The Cypriot or Cypriote syllabary (also Classical Cypriot Syllabary) is a syllabic script used in Iron Age Cyprus, from about the 11th to the 4th centuries BCE, when it was replaced by the Greek alphabet. It has been suggested that the script remained in use as late as the 1st century BC.[1] A pioneer of that change was King Evagoras of Salamis. It is thought to be descended from the Cypro-Minoan syllabary, itself a variant or derivative of Linear A. Most texts using the script are in the Arcadocypriot dialect of Greek, but also one bilingual (Greek and Eteocypriot) inscription was found in Amathus.

| Cypriot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Syllabary

|

Time period | 11th–4th centuries BCE |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Arcadocypriot Greek, Eteocypriot |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Linear A

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cprt (403), Cypriot syllabary |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cypriot |

| U+10800–U+1083F | |

Origin

editIt is thought that the Cypriot syllabary is derived from the Cypro-Minoan syllabary; the latter is thought to be derived from the Linear A script, and certainly belongs to the circle of Aegean scripts. The most obvious change is the disappearance of ideograms, which were frequent and represented a significant part of Linear A. The earliest inscriptions are found on clay tablets. Parallel to the evolution of cuneiform, the signs soon became simple patterns of lines. There is no evidence of a Semitic influence due to trade, but this pattern seemed to have evolved as the result of habitual use.[2]

Structure

editThe structure of the Cypriot syllabary is very similar to that of Linear B. This is due to their common origin and underlying language (albeit different dialects).[2] The Cypriot script contains 56 signs.[3] Each sign generally stands for a syllable in the spoken language: e.g. ka, ke, ki, ko, ku. Hence, it is classified as a syllabic writing system.[4] Because each sign stands for an open syllable (CV) rather than a closed one (CVC), the Cypriot syllabary is also an 'open' syllabary.[3]

| -a | -e | -i | -o | -u | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐠀 | 𐠁 | 𐠂 | 𐠃 | 𐠄 | |

| w- | 𐠲 | 𐠳 | 𐠴 | 𐠵 | |

| z- | 𐠼 | 𐠿 | |||

| j- | 𐠅 | 𐠈 | |||

| k-, g-, kh- | 𐠊 | 𐠋 | 𐠌 | 𐠍 | 𐠎 |

| l- | 𐠏 | 𐠐 | 𐠑 | 𐠒 | 𐠓 |

| m- | 𐠔 | 𐠕 | 𐠖 | 𐠗 | 𐠘 |

| n- | 𐠙 | 𐠚 | 𐠛 | 𐠜 | 𐠝 |

| ks- | 𐠷 | 𐠸 | |||

| p-, b-, ph- | 𐠞 | 𐠟 | 𐠠 | 𐠡 | 𐠢 |

| r- | 𐠣 | 𐠤 | 𐠥 | 𐠦 | 𐠧 |

| s- | 𐠨 | 𐠩 | 𐠪 | 𐠫 | 𐠬 |

| t-, d-, th- | 𐠭 | 𐠮 | 𐠯 | 𐠰 | 𐠱 |

To see the glyphs above, you must have a compatible font installed, and your web browser must support Unicode characters in the U+10800–U+1083F range.

Differences between Cypriot syllabary and Linear B

editThe main difference between the two lies not in the structure of the syllabary but the use of the symbols. Final consonants in the Cypriot syllabary are marked by a final, silent e. For example, final consonants, n, s, and r are noted by using ne, re, and se. Groups of consonants are created using extra vowels. Diphthongs such as ae, au, eu, and ei are spelled out completely. However, nasal consonants that occur before another consonant are omitted completely.[2]

Compare Linear B 𐀀𐀵𐀫𐀦 (a-to-ro-qo, reconstructed as *[án.tʰroː kʷos]) to Cypriot 𐠀𐠰𐠦𐠡𐠩 (a-to-ro-po-se, read right-to-left), both forms related to Attic Greek: ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos) "human".

One other minor difference involves the representation of the manner of articulation. In the Linear B script, liquid sounds /l/ and /r/ are covered by one series, while there are separate series for the dentals /d/ and /t/. In the Cypriot syllabary, /d/ and /t/ are combined, whereas /l/ and /r/ are distinct.[4]

Paleography

editThere are minor differences in the forms of the signs used in different sites.[2] However, the syllabary can be subdivided into two different subtypes based on area: the "Common" and the South-Western or "Paphian".[4]

Decipherment

editThe script was deciphered in the 19th century by George Smith due to the Idalion bilingual. Egyptologist Samuel Birch (1872), the numismatist Johannes Brandis (1873), the philologists Moritz Schmidt, Wilhelm Deecke, Justus Siegismund (1874) and the dialectologist H. L. Ahrens (1876) also contributed to decipherment.[5]

Corpus

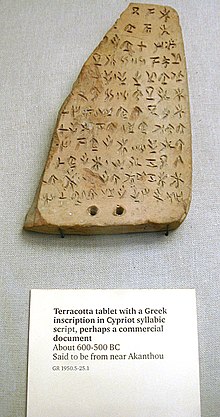

editAbout 1,000 inscriptions in the Cypriot syllabary have been found throughout many different regions. However, these inscriptions vary greatly in length and credibility.[4] Most inscriptions found are dated to be around the 6th century. There are no inscriptions known to be before the 8th century. Most of the tablets found are from funerary monuments and contained merely names of the deceased. A few dedicatory inscriptions were also found but of very little contribution to decipherment. The most important tablets are mainly found in Enkomi and Paphos.

Efforts to collect and publish the known corpus began in the 1800s.[6][7][8] In the 1900s the work was taken up by T. B. Mitford and Olivier Masson.[9] Over the years a number of inaccuracies and duplications crept into the collects corpus. In 2015, Massimo Perna published a consolidated and corrected corpus totaling 1,397 inscriptions.[10]

Enkomi

editThe earliest dated inscription from Cyprus was discovered at Enkomi in 1955. It was a part of a thick clay tablet with only three lines of writing. Epigraphers immediately saw a resemblance. Because the date of the fragment was found to be around 1500 BCE, considerably earlier than Linear B, linguists determined that the Cypriot syllabary was derived from Linear A and not Linear B. Several other fragments of clay tablets were also found in Enkomi. They date to a later period, around the late 13th or 12th century BCE. The script found on these tablets has considerably evolved and the signs have become simple patterns of lines. Linguists named this new script as Cypro-Minoan syllabary.[2]

Idalium

editIdalium was an ancient city in Cyprus, in modern Dali, Nicosia District. The city was founded on the copper trade in the 3rd millennium BCE. Its name in the 8th century BCE was "Ed-di-al" as it appears on the Sargon Stele of 707 BCE. From this area, archeologists found many of the later Cypriot syllabic scripts. In fact, Idalium held the most significant contribution to the decipherment of Cypriot syllabary – the Tablet of Idalium. It is a large bronze tablet with long inscriptions on both sides.[2] The Tablet of Idalium is dated to about 480–470 BCE. Excluding a few features in morphology and vocabulary, the text is a complete and well-understood document. It details a contract made by the king Stasicyprus and the city of Idalium with the physician Onasilus and his brothers.[4] As payment for the physicians' care for wounded warriors during a Persian siege of the city, the king promises them certain plots of land. This agreement is put under the protection of the goddess Athena.[4]

Recent discoveries

editRecent discoveries include a small vase dating back to the beginning of the 5th century BCE and a broken marble fragment in the Paphian (Paphos) script. The vase is inscribed on two sides, providing two lists of personal names with Greek formations. The broken marble fragment describes a fragment of an oath. This inscription often mentions King Nicocles, the last king of Paphos and includes some important words and expressions.[4] Four inscribed objects were found in the British Museum stores, a silver cup from Kourion, a White Ware jug, and two limestone tablet fragments.[11]

The number of discoveries of new inscriptions has increased. However, most of the new discoveries have been short, or bear only a few signs. One example is a small clay ball.[2]

Unicode

editThe Cypriot syllabary was added to the Unicode Standard in April 2003 with the release of version 4.0.

The Unicode block for Cypriot is U+10800–U+1083F. The Unicode block for the related Aegean Numbers is U+10100–U+1013F.

| Cypriot Syllabary[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1080x | 𐠀 | 𐠁 | 𐠂 | 𐠃 | 𐠄 | 𐠅 | 𐠈 | 𐠊 | 𐠋 | 𐠌 | 𐠍 | 𐠎 | 𐠏 | |||

| U+1081x | 𐠐 | 𐠑 | 𐠒 | 𐠓 | 𐠔 | 𐠕 | 𐠖 | 𐠗 | 𐠘 | 𐠙 | 𐠚 | 𐠛 | 𐠜 | 𐠝 | 𐠞 | 𐠟 |

| U+1082x | 𐠠 | 𐠡 | 𐠢 | 𐠣 | 𐠤 | 𐠥 | 𐠦 | 𐠧 | 𐠨 | 𐠩 | 𐠪 | 𐠫 | 𐠬 | 𐠭 | 𐠮 | 𐠯 |

| U+1083x | 𐠰 | 𐠱 | 𐠲 | 𐠳 | 𐠴 | 𐠵 | 𐠷 | 𐠸 | 𐠼 | 𐠿 | ||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Aegean Numbers[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1010x | 𐄀 | 𐄁 | 𐄂 | 𐄇 | 𐄈 | 𐄉 | 𐄊 | 𐄋 | 𐄌 | 𐄍 | 𐄎 | 𐄏 | ||||

| U+1011x | 𐄐 | 𐄑 | 𐄒 | 𐄓 | 𐄔 | 𐄕 | 𐄖 | 𐄗 | 𐄘 | 𐄙 | 𐄚 | 𐄛 | 𐄜 | 𐄝 | 𐄞 | 𐄟 |

| U+1012x | 𐄠 | 𐄡 | 𐄢 | 𐄣 | 𐄤 | 𐄥 | 𐄦 | 𐄧 | 𐄨 | 𐄩 | 𐄪 | 𐄫 | 𐄬 | 𐄭 | 𐄮 | 𐄯 |

| U+1013x | 𐄰 | 𐄱 | 𐄲 | 𐄳 | 𐄷 | 𐄸 | 𐄹 | 𐄺 | 𐄻 | 𐄼 | 𐄽 | 𐄾 | 𐄿 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mitford, T. B. (1950). "Kafizin and the Cypriot Syllabary". The Classical Quarterly. 44 (3–4): 97–106.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chadwick, John (1987). Linear B and Related Scripts. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06019-7.

- ^ a b Robinson, Andrew (2002). Lost Languages. New York. ISBN 978-0641699597.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Mitford, T. B.; Masson, Olivier (1982). "The Cypriot syllabary". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–82. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521234474.005. ISBN 978-1139054300.

- ^ Cannavò, Anna (2021). "Cipro-sillabico - (IX - II sec. a.C.)". Mnamon: Ancient writing systems in the Mediterranean (in Italian). Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. doi:10.25429/sns.it/lettere/mnamon002. ISBN 978-88-7642-719-0.

- ^ Luynes, Honoré d'Albert (1852). Numismatique et inscriptions chypriotes. Paris: Typographie Plon Freres.

- ^ Schmidt, M. (1876). Sammlung kyprischer Inschriften in epichorischer Schrift. Jena: Verlag von Hermann Dufft.

- ^ Deecke, W. (1884). "Die griechisch-kyprischen Inschriften in epichorischer Schrift". In Collitz, H.; Bechtel, F. (eds.). Sammlung der griechischen Dialekt-Inschriften. Vol. l. Göttingen.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bazemore, Georgia Bonny (2001). "Cypriote Sylllabic Epigraphy: The Need for Critical Re-examination of the Corpus". Kadmos. 40 (1): 67–88. doi:10.1515/kadm.2001.40.1.67. S2CID 162399752.

- ^ Perna, Massimo (2015). "Corpus of Cypriote syllabic inscriptions of the 1st millennium BC". Kyprios Character. History, Archaeology & Numismatics of Ancient Cyprus.

- ^ Kiely, Thomas; Perna, Massimo (2011). "Four Unpublished Inscriptions in Cypriot Syllabic Script in the British Museum". Kadmos. 49 (1): 93–116. doi:10.1515/kadmos.2010.005. S2CID 162345890.

Bibliography

edit- Best, Jan; Woudhuizen, Fred, eds. (1988), Ancient Scripts from Crete and Cyprus, Leiden: Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004673366, ISBN 978-90-04-08431-5, S2CID 160361420

- Egetmeyer, Markus (1992). Wörterbuch zu den Inschriften im kyprischen Syllabar. Berlin: de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110853520. ISBN 9783110122701.

- Heubeck, Alfred (1979). Schrift. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 54–64. ISBN 9783525254233.

- Hintze, Almut (1993). A Lexicon to the Cyprian Syllabic Inscriptions. Hamburg: Buske.

- Masson, Olivier; Mitford, Terence B. (1983). Les Inscriptions chypriotes syllabiques. Paris: Boccard.

- Reece, Steve (2000). "The Cypriot Syllabaries". In Speake, Graham (ed.). Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 1587–1588.

- Smith, Joanna S., ed. (2002). Script and seal use on Cyprus in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Archaeological Institute of America. ISBN 978-0960904273.

- Steele, Philippa M (2014). "The /d/, /t/, /l/ and /r/ series in Linear A and B, Cypro-Minoan and the Cypriot Syllabary". Pasiphae. 8: 189–196.

- Steele, Philippa M. (2013a). A Linguistic History of Ancient Cyprus: The non-Greek languages, and their relations with Greek, c. 1600–300 BC. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107337558. ISBN 9781107042865.

- Steele, Philippa M. (2013b). Steele, Philippa M. (ed.). Syllabic writing in Cyprus and its context. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139208482. ISBN 9781108442343.

- Steele, Philippa M. (2018). Writing and Society in Ancient Cyprus. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316729977. ISBN 9781107169678. S2CID 166103644.