117 (9): 2371–2373. doi:10.1111/add.15873. ISSN 0965-2140. PMID 35322899. S2CID 247629994.

- ^ "Mother charged with murder after child dies from ingesting delta-8 THC gummies, officials say". KIRO 7 News Seattle. 21 October 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ a b Abrahamov A, Abrahamov A, Mechoulam R (May 1995). "An efficient new cannabinoid antiemetic in pediatric oncology". Life Sciences. 56 (23–24): 2097–102. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(95)00194-b. PMID 7776837.

- ^ a b Walter L, Stella N (March 2004). "Cannabinoids and neuroinflammation". British Journal of Pharmacology. 141 (5): 775–85. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705667. PMC 1574256. PMID 14757702.

- ^ Morales P, Hurst DP, Reggio PH (2017). "Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids: A Complex Picture". Phytocannabinoids. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Vol. 103. Springer. pp. 103–131. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_4. ISBN 978-3-319-45539-6. PMC 5345356. PMID 28120232.

- ^ Bow EW, Rimoldi JM (January 2016). "The Structure-Function Relationships of Classical Cannabinoids: CB1/CB2 Modulation". Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry. 8: 17–39. doi:10.4137/PMC.S32171. PMC 4927043. PMID 27398024.

- ^ Pertwee RG (January 2008). "The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442. PMC 2219532. PMID 17828291.

- ^ Stout SM, Cimino NM (February 2014). "Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 46 (1): 86–95. doi:10.3109/03602532.2013.849268. PMID 24160757. S2CID 29133059.

- ^ a b c Villamor JL, Bermejo AM, Tabernero MJ, Fernandez P, Sanchez I (December 1998). "GC/MS Determination of 11-Nor-9-Carboxy-Δ 8 -tetrahydrocannabinol in Urine from Cannabis Users". Analytical Letters. 31 (15): 2635–2643. doi:10.1080/00032719808005332.

- ^ a b Valiveti S, Hammell DC, Earles DC, Stinchcomb AL (June 2005). "LC-MS method for the estimation of delta8-THC and 11-nor-delta8-THC-9-COOH in plasma". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 38 (1): 112–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2004.11.055. PMID 15907628.

- ^ Harvey DJ, Brown NK (November 1991). "Comparative in vitro metabolism of the cannabinoids". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 40 (3): 533–40. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90359-A. PMID 1806943. S2CID 25827210.

- ^ Mechoulam R, BenZvi Z, Agurell S, Nilsson IM, Nilsson JL, Edery H, et al. (October 1973). "Delta 6-tetrahydrocannabinol-7-oic acid, a urinary delta 6-THC metabolite: isolation and synthesis". Experientia. 29 (10): 1193–5. doi:10.1007/BF01935065. PMID 4758913. S2CID 27021897.

- ^ Thomas BF, Compton DR, Martin BR (November 1990). "Characterization of the lipophilicity of natural and synthetic analogs of ∆9-THC and its relationship to pharmacological potency". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 255 (2): 624–30. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.968.4912. PMID 2173751.

- ^ Rosenkrantz H, Thompson GR, Braude MC (July 1972). "Oral and parenteral formulations of marijuana constituents". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 61 (7): 1106–12. doi:10.1002/jps.2600610715. PMID 4625586.

- ^ Golombek P, Müller M, Barthlott I, Sproll C, Lachenmeier DW (June 2020). "Conversion of Cannabidiol (CBD) into Psychotropic Cannabinoids Including Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): A Controversy in the Scientific Literature". Toxics. 8 (2): 41. doi:10.3390/toxics8020041. PMC 7357058. PMID 32503116.

- ^ Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R (January 1966). "Hashish—VII". Tetrahedron. 22 (4): 1481–1488. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99446-3.

- ^ a b c Marzullo P, Foschi F, Coppini DA, Fanchini F, Magnani L, Rusconi S, et al. (October 2020). "Cannabidiol as the Substrate in Acid-Catalyzed Intramolecular Cyclization". Journal of Natural Products. 83 (10): 2894–2901. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00436. PMC 8011986. PMID 32991167.

- ^ Erickson BE (30 August 2021). "Delta-8-THC craze concerns chemists". Chemical & Engineering News. 99 (31).

- ^ Potts AJ, Cano C, Thomas SH, Hill SL (February 2020). "Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists: classification and nomenclature". Clinical Toxicology. 58 (2): 82–98. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1661425. PMID 31524007. S2CID 202581071.

- ^ Kelly BF, Nappe TM (2021). "Cannabinoid Toxicity". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29489164.

- ^ Laaris N, Good CH, Lupica CR (2010). "Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol is a full agonist at CB1 receptors on GABA neuron axon terminals in the hippocampus". Neuropharmacology. 59 (1–2): 121–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.013. PMC 2882293. PMID 20417220.

- ^ Gamage TF, Barrus DG, Kevin RC, Finlay DB, Lefever TW, Patel PR, et al. (June 2020). "In vitro and in vivo pharmacological evaluation of the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist EG-018". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 193: 172918. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172918. PMC 7239729. PMID 32247816.

- ^ Huffman JW, Padgett LW (31 May 2005). "Recent developments in the medicinal chemistry of cannabimimetic indoles, pyrroles and indenes". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 12 (12): 1395–411. doi:10.2174/0929867054020864. PMID 15974991.

- ^ Adams R, Cain CK, McPhee WD, Wearn RB (August 1941). "Structure of Cannabidiol. XII. Isomerization to Tetrahydrocannabinols 1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 63 (8): 2209–2213. doi:10.1021/ja01853a052.

- ^ Adams R (November 1942). "Marihuana: Harvey Lecture, February 19, 1942". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 18 (11): 705–30. PMC 1933888. PMID 19312292.

- ^ Mechoulam R (June 1970). "Marihuana chemistry". Science. 168 (3936): 1159–66. Bibcode:1970Sci...168.1159M. doi:10.1126/science.168.3936.1159. PMID 4910003.

- ^ Hively RL, Mosher WA, Hoffmann FW (April 1966). "Isolation of trans-delta-tetrahydrocannabinol from marijuana". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 88 (8): 1832–3. doi:10.1021/ja00960a056. PMID 5942992.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Braun P, Gaoni Y (August 1967). "A stereospecific synthesis of (-)-delta 1- and (-)-delta 1(6)-tetrahydrocannabinols". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 89 (17): 4552–4. doi:10.1021/ja00993a072. PMID 6046550.

- ^ Pertwee RG (January 2006). "Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years". British Journal of Pharmacology. 147 (Suppl 1): S163-71. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406. PMC 1760722. PMID 16402100.

- ^ Sullum J (14 July 2024). "Congress 'can regulate virtually anything'". Reason.com. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Bonnie R, Whitebread II C (1975). "The Marihuana Conviction: A History of Marihuana Prohibition in the United States". The American Historical Review. doi:10.1086/ahr/80.4.1057. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005)

- ^ Russell K (26 March 2024). "Where is marijuana legal in the US? A state-by-state guide". NBC4 Washington. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "The Farm Bill, hemp legalization and the status of CBD: An explainer". Brookings. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Federal Register (21 August 2020). "Implementation of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018.A Rule by the Drug Enforcement Administration". Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ King S (18 January 2021). "How Some THC Is Legal — For Now". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Stewart J (13 October 2021). "Investigation into sale of THC products leads to arrests". Northwest Georgia News. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Rogers C (11 February 2021). "Port Lavaca smoke shop owner turns self in, retains Austin cannabis law attorney". The Victoria Advocate. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Jones K (23 March 2021). "Upstate police seize Delta-8 THC products from vape shop, owner argues they're legal". WYFF. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Matsuoka S (27 October 2021). "GSO hemp shop owners say police wrongly searched, seized legal THC products". Triad City Beat. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Sachs J (20 December 2021). "CBD store owner faces felony charges after raid". FOX6 News Milwaukee. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "GSO hemp shop owners say police wrongly searched, seized legal THC products". Triad City Beat. 27 October 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Pelkey S (28 March 2022). "Asheboro PD VICE/Narcotics Team Cracks Down on Illegal THC Devices At Local Vape Shops". Randolph News Now. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Vaughn J. "Texas Hemp Shop Owners Often Find Themselves in a Legal Haze". Dallas Observer. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Maggiore S (14 March 2022). "Sheriff to Catoosa County smoke shop owners: Your Delta 8 products violate state law". WFLI. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Geci M, Scialdone M, Tishler J (19 October 2022). "The Dark Side of Cannabidiol: The Unanticipated Social and Clinical Implications of Synthetic Δ8-THC". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 8 (2): 270–282. doi:10.1089/can.2022.0126. ISSN 2578-5125. PMC 10061328. PMID 36264171.

- ^ Kaufman A. "Is delta-8 THC legal? Where (and why) the hemp product skirts marijuana laws". USA TODAY. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Custer M. "9th Circ. Delta-8 Ruling Was Probably A Blip, Not A Landmark". Law360. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Federal Judge blocks Delta 8 ban in Arkansas, trial date set for next year". 5newsonline.com. 11 September 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Court dismisses Delta-8 lawsuit, preserving the ban that outlaws it". Wyoming Public Media. 24 August 2024. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Guo W, Vrdoljak G, Liao VC, Moezzi B (21 June 2021). "Major Constituents of Cannabis Vape Oil Liquid, Vapor and Aerosol in California Vape Oil Cartridge Samples". Frontiers in Chemistry. 9. Front Chem. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.694905. PMC 8333608. PMID 34368078.

- ^ Tadlock C (7 April 2023). "Cannabis sales have buyers, sellers on a different high". thecharlottepost.com. The Charlotte Post. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

Located at vape shops, convenience stores and even gas stations, Delta-8 is well-accessible to consumers. Products are available in different forms, including gummies, chocolate, vaping cartridges, infused drinks and even breakfast cereal.

- ^ Farah T (23 September 2020). "Delta-8-THC Promises to Get You High Without the Paranoia or Anxiety". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ LoParco C, Rossheim M, Walters S, Zhou Z, Olsson S, Sussman S (29 January 2023). "Delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol: a scoping review and commentary". Addiction. 118 (6). Society for the Study of Addiction: 1011–1028. doi:10.1111/add.16142. PMID 36710464. S2CID 256388694.

- ^ Schaefer B (10 February 2023). "Attorney General William Tong warns vape shops about delta-8 THC products". wtnh.com. Nexstar Media. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

We're seeing delta 8 products being sold across the state, everywhere we went to every vape shop we visited and gas stations as well,

- ^ Muckle, Shauna (July 6, 2023). St. Petersburg's '420' shop promises to get you high. Is it legal?. Tampa Bay Times. "from gas stations to smoke and vape shops to grocery stores and dispensaries"

- ^ Harlow AF, Miech RA, Leventhal AM (12 March 2024). "Adolescent Δ8-THC and Marijuana Use in the US". JAMA. 331 (10): 861–865. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.0865. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 10933714. PMID 38470384.

- ^ Tagen M, Klumpers LE (2022). "Review of delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ 8 -THC): Comparative pharmacology with Δ 9 -THC". British Journal of Pharmacology. 179 (15): 3915–3933. doi:10.1111/bph.15865. ISSN 0007-1188. PMID 35523678. S2CID 248554356.

- ^ "CTG Labs - NCBI". clinicaltrials.gov. 20 October 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

Notes

edit- ^ Commonly spoken as "delta-8 THC", or just "delta 8".