The Asante Empire was governed by an elected monarch with its political power centralised. The entire government was a federation. By the 19th century, the Empire had a total population of 3 million.[1] The Asante society was matrilineal as most families were extended and were headed by a male elder who was assisted by a female elder. Asante twi was the most common and official language. At its peak from the 18th–19th centuries, the Empire extended from the Komoé River (Ivory Coast) in the West to the Togo Mountains in the East.[2]

The king and the aristocracy were the highest social class in the Asante society. Commoners were below the aristocracy with slaves forming the lowest social order. The Asante celebrated various ceremonies which were compulsory for communal participation. Festivals served as a means of promoting unity, remembering the ancestors and for thanksgiving. There was the belief in a single supreme being who created the universe with a decentralized system of smaller gods below this supreme being. People of all classes believed in witchcraft and magic. The Asante medical system was largely herbal similar to the Traditional African medicine of other pre-colonial African societies.

Society

editThomas Edward, in 1817, identified two classes in the empire. He referred to the upper class as "higher orders". The upper class were referred to as sikapo by the locals. Some owned large estates and thousands of slaves. "They were courteous, well-mannered, dignified and proud of their honor to such an extent a social disgrace, including something unintended as public flatulence could drive a man to commit suicide."[3] Men and women of higher orders bathed every morning with soap and warm water. They cleared their teeth several times every day with a brushing stick. The lower orders, known as abiato, were said to be small in stature with a filthy appearance. They were also described as ungrateful, insolent and licentious.[4] Historian Edgerton describes the wealth of Asante in the mid 19th century where he states it was not uncommon for members who worked with the royal administration to possess over £100,000 in gold. He recounts that such upper class Asante possessed more wealth than most upper class British families in the mid 19th century.[5]

The Asante state was matrilineal with all Asante citizens tracing their lineage to a single ancestor in an unbroken female line. The typical Asante family was headed by an Abusua panyin as leader who was supported by a senior woman in the family called the obaa panyin. The obaa panyin was more concerned about the affairs of women and girls in the family.[6] A mother's brother was the legal guardian of her children. The father had fewer legal responsibilities for his children with the exception of ensuring their well-being and to pay for a suitable wife for his son. A husband had some legal rights over his wife, including the right to cut off; her nose for adultery, her lips for betraying a secret or her ears for listening to private conversation. Women had relative equality such as the right to initiate divorce.[7] Menstruation was detested in Asante society. Women were secluded in huts during menses.[8]

Clothing

editEdgerton comments that prominent people in the empire often wore silk as commoners wore cotton whiles slaves dressed in black cloth. Garments indicated the wearer's rank, and their color denoted various meanings. Lighter colors as stated by Edgerton, could express innocence or rejoicing. White for example, was worn by Chiefs after making a sacrifice or by ordinary people after winning a court case. Dark colors were worn for funerals or mourning. Most clothes bore intricate designs that carried out various meanings.[9]

Some women wore Kente cloth dresses made by stitching together numerous handwoven strips of cotton or silk. There were laws that restricted certain Kente designs to various great men and women as exclusive symbols of their mobility and prestige. Some cotton or silk patterns on the Kente were designed solely for the Asantehene or king and could only be worn with his permission. The king and the wealthy wore elegant sandals decorated with gold but Edgerton writes that commoners went barefoot except during the rainy season when they wore wooden clogs to keep their feet out of the mud.[9] The Densinkran was a form of hairstyle introduced in the Asante Empire to mourn the Asante soldiers who perished at the Katamanso War. The hairstyle was later worn by women of royal descent and the elderly. It was also worn during funerals.[citation needed]

Cuisine

editPlants cultivated by the Asante include plantains, yams, manioc, corn, sweet potatoes, millet, beans, onions, peanuts, tomatoes, and many fruits.[10][11] Fufu was an important dish in the empire.[12] Women collected snails which formed a major part of Asante cuisine.[13] Cultural exchange with the Europeans at the coast introduced foreign dishes in Asante. The Asantehene or king of Asante enjoyed as part of his breakfast, European biscuits and tea.[14] Maize could be used to prepare porridge or loaf. Fritz Ramseyer accounts for the consumption of maize diet by the Asante army in 1869.[15] Kenkey was documented in the early 19th century by the William Hutton and the emissaries of Joseph Dupuis.[16] Cassava could be used to prepare Kokonte and rice was imported further south in modern Ghana. Rice was the main meal taken by the Asantehene and his officials at 2pm.[17] Scholar Miller writes on the lower consumption of meat by Asante people outside of the royal court. She cites William Hutton in 1820 who observed the presence of poultry, sheep and hogs of which the Asante lower class preferred to sell as they could not afford such diet.[17]

Games

editThe Oware is an abstract strategy game widely believed to be of Asante origin.[18] People sat under the shade provided by huge trees along the street where they played the board game.[8]

Chess was also played, where the King would have the move of a bishop, or a move similar to the bishops diagonal move. They also played Drafts (which is likely where the Dame Dame Adinkra symbol came from) similar to the Polish style[19]

Also, according to Bowdich:

"They have another game, for which a board is perforated like a cribbage board, but in numerous oblique lines, traversing each other in all directions, and each composed of three holes for pegs ; the players begin at the same instant, with an equal number of pegs, and he who inserts or completes a line first, in spite of the baulks of his adversary, takes a peg from him, until the stock of either is exhausted"[19]

It is unclear what specific game this was, apart from guessing it is a variant of cribbage

Slavery

editSlaves were typically taken as captives from enemies in warfare. The welfare of Asante slaves varied from being able to acquire wealth and intermarry with the master's family to being sacrificed in funeral ceremonies. The Asante sacrificed slaves upon the death of their masters. The Asante believed that slaves would follow their masters into the afterlife. Slaves could sometimes own other slaves, and could also request a new master for severe mistreatment.[20][21][22]

The modern-day Asante claim that slaves were seldom abused,[23] and that a person who abused a slave was held in high contempt by society.[24] In addition to slaves, there were pawns; these were individuals of free status sold into servitude as a means of paying a debt.[25] Asantehene Kwaku Dua I banned this practice of pawnship around 1838.[26]

Art

editArchitecture

editThe Asante traditional buildings are the only surviving buildings of Asante architecture. The construction and design of most Asante houses consisted of a timber framework filled up with clay which were thatched with sheaves of leaves. The surviving designated sites are shrines, but there have been many other buildings in the past with the same architectural style.[27] These buildings served as palaces and shrines as well as houses for the affluent.[28] The Asante Empire also built mausoleums which housed the tombs of several Asante leaders.

Generally, houses whether designed for human habitation or for the deities, consisted of four separate rectangular single-room buildings set around an open courtyard; the inner corners of adjacent buildings were linked by means of splayed screen walls, whose sides and angles could be adapted to allow for any inaccuracy in the initial layout. Typically, three of the buildings were completely open to the courtyard, while the fourth was partially enclosed, either by the door and windows, or by open-work screens flanking an opening.[29] The walls of temples and that of important buildings were designed with reliefs and sculptures.[30] Incised patterns, low reliefs and perforated fretwork are listed among the types of reliefs employed in Asante architecture by Livingstone.[30]

Bowdich gave a description for the construction process for the large town houses of Kumasi in the early 19th century.[31]

In building a house a mould was made for receiving the swish or clay by two rows of stakes and wattlework placed at a distance equal to the intended thickness of the wall; as two mud wall were raised at convenient distances, to receive the plum pudding stone which formed the walls of the vitrified fortresses in Scotland. The interval was then filled up with a gravelly clay, mixed with water, with which the outward surface of the frame or stake work was also thickly plastered, so as to impose the appearance of an entire thick mud wall. The houses had all gable ends, and three thick poles were joined to each; one from the highest point, forming the ridge of the roof, and one on each side, from the base of the triangular part of the gable; these supported a frame work of bamboo, over which an interwoven thatch of palm leaves was laid, and tied with the runners of trees, first to the large poles running from gable to gable, and afterwards, (within,) to the interlacing of the bamboo frame work, which was painted black and polished, so as to look much better than any rude ceiling would, of which they have no idea...The pillars, which assist to support the roof, and form the proscenium or open front, (which none but captains are allowed to have to their houses) [and] were thick poles, afterwards squared with a plastering of swish. The steps and raised floor of these rooms were clay and stone, with a thick layer of red earth, which abounds in the neighbourhood, and these were washed and painted daily, With an infusion of the same earth in water; it has all the appearance of red ochre, and from the abundance of iron ore in the neighbourhood, I do not doubt it... A white wash, very frequently renewed, was made from a clay in the neighbourhood...The doors were an entire piece of cotton wood, cut with great labour out of the stems or buttresses of that tree...Where they raised a first floor, the under room was divided into two by an intersecting wall, to support the rafters for the upper room, which were generally covered with a frame work thickly plastered over with red ochre....

— Bowdich.[31]

Dampan

editIn Kumasi, adampan[a] were loggias opened on to the streets of the city. Such structures were unoccupied, and inhabited rooms were built behind them.[32] Behind the dampan, 30–40 rooms could be hosted within an open yard with about 50–250 occupants.[32][34] These rooms were invisible from the main streets and they could be accessed through a small door beside the dampan. In the mid-19th century, William Winniett referred to the dampan as public rooms. Bowdich in the early 19th century, wrote that this feature was limited to the captains. In 1824, Dupuis described the dampans as "designed for the dispatch of public business." Wilks adds that the dampan were offices or bureau for officials.[32] McCasakie criticizes Wilk's take on the dampan as a gloss of the Asante architectural feature. He argues the dampan was an unstructured forum to raise household matters in public, to exchange information or to promote social interaction.[33]

Sumpene

editThese were elevated mounds built out of sun-baked clay that served as a platform for the Asantehene to sit and preside over public rituals in Kumasi.[35] The earliest description of the sumpene comes from Bowdich's journal in 1819 where he observed circular elevations of two steps, "the lower about 20 feet in circumference, like the bases of the old market crosses in England." These were raised in the middle of several streets and the King's chair was placed on this platform to sit. From which he would drink plam wine with his attendance encircling him. Freeman also observed that the sumpene were polished with red ochre and they stood between 6—8 feet tall and around 10 feet in diameter at the apex. He adds that "they are ascended by pyramidal ledges, or steps running all around and rising above one another, about a foot in depth, and 18 inches in width. Around these ledges the officers of the Household, with attendant domestics take their seats and thus a group is formed of from fifty to a hundred persons all distinctively seen."[36]

The palace complex

editThe palace complex was located in the eastern quarter of the central city and it covered some 5 acres.[37] The complex was secluded by a high wall, first described by Bowdich in the early 19th century.[37][38][39] Certain palace courtyards could contain up to 300 people.[39] Bowdich mentioned the "King's garden" as a part of the palace complex in 1817, which was "an area equal to one of the large squares in London."[39][40] Included in this garden were 4 large parasols and a dinner table which were used for state banquets.[39] A passage way lined with offices and living rooms of the officials served as the access point to the palace. It was referred to as a piazza by Bowdich and he estimated its length to be 200 yards long. He also added that it "lines the interior of the wall secluding the palace from the street."[37]

The Aban Palace was the palace of the Asantehene until its destruction during the Anglo-Ashanti War. The Aban was constructed with stone and it was completed by Asantehene Osei Bonsu in 1822.[41] The Aban was situated on the northern side of the palace complex.[37] According to Curnow, The building consisted of a tower, paved inner courtyard, window shutters and decorative balustrades.[42] One part of the Aban housed the wine store while most served the purpose of displaying the Asantehene's collection of arts and crafts. Christian Missionary, Freeman, reported of his visit to the Aban in 1841 where he noted several articles of manufactured glass on display in various rooms. These articles included candle-shades, glass tumblers and wine glasses.[43] According to Winwood Reade in 1874, “The rooms upstairs remind me of Wardour Street. Each was a perfect Old Curiosity Shop. Books in many languages, Bohemian glass, clocks, silver plate, old furniture, Persian rugs, Kidderminster carpets, pictures and engravings, numberless chests and coffers... With these were many specimens of Moorish and Ashanti handicraft...”[43]

Goldweights

editGold was an fundamental part of Asante art. The Asante just like all Akan kingdoms, used goldweights called abramo to measure gold dust.[44] Most goldweights are miniature representations of West African cultural items such as the adinkra symbols, plants, animals and people.[45] The earliest weights have been dated from 1400–1700 AD.[46] The weights were carved and cast through the lost wax technique.

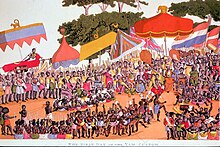

Festivals

editThe chiefs were responsible for directing the Adae, a religious ceremony approximately every 3 weeks during which the ancestors were praised and celebrated. During the Adae, the community drank palm wine and danced to the rhythm of dozens of drums.[9] The Adae Kese ceremony was another important event in Asante. The custom of holding this festival came into prominence between 1697 and 1699 when statehood was achieved for the people of Ashante after the war of independence, at the Battle of Feyiase, against the Denkyira.[47] It was a time to consecrate the remains of dead kings kept in a mausoleum at Bantama. Rituals included mass human and animal sacrifices.

The Annual Yam Festival celebrated between September and December, reinforced bonds of loyalty and patriotism to Asante. It dramatized the power of the state. When yams were ready for harvest, all district chiefs including chiefs of tributary districts as well as military leaders, were required to attend the festival with their retainers. The festival provided the platform for rewarding and punishing citizens of the state. Crimes committed by notables were intentionally withheld until the festival, where they faced trial and execution to serve as an object of lesson to all. Notables who had been loyal would be presented with honors and valuable gifts by the king.[48]

Religion

editOnyame was acknowledged to have created the visible world. In the 18th and 19th century, Onyame had neither priestly servitude nor temples devoted to his worship. Asante houses included Nyame dua that served as shrines for seeking solace or quietus in addressing Onyame. Onyame was the final arbiter of Justice and assigned every person his or her destiny and fate on Earth.[49]

The abosom or smaller gods were recognized as children of Onyame. The abosom were divided into three groups; the atano (gods from water bodies such as rivers), ewim (sky gods) and the abo (gods from the forests). The ewim were considered to be judgemental and merciless whiles the abo were sources of healing and medicine.[50] In Asante philosophy, the abosom could neither be manufactured or bought and were distinct from objects of worship such as charms, amulets and talismans, which were categorized as asuman in the Asante religion.[51] The Akomfo or fetish priests served as the medium between the abosom and the people.

Ancestor veneration formed a major characteristic of Asante religion. The Asante believed that every person had an immortal soul called Kra. When death occurred, the soul was believed to leave the physical body and inhabit the land of spirits where he or she would live a life similar on Earth. It was for this reason slaves were sacrificed in order to serve their Masters in the underworld. At times, widows also demanded to be sacrificed after the death of their husband. These ancestors were believed to reward people who adhered to Asante values and to punish offenders.[52] Through trade and wars of conquest, a number of Muslims from Northern Ghana formed part of Asante's bureaucracy. They prayed for the Asantehene and acted as medical consultants. In the 1840s, Kwaku Dua I, appointed Uthman Kamaghatay of Gbuipe in Gonja as Asante Adimen (The Imam of Asante). Despite a handful of Muslims in Asante society, Islam did not penetrate and form a major religion in the Empire.[53]

Folktale

editStories of Anansi became a prominent and familiar part of Asante oral culture. Tales of Anansi were encompassed into many kinds of fables.[54] Anansi was viewed synonymous with skill and wisdom in speech. The Sasabonsam was a creature in Asante mythology that was believed to hate humans. Without supervision from the abosom or gods, the sasabonsam was believed to encourage and foster witchcraft in Asante society. The sasabonsam had the appearance of the torso of a tall ape, the head and teeth of a carnivore, the underside of a snake and sometimes, the wings of a bat. It was covered in long, coarse red hair. The creature was believed to hook its feet onto trees where it hid from plain sight in order to trap and devour unsuspecting humans.[55]

Medicine

editThe Asante medicine was mainly herbal as diseases were tackled through medicinal plants. They tied their spiritual beliefs with the cause of diseases. According to Fynn, the common diseases among the Asante in the early 19th century were discovered to be lues, yaws, itches, scald heads, gonorrhea and pains in the bowels. It was testified by Dr. Teddlie who was an assistant surgeon of the Bowdich Mission on visit to Kumasi in 1817, that herbalists in Asante were treating all kinds of diseases and illness with green leaves, roots and barks of a lot of trees.[56] He observed that juices from plants were applied to cuts and bruises to stop bleeding.[57] According to scholars such as Seth Gadzepko, the Asante herbalists failed to promote the importance of hygiene, diet and nutrition in the Asante society. The poor and children who lived in an unsanitary environment were affected the most as a result.[56]

The Asante took some preventive measures against diseases. They valued sanitation and cleanliness. Rubbish of each house was burned every morning at the back of the street. Cleaning the streets and suburbs of Kumasi and the maintenance of sanitation was enforced by a bureaucratized Public Works Department. The workers of this department cleaned the streets daily and ensured that civilians had their compounds clean and weeded.[58] They did not wear uniforms but they carried canes to signify their position. In urban Asante, all physicians were organized and specialized under the Nsumankwaafiesu which was described by Asantehene Prempeh I as "the pharmacology where we had well trained and qualified physicians in charge whose duty was to attend to the sick and injured." The head of this office was the Nsumankwahene who served as the native doctor of the state and doctor of the Asantehene. There is evidence from the 19th century that the Asante practiced bone-setting. A fracture of an arm or leg was bound with splints.[58] Various surgical practices were familiar in the empire. Muslim doctors in Asante practiced bleeding, lancing and cupping. Variolation has been recorded to be practiced by 1817. Variolation itself was common in the Gold Coast by the 18th century. There were check points at Asante borders that prevented people from progressing to Asante if they exhibited signs of smallpox. Those who discovered signs of smallpox after crossing the borders were prevented from entering Kumasi and quarantined in remote villages.[58]

Dr. Teddlie noted that abortions of 3 months old were carried out with two plants known as the ahumba (a species of Ficus[59]) tree, and the awhintiwhinti plant in the native Asante language. These plants were powdered with pepper and the end product was boiled in fish soup.[57][59] The inner back of the wawa tree was used to cure colid and other stomach pains.[57] The bark of the oscisseree tree was used to stop dysentery and diarrhoea.[57][59] The Asante herbalists were also able to correct stomach acidity in pregnant women, heartburn and other related discomforts.[57] Tedlie recorded that a species of Urtica bruised and mixed with chalk was used for making such medicine.[59] Asante doctors believed that anyone suffering five wounds was defiled and an endanger to others. For this reason, such persons were sacrificed.[60] Asante doctors made an unsuccessful attempt to extract a bullet from the bullet wound of a British prisoner of war in the 19th century by squeezing it out of the wounded thigh with ligatures tied around the leg; one above and one below.[61] The Asante also made use of medicine on the battlefield. By the early 19th century, a full time medical corps was established as a branch of the Asante army.[62]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Obeng, J. Pashington (1996). Asante Catholicism: Religious and Cultural Reproduction Among the Akan of Ghana. Brill. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-04-10631-4.

An empire of a hundred thousand square miles, occupied by about three million people from different ethnic groups, made it imperative for the Asante to evolve sophisticated statal and parastatal institutions [...]

- ^ "Asante Empire". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-02-22.

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 23

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 24

- ^ Edgerton Robert B. (2010). Sick Societies. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451602326.

- ^ Seth K. Gadzekpo (2005), p. 75

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 40

- ^ a b Edgerton (2010), p. 41

- ^ a b c Edgerton (2010), pp. 41–42

- ^ Basil, Davidson African Civilization Revisited, Africa World Press: 1991, page 240. ISBN 9780865431232

- ^ Collins, Robert O.; Burns, James M. (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 9780521867467.

- ^ Miller (2022), p. 111

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 42

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), p. 34

- ^ Miller (2022), pp. 111–112

- ^ Miller (2022), p. 112

- ^ a b Miller (2022), pp. 114–115

- ^ "African Games of Strategy: A Teaching Manual". African Studies Program, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 20 December 1982. Retrieved 2017-12-20 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Bowdich, T. Edward (Thomas Edward) (1819). Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, with a statistical account of that kingdom, and geographical notices of other parts of the interior of Africa. University of Pittsburgh Library System. London, J. Murray.

- ^ Slavery in the Asante Empire of West Africa, Mises Institute

- ^ Alfred Burdon Ellis, , The Tshi-speaking peoples of the Gold Coast of West Africa Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, 1887. p. 290

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 1, 1997. p. 53.

- ^ Johann Gottlieb Christaller, Ashanti Proverbs: (the primitive ethics of a savage people), 1916, pp. 119–20.

- ^ History of the Ashanti Empire. Archived 2012-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 25

- ^ Austin, Gareth (2005). Labour, Land, and Capital in Ghana: From Slavery to Free Labour in Asante, 1807–1956. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- ^ "Asante Traditional Buildings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ Asante, Eric Appau; Kquofi, Steve; Larbi, Stephen (January 2015). "The symbolic significance of motifs on selected Asante religious temples". Journal of Aesthetics & Culture. 7 (1): 27006. doi:10.3402/jac.v7.27006. ISSN 2000-4214.

- ^ "Ghana Museums & Monuments Board". www.ghanamuseums.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ a b Livingston, Thomas W. (1974). "Ashanti and Dahomean Architectural Bas-Reliefs". African Studies Review. 17 (2): 435–448. doi:10.2307/523643. JSTOR 523643. S2CID 144030511.

- ^ a b Farrar, V Tarikhu (2020). Precolonial African Material Culture: Combatting Stereotypes of Technological Backwardness. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 228–229. ISBN 9781793606433.

- ^ a b c d Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 381

- ^ a b T.C. McCaskie (2003), p. 15–16

- ^ Blanton, Richard; Fargher, Lane (2007). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 310. ISBN 9780387738772.

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), p. 312

- ^ Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 384

- ^ a b c d Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 376–377

- ^ Joseline Donkoh, Wilhelmina (2004). "Kumasi: Ambience of Urbanity and Modernity". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana (8): 167–183 (169). ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41406712. S2CID 161253857.

- ^ a b c d Curnow, Kathy (30 September 2017). "Adum Royal Palace". The Bright Continent. Archived from the original on 2021-07-16. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Miller (2022), p. 126

- ^ Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 200

- ^ Curnow, Kathy (4 October 2017). "Palace, Fort, and Museum. Instruments of Power and Status: Construction and Destruction". The Bright Continent. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ a b Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 201

- ^ Bertolot, Alexander Ives (October 2003). "Good in Asante Courtly Arts". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2005-02-05. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Wilks,Ivor (1997). "Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries". In Bakewell, Peter (ed.). Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 7. ISBN 0860785130.

- ^ Garrard, T. F. 1972 "Studies in Akan Goldweights" (1), in Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 13(1): 1-20.

- ^ WhiteOrange. "Adae Kese Festival". Ghana Tourism Authourity. Archived from the original on 2019-12-26. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 28

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), p. 107

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), pp. 108–109

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), pp. 110–111

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 36

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), pp. 135–136

- ^ Zobel Marshall, Emily (2012) Anansi's Journey: A Story of Jamaican Cultural Resistance. University of the West Indies Press: Kingston, Jamaica. ISBN 978-9766402617

- ^ T.C. McCaskie (2003), pp. 118–119

- ^ a b Seth K. Gadzekpo (2005), p. 67

- ^ a b c d e Prince A. Kuffour (2015). Concise Notes on African and Ghanaian History. K4 Series Investment Ventures. pp. 231–232. ISBN 9789988159306. Retrieved 2020-12-16 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ a b c Maier, D. (1979). "Nineteenth-Century Asante Medical Practices". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 21 (1): 63–81. doi:10.1017/S0010417500012652. JSTOR 178452. PMID 11614369. S2CID 19587869.

- ^ a b c d McCaskie, Tom C. (2017). ""The Art or Mystery of Physick" – Asante Medicinal Plants and the Western Ordering of Botanical Knowledge". History in Africa. 44: 27–62. doi:10.1017/hia.2016.11. JSTOR 26362152. S2CID 163335275.

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 80

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 79

- ^ Edgerton (2010), p. 53

Bibliography

edit- Edgerton, Robert B. (2010). The Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred-Year War For Africa's Gold Coast. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451603736.

- Ivor Wilks (1989). Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521379946. Retrieved 2020-12-29 – via Books.google.com.

- Seth K. Gadzekpo (2005). History of Ghana: Since Pre-history. Excellent Pub. and Print. ISBN 9988070810. Retrieved 2020-12-27 – via Books.google.com.

- T.C. McCaskie (2003). State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521894326.

- Miller, Brandi Simpson (2022). Food and Identity in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Ghana: Food, Fights, and Regionalism. Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030884031.