Cleopatra Selene II (Greek: Κλεοπάτρα Σελήνη; summer 40 BC – c. 5 BC;[3] the numeration is modern) was a Ptolemaic princess, Queen of Numidia (briefly in 25 BC) and Mauretania (25 BC – 5 BC) and Queen of Cyrenaica (34 BC – 30 BC[4]). She was an important royal woman in the early Augustan age.

| Cleopatra Selene II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

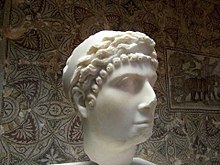

An ancient Roman bust of either Cleopatra Selene II, Queen of Mauretania, or her mother Cleopatra VII of Egypt: Archaeological Museum of Cherchell, Algeria[1] | |||||

| Queen consort of Numidia | |||||

| Tenure | 25 BC – 25 BC | ||||

| Queen consort of Mauretania | |||||

| Tenure | 25 BC – 5 BC | ||||

| Queen of Cyrenaica | |||||

| Reign | 34 BC – 30 BC | ||||

| Born | 40 BC[2] Alexandria, Egypt | ||||

| Died | c. 5 BC (aged 34-35)[2] Caesarea, Mauretania | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Juba II of Numidia | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic | ||||

| Father | Mark Antony | ||||

| Mother | Cleopatra VII Philopator | ||||

Cleopatra Selene was the only daughter of Greek Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and Roman Triumvir Mark Antony. In the Donations of Antioch and of Alexandria, she was made queen of Cyrenaica and Libya.[5][6][7] After Antony and Cleopatra's defeat at Actium and their suicides in Egypt in 30 BC, Selene and her brothers were brought to Rome and placed in the household of Octavian's sister, Octavia the Younger, a former wife of her father.

Selene married Juba II of Numidia and Mauretania. She had great influence in Mauretania's government decisions, especially regarding trade and construction projects. During their reign, the country became extremely wealthy. The couple had a son and successor, Ptolemy of Mauretania. Through their granddaughter Drusilla, the Ptolemaic line intermarried into Roman nobility for many generations.

Early life edit

Childhood edit

Cleopatra Selene was born approximately 40 BC in Egypt, as Queen Cleopatra VII's only daughter. Her second name ("moon" in Ancient Greek) opposes the second name of her twin brother, Alexander Helios ("sun" in Ancient Greek). She was raised and highly educated in Alexandria in a manner appropriate for a Ptolemaic princess. The twins were formally acknowledged by their father, Triumvir Mark Antony, during a political meeting with their mother in 37 BC. Their younger brother, Ptolemy Antony Philadelphos, was born approximately a year later. Their mother most likely planned for Selene to marry her older half-brother Caesarion, son of Cleopatra by Julius Caesar, after whom he was named.

Over the next two years, Antony bestowed a great deal of land on Cleopatra and their children under his triumviral authority. In 34 BC, during the Donations of Alexandria, huge crowds assembled to witness the couple sit on golden thrones on a silver platform with Caesarion, Cleopatra Selene, Alexander Helios, and Ptolemy Philadelphus sitting on smaller ones below them. Antony declared Cleopatra to be Queen of Kings, Caesarion to be the true son of Julius Caesar and King of Egypt, and proceeded to bestow kingdoms of their own upon Selene and her brothers. She was made ruler of Cyrenaica and Libya. Neither of the children were old enough to assume control of their lands, but it was clear that their parents intended they should do so in the future. This event, along with Antony's marriage to Cleopatra and divorce of Octavia Minor, older sister of Octavian (future Roman Emperor Caesar Augustus), marked a turning point that led to the Final War of the Roman Republic.

In 31 BC. during a naval battle at Actium, Antony and Cleopatra were defeated by Octavian. By the time Octavian arrived in Egypt in the summer of 30 BC, the couple had sent the children away. Caesarion went to India, but en route he was betrayed by his tutor, intercepted by Roman forces and executed. Cleopatra Selene, Alexander Helios, and Ptolemy Philadelphos were sent south to Thebes, but were apprehended by Roman soldiers en route and brought back to Alexandria. Meanwhile, their parents committed suicide as Octavian and his army invaded Egypt. The deaths of their mother Cleopatra VII and older half-brother Caesarion left Selene and Alexander as the nominal heirs to the throne of Egypt until the kingdom was officially annexed by the Roman Empire two weeks later, bringing the Ptolemaic Dynasty and the entirety of pharaonic Egypt to an end.

Life in Rome edit

When Octavian returned to Rome he brought the captured Cleopatra Selene and her surviving brothers with him as captives. During his triumph celebrating his conquest of Egypt, he paraded the twins dressed as the moon and the sun in heavy golden chains, behind an effigy of their mother clutching an asp to her arm. The chains were so heavy that the children were unable to walk in them, eliciting unexpected sympathy from many of the Roman onlookers.[9]

Once Egypt had ceased to exist as an independent kingdom, there remained the question of what to do with Selene and her brothers. In the absence of any surviving relative, responsibility for the children passed to Augustus, who in turn gave the siblings to Octavia to be raised in her household on the Palatine Hill.[9] They were members of an extended family that included their half-brother Iullus Antonius (their father's son with his late wife Fulvia), their half-sisters, both called Antonia (daughters of their father with Octavia), and Octavia's older children from a previous marriage, Marcus Claudius Marcellus and his two sisters Claudia Marcella Major and Claudia Marcella Minor.[citation needed] Cleopatra Selene is the only known surviving member of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[10] Her brothers are not recorded in any further historical accounts and are presumed to have died, possibly from either illness or assassination.[note 1]

Marriage and issue edit

Octavia arranged for Cleopatra Selene to marry the intellectual King Juba II of Numidia, whose father had committed suicide in 46 BC. He was sent to be raised in Caesar's household; on Caesar's death in 44 BC custody passed to Octavian, the future Augustus. The marriage likely took place in 25 BC[11] and was commemorated in an epigram that survives in its entirety:

Great neighbouring regions of the world, which divides the Nile,

Swollen from black Ethiopia, divides,

You have created common kings for both through marriage, making one race of Egyptians and Libyans.

Let the children of Kings in turn hold from their fathers a strong rule over both lands.

The couple had two children:

- Ptolemy of Mauretania born in 10 BC [12] He was named after his mother's dynasty and her younger brother. In naming her son, Cleopatra created a distinct Greek-Egyptian tone and emphasized her role as heiress of the Ptolemies in exile.

- A daughter, whose name has not survived, is mentioned in an inscription. It has been suggested that she was the Drusilla who was the first wife of Antonius Felix, but this woman was more likely a granddaughter through Ptolemy instead.[12]

A hoard of Selene's coins has been dated at 17 AD. It is traditionally believed that she was alive to mint them, but this would mean that her husband married Princess Glaphyra of Cappadocia during Selene's lifetime. Historians generally assume that Juba wouldn't have taken a second wife as a thoroughly Romanized king, arguing that if he married Glaphyra before 4 AD, then his first wife must have already been dead.[13] However, even contemporary client kings with Roman citizenship took multiple wives. It is possible that Selene and Juba separated for a time, but that their rift was mended after Juba's divorce from Glaphyra.

Queen of Mauretania edit

In 25 BC, Augustus decided to confer on Juba II and Selene the newly created client kingdom of Mauretania since Numidia was, after a brief period of status as the Roman client kingdom under king Juba II (30 - 25 BC) once again directly annexed to the Roman Empire as the part of the Roman province of Africa Proconsularis. The young rulers renamed their new capital Caesarea (modern Cherchell, Algeria), in honor of the Emperor.[15]

Mauretania was a vast territory, but lacked organization. Cleopatra Selene is said to have exercised great influence on the policies which Juba promoted. She imported many important advisers, scholars, and artists from her mother's royal court in Alexandria to serve in Caesarea. Through the couple's influence, the Mauretanian kingdom flourished.

Economy edit

Cleopatra supported Mauretanian trade. The kingdom developed a significant export throughout the Mediterranean region,[16] particularly with Spain and Italy. Their products included fish, grapes, pearls, figs, grain, wooden furniture and purple dye harvested from shellfish. Tingis (modern Tangier), a town at the Pillars of Hercules (modern Strait of Gibraltar), became a major trade centre. The value and quality of Mauretanian coins became recognised throughout the Roman Empire.

Building projects edit

Cleopatra's promotion of architecture marks a transition between the Hellenistic style and Roman. The construction and sculptural projects at Caesarea and Volubilis display a mixture of Ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman architectural styles.[16] These buildings included a lighthouse in the style of Pharos of Alexandria in the harbour, a royal palace situated in the seafront, and numerous temples dedicated to Roman and Egyptian deities. Her vigorous promotion of her mother's legacy stood in sharp contrast to the negative image being disseminated in contemporary Augustan poetry.[17]

Death edit

The couple ruled Mauretania for almost two decades until Cleopatra's death at the age of 35. Controversy surrounds her exact date of death. The following epigram by Greek epigrammatist Crinagoras of Mytilene is considered to be her eulogy:[13]

The moon herself grew dark, rising at sunset,

Covering her suffering in the night,

Because she saw her beautiful namesake, Selene,

Breathless, descending to Hades,

With her she had had the beauty of her light in common,

And mingled her own darkness with her death.

If this poem isn't simply literary license, Selene's death seems to have coincided with a lunar eclipse. If so, astronomical correlation then can be used to help pinpoint the date of her death: Lunar eclipses occurred in 9, 8, 5 and 1 BC and in AD 3, 7, 10, 11 and 14. The event in 5 BC most closely resembles the description given in the eulogy.[18] However, the date of her death is not ascertainable with any certainty. Zahi Hawass, former Director of Egyptian Antiquities, believes Cleopatra died in 8 AD.[19]

Selene was placed in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania in modern Algeria, built by her and Juba east of Caesarea and still visible. Juba died in 23 AD and was buried in the same tomb. There is a fragmentary inscription dedicated to the couple as the "King and Queen of Mauretania". Their remains have not been found at the site, perhaps due to tomb raids, possibly shortly after the mausoleum's construction; or because the structure was meant to serve as a memorial and not as a place of burial.[20]

Legacy edit

Cleopatra was survived by her husband and their son Ptolemy, who ruled Mauretania together until Juba's death in AD 23. Ptolemy then reigned until 40, when he was executed by Emperor Caligula, his mother's great nephew, who was probably jealous of Mauretania's wealth. Caligula's successor, Emperor Claudius, took advantage of Ptolemy's lack of heirs and assumed control of Mauretania, turning it into the Roman provinces of Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Tingitana. Thereafter, Cleopatra, Juba and Ptolemy were mostly forgotten.[17]

One of the two satellites of the asteroid (216) Kleopatra was named Cleoselene in her honor.

In fiction edit

- Cleopatra Selene is mentioned in the novels by Robert Graves, I, Claudius and Claudius the God.

- Cleopatra Selene is a significant character in Wallace Breem's historical novel The Legate's Daughter (1974), Phoenix/Orion Books Ltd. ISBN 0-7538-1895-7

- Cleopatra's Daughter by Andrea Ashton (1979) tells of Cleopatra Selene's early life.

- The Memoirs of Cleopatra by Margaret George (1997) ISBN 0312154305 mentions Cleopatra Selene's birth and early life with her mother.

- Querida Alejandría by María García Esperón (Bogotá 2007: Norma, ISBN 958-04-9845-8), is a novel in the form of a letter by Cleopatra Selene to the people of Alexandria.

- Cleopatra's Daughter by Michelle Moran (2009) tells the story of Cleopatra Selene's early life, from the demise of her parents through her life in Rome until her marriage to Juba II of Numidia.

- Lily of the Nile, Song of the Nile, and Daughters of the Nile, a trilogy by Stephanie Dray, tells the life story of Cleopatra Selene mixed with magical fantasy.

- Cleopatra's Moon by Vicky Alvear Shecter (2011) is a novel for teens about Cleopatra Selene. The book ends with Cleopatra's marriage to Juba II.

- Cleopatra Selene and her twin Alexander appear briefly in the television series Rome.

- Selene, córka Kleopatry by Natalia Rolleczek is a novel about Cleopatra Selene and her brothers from the death of their parents until her marriage.

- Selene is a lead character in Michael Livingston's 2015 historical fantasy novel The Shards of Heaven.[21][22]

- Cleopatra Selene is a major character in "The Daughters of Pallatine Hill", by Phyllis T. Smith (2016)

- Though identified simply as the daughter of the most famous Cleopatra, a character calling herself Patra appears in the third Night Huntress book as a vampire living in modern times, and is the novel's antagonist.

- Cleopatra Selene is the subject of the episode "Cleopatra's Daughter" in the docudrama television series Queens of Ancient Egypt which aired in 2023 on Sky History in the U.K. and Curiosity Stream in the U.S. She is portrayed as a child and adult by Fatima Ezzahra Fatih and Daiana Madeira, respectively.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ In his Roman History, Cassius Dio mentions that the brothers were spared by Augustus as a wedding present (51.15.6), but Dio's adherence to facts is debatable.

References edit

- ^ Ferroukhi, Mafoud (2001). "Marble portrait, perhaps of Cleopatra VII's daughter, Cleopatra Selene, Queen of Mauretania". In Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (eds.). Cleopatra of Egypt: from History to Myth. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (British Museum Press). p. 219. ISBN 9780691088358.

- ^ a b Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong, Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roller 2003, p. 256.

- ^ Sampson, Gareth C. (2020-08-05). Rome and Parthia: Empires at War: Ventidius, Antony and the Second Romano-Parthian War, 40-20 BC. Pen and Sword Military. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-5267-1016-1.

- ^ Roller 2003, pp. 76–81.

- ^ Grant, Michael (2011-07-14). Cleopatra: Cleopatra. Orion. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-78022-114-4.

- ^ Chauveau, Michel (2000). Egypt in the Age of Cleopatra: History and Society Under the Ptolemies. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8014-8576-3.

- ^ Roller 2003, p. 139.

- ^ a b Roller 2003, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Roller 2003, pp. 84–89.

- ^ Roller 2003, p. 4.

- ^ a b Cleopatra Selene by Chris Bennett

- ^ a b Roller 2003, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Walker, Susan (2001), "Gilded silver dish, decorated with a bust perhaps representing Cleopatra Selene", in Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (eds.), Cleopatra of Egypt: from History to Myth, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press (British Museum Press), pp. 312–313, ISBN 9780691088358.

- ^ Roller 2003, pp. 98–100.

- ^ a b Roller 2003, pp. 91–162.

- ^ a b Jane Draycott. "Cleopatra's Daughter". History Today. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Ancey 1910, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Roller 2003, p. 250.

- ^ Davies, Ethel (2009). North Africa: the Roman Coast. Chalfont St. Peter, Buckinghamshire: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-287-3, p. 11.

- ^ "The Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ "Review: The Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston". Kirkus Reviews. September 3, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

Sources edit

- Ancey, Gabriel (1910). "Sur Deux Épigrammes De Crinagoras". Revue Archéologique. 15 (Janvier–Juin): 139–141. JSTOR 41747871.

- Roller, Duane W. (2003). The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene: Royal Scholarship on Rome's African Frontier. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415305969.

- Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter, eds. (2001). Cleopatra of Egypt: from History to Myth. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (British Museum Press). ISBN 9780691088358.

- Cassius Dio – Roman History

- Plutarch – Makers of Rome – Mark Antony

- Suetonius – The Lives of the Twelve Caesars – Augustus & Caligula

- Encyclopædia Britannica – Juba II

Further reading edit

- Draycott, Jane (2022). Cleopatra's Daughter: Egyptian Princess, Roman Prisoner, African Queen. Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-324-09259-9.

- Draycott, Jane (22 May 2018). "Cleopatra's Daughter: While Antony and Cleopatra have been immortalised in history and in popular culture, their offspring have been all but forgotten. Their daughter, Cleopatra Selene, became an important ruler in her own right". History Today.

- Moran, Michelle. "Behind the Scenes of Cleopatra's Daughter Archived 2018-10-18 at the Wayback Machine".

- Roller, Duane W. (2018). Cleopatra's Daughter: And Other Royal Women of the Augustan Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190618827.