Megapnosaurus (meaning "big dead lizard", from Greek μέγα = "big", ἄπνοος = "not breathing", "dead", σαῦρος = "lizard"[1]) is an extinct genus of coelophysid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 188 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Africa. The species was a small to medium-sized, lightly built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, that could grow up to 2.2 m (7.2 ft) long and weigh up to 13 kg (29 lb).

| Megapnosaurus Temporal range: Early Jurassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Coelophysidae |

| Genus: | †Megapnosaurus Ivie et al., 2001 |

| Type species | |

| †Megapnosaurus rhodesiensis (Raath, 1969) Ivie et al., 2001

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It was originally given the genus name Syntarsus,[2] but that name was later determined to be preoccupied by a beetle.[1] The species was subsequently given a new genus name, Megapnosaurus, by Ivie, Ślipiński & Węgrzynowicz in 2001. Some studies have classified it as a species within the genus Coelophysis,[3] but this interpretation has been challenged by more subsequent studies and the genus Megapnosaurus is now considered valid.[4][5][6]

Discovery and history

editThe first fossils of Megapnosaurus were found in 1963 by a group of students from Northlea School on Southcote Farm in Nyamandhlovu, Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia). Michael A. Raath, the describer, was shown the fossils by school staff in 1964 and over several weeks, was excavated from the Forest Sandstone, the layers dating to the early Jurassic.[2] The type specimen (QG 1) consisted of a well preserved postcranial skeleton, missing only the skull and cervical vertebrae.[7][2] In another sandstone block, a few fossils of another specimen intermixed with the bones of a prosauropod, likely Massospondylus. Later in 1968, Raath and D. F. Lovemore discovered additional Jurassic rock layers northeast of the type locality of Southcote Farm.[7] These rock layers were then known as the Maura River Beds, but due to the strata bearing fossils of Massospondylus, the beds were determined to be the same age as those of the Forest Sandstone.[7] This second locality produced many articulated partial skeletons of Massospondylus, but only fragmentary postcranial remains of Megapnosaurus.[7] Raath would name the animal in 1969, dubbing it Syntarsus rhodesiensis, after the fused tarsal bones in its foot.[2]

Still in search of complete skeletons, Raath continued searching in the Jurassic rocks of Zimbabwe until finding what would become the most productive S. rhodesiensis-bearing locality near the Chitake River in 1972.[7] The quarry contained hundreds of bones of at least 26 individuals from many growth stages, making it one of the most productive quarries for African Theropods. The quarry contained several skulls and cervical vertebrae, elements missing in previously collected specimens, and some specimens even preserved gastralia, sexual dimorphism, and gut contents.[7] The fossils were described in detail by Raath in his thesis in 1977, including skeletal and musculoskeletal reconstructions of S. rhodesiensis. All specimens collected from Southcote, Maura River, and Chitake River now reside at the Queen Victoria Museum.[7]

Possible & reclassified Megapnosaurus remains

editIn 1989, a second species of "Syntarsus" was proposed as Syntarsus kayentakatae, a description by Timothy Rowe of a well preserved skull and partial remains of postcranial skeleton.[8] The fossils came from the early Jurassic strata of the Kayenta Formation in Arizona, USA. The phylogenetic position of "Syntarsus" kayentakatae is debated, with a position in Megapnosaurus,[9][8] Coelophysis,[10] or a making a new genus being proposed.[5][11]

The next year Darlington Munyikwa and Raath described a partial snout of "S." rhodesiensis from the Elliot Formation in South Africa,[12] but the material has been referred to Dracovenator.[13] A “Syntarsus” specimen was discovered in the United Kingdom in the 1950s and consisted of several postcranial elements. The specimen have now been referred to a new genus and species, Pendraig milnerae in 2021.[4] A partial coelophysoid sacrum and several additional elements from the Early Jurassic of Mexico were described as a new species of "Syntarsus", "Syntarsus" "mexicanum", in 2004.[14] The remains were not given proper description in their naming and are likely from an indeterminate coelophysoid.[15] Fragmentary coelophysid specimens (FMNH CUP 2089 and FMNH CUP 2090) from the Lufeng Formation of southern China have been identified as cf. Megapnosaurus, though phylogenetic analyses cannot be conducted due to poor preservation.[16][17]

Description

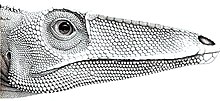

editMegapnosaurus rhodesiensis measured up to 2.2 m (7.2 ft) long from nose to tail and weighed up to 13 kg (29 lb).[18] It was a lean, elongated species of theropod dinosaur with an S-shaped neck, long hind limbs that resembled the legs of large birds such as the secretarybird, shorter forelimbs with four digits on each hand unlike most later theropods, and a long tail. While still lean, it sported a more robust frame than other members of Coelophysoidea. Its lithe and superifically bird-like body lead to M. rhodesiensis being one of the first dinosaurs to be portrayed with feathers, though there is no direct evidence that it actually had feathers.[19]

The bones of at least 30 M. rhodesiensis individuals were found together in a fossil bed in Zimbabwe, so paleontologists think it may have hunted in packs. The various fossils attributed to this species have been dated over a relatively large time span – the Hettangian, Sinemurian, and Pliensbachian stages of the Early Jurassic – meaning the fossils represent either a highly successful genus or a few closely related animals all currently assigned to Coelophysis.[20]

Specimen UCMP V128659 was discovered in 1982 and referred to Megapnosaurus kayentakatae by Rowe (1989),[21] as a subadult gracile individual and later, Tykoski (1998)[22] agreed. Gay (2010) described the specimen as the new tetanurine taxon Kayentavenator elysiae,[23] but Mortimer (2010) pointed out that there was no published evidence that Kayentavenator is the same taxon as M. kayentakatae.[24]

Classification

editThe cladogram below was recovered in a study by Ezcurra et al. (2021).[5]

| Coelophysoidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Syntarsus" rhodesiensis was first described by Raath (1969) and assigned to Podokesauridae.[2] The taxon "Podokesauridae", was abandoned since its type specimen was destroyed in a fire and can no longer be compared to new finds. Over the years paleontologists assigned this genus to Ceratosauridae (Welles, 1984), Procompsognathidae (Parrish and Carpenter, 1986) and Ceratosauria (Gauthier, 1986). Most recently, it has been assigned to Coelophysidae by Tykoski and Rowe (2004), Ezcurra and Novas (2007) and Ezcurra (2007), which is the current scientific consensus.[20][5][25]

According to Tykoski and Rowe (2004) Coelophysis rhodesiensis can be distinguished based on the following characteristics:[20] it differs from Coelophysis bauri in the pit at the base of the nasal process of the premaxilla; it differs from C.? kayentakatae because the promaxillary fenestra is absent and the nasal crests are absent; the frontal bones on the skull are not separated by a midline anterior extension of the parietal bones; the anterior astragalar surface is flat; metacarpal I has a reduced distal medial condyle (noted by Ezcurra, 2006); the anterior margin of antorbital fossa is blunt and squared (noted by Carrano et al., 2012); the base of lacrimal vertical ramus width is less than 30% its height (noted by Carrano et al., 2012); the maxillary and dentary tooth rows end posteriorly at the anterior rim of the lacrimal bone (noted by Carrano et al., 2012)

Marsh and Rowe (2020) retain the generic name Syntarsus for both QG 1 and MNA V2623, and the respective specimens assigned to these taxa, as opposed to Coelophysis or Megapnosaurus, due to systematic relationships within Coelophysoidea in flux. As such, congenericity or the need for Megapnosaurus would not be supported if Coelophysis bauri, Syntarsus rhodesiensis, and Syntarsus kayentakatae do not form respective clades, as evidenced by their phylogenetic analyses.[26]

Ezcurra et al. (2021) found Megapnosaurus rhodesiensis to have been quite distant from both Coelophysis bauri (currently the only undisputed species in genus Coelophysis) and "Syntarsus" kayentakatae (not currently classified in a valid genus). In this analysis, the closest relatives of M. rhodesiensis are Camposaurus, Segisaurus and Lucianovenator.[5] Similar results were found in analyses years before, supporting this position.[25][27]

Paleoecology

editProvenance and occurrence

editThe holotype of M. rhodesiensis (QG1) has been recovered in Upper Elliot Formation in South Africa, as well as the Chitake River bonebed quarry at the Forest Sandstone Formation in Rhodesia (now known as Zimbabwe). In South Africa, several individuals were collected in 1985 from mudstone deposited during the Hettangian stage of the Jurassic period, approximately 201 to 199 million years ago.[28] In Zimbabwe, twenty-six individuals were collected in 1963, 1968 and 1972 from yellow sandstone deposited during the Hettangian stage of the Jurassic period, approximately 201 to 199 million years ago.[2][29][30]

Fauna and habitat

editThe Upper Elliot Formation is thought to have been an ancient floodplain. Fossils of the prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus and Ignavusaurus have been recovered from the Upper Elliot Formation, which boasts the world's most diverse fauna of early Jurassic ornithischian dinosaurs, including Abrictosaurus, Fabrosaurus, Heterodontosaurus, and Lesothosaurus, among others. The Forest Sandstone Formation was the paleoenvironment of protosuchid crocodiles, sphenodonts, the dinosaur Massospondylus and indeterminate remains of a prosauropod. Paul (1988) argued that members of the species lived among desert dunes and oases and hunted juvenile and adult prosauropods.[31]

Paleobiology

editGrowth

editAge determination studies using growth ring counts suggest that the longevity of M. rhodesiensis was approximately seven years.[32] Recent research has found that M. rhodesiensis had highly variable growth between individuals, with some specimens being larger in their immature phase than smaller adults were when completely mature; this indicates that the supposed presence of distinct morphs is simply the result of individual variation. This highly variable growth was likely ancestral to dinosaurs but later lost, and may have given such early dinosaurs an evolutionary advantage in surviving harsh environmental challenges.[33]

Feeding and diet

editThe supposed "weak joint" in the jaw, led to the early hypothesis that dinosaurs such as these were scavengers, as the front teeth and bone structure of the jaw were thought to be too weak to take down and hold struggling prey. M. rhodesiensis was one of the first dinosaurs to be portrayed with feathers, though there is no direct evidence that it actually had feathers. Paul (1988) suggested that members of the species may have hunted in packs, preying upon "prosauropods" (basal sauropodomorphs) and early lizards.[31]

Comparisons between the scleral rings of M. rhodesiensis and modern birds and non-avian reptiles indicate that it may have been nocturnal.[34]

Paleopathology

editIn M. rhodesiensis, healed fractures of the tibia and metatarsus have been observed, but are very rare. "[T]he supporting butresses of the second sacral rib" in one specimen of Syntarsus rhodesiensis showed signs of fluctuating asymmetry. Fluctuating asymmetry results from developmental disturbances and is more common in populations under stress and can therefore be informative about the quality of conditions a dinosaur lived under.[35]

Ichnology

editDinosaur footprints that were later attributed to M. rhodesiensis were discovered in Rhodesia in 1915. These tracks were discovered at the Nyamandhlovu Sandstones Formation, in eolian red sandstone that was deposited in the Late Triassic, approximately 235 to 201 million years ago.[36]

References

edit- ^ a b Ivie, M.A.; Slipinski, S.A.; Wegrzynowicz, P. (2001). "Generic Homonyms in the Colydiinae (Coleoptera: Zopheridae)". Insecta Mundi. 15 (1): 184.

- ^ a b c d e f Raath, (1969). "A new Coelurosaurian dinosaur from the Forest Sandstone of Rhodesia." Arnoldia Rhodesia. 4 (28): 1-25.

- ^ Ezcurra, M. D.; Brusatte, S. L. (2011). "Taxonomic and phylogenetic reassessment of the early neotheropod dinosaur Camposaurus arizonensis from the Late Triassic of North America". Palaeontology. 54 (4): 763–772. Bibcode:2011Palgy..54..763E. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01069.x.

- ^ a b Spiekman, S.N.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Butler, R.J.; Fraser, N.C.; Maidment, S.C. (2021). "Pendraig milnerae, a new small-sized coelophysoid theropod from the Late Triassic of Wales". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (10): 210915. Bibcode:2021RSOS....810915S. doi:10.1098/rsos.210915. PMC 8493203. PMID 34754500.

- ^ a b c d e Ezcurra, Martín D; Butler, Richard J; Maidment, Susannah C R; Sansom, Ivan J; Meade, Luke E; Radley, Jonathan D (2021-01-01). "A revision of the early neotheropod genus Sarcosaurus from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian–Sinemurian) of central England". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 191 (1): 113–149. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa054. hdl:11336/160038. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ McDavid, Skye N; Bugos, Jeb E (2022-08-02). "Taxonomic notes on Megapnosaurus and 'Syntarsus' (Theropoda: Coelophysidae)". The Mosasaur (12): 1–5. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7027378.

- ^ a b c d e f g Raath, M. A. (1978). The anatomy of the Triassic theropod Syntarsus rhodesiensis (Saurischia: Podokesauridae) and a consideration of its biology.

- ^ a b Rowe, T. (1989). A new species of the theropod dinosaur Syntarsus from the Early Jurassic Kayenta Formation of Arizona. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 9(2), 125-136.

- ^ Munter, R. C., Clark, J. M., Carrano, M. T., Gaudin, T. J., Blob, R. W., & Wible, J. R. (2006). Theropod dinosaurs from the Early Jurassic of Huizachal Canyon, Mexico. Amniote paleobiology: perspectives on the evolution of mammals, birds, and reptiles, 53-75.

- ^ Bristowe, A. & M.A. Raath (2004). "A juvenile coelophysoid skull from the Early Jurassic of Zimbabwe, and the synonymy of Coelophysis and Syntarsus.(USA)". Palaeontologica Africana. 40 (40): 31–41.

- ^ Marsh, A. D.; Rowe, T. B. (2020). "A comprehensive anatomical and phylogenetic evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with descriptions of new specimens from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona". Journal of Paleontology. 94 (78): 1–103. doi:10.1017/jpa.2020.14. S2CID 220601744.

- ^ Munyikwa, D. (1999). Further material of the ceratosaurian dinosaur Syntarsus from the Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic) of South Africa.

- ^ Yates, A. M. (2005). A new theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and its implications for the early evolution of theropods. Palaeontologia africana, 41, 105-122.

- ^ Hernandez (2002). Los dinosaurios en Mexico. In Gonzalez Gonzalez and De Stefano Farias (eds.). Fosiles de Mexico: Coahuila, una Ventana a Traves del Tiempo. Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila, Saltillo. 143-153.

- ^ Ezcurra, (2012). Phylogenetic analysis of Late Triassic - Early Jurassic neotheropod dinosaurs: Implications for the early theropod radiation. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Program and Abstracts 2012, 91.

- ^ Irmis, R. B. (2004). "First report of Megapnosaurus (Theropoda: Coelophysoidea) from China". PaleoBios. 24 (3): 11–18. S2CID 85714171.

- ^ Hai-Lu You; Yoichi Azuma; Tao Wang; Ya-Ming Wang; Zhi-Ming Dong (2014). "The first well-preserved coelophysoid theropod dinosaur from Asia". Zootaxa. 3873 (3): 233–249. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3873.3.3. PMID 25544219.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-78684-190-2. OCLC 985402380.

- ^ Switek, Brian. (2013-04-16). My beloved Brontosaurus : on the road with old bones, new science, and our favorite dinosaurs (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780374135065. OCLC 795174375.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Tykoski, R. S. and Rowe, T., 2004, Ceratosauria, Chapter Three: In: The Dinosauria, Second Edition, edited by Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmolska, H., California University Press, p. 47-70.

- ^ Rowe (1989). "A new species of the theropod dinosaur Syntarsus from the Early Jurassic Kayenta Formation of Arizona". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 9 (2): 125–136. Bibcode:1989JVPal...9..125R. doi:10.1080/02724634.1989.10011748.

- ^ Tykoski, 1998. The osteology of Syntarsus kayentakatae and its implications for ceratosaurid phylogeny. Unpublished Masters Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 217 pp.

- ^ Gay, 2010. Notes on Early Mesozoic theropods. Lulu Press. 44 pp.

- ^ Mortimer, Mickey. "Coelophysoidea". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ a b Martínez, R.N.; Apaldetti, C. (2017). "A Late Norian—Rhaetian Coelophysid Neotheropod (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Quebrada Del Barro Formation, Northwestern Argentina". Ameghiniana. 54 (5): 488–505. doi:10.5710/AMGH.09.04.2017.3065. hdl:11336/65519. S2CID 133341745.

- ^ Marsh, A. D.; Rowe, T. B. (2020). "A comprehensive anatomical and phylogenetic evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with descriptions of new specimens from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona". Journal of Paleontology. 94 (78): 1–103. Bibcode:2020JPal...94S...1M. doi:10.1017/jpa.2020.14. S2CID 220601744.

- ^ Barta, D.E.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Norell, M.A. (2018). "The evolution of the manus of early theropod dinosaurs is characterized by high inter‐and intraspecific variation". Journal of Anatomy. 232 (1): 80–104. doi:10.1111/joa.12719. PMC 5735062. PMID 29114853.

- ^ Munyikwa, D.; Raath, M. A. (1999). "Further material of the ceratosaurian dinosaur Syntarsus from the Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic) of South Africa". Palaeontologia Africana. 35: 55–59.

- ^ Bond, G. (1965). "Some new fossil localities in the Karroo System of Rhodesia. Arnoldia, Series of Miscellaneous Publications". National Museum of Southern Rhodesia. 2 (11): 1–4.

- ^ M. A. Raath, 1977. The Anatomy of the Triassic Theropod Syntarsus rhodesiensis (Saurischia: Podokesauridae) and a Consideration of Its Biology. Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Salisbury, Rhodesia 1-233

- ^ a b Paul, G. S., 1988, Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, a complete Illustrated guide: New York Academy of sciences book, 464pp.

- ^ Chinsamy, A., (1994). Dinosaur bone histology: Implications and inferences. In Dino Fest (G. D. Rosenburg and D. L. Wolberg, Eds.), pp. 213-227. The Paleontological Society, Department of Geological Sciences, Univ. of Tennessee, Knoxville.

- ^ Griffin, C.T.; Nesbitt, S.J. (2016). "Anomalously high variation in postnatal development is ancestral for dinosaurs but lost in birds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (51): 14757–14762. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11314757G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1613813113. PMC 5187714. PMID 27930315.

- ^ Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407.

- ^ Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 337-363.

- ^ Raath, M. A. (1972). "First record of dinosaur footprints from Rhodesia". Arnoldia. 5 (37): 1–5.