Cellulose fibers (/ˈsɛljʊloʊs, -loʊz/)[1] are fibers made with ethers or esters of cellulose, which can be obtained from the bark, wood or leaves of plants, or from other plant-based material. In addition to cellulose, the fibers may also contain hemicellulose and lignin, with different percentages of these components altering the mechanical properties of the fibers.

The main applications of cellulose fibers are in the textile industry, as chemical filters, and as fiber-reinforcement composites,[2] due to their similar properties to engineered fibers, being another option for biocomposites and polymer composites.

History

editCellulose was discovered in 1838 by the French chemist Anselme Payen, who isolated it from plant matter and determined its chemical formula.[3] Cellulose was used to produce the first successful thermoplastic polymer, celluloid, by Hyatt Manufacturing Company in 1870. Production of rayon ("artificial silk") from cellulose began in the 1890s, and cellophane was invented in 1912. In 1893, Arthur D. Little of Boston, invented yet another cellulosic product, acetate, and developed it as a film. The first commercial textile uses for acetate in fiber form were developed by the Celanese Company in 1924. Hermann Staudinger determined the polymer structure of cellulose in 1920. The compound was first chemically synthesized (without the use of any biologically derived enzymes) in 1992, by Kobayashi and Shoda.

Cellulose structure

editCellulose is a polymer made of repeating glucose molecules attached end to end.[4] A cellulose molecule may be from several hundred to over 10,000 glucose units long. Cellulose is similar in form to complex carbohydrates like starch and glycogen. These polysaccharides are also made from multiple subunits of glucose. The difference between cellulose and other complex carbohydrate molecules is how the glucose molecules are linked together. In addition, cellulose is a straight chain polymer, and each cellulose molecule is long and rod-like. This differs from starch, which is a coiled molecule. A result of these differences in structure is that, compared to starch and other carbohydrates, cellulose cannot be broken down into its glucose subunits by any enzymes produced by animals.

Types

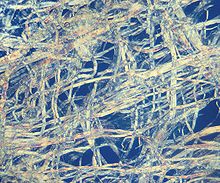

editNatural cellulose fibers

editNatural cellulose fibers are still recognizable as being from a part of the original plant because they are only processed as much as needed to clean the fibers for use.[citation needed] For example, cotton fibers look like the soft fluffy cotton balls that they come from. Linen fibers look like the strong fibrous strands of the flax plant. All "natural" fibers go through a process where they are separated from the parts of the plant that are not used for the end product, usually through harvesting, separating from chaff, scouring, etc. The presence of linear chains of thousands of glucose units linked together allows a great deal of hydrogen bonding between OH groups on adjacent chains, causing them to pack closely into cellulose fibers. As a result, cellulose exhibits little interaction with water or any other solvent. Cotton and wood, for example, are completely insoluble in water and have considerable mechanical strength. Since cellulose does not have a helical structure like amylose, it does not bind to iodine to form a colored product.

Manufactured cellulose fibers

editManufactured cellulose fibers come from plants that are processed into a pulp and then extruded in the same ways that synthetic fibers like polyester or nylon are made. Rayon or viscose is one of the most common "manufactured" cellulose fibers, and it can be made from wood pulp.

Structure and properties

editNatural fibers are composed by microfibrils of cellulose in a matrix of hemicellulose and lignin. This type of structure and the chemical composition of them is responsible for the mechanical properties that can be observed. Because the natural fibers make hydrogen bonds between the long chains, they have the necessary stiffness and strength.

Chemical composition

editThe major constituents of natural fibers (lignocelluloses) are cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, pectin and ash. The percentage of each component varies for each different type of fiber, however, generally, are around 60-80% cellulose, 5–20% lignin, and 20% of moisture, besides hemicellulose and a small percent of residual chemical components. The properties of the fiber change depending on the amount of each component, since the hemicellulose is responsible for the moisture absorption, bio- and thermal degradation whereas lignin ensures thermal stability but is responsible for the UV degradation. The chemical composition of common natural fibers are shown below;[5] these vary depending on whether the fiber is a bast fiber (obtained from the bark), a core fiber (obtained from the wood), or a leaf fiber (obtained from the leaves).

| Type of fiber | Cellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Pectin (%) | Ash (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bast fiber | Fiber flax | 71 | 2.2 | 18.6 – 20.6 | 2.3 | – |

| Seed flax | 43–47 | 21–23 | 24–26 | – | 5 | |

| Kenaf | 31–57 | 15–19 | 21.5–23 | – | 2–5 | |

| Jute | 45–71.5 | 12–26 | 13.6–21 | 0.2 | 0.5–2 | |

| Hemp | 57–77 | 3.7–13 | 14–22.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| Ramie | 68.6–91 | 0.6–0.7 | 5–16.7 | 1.9 | – | |

| Core fiber | Kenaf | 37–49 | 15–21 | 18–24 | – | 2–4 |

| Jute | 41–48 | 21–24 | 18–22 | – | 0.8 | |

| Leaf fiber | Abaca | 56–63 | 7–9 | 15–17 | – | 3 |

| Sisal | 47–78 | 7–11 | 10–24 | 10 | 0.6–1 | |

| Henequen | 77.6 | 13.1 | 4–8 | – | – | |

Mechanical properties

editCellulose fiber response to mechanical stresses change depending on fiber type and chemical structure present. Information about main mechanical properties are shown in the chart below and can be compared to properties of commonly used fibers such glass fiber, aramid fiber, and carbon fiber.

| Fiber | Density (g/cm3) | Elongation (%) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Young's modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton | 1.5–1.6 | 3.0–10.0 | 287–597 | 5.5–12.6 |

| Jute | 1.3–1.46 | 1.5–1.8 | 393–800 | 10–30 |

| Flax | 1.4–1.5 | 1.2–3.2 | 345–1500 | 27.6–80 |

| Hemp | 1.48 | 1.6 | 550–900 | 70 |

| Ramie | 1.5 | 2.0–3.8 | 220–938 | 44–128 |

| Sisal | 1.33–1.5 | 2.0–14 | 400–700 | 9.0–38.0 |

| Coir | 1.2 | 15.0–30.0 | 175–220 | 4.0–6.0 |

| Softwood kraft | 1.5 | – | 1000 | 40.0 |

| E–glass | 2.5 | 2.5–3.0 | 2000–3500 | 70.0 |

| S–glass | 2.5 | 2.8 | 4570 | 86.0 |

| Aramid | 1.4 | 3.3–3.7 | 3000–3150 | 63.0–67.0 |

| Carbon | 1.4 | 1.4–1.8 | 4000 | 230.0–240.0 |

Surface and interfacial properties

editHydrophilicity, roughness and surface charge determine the interaction of cellulose fibers with an aqueous environment. Already in 1950, the charge at the interface between cotton as the predominant cellulose fiber and an aqueous surrounding was investigated by the streaming potential method to assess the surface zeta potential.[6] Due to the high swelling propensity of lignocellulosic fibers, a correlation between the zeta potential and the water uptake capability has been observed.[7] Even for the use of waste fibers as a reinforcement in composite materials, sized fibers have been probed by an aqueous test solution.[8] A review on the electrokinetic properties of natural fibers including cellulose and lignocellulosic fibers is found in the Handbook of Natural Fibers.[9]

Applications

editComposite materials

edit| Matrix | Fiber |

|---|---|

| Epoxy | Abaca, bamboo, jute |

| Natural rubber | Coir, sisal |

| Nitrile rubber | Jute |

| Phenol-formaldehyde | Jute |

| Polyethylene | Kenaf, pineapple, sisal, wood fiber |

| Polypropylene | Flax, jute, kenaf, sunhemp, wheat straw, wood fiber |

| Polystyrene | Wood |

| Polyurethane | Wood |

| Polyvinyl chloride | Wood |

| Polyester | Banana, jute, pineapple, sunhemp |

| Styrene-butadiene | Jute |

| Rubber | Oil palm |

Composite materials are a class of material most often made by the combination of a fiber with a binder material (matrix). This combination mixes the properties of the fiber with the matrix to create a new material that may be stronger than the fiber alone. When combined with polymers, cellulose fibers are used to create some fiber-reinforced materials such as biocomposites and fiber-reinforced plastics. The table displays different polymer matrices and the cellulose fibers they are often mixed with.[10]

Since macroscopic characteristics of fibers influence the behavior of the resulting composite, the following physical and mechanical properties are of particular interest:

- Dimensions: The relationship between the length and diameter of the fibers is a determining factor in the transfer of efforts to the matrix. Additionally, the irregular cross-section and fibrillated appearance of plant fibers helps anchor them within a fragile matrix.

- Void volume and water absorption: Fibers are fairly porous with a large volume of internal voids. As a result, when the fibers are immersed in the binding material, they absorb a large amount of matrix. High absorption can cause fiber shrinkage and matrix swelling. However, a high void volume contributes to reduced weight, increased acoustic absorption, and low thermal conductivity of the final composite material.

- Tensile strength: Similar, on average, to the polypropylene's fibers.[clarification needed]

- Elastic modulus: Cellulosic fibers have a low modulus of elasticity. This determines its use in building components working in post-cracked stage, with high energy absorption and resistance to dynamic forces.[clarification needed]

Textile

editIn the textile industry regenerated cellulose is used as fibers such as rayon, (including modal, and the more recently developed Lyocell). Cellulose fibers are manufactured from dissolving pulp.[11] Cellulose-based fibers are of two types, regenerated or pure cellulose such as from the cupro-ammonium process and modified cellulose such as the cellulose acetates.

The first artificial fiber, commercially promoted as artificial silk, became known as viscose around 1894, and finally rayon in 1924. A similar product known as cellulose acetate was discovered in 1865. Rayon and acetate are both artificial fibers, but not fully synthetic, being a product of a chemically digested feedstock comprising natural wood. They are also not an artificial construction of silk, which is a fibrous polymer of animal proteins. Although these artificial fibers were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century, successful modern manufacture began much later.

Filtration

editThe cellulose fibers infiltration/filter aid applications can provide a protective layer to filter elements as powdered cellulose, besides promoting improved throughput and clarity.[citation needed] As ashless and non-abrasive filtration, make cleanup effortless after the filtering process without damage in pumps or valves. They effectively filter metallic impurities and absorb up to 100% of emulsified oil and boiler condensates. In general, cellulose fibers in filtration applications can greatly improve filtration performance when used as a primary or remedial precoat in the following ways:

- Bridging gaps in the filter septum and small mechanical leaks in the gaskets and leaf seats

- Improving the stability of the filter-aid cake to make it more resistant to pressure bumps and interruptions

- Creating a more uniform precoat with no cracks for more effective filtration surface area

- Improving cake release and reducing cleaning requirements

- Preventing fine particulate bleed-through

- Precoating easily and rapidly and reducing soluble contamination

Comparison with other fibers

editIn comparison with engineered fibers, cellulose fibers have important advantages as low density, low cost, they can be recyclable, and are biodegradable.[12] Due to its advantages cellulose fibers can be used as a substituent for glass fibers in composites materials.

Environmental issues

editWhat is often marketed as "bamboo fiber"[broken anchor] is actually not the fibers that grow in their natural form from the bamboo plants, but instead a highly processed bamboo pulp that is extruded as fibers.[11] Although the process is not as environmentally friendly as "bamboo fiber" appears, planting & harvesting bamboo for fiber can, in certain cases, be more sustainable and environmentally friendly than harvesting slower growing trees and clearing existing forest habitats for timber plantations.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Cellulose fiber". The Free Online Dictionary. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ Ardanuy, Mònica; Claramunt, Josep; Toledo Filho, Romildo Dias (2015). "Cellulosic fiber reinforced cement-based composites: A review of recent research". Construction and Building Materials. 79: 115–128. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.01.035.

- ^ Cellulose: molecular and structural biology: selected articles on the synthesis, structure, and applications of cellulose. Brown, R. Malcolm (Richard Malcolm), 1939-, Saxena, I. M. (Inder M.). Dordrecht: Springer. 2007. ISBN 9781402053801. OCLC 187314758.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Carbohydrates - Cellulose". Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ Xue, L. G.; Tabil, L.; Panigrahi, S. (2007). "Chemical Treatments of Natural Fiber for Use in Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Review". Journal of Polymers and the Environment. 15 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1007/s10924-006-0042-3. S2CID 96323385.

- ^ Mason, S. G.; Goring, D. A. I. (June 1, 1950). "Electrokinetic Properties of Cellulose Fibers: Ii. Zeta-Potential Measurements by the Stream-Compression Method". Canadian Journal of Research. 28b (6): 323–338. doi:10.1139/cjr50b-040. ISSN 1923-4287.

- ^ Bismarck, Alexander; Aranberri-Askargorta, Ibon; Springer, Jürgen; Lampke, Thomas; Wielage, Bernhard; Stamboulis, Artemis; Shenderovich, Ilja; Limbach, Hans-Heinrich (2002). "Surface characterization of flax, hemp and cellulose fibers; Surface properties and the water uptake behavior". Polymer Composites. 23 (5): 872–894. doi:10.1002/pc.10485. ISSN 0272-8397.

- ^ Pothan, Laly A.; Bellman, Cornelia; Kailas, Lekshmi; Thomas, Sabu (January 1, 2002). "Influence of chemical treatments on the electrokinetic properties of cellulose fibres". Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology. 16 (2): 157–178. doi:10.1163/156856102317293687. ISSN 0169-4243. S2CID 94420824.

- ^ Luxbacher, Thomas (January 1, 2020), Kozłowski, Ryszard M.; Mackiewicz-Talarczyk, Maria (eds.), "9 - Electrokinetic properties of natural fibres", Handbook of Natural Fibres (Second Edition), The Textile Institute Book Series, Woodhead Publishing, pp. 323–353, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818782-1.00009-2, ISBN 978-0-12-818782-1

- ^ Saheb, D. N.; Jog, J. P. (1999). "Natural fiber polymer composites: A review". Advances in Polymer Technology. 18 (4): 351–363. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2329(199924)18:4<351::AID-ADV6>3.0.CO;2-X.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Kate (2008). Sustainable fashion and textiles design journeys. London: Earthscan. ISBN 9781849772778. OCLC 186246363.

- ^ Mohanty, A. K.; Misra, M.; Hinrichsen, G. (2000). "Biofibres, biodegradable polymers and biocomposites: An overview". Macromolecular Materials and Engineering. 276–277 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1439-2054(20000301)276:1<1::AID-MAME1>3.0.CO;2-W.

External links

edit- Dissolving of Cellulosics Archived April 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine