A cordon sanitaire (French pronunciation: [kɔʁdɔ̃ sanitɛʁ], French for "sanitary cordon") is the restriction of movement of people into or out of a defined geographic area, such as a community, region, or country.[1] The term originally denoted a barrier used to stop the spread of infectious diseases. The term is also often used metaphorically, in English, to refer to attempts to prevent the spread of an ideology deemed unwanted or dangerous,[2] such as the containment policy adopted by George F. Kennan against the Soviet Union (see cordon sanitaire in politics).

Origin

editThe term cordon sanitaire dates to 1821, when the Duke de Richelieu deployed French troops to the border between France and Spain, to prevent yellow fever from spreading into France.[3][4]

Definition

editA cordon sanitaire is generally created around an area experiencing an epidemic or an outbreak of infectious disease, or along the border between two nations. Once the cordon is established, people from the affected area are no longer allowed to leave or enter it. In the most extreme form, the cordon is not lifted until the infection is extinguished.[5] Traditionally, the line around a cordon sanitaire was quite physical; a fence or wall was built, armed troops patrolled, and inside, inhabitants were left to battle the affliction without help. In some cases, a "reverse cordon sanitaire" (also known as protective sequestration) may be imposed on healthy communities that are attempting to keep an infection from being introduced. Public health specialists have included cordon sanitaire along with quarantine and medical isolation as "nonpharmaceutical interventions" designed to prevent the transmission of microbial pathogens through social distancing.[6]

The cordon sanitaire is not used now in its most extreme historical form, mainly due to our improved understanding of disease transmission, treatment and prevention. Today its function is primarily to facilitate the identification of infectious disease and to prevent its transmission. In its more traditional role, the cordon also remains a useful intervention under conditions in which: 1) the infection is highly virulent (contagious and likely to cause illness); 2) the case fatality rate is very high; 3) treatment is nonexistent or difficult; and 4) there is no vaccine, or other means of immunizing large numbers of people (such as needles or syringes) are lacking.[7] During the COVID-19 pandemic cordons sanitaires were imposed on geographic regions around the world in an attempt to contain the infection.[8]

16th century

edit- In 1523, during a plague outbreak in Birgu, the town was cordoned off by guards to prevent the disease from spreading to the rest of Malta.[9]

17th century

edit- In 1655, cordon sanitaire was imposed on the town of Żabbar in Malta after a plague outbreak was detected. The disease spread to other settlements and similar restrictive measures were imposed, and the outbreak was successfully contained after causing 20 deaths.[10]

- In May 1666, the English village of Eyam famously imposed a cordon sanitaire on itself after an outbreak of the bubonic plague in the community. During the next 14 months almost eighty percent of the inhabitants died.[11] A perimeter of stones was laid out surrounding the village and no one passed the boundary in either direction until November 1667, when the pestilence had run its course. Neighbouring communities provided food for Eyam, leaving supplies in designated locations along the boundary cordon and receiving payment in coins "disinfected" by running water or vinegar.[12]: 72

18th century

edit- During the Great Northern War plague outbreak of 1708–1712, cordons sanitaires were established around affected towns like Stralsund, Helsingør, and Königsberg; one was also established around the whole Duchy of Prussia and another one between Scania and the Danish isles along the Sound, with Saltholm as the central quarantine station.[13]

- In 1770 the Empress Maria Theresa set up a cordon sanitaire between Austria and the Ottoman Empire to prevent people and goods infected with plague from crossing the border. Cotton and wool were held in storehouses for weeks, with peasants paid to sleep on the bales and monitored to see if they showed signs of disease. Travelers were quarantined for 21 days under ordinary circumstances and up to 48 days when there was confirmation of plague being active in Ottoman territory. The cordon was maintained until 1871, and there were no major outbreaks of plague in Austrian territory after the cordon sanitaire was established, whereas the Ottoman Empire continued to suffer frequent epidemics of plague until the mid-19th century.[14]

- During the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic, roads and bridges leading to the city were blocked off by soldiers from the local militia to prevent the illness from spreading. This was before the transmission mechanics of yellow fever were well understood.[15][page needed][16]

19th century

edit- During the 1813–1814 Malta plague epidemic, the main urban settlements of Malta (Valletta, Floriana and the Three Cities) and rural settlements with a high mortality rate (Birkirkara, Qormi, Żebbuġ and later Xagħra) were cordoned off by the military to prevent people from entering or leaving.[17]

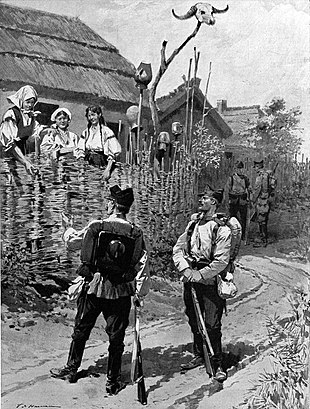

- The first actual use of the term cordon sanitaire was in 1821, when the Duke de Richelieu deployed 30,000 French troops to the border between France and Spain in the Pyrenees Mountains, allegedly in order to prevent yellow fever from spreading from Barcelona into France[3] but in fact mainly to prevent the spread of liberal ideas from constitutional Spain.[4]

- The 1821 yellow fever epidemic ravaged Barcelona and a cordon sanitaire was set up around the entire city of 150,000 people. Between 18,000 and 20,000 died in four months.[14]

- During the 1830 cholera outbreak in Russia, Moscow was surrounded by a military cordon, most roads leading to the city were dug up to hinder travel, and all but four entrances to the city were sealed.[14]

- During the 1856 yellow fever epidemic a cordon sanitaire was implemented in several cities in the state of Georgia with moderate success.[18]

- In 1869, Adrien Proust (father of novelist Marcel Proust) proposed the use of an international cordon sanitaire to control the spread of cholera, which had emerged from India and was threatening Europe and Africa. Proust proposed that all ships bound for Europe from India and Southeast Asia be quarantined at Suez, however his ideas were not generally embraced.[19][20]

- In 1882, in response to a virulent outbreak of yellow fever in Brownsville, Texas, and in northern Mexico, a cordon sanitaire was established 180 miles north of the city, terminating at the Rio Grande to the west and the Gulf of Mexico to the east. People traveling north had to remain quarantined at the cordon for 10 days before they were certified disease-free and could proceed.[14]

- In 1888, during a yellow fever epidemic, the city of Jacksonville, Florida, was surrounded by an armed cordon sanitaire by order of Governor Edward A. Perry.[21]

- In 1899, an outbreak of the plague in Honolulu was managed by a cordon sanitaire around the Chinatown district. In an attempt to control the infection, a barbed wire perimeter was created and people's belongings and homes were burned.[22]

20th century

edit- During the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904 San Francisco's Chinatown was subjected to a cordon sanitaire.[23]

- In 1902, Louisiana imposed a cordon sanitaire to prevent Italian immigrants from disembarking at the port of New Orleans. The shipping company sued for damages, but the state's right to impose a cordon was upheld in Compagnie Francaise de Navigation a Vapeur v. Louisiana Board of Health.

- From 1903 to 1914, the Belgian colonial government imposed a cordon sanitaire on Uele Province in the Belgian Congo to control outbreaks of trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness).[24]

- 1918 flu pandemic:

- The 1918 flu spread so rapidly that, in general, there was no time to implement cordons sanitaires. However, to prevent an introduction of the infection, residents of Gunnison, Colorado isolated themselves from the surrounding area for two months at the end of 1918. All highways were barricaded near the county lines. Train conductors warned all passengers that if they stepped outside of the train in Gunnison, they would be arrested and quarantined for five days. As a result of this protective sequestration, no one died of influenza in Gunnison during the epidemic.[25]

- During the 1918 flu pandemic, the then Governor of American Samoa, John Martin Poyer, imposed a reverse cordon sanitaire of the islands from all incoming ships, successfully achieving zero deaths within the territory.[26] In contrast, the neighboring New Zealand-controlled Western Samoa was among the hardest hit, with a 90% infection rate and over 20% of its adults dying from the disease.[27]

- In late 1918, Spain attempted unsuccessfully to prevent the spread of the 1918 flu by imposing border controls, roadblocks, restricted rail travel, and a maritime cordon sanitaire prohibiting ships with sick passengers from landing, but by then the epidemic was already in progress.[28][page needed]

- During the 1972 Yugoslav smallpox outbreak, over 10,000 people were sequestered in cordons sanitaires of villages and neighborhoods using roadblocks, and there was a general prohibition of public assembly, a closure of all borders and a prohibition of all non-essential travel.[29]: 17

- In 1995, a cordon sanitaire was used to control an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Kikwit, Zaire.[30][31][7] President Mobutu Sese Seko surrounded the town with troops and suspended all flights into the community. Inside Kikwit, the World Health Organization and Zaire medical teams erected further cordons sanitaires, isolating burial and treatment zones from the general population.[32][page needed]

21st century

edit- During the 2003 SARS outbreak in Canada, "community quarantine" was used to successfully reduce transmission of the disease.[33]

- During the 2003 SARS outbreak in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, large-scale quarantine was imposed on travelers arriving from other SARS areas, work and school contacts of suspected cases, and, in a few instances, entire apartment complexes where high attack rates of SARS were occurring.[34] In China, entire villages in rural areas were quarantined and no travel was allowed in or out of the villages. One village in Hebei province was quarantined from 12 April 2003 until 13 May. Tens of thousands of individuals fled from areas when they learned of an impending cordon sanitaire, thereby possibly spreading the epidemic.[35]

- In August 2014, a cordon sanitaire was established around some of the most affected areas of the Western African Ebola virus epidemic.[36][5] On 19 August 2014, the Liberian government quarantined the entirety of the district of West Point of the capital, Monrovia, and issued a statewide curfew.[37][38] The cordon sanitaire of the West Point area was lifted on 30 August. The information minister, Lewis Brown, said that this step was taken to ease efforts to screen, test, and treat residents.[39]

- In January 2020, a cordon sanitaire was drawn around the Chinese city of Wuhan, known as the Wuhan lockdown, due to what became the COVID-19 pandemic.[40] As the outbreak expanded, travel restrictions impacted over half of the Chinese population, creating what may be the largest cordon sanitaire in history[41] until this was surpassed by the lockdown in India, affecting the entire 1.3 billion population, in March 2020.[42] By April 2020, half of the world's population was under some form of lockdown in more than 90 countries[43] in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the 2020–2021 Malaysian movement control order[44] and a nationwide lockdown in Italy.[45]

Ethical considerations

editGuidance on when and how human rights can be restricted to prevent the spread of infectious disease is found in the Siracusa Principles, a non-binding document developed by the Siracusa International Institute for Criminal Justice and Human Rights and adopted by the United Nations Economic and Social Council in 1984.[46] The Siracusa Principles state that restrictions on human rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights must meet standards of legality, evidence-based necessity, proportionality, and gradualism, noting that public health can be used as grounds for limiting certain rights if the state needs to take measures "aimed at preventing disease or injury or providing care for the sick and injured." Limitations on rights (such as a cordon sanitaire) must be "strictly necessary," meaning that they must:

- respond to a pressing public or social need (health)

- proportionately pursue a legitimate aim (prevent the spread of infectious disease)

- be the least restrictive means required for achieving the purpose of the limitation

- be provided for and carried out in accordance with the law

- be neither arbitrary nor discriminatory

- only limit rights that are within the jurisdiction of the state seeking to impose the limitation.[47]

In addition, when a cordon sanitaire is imposed, public health ethics specify that:

- all restrictive actions must be well-supported by data and scientific evidence

- all information must be made available to the public

- all actions must be explained clearly to those whose rights are restricted and to the public

- all actions must be subject to regular review and reconsideration.

Finally, the state is ethically obligated to guarantee that:

- infected people will not be threatened or abused

- basic needs such as food, water, medical care, and preventive care will be provided

- communication with loved ones and with caretakers will be permitted

- constraints on freedom will be applied equally, regardless of social considerations

- those who are affected will be compensated fairly for economic and material losses, including salary.[48]

In popular culture

edit- A cordon sanitaire was used as a plot device by Albert Camus in his 1947 novel The Plague.

- In the 1995 film Outbreak, an Ebola-like virus brought from Africa causes an epidemic in a small town in California, resulting in the United States Army forming a cordon sanitaire around the town.

- The 2002 film 28 Days Later depicts a cordon sanitaire imposed on Great Britain as a viral infection devastates the population.

- In The Last Town on Earth, a 2006 novel by Thomas Mullen, the town of Commonwealth, Washington in 1918 imposes a reverse cordon sanitaire to avoid the Spanish flu, however the disease is introduced by a wandering soldier.

- In the 2006 novel World War Z the nation of Israel imposes a reverse cordon sanitaire to keep zombies out.

- In the 2011 film Contagion, the city of Chicago is cordoned off to contain the spread of a meningoencephalitis virus.

- In the 2014 Belgian TV series Cordon, a cordon sanitaire is set up to contain an outbreak of avian influenza in Antwerp.

- In the 2016 television limited series Containment a cordon sanitaire is set up to contain an infectious virus in Atlanta, Georgia.

- In the 2019 novel The Dreamers by Karen Thompson Walker, the fictional California town of Santa Lora is placed under cordon sanitaire due to a sleeping sickness that infects its residents.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rothstein, Mark A. (2015). "From SARS to Ebola: Legal and Ethical Considerations for Modern Quarantine" (PDF). Indiana Health Law Review. 12 (1): 227. doi:10.18060/18963. SSRN 2499701.

- ^ Fisher, Harold H. (1927). The Famine in Soviet Russia, 1919–1923. New York: Macmillan. p. 25.

- ^ a b Taylor, James (1882). The Age We Live In: A History of the Nineteenth Century. Oxford University. p. 222.

- ^ a b Nichols, Irby C. (1972). The European Pentarchy and the Congress of Verona, 1822. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-94-010-2725-0.

- ^ a b McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (12 August 2014). "Using a Tactic Unseen in a Century, Countries Cordon Off Ebola-Racked Areas". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Markel, Howard; Lipman, Harvey B.; Navarro, J. Alexander; Sloan, Alexandra; Michalsen, Joseph R.; Stern, Alexandra Minna; Cetron, Martin S. (8 August 2007). "Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities During the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic" (PDF). JAMA. 298 (6): 644–654. doi:10.1001/jama.298.6.644. PMID 17684187.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, Rachel Kaplan; Hoffmann, Keith (19 February 2015). "Ethical Considerations in the Use of Cordons Sanitaires". Clinical Correlations. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Baird, Robert P. (11 March 2020). "What It Means to Contain and Mitigate the Coronavirus". The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Savona-Ventura, Charles. The Medical History of the Maltese Islands: Medieval Medicine (PDF). University of Malta. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Savona-Ventura, Charles (2015) [2004]. Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta [1530–1798]. Self-published. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-1-326-48222-0.

- ^ Race, Philip (1995). "Some Further Consideration of the Plague in Eyam, 1665/6" (PDF). Local Population Studies. 54 (54): 56–65. PMID 11639747.

- ^ "The Boundary Stone". Stoney Middleton Heritage. 3 November 2014.

- ^ Frandsen, Karl-Erik (2010). The Last Plague in the Baltic Region, 1709–1713. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-635-0770-7.

- ^ a b c d Kohn, George C. (2007). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present (PDF). Infobase Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4381-2923-5.

- ^ Powell, J. H. (2014). Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793. Studies in Health, Illness, and Caregiving. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9117-9.

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob (30 January 2008). "A Short History of Yellow Fever in the US". Destroying Angel: Benjamin Rush, Yellow Fever and the Birth of Modern Medicine. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Mangion, Fabian (19 May 2013). "Maltese islands devastated by a deadly epidemic 200 years ago". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020.

- ^ Campbell, Henry Fraser (1879). "The Yellow Fever Quarantine of the Future, as Organized upon the Portability of Atmospheric Germs and upon the Non-Contagiousness of the Disease". Public Health Papers and Reports. 5: 131–144. PMC 2272165. PMID 19600008.

- ^ Carter, William C. (2002). Marcel Proust: A Life. Yale University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-300-09400-0.

- ^ Weissmann, Gerald (January 2015). "Ebola, Dynamin, and the Cordon Sanitaire of Dr. Adrien Proust". The FASEB Journal. 29 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1096/fj.15-0101ufm. PMID 25561464. S2CID 7062504.

- ^ "Epidemic Disease and the Establishment of the Board of Health". Pestilence, Potions, and Persistence: Early Florida Medicine. Florida Memory. p. 2. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (15 August 2014). "The Disastrous Cordon Sanitaire Used on Honolulu's Chinatown in 1900". Slate. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Skubik, Mark M. (May 2002). Public Health Politics and the San Francisco Plague Epidemic of 1900–1904 (PDF) (Thesis). San Jose State University. doi:10.31979/etd.hq5x-ph4v.

- ^ Lyons, Maryinez (January 1985). "From 'Death Camps' to Cordon Sanitaire: The Development of Sleeping Sickness Policy in the Uele District of the Belgian Congo, 1903–1914". The Journal of African History. 26 (1): 69–91. doi:10.1017/S0021853700023094. JSTOR 181839. PMID 11617235. S2CID 9787086.

- ^ "Gunnison". Center for the History of Medicine, University of Michigan. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Okin, Peter Oliver (January 2012). The Yellow Flag of Quarantine: An Analysis of the Historical and Prospective Impacts of Socio-Legal Controls Over Contagion (PhD). University of South Florida. p. 232. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Patterson, Michael Robert (21 December 2005). "John Martin Poyer, Commander, United States Navy". Arlington National Cemetery Website. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Davis, Ryan A. (2013). The Spanish Flu: Narrative and Cultural Identity in Spain, 1918. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-33921-8.

- ^ "Smallpox in Yugoslavia" (PDF). The Climate Change and Public Health Law Site. 22 September 1972. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Garrett, Laurie (14 August 2014). "Heartless but Effective: I've Seen 'Cordon Sanitaire' Work Against Ebola". The New Republic. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (19 May 1995). "Outbreak of Ebola Viral Hemorrhagic Fever – Zaire, 1995". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 44 (19): 381–382. PMID 7739512.

- ^ Garrett, Laurie (2011). Betrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-1-4013-0386-0.

- ^ Bondy, Susan J; Russell, Margaret L; Laflèche, Julie ML; Rea, Elizabeth (2009). "Quantifying the impact of community quarantine on SARS transmission in Ontario: estimation of secondary case count difference and number needed to quarantine". BMC Public Health. 9: 488. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-488. PMC 2808319. PMID 20034405.

- ^ Cetron, Martin; Maloney, Susan; Koppaka, Ram; Simone, Patricia (2004). "Isolation and Quarantine: Containment Strategies for SARS 2003". Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak. National Academies Press. pp. 71–83. doi:10.17226/10915. ISBN 0-309-59433-2. PMID 22553895.

- ^ Rothstein, Mark A.; Alcalde, M. Gabriela; Elster, Nanette R.; Majumder, Mary Anderlik; Palmer, Larry I.; Stone, T. Howard; Hoffman, Richard E. (November 2003). Quarantine and Isolation: Lessons learned from SARS (PDF) (Report). Institute for Bioethics, Health Policy and Law; University of Louisville School of Medicine. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Nyenswah, Tolbert; Blackley, David J.; Freeman, Tabeh; Lindblade, Kim A.; Arzoaquoi, Samson K.; Mott, Joshua A.; Williams, Justin N.; Halldin, Cara N.; Kollie, Francis; Laney, A. Scott (27 February 2015). "Community Quarantine to Interrupt Ebola Virus Transmission — Mawah Village, Bong County, Liberia, August–October, 2014". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 64 (7): 179–182. PMC 5779591. PMID 25719679.

- ^ "Liberian Soldiers Seal Slum to Halt Ebola". NBC News. 20 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ MacDougall, Clair; Giahyue, James Harding (20 August 2014). "Liberia police fire on protesters as West Africa's Ebola toll hits 1,350". Reuters. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ Paye-Layleh, Jonathan (30 August 2014). "Liberian Ebola survivor calls for quick production of experimental drug". Global News. Associated Press. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ Levenson, Michael (22 January 2020). "Scale of China's Wuhan Shutdown Is Believed to Be Without Precedent". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Rachman, Gideon (28 February 2020). "Coronavirus: how the outbreak is changing global politics". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Singh, Karan Deep; Goel, Vindu; Kumar, Hari; Gettleman, Jeffrey (25 March 2020). "India, Day 1: World's Largest Coronavirus Lockdown Begins". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Sandford, Alasdair (2 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Half of humanity now on lockdown as 90 countries call for confinement". Euronews. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Tang, Ashley (16 March 2020). "Malaysia announces movement control order after spike in Covid-19 cases (updated)". The Star. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Northern Italy quarantines 16 million people". BBC News. 8 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ United Nations Economic and Social Council UN Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, "The Siracusa Principles on the limitation and derogation provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights," Section I.A.12 UN Doc. E/CN.4/1985/4, Annex. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR; 1985. www.unhcr.org, accessed 5 February 2020

- ^ Todrys, K. W.; Howe, E.; Amon, J. J. (2013). "Failing Siracusa: Governments' obligations to find the least restrictive options for tuberculosis control". Public Health Action. 3 (1): 7–10. doi:10.5588/pha.12.0094. PMC 4463097. PMID 26392987.

- ^ M. Pabst Battin, Leslie P. Francis, Jay A. Jacobson, The Patient as Victim and Vector: Ethics and Infectious Disease, Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 019533583X