Cardiology (from Ancient Greek καρδίᾱ (kardiā) 'heart' and -λογία (-logia) 'study') is the study of the heart. Cardiology is a branch of medicine that deals with disorders of the heart and the cardiovascular system. The field includes medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart disease, and electrophysiology. Physicians who specialize in this field of medicine are called cardiologists, a sub-specialty of internal medicine. Pediatric cardiologists are pediatricians who specialize in cardiology. Physicians who specialize in cardiac surgery are called cardiothoracic surgeons or cardiac surgeons, a specialty of general surgery.[1]

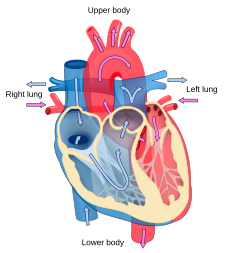

Blood flow diagram of the human heart. Blue components indicate de-oxygenated blood pathways and red components indicate oxygenated blood pathways. | |

| System | Cardiovascular |

|---|---|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Significant diseases | |

| Significant tests | Blood tests, electrophysiology study, cardiac imaging, ECG, echocardiograms, stress test |

| Specialist | Cardiologist |

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names |

|

Occupation type | Specialty |

Activity sectors | Medicine, Surgery |

| Description | |

Education required |

|

Fields of employment | Hospitals, Clinics |

Specializations

editAll cardiologists in the branch of medicine study the disorders of the heart, but the study of adult and child heart disorders each require different training pathways. Therefore, an adult cardiologist (often simply called "cardiologist") is inadequately trained to take care of children, and pediatric cardiologists are not trained to treat adult heart disease. Surgical aspects outside of cardiac rhythm device implant are not included in cardiology and are in the domain of cardiothoracic surgery. For example, coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), cardiopulmonary bypass and valve replacement are surgical procedures performed by surgeons, not cardiologists. Typically a cardiologist would first identify who is in need of cardiac surgery and refer them to a cardiac surgeon for the procedure. However, some invasive procedures such as cardiac catheterization and pacemaker implantation are performed by cardiologists.

Adult cardiology

editCardiology is a specialty of internal medicine.

To become a cardiologist in the United States, a three-year residency in internal medicine is followed by a three-year fellowship in cardiology. It is possible to specialize further in a sub-specialty. Recognized sub-specialties in the U.S. by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education are clinical cardiac electrophysiology, interventional cardiology, adult congenital heart disease, and advanced heart failure and transplant cardiology. Cardiologists may further become certified in echocardiography by the National Board of Echocardiography,[2] in nuclear cardiology by the Certification Board of Nuclear Cardiology, in cardiovascular computed tomography by the Certification Board of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography in cardiovascular MRI by the Certification Board of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.[3] Recognized subspecialties in the U.S. by the American Osteopathic Association Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists include clinical cardiac electrophysiology and interventional cardiology.[4]

In India, a three-year residency in General Medicine or Pediatrics after M.B.B.S. and then three years of residency in cardiology are needed to be a D.M. (holder of a Doctorate of Medicine [D.M.])/Diplomate of National Board (DNB) in Cardiology.[citation needed]

Per Doximity, adult cardiologists earn an average of $436,849 per year in the U.S.[5]

Cardiac electrophysiology

editCardiac electrophysiology is the science of elucidating, diagnosing, and treating the electrical activities of the heart. The term is usually used to describe studies of such phenomena by invasive (intracardiac) catheter recording of spontaneous activity as well as of cardiac responses to programmed electrical stimulation (PES). These studies are performed to assess complex arrhythmias, elucidate symptoms, evaluate abnormal electrocardiograms, assess risk of developing arrhythmias in the future, and design treatment. These procedures increasingly include therapeutic methods (typically radiofrequency ablation, or cryoablation) in addition to diagnostic and prognostic procedures.

Other therapeutic modalities employed in this field include antiarrhythmic drug therapy and implantation of pacemakers and automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (AICD).[6][7]

The cardiac electrophysiology study typically measures the response of the injured or cardiomyopathic myocardium to PES on specific pharmacological regimens in order to assess the likelihood that the regimen will successfully prevent potentially fatal sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) in the future. Sometimes a series of electrophysiology-study drug trials must be conducted to enable the cardiologist to select the one regimen for long-term treatment that best prevents or slows the development of VT or VF following PES. Such studies may also be conducted in the presence of a newly implanted or newly replaced cardiac pacemaker or AICD.[6]

Clinical cardiac electrophysiology

editClinical cardiac electrophysiology is a branch of the medical specialty of cardiology and is concerned with the study and treatment of rhythm disorders of the heart. Cardiologists with expertise in this area are usually referred to as electrophysiologists. Electrophysiologists are trained in the mechanism, function, and performance of the electrical activities of the heart. Electrophysiologists work closely with other cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to assist or guide therapy for heart rhythm disturbances (arrhythmias). They are trained to perform interventional and surgical procedures to treat cardiac arrhythmia.[8]

The training required to become an electrophysiologist is long and requires eight years after medical school (within the U.S.). Three years of internal medicine residency, three years of cardiology fellowship, and two years of clinical cardiac electrophysiology.[9]

Cardiogeriatrics

editCardiogeriatrics, or geriatric cardiology, is the branch of cardiology and geriatric medicine that deals with the cardiovascular disorders in elderly people.

Cardiac disorders such as coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, are common and are a major cause of mortality in elderly people.[10][11] Vascular disorders such as atherosclerosis and peripheral arterial disease cause significant morbidity and mortality in aged people.[12][13]

Imaging

editCardiac imaging includes echocardiography (echo), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR), and computed tomography of the heart. Those who specialize in cardiac imaging may undergo more training in all imaging modes or focus on a single imaging modality.

Echocardiography (or "echo") uses standard two-dimensional, three-dimensional, and Doppler ultrasound to create images of the heart. It is used to evaluate and quantify cardiac size and function, valvular function, and can assist with diagnosis and treatment of conditions including heart failure, heart attack, valvular heart disease, congenital heart defects, pericardial disease, and aortic disease. Those who specialize in echo may spend a significant amount of their clinical time reading echos and performing transesophageal echo, in particular using the latter during procedures such as insertion of a left atrial appendage occlusion device. Transesophageal echo provides higher spatial resolution than trans thoracic echocardiography and because the probe is located in the esophagus, it is not limited by attenuation due to anterior chest structures such as the ribs, chest wall, breasts, lungs that can hinder the quality of trans thoracic echocardiography. It is generally indicated for a variety of indications including: when the standard transthoracic echocardiogram is non diagnostic, for detailed evaluation of abnormalities that are typically in the far field, such as the aorta, left atrial appendage, evaluation of native or prosthetic heart valves, evaluation of cardiac masses, evaluation of endocarditis, valvular abscesses, or for the evaluation of cardiac source of embolus. It is frequently used in the setting of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter to facilitate the clinical decision with regard to anticoagulation, cardioversion and/or radio frequency ablation.[14]

Cardiac MRI utilizes special protocols to image heart structure and function with specific sequences for certain diseases such as hemochromatosis and amyloidosis.

Cardiac CT utilizes special protocols to image heart structure and function with particular emphasis on coronary arteries.

Interventional cardiology

editInterventional cardiology is a branch of cardiology that deals specifically with the catheter based treatment of structural heart diseases.[15] A large number of procedures can be performed on the heart by catheterization, including angiogram, angioplasty, atherectomy, and stent implantation. These procedures all involve insertion of a sheath into the femoral artery or radial artery (but, in practice, any large peripheral artery or vein) and cannulating the heart under X-ray visualization (most commonly fluoroscopy). This cannulation allows indirect access to the heart, bypassing the trauma caused by surgical opening of the chest.

The main advantages of using the interventional cardiology or radiology approach are the avoidance of the scars and pain, and long post-operative recovery. Additionally, interventional cardiology procedure of primary angioplasty is now the gold standard of care for an acute myocardial infarction. This procedure can also be done proactively, when areas of the vascular system become occluded from atherosclerosis. The Cardiologist will thread this sheath through the vascular system to access the heart. This sheath has a balloon and a tiny wire mesh tube wrapped around it, and if the cardiologist finds a blockage or stenosis, they can inflate the balloon at the occlusion site in the vascular system to flatten or compress the plaque against the vascular wall. Once that is complete a stent is placed as a type of scaffold to hold the vasculature open permanently.

Cardiomyopathy/heart failure

editA relatively newer specialization of cardiology is in the field of heart failure and heart transplant. Cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart muscle that make it larger or stiffer, sometimes making the heart worse at pumping blood.[16] Specialization of general cardiology to just that of the cardiomyopathies leads to also specializing in heart transplant and pulmonary hypertension.

Cardiooncology

editA recent specialization of cardiology is that of cardiooncology. This area specializes in the cardiac management in those with cancer and in particular those with plans for chemotherapy or those who have experienced cardiac complications of chemotherapy.

Preventive cardiology and cardiac rehabilitation

editIn recent times, the focus is gradually shifting to preventive cardiology due to increased cardiovascular disease burden at an early age. According to the WHO, 37% of all premature deaths are due to cardiovascular diseases and out of this, 82% are in low and middle income countries.[17] Clinical cardiology is the sub specialty of cardiology which looks after preventive cardiology and cardiac rehabilitation. Preventive cardiology also deals with routine preventive checkup though noninvasive tests, specifically electrocardiography, fasegraphy, stress tests, lipid profile and general physical examination to detect any cardiovascular diseases at an early age, while cardiac rehabilitation is the upcoming branch of cardiology which helps a person regain their overall strength and live a normal life after a cardiovascular event. A subspecialty of preventive cardiology is sports cardiology. Because heart disease is the leading cause of death in the world including United States (cdc.gov), national health campaigns and randomized control research has developed to improve heart health.

Pediatric cardiology

editHelen B. Taussig is known as the founder of pediatric cardiology. She became famous through her work with Tetralogy congenital heart defect in which oxygenated and deoxygenated blood enters the circulatory system resulting from a ventricular septal defect (VSD) right beneath the aorta. This condition causes newborns to have a bluish-tint, cyanosis, and have a deficiency of oxygen to their tissues, hypoxemia. She worked with Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas at the Johns Hopkins Hospital where they experimented with dogs to look at how they would attempt to surgically cure these "blue babies". They eventually figured out how to do just that by the anastomosis of the systemic artery to the pulmonary artery and called this the Blalock-Taussig Shunt.[18]

Tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, double outlet right ventricle, transposition of the great arteries, persistent truncus arteriosus, and Ebstein's anomaly are various congenital cyanotic heart diseases, in which the blood of the newborn is not oxygenated efficiently, due to the heart defect.

Adult congenital heart disease

editAs more children with congenital heart disease are surviving into adulthood, a hybrid of adult and pediatric cardiology has emerged called adult congenital heart disease (ACHD). This field can be entered as either adult or pediatric cardiology. ACHD specializes in congenital diseases in the setting of adult diseases (e.g., coronary artery disease, COPD, diabetes) that is, otherwise, atypical for adult or pediatric cardiology.

The heart

editAs the center focus of cardiology, the heart has numerous anatomical features (e.g., atria, ventricles, heart valves) and numerous physiological features (e.g., systole, heart sounds, afterload) that have been encyclopedically documented for many centuries. The heart is located in the middle of the abdomen with its tip slightly towards the left side of the abdomen.

Disorders of the heart lead to heart disease and cardiovascular disease and can lead to a significant number of deaths: cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. and caused 24.95% of total deaths in 2008.[19]

The primary responsibility of the heart is to pump blood throughout the body. It pumps blood from the body — called the systemic circulation — through the lungs — called the pulmonary circulation — and then back out to the body. This means that the heart is connected to and affects the entirety of the body. Simplified, the heart is a circuit of the circulation.[citation needed] While plenty is known about the healthy heart, the bulk of study in cardiology is in disorders of the heart and restoration, and where possible, of function.

The heart is a muscle that squeezes blood and functions like a pump. The heart's systems can be classified as either electrical or mechanical, and both of these systems are susceptible to failure or dysfunction.

The electrical system of the heart is centered on the periodic contraction (squeezing) of the muscle cells that is caused by the cardiac pacemaker located in the sinoatrial node. The study of the electrical aspects is a sub-field of electrophysiology called cardiac electrophysiology and is epitomized with the electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG). The action potentials generated in the pacemaker propagate throughout the heart in a specific pattern. The system that carries this potential is called the electrical conduction system. Dysfunction of the electrical system manifests in many ways and may include Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, ventricular fibrillation, and heart block.[20]

The mechanical system of the heart is centered on the fluidic movement of blood and the functionality of the heart as a pump. The mechanical part is ultimately the purpose of the heart and many of the disorders of the heart disrupt the ability to move blood. Heart failure is one condition in which the mechanical properties of the heart have failed or are failing, which means insufficient blood is being circulated. Failure to move a sufficient amount of blood through the body can cause damage or failure of other organs and may result in death if severe.[21]

Coronary circulation

editCoronary circulation is the circulation of blood in the blood vessels of the heart muscle (the myocardium). The vessels that deliver oxygen-rich blood to the myocardium are known as coronary arteries. The vessels that remove the deoxygenated blood from the heart muscle are known as cardiac veins. These include the great cardiac vein, the middle cardiac vein, the small cardiac vein and the anterior cardiac veins.

As the left and right coronary arteries run on the surface of the heart, they can be called epicardial coronary arteries. These arteries, when healthy, are capable of autoregulation to maintain coronary blood flow at levels appropriate to the needs of the heart muscle. These relatively narrow vessels are commonly affected by atherosclerosis and can become blocked, causing angina or myocardial infarction (a.k.a., a heart attack). The coronary arteries that run deep within the myocardium are referred to as subendocardial.

The coronary arteries are classified as "end circulation", since they represent the only source of blood supply to the myocardium; there is very little redundant blood supply, which is why blockage of these vessels can be so critical.

Cardiac examination

editThe cardiac examination (also called the "precordial exam"), is performed as part of a physical examination, or when a patient presents with chest pain suggestive of a cardiovascular pathology. It would typically be modified depending on the indication and integrated with other examinations especially the respiratory examination.[citation needed]

Like all medical examinations, the cardiac examination follows the standard structure of inspection, palpation and auscultation.[22][23]

Heart disorders

editCardiology is concerned with the normal functionality of the heart and the deviation from a healthy heart. Many disorders involve the heart itself, but some are outside of the heart and in the vascular system. Collectively, the two are jointly termed the cardiovascular system, and diseases of one part tend to affect the other.

Coronary artery disease

editCoronary artery disease, also known as "ischemic heart disease",[24] is a group of diseases that includes: stable angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and is one of the causes of sudden cardiac death.[25] It is within the group of cardiovascular diseases of which it is the most common type.[26] A common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may travel into the shoulder, arm, back, neck, or jaw.[27] Occasionally it may feel like heartburn. Usually symptoms occur with exercise or emotional stress, last less than a few minutes, and get better with rest.[27] Shortness of breath may also occur and sometimes no symptoms are present.[27] The first sign is occasionally a heart attack.[28] Other complications include heart failure or an irregular heartbeat.[28]

Risk factors include: high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, and excessive alcohol, among others.[29][30] Other risks include depression.[31] The underlying mechanism involves atherosclerosis of the arteries of the heart. A number of tests may help with diagnoses including: electrocardiogram, cardiac stress testing, coronary computed tomographic angiography, and coronary angiogram, among others.[32]

Prevention is by eating a healthy diet, regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight and not smoking.[33] Sometimes medication for diabetes, high cholesterol, or high blood pressure are also used.[33] There is limited evidence for screening people who are at low risk and do not have symptoms.[34] Treatment involves the same measures as prevention.[35][36] Additional medications such as antiplatelets including aspirin, beta blockers, or nitroglycerin may be recommended.[36] Procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) may be used in severe disease.[36][37] In those with stable CAD it is unclear if PCI or CABG in addition to the other treatments improve life expectancy or decreases heart attack risk.[38]

In 2013 CAD was the most common cause of death globally, resulting in 8.14 million deaths (16.8%) up from 5.74 million deaths (12%) in 1990.[26] The risk of death from CAD for a given age has decreased between 1980 and 2010 especially in developed countries.[39] The number of cases of CAD for a given age has also decreased between 1990 and 2010.[40] In the U.S. in 2010 about 20% of those over 65 had CAD, while it was present in 7% of those 45 to 64, and 1.3% of those 18 to 45.[41] Rates are higher among men than women of a given age.[41]

Cardiomyopathy

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2021) |

Heart failure, or formally cardiomyopathy, is the impaired function of the heart, and there are numerous causes and forms of heart failure.

The causes of cardiomyopathy can be genetic, viral, or lifestyle-related. Key symptoms of cardiomyopathy include shortness of breath, fatigue, and irregular heartbeats. Understanding the specific function of cardiac muscle is crucial, as the heart muscle's main role is to pump blood throughout the body efficiently.[42]

Cardiac arrhythmia

editCardiac arrhythmia, also known as "cardiac dysrhythmia" or "irregular heartbeat", is a group of conditions in which the heartbeat is too fast, too slow, or irregular in its rhythm. A heart rate that is too fast – above 100 beats per minute in adults – is called tachycardia. A heart rate that is too slow – below 60 beats per minute – is called bradycardia.[43] Many types of arrhythmia present no symptoms. When symptoms are present, they may include palpitations, or feeling a pause between heartbeats. More serious symptoms may include lightheadedness, passing out, shortness of breath, or chest pain.[44] While most types of arrhythmia are not serious, some predispose a person to complications such as stroke or heart failure.[43][45] Others may result in cardiac arrest.[45]

There are four main types of arrhythmia: extra beats, supraventricular tachycardias, ventricular arrhythmias, and bradyarrhythmias. Extra beats include premature atrial contractions, premature ventricular contractions, and premature junctional contractions. Supraventricular tachycardias include atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Ventricular arrhythmias include ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia.[45][46] Arrhythmias are due to problems with the electrical conduction system of the heart.[43] Arrhythmias may occur in children; however, the normal range for the heart rate is different and depends on age.[45] A number of tests can help diagnose arrhythmia, including an electrocardiogram and Holter monitor.[47]

Most arrhythmias can be effectively treated.[43] Treatments may include medications, medical procedures such as a pacemaker, and surgery. Medications for a fast heart rate may include beta blockers or agents that attempt to restore a normal heart rhythm such as procainamide. This later group may have more significant side effects especially if taken for a long period of time. Pacemakers are often used for slow heart rates. Those with an irregular heartbeat are often treated with blood thinners to reduce the risk of complications. Those who have severe symptoms from an arrhythmia may receive urgent treatment with a jolt of electricity in the form of cardioversion or defibrillation.[48]

Arrhythmia affects millions of people.[49] In Europe and North America, as of 2014, atrial fibrillation affects about 2% to 3% of the population.[50] Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter resulted in 112,000 deaths in 2013, up from 29,000 in 1990.[26] Sudden cardiac death is the cause of about half of deaths due to cardiovascular disease or about 15% of all deaths globally.[51] About 80% of sudden cardiac death is the result of ventricular arrhythmias.[51] Arrhythmias may occur at any age but are more common among older people.[49]

Cardiac arrest

editCardiac arrest is a sudden stop in effective blood flow due to the failure of the heart to contract effectively.[52] Symptoms include loss of consciousness and abnormal or absent breathing.[53][54] Some people may have chest pain, shortness of breath, or nausea before this occurs.[54] If not treated within minutes, death usually occurs.[52]

The most common cause of cardiac arrest is coronary artery disease. Less common causes include major blood loss, lack of oxygen, very low potassium, heart failure, and intense physical exercise. A number of inherited disorders may also increase the risk including long QT syndrome. The initial heart rhythm is most often ventricular fibrillation.[55] The diagnosis is confirmed by finding no pulse.[53] While a cardiac arrest may be caused by heart attack or heart failure these are not the same.[52]

Prevention includes not smoking, physical activity, and maintaining a healthy weight.[56] Treatment for cardiac arrest is immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and, if a shockable rhythm is present, defibrillation.[57] Among those who survive targeted temperature management may improve outcomes.[58] An implantable cardiac defibrillator may be placed to reduce the chance of death from recurrence.[56]

In the United States, cardiac arrest outside of hospital occurs in about 13 per 10,000 people per year (326,000 cases). In hospital cardiac arrest occurs in an additional 209,000[59] Cardiac arrest becomes more common with age. It affects males more often than females.[60] The percentage of people who survive with treatment is about 8%. Many who survive have significant disability. Many U.S. television shows, however, have portrayed unrealistically high survival rates of 67%.[61]

Hypertension

editHypertension, also known as "high blood pressure", is a long term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated.[62] High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms.[63] Long term high blood pressure, however, is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, vision loss, and chronic kidney disease.[64][65]

Lifestyle factors can increase the risk of hypertension. These include excess salt in the diet, excess body weight, smoking, and alcohol consumption.[63][66] Hypertension can also be caused by other diseases, or occur as a side-effect of drugs.[67]

Blood pressure is expressed by two measurements, the systolic and diastolic pressures, which are the maximum and minimum pressures, respectively.[63] Normal blood pressure when at rest is within the range of 100–140 millimeters mercury (mmHg) systolic and 60–90 mmHg diastolic.[68] High blood pressure is present if the resting blood pressure is persistently at or above 140/90 mmHg for most adults.[66] Different numbers apply to children.[69] When diagnosing high blood pressure, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring over a 24-hour period appears to be more accurate than "in-office" blood pressure measurement at a physician's office or other blood pressure screening location.[62][66][70]

Lifestyle changes and medications can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of health complications.[71] Lifestyle changes include weight loss, decreased salt intake, physical exercise, and a healthy diet.[66] If changes in lifestyle are insufficient, blood pressure medications may be used.[71] A regimen of up to three medications effectively controls blood pressure in 90% of people.[66] The treatment of moderate to severe high arterial blood pressure (defined as >160/100 mmHg) with medication is associated with an improved life expectancy and reduced morbidity.[72] The effect of treatment for blood pressure between 140/90 mmHg and 160/100 mmHg is less clear, with some studies finding benefits[73][74] while others do not.[75] High blood pressure affects between 16% and 37% of the population globally.[66] In 2010, hypertension was believed to have been a factor in 18% (9.4 million) deaths.[76]

Essential vs Secondary hypertension

editEssential hypertension is the form of hypertension that by definition has no identifiable cause. It is the most common type of hypertension, affecting 95% of hypertensive patients,[77][78][79][80] it tends to be familial and is likely to be the consequence of an interaction between environmental and genetic factors. Prevalence of essential hypertension increases with age, and individuals with relatively high blood pressure at younger ages are at increased risk for the subsequent development of hypertension. Hypertension can increase the risk of cerebral, cardiac, and renal events.[81]

Secondary hypertension is a type of hypertension which is caused by an identifiable underlying secondary cause. It is much less common than essential hypertension, affecting only 5% of hypertensive patients. It has many different causes including endocrine diseases, kidney diseases, and tumors. It also can be a side effect of many medications.[82]

Complications of hypertension

editComplications of hypertension are clinical outcomes that result from persistent elevation of blood pressure.[83] Hypertension is a risk factor for all clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis since it is a risk factor for atherosclerosis itself.[84][85][86][87][88] It is an independent predisposing factor for heart failure,[89][90] coronary artery disease,[91][92] stroke,[83] renal disease,[93][94][95] and peripheral arterial disease.[96][97] It is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, in industrialized countries.[98]

Congenital heart defects

editA congenital heart defect, also known as a "congenital heart anomaly" or "congenital heart disease", is a problem in the structure of the heart that is present at birth.[99] Signs and symptoms depend on the specific type of problem.[100] Symptoms can vary from none to life-threatening.[99] When present they may include rapid breathing, bluish skin, poor weight gain, and feeling tired.[101] It does not cause chest pain.[101] Most congenital heart problems do not occur with other diseases.[100] Complications that can result from heart defects include heart failure.[101]

The cause of a congenital heart defect is often unknown.[102] Certain cases may be due to infections during pregnancy such as rubella, use of certain medications or drugs such as alcohol or tobacco, parents being closely related, or poor nutritional status or obesity in the mother.[100][103] Having a parent with a congenital heart defect is also a risk factor.[104] A number of genetic conditions are associated with heart defects including Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Marfan syndrome.[100] Congenital heart defects are divided into two main groups: cyanotic heart defects and non-cyanotic heart defects, depending on whether the child has the potential to turn bluish in color.[100] The problems may involve the interior walls of the heart, the heart valves, or the large blood vessels that lead to and from the heart.[99]

Congenital heart defects are partly preventable through rubella vaccination, the adding of iodine to salt, and the adding of folic acid to certain food products.[100] Some defects do not need treatment.[99] Other may be effectively treated with catheter based procedures or heart surgery.[105] Occasionally a number of operations may be needed.[105] Occasionally heart transplantation is required.[105] With appropriate treatment outcomes, even with complex problems, are generally good.[99]

Heart defects are the most common birth defect.[100][106] In 2013 they were present in 34.3 million people globally.[106] They affect between 4 and 75 per 1,000 live births depending upon how they are diagnosed.[100][104] About 6 to 19 per 1,000 cause a moderate to severe degree of problems.[104] Congenital heart defects are the leading cause of birth defect-related deaths.[100] In 2013 they resulted in 323,000 deaths down from 366,000 deaths in 1990.[26]

Tetralogy of Fallot

editTetralogy of Fallot is the most common congenital heart disease arising in 1–3 cases per 1,000 births. The cause of this defect is a ventricular septal defect (VSD) and an overriding aorta. These two defects combined causes deoxygenated blood to bypass the lungs and going right back into the circulatory system. The modified Blalock-Taussig shunt is usually used to fix the circulation. This procedure is done by placing a graft between the subclavian artery and the ipsilateral pulmonary artery to restore the correct blood flow.

Pulmonary atresia

editPulmonary atresia happens in 7–8 per 100,000 births and is characterized by the aorta branching out of the right ventricle. This causes the deoxygenated blood to bypass the lungs and enter the circulatory system. Surgeries can fix this by redirecting the aorta and fixing the right ventricle and pulmonary artery connection.

There are two types of pulmonary atresia, classified by whether or not the baby also has a ventricular septal defect.[107][108]

- Pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum: This type of pulmonary atresia is associated with complete and intact septum between the ventricles.[108]

- Pulmonary atresia with a ventricular septal defect: This type of pulmonary atresia happens when a ventricular septal defect allows blood to flow into and out of the right ventricle.[108]

Double outlet right ventricle

editDouble outlet right ventricle (DORV) is when both great arteries, the pulmonary artery and the aorta, are connected to the right ventricle. There is usually a VSD in different particular places depending on the variations of DORV, typically 50% are subaortic and 30%. The surgeries that can be done to fix this defect can vary due to the different physiology and blood flow in the defected heart. One way it can be cured is by a VSD closure and placing conduits to restart the blood flow between the left ventricle and the aorta and between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. Another way is systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt in cases associated with pulmonary stenosis. Also, a balloon atrial septostomy can be done to relieve hypoxemia caused by DORV with the Taussig-Bing anomaly while surgical correction is awaited.[109]

Transposition of great arteries

editThere are two different types of transposition of the great arteries, Dextro-transposition of the great arteries and Levo-transposition of the great arteries, depending on where the chambers and vessels connect. Dextro-transposition happens in about 1 in 4,000 newborns and is when the right ventricle pumps blood into the aorta and deoxygenated blood enters the bloodstream. The temporary procedure is to create an atrial septal defect. A permanent fix is more complicated and involves redirecting the pulmonary return to the right atrium and the systemic return to the left atrium, which is known as the Senning procedure. The Rastelli procedure can also be done by rerouting the left ventricular outflow, dividing the pulmonary trunk, and placing a conduit in between the right ventricle and pulmonary trunk. Levo-transposition happens in about 1 in 13,000 newborns and is characterized by the left ventricle pumping blood into the lungs and the right ventricle pumping the blood into the aorta. This may not produce problems at the beginning, but will eventually due to the different pressures each ventricle uses to pump blood. Switching the left ventricle to be the systemic ventricle and the right ventricle to pump blood into the pulmonary artery can repair levo-transposition.[citation needed]

Persistent truncus arteriosus

editPersistent truncus arteriosus is when the truncus arteriosus fails to split into the aorta and pulmonary trunk. This occurs in about 1 in 11,000 live births and allows both oxygenated and deoxygenated blood into the body. The repair consists of a VSD closure and the Rastelli procedure.[110][111]

Ebstein anomaly

editEbstein's anomaly is characterized by a right atrium that is significantly enlarged and a heart that is shaped like a box. This is very rare and happens in less than 1% of congenital heart disease cases. The surgical repair varies depending on the severity of the disease.[112]

Pediatric cardiology is a sub-specialty of pediatrics. To become a pediatric cardiologist in the U.S., one must complete a three-year residency in pediatrics, followed by a three-year fellowship in pediatric cardiology. Per doximity, pediatric cardiologists make an average of $303,917 in the U.S.[5]

Diagnostic tests in cardiology

editDiagnostic tests in cardiology are the methods of identifying heart conditions associated with healthy vs. unhealthy, pathologic heart function. The starting point is obtaining a medical history, followed by Auscultation. Then blood tests, electrophysiological procedures, and cardiac imaging can be ordered for further analysis. Electrophysiological procedures include electrocardiogram, cardiac monitoring, cardiac stress testing, and the electrophysiology study.[citation needed]

Trials

editCardiology is known for randomized controlled trials that guide clinical treatment of cardiac diseases. While dozens are published every year, there are landmark trials that shift treatment significantly. Trials often have an acronym of the trial name, and this acronym is used to reference the trial and its results. Some of these landmark trials include:

- V-HeFT (1986) — use of vasodilators (hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate) in heart failure

- ISIS-2 (1988) — use of aspirin in myocardial infarction

- CASE I (1991) — use of antiarrhythmic agents after a heart attack increases mortality

- SOLVD (1991) — use of ACE inhibitors in heart failure

- 4S (1994) — statins reduce risk of heart disease

- CURE (1991) — use of dual antiplatelet therapy in NSTEMI

- MIRACLE (2002) — use of cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure

- SCD-HeFT (2005) — the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in heart failure

- RELY (2009), ROCKET-AF (2011), ARISTOTLE (2011) — use of DOACs in atrial fibrillation instead of warfarin

- PARADIGM-HF (2014) — use of angiotensin-neprilysin inhibitor in heart failure

- ISCHEMIA (2020) — medical therapy is as good as coronary stents in stable heart disease

- EMPEROR-Preserved (2021) — SGLT2 receptors in heart failure

Cardiology community

editAssociations

edit- American College of Cardiology

- American Heart Association

- European Society of Cardiology

- Heart Rhythm Society

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society

- Indian Heart Association

- National Heart Foundation of Australia

- Cardiology Society of India

Journals

edit- Acta Cardiologica

- American Journal of Cardiology

- Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia

- Current Research: Cardiology

- Cardiology in Review

- Circulation

- Circulation Research

- Clinical and Experimental Hypertension

- Clinical Cardiology

- EP – Europace

- European Heart Journal

- Heart

- Heart Rhythm

- International Journal of Cardiology

- Journal of the American College of Cardiology

- Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology

- Indian Heart Journal

Cardiologists

edit- Robert Atkins (1930–2003), known for the Atkins diet

- Christiaan Barnard (1922–2001), cardiac surgeon who performed the world's first human-to-human heart transplant operation

- Eugene Braunwald (born 1929), editor of Braunwald's Heart Disease and 1000+ publications

- Wallace Brigden (1916–2008), identified cardiomyopathy

- Manoj Durairaj (1971– ), cardiologist from Pune, India who received Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice

- Willem Einthoven (1860–1927), a physiologist who built the first practical ECG and won the 1924 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ("for the discovery of the mechanism of the electrocardiogram")

- Werner Forssmann (1904–1979), who infamously performed the first human catheterization on himself that led to him being let go from Berliner Charité Hospital, quitting cardiology as a speciality, and then winning the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ("for their discoveries concerning heart catheterization and pathological changes in the circulatory system")

- Andreas Gruentzig (1939–1985), first developed balloon angioplasty

- William Harvey (1578–1657), wrote Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus that first described the closed circulatory system and whom Forssmann described as founding cardiology in his Nobel lecture

- Murray S. Hoffman (1924–2018) As president of the Colorado Heart Association, he initiated one of the first jogging programs promoting cardiac health

- Max Holzmann (1899–1994), co-founder of the Swiss Society of Cardiology, president from 1952 to 1955

- Samuel A. Levine (1891–1966), recognized the sign known as Levine's sign as well as the current grading of the intensity of heart murmurs, known as the Levine scale

- Henry Joseph Llewellyn "Barney" Marriott (1917–2007), ECG interpretation and Practical Electrocardiography[113]

- Bernard Lown (1921–2021), original developer of the defibrillator

- Woldemar Mobitz (1889–1951), described and classified the two types of second-degree atrioventricular block often called "Mobitz Type I" and "Mobitz Type II"

- Jacqueline Noonan (1928–2020), discoverer of Noonan syndrome that is the top syndromic cause of congenital heart disease

- John Parkinson (1885–1976), known for Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

- Helen B. Taussig (1898–1986), founder of pediatric cardiology and extensively worked on blue baby syndrome

- Paul Dudley White (1886–1973), known for Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

- Fredrick Arthur Willius (1888–1972), founder of the cardiology department at the Mayo Clinic and an early pioneer of electrocardiography

- Louis Wolff (1898–1972), known for Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

- Karel Frederik Wenckebach (1864–1940), first described what is now called type I second-degree atrioventricular block in 1898

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Herper, Matthew (December 5, 2017). "27 Top Cardiologists, Picked By Big Data". Forbes. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ echoboards.org

- ^ apca.org/certifications-examinations/cbnc-and-cbcct/

- ^ "Specialties & Subspecialties". American Osteopathic Association. Archived from the original on 2015-08-13. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ a b Hamblin, James (January 27, 2015) What Doctors Make. theatlantic.com

- ^ a b Fauci, Anthony, et al. Harrison's Textbook of Medicine. New York: McGraw Hill, 2009.

- ^ Braunwald, Eugene, ed. Heart Disease, 6th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2011.

- ^ Cox JL, Churyla A, Malaisrie SC, Kruse J, Kislitsina ON, McCarthy PM (August 2022). "A history of collaboration between electrophysiologists and arrhythmia surgeons". J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 33 (8): 1966–1977. doi:10.1111/jce.15598. PMC 9543838. PMID 35695795.

- ^ DeMazumder D (December 2018). "The Path of an Early Career Physician and Scientist in Cardiac Electrophysiology". Circ Res. 123 (12): 1269–1271. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314016. PMC 6338224. PMID 30566044.

- ^ "Trends in Causes of Death among Older Persons in the United States" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Dodson JA (September 2016). "Geriatric Cardiology: An Emerging Discipline". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 32 (9): 1056–1064. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.03.019. PMC 5581937. PMID 27476988.

- ^ Golomb Beatrice A.; Dang Tram T.; Criqui Michael H. (2006-08-15). "Peripheral Arterial Disease". Circulation. 114 (7): 688–699. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593442. PMID 16908785. S2CID 5364055.

- ^ Yazdanyar, Ali; Newman, Anne B. (2010-11-01). "The Burden of Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly: Morbidity, Mortality, and Costs". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 25 (4): 563–vii. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.007. ISSN 0749-0690. PMC 2797320. PMID 19944261.

- ^ aseecho.org

- ^ King, Spencer B (March 1998). "The Development of Interventional Cardiology". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 31 (4): 64B–88B. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00558-5. ISSN 0735-1097.

- ^ "Cardiomyopathy". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ "Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ Murphy, Anne M. (2008-07-16). "The Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Collaboration". JAMA. 300 (3): 328–30. doi:10.1001/jama.300.3.328. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 18632547.

- ^ Pagidipati, Neha Jadeja; Gaziano, Thomas A. (2013). "Estimating Deaths From Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of Global Methodologies of Mortality Measurement". Circulation. 127 (6): 749–756. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.128413. ISSN 0009-7322. PMC 3712514. PMID 23401116.

- ^ Kashou, Anthony H.; Basit, Hajira; Chhabra, Lovely (2021), "Physiology, Sinoatrial Node", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29083608, retrieved 2021-04-22

- ^ Mebazaa, Alexandre; Gheorghiade, Mihai; Zannad, Faiez; Parrillo, Joseph E. (2009-12-24). Acute Heart Failure. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-84628-782-4.

- ^ According to the University of California, San Francisco, a comprehensive cardiac examination involves these three critical steps: inspection, palpation, and auscultation. This process helps in evaluating the heart's condition by first observing for visible signs, then feeling for abnormalities, and finally listening to the heart sounds.

- ^ Similarly, Chamberlain University outlines that the cardiac examination starts with inspection to identify any visual anomalies, followed by palpation to assess physical findings such as thrills or heaves, and concludes with auscultation to detect any abnormal heart sounds like murmurs or gallops.

- ^ Bhatia, Sujata K. (2010). Biomaterials for clinical applications (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 23. ISBN 9781441969200.

- ^ Wong, ND (May 2014). "Epidemiological studies of CHD and the evolution of preventive cardiology". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 11 (5): 276–89. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2014.26. PMID 24663092. S2CID 9327889.

- ^ a b c d GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ a b c "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Coronary Heart Disease?". 29 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)". 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Mehta, PK; Wei, J; Wenger, NK (16 October 2014). "Ischemic heart disease in women: A focus on risk factors". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 25 (2): 140–151. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2014.10.005. PMC 4336825. PMID 25453985.

- ^ Mendis, Shanthi; Puska, Pekka; Norrving, Bo (2011). Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control (PDF) (1st ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization. pp. 3–18. ISBN 9789241564373.

- ^ Charlson, FJ; Moran, AE; Freedman, G; Norman, RE; Stapelberg, NJ; Baxter, AJ; Vos, T; Whiteford, HA (26 November 2013). "The contribution of major depression to the global burden of ischemic heart disease: a comparative risk assessment". BMC Medicine. 11: 250. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-250. PMC 4222499. PMID 24274053.

- ^ "How Is Coronary Heart Disease Diagnosed?". 29 September 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b "How Can Coronary Heart Disease Be Prevented or Delayed?". Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Desai, CS; Blumenthal, RS; Greenland, P (April 2014). "Screening low-risk individuals for coronary artery disease". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 16 (4): 402. doi:10.1007/s11883-014-0402-8. PMID 24522859. S2CID 39392260.

- ^ Boden, WE; Franklin, B; Berra, K; Haskell, WL; Calfas, KJ; Zimmerman, FH; Wenger, NK (October 2014). "Exercise as a therapeutic intervention in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: an underfilled prescription". The American Journal of Medicine. 127 (10): 905–11. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.05.007. PMID 24844736.

- ^ a b c "How Is Coronary Heart Disease Treated?". 29 September 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Deb, S; Wijeysundera, HC; Ko, DT; Tsubota, H; Hill, S; Fremes, SE (20 November 2013). "Coronary artery bypass graft surgery vs percutaneous interventions in coronary revascularization: a systematic review". JAMA. 310 (19): 2086–95. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281718. PMID 24240936.

- ^ Rezende, PC; Scudeler, TL; da Costa, LM; Hueb, W (16 February 2015). "Conservative strategy for treatment of stable coronary artery disease". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 3 (2): 163–70. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i2.163. PMC 4317610. PMID 25685763.

- ^ Moran, AE; Forouzanfar, MH; Roth, GA; Mensah, GA; Ezzati, M; Murray, CJ; Naghavi, M (8 April 2014). "Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980 to 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study". Circulation. 129 (14): 1483–92. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.004042. PMC 4181359. PMID 24573352.

- ^ Moran, AE; Forouzanfar, MH; Roth, GA; Mensah, GA; Ezzati, M; Flaxman, A; Murray, CJ; Naghavi, M (8 April 2014). "The global burden of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study". Circulation. 129 (14): 1493–501. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.004046. PMC 4181601. PMID 24573351.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) (14 October 2011). "Prevalence of coronary heart disease—United States, 2006–2010". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 60 (40): 1377–81. PMID 21993341.

- ^ "Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Managing Cardiomyopathy" by Atrius Cardiac Care

- ^ a b c d "What Is Arrhythmia?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of an Arrhythmia?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Types of Arrhythmia". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Martin, C; Matthews, G; Huang, CL (2012). "Sudden cardiac death and Inherited channelopathy: the basic electrophysiology of the myocyte and myocardium in ion channel disease". Heart. 98 (7): 536–543. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300953. PMC 3308472. PMID 22422742.

- ^ "How Are Arrhythmias Diagnosed?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov/. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "How Are Arrhythmias Treated?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov/. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Who Is at Risk for an Arrhythmia?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov/. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Zoni-Berisso, M; Lercari, F; Carazza, T; Domenicucci, S (2014). "Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: European perspective". Clinical Epidemiology. 6: 213–20. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S47385. PMC 4064952. PMID 24966695.

- ^ a b Mehra, R (2007). "Global public health problem of sudden cardiac death". Journal of Electrocardiology. 40 (6 Suppl): S118–22. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2007.06.023. PMID 17993308.

- ^ a b c "What Is Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ a b Field, John M. (2009). The Textbook of Emergency Cardiovascular Care and CPR. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 11. ISBN 9780781788991.

- ^ a b "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ "What Causes Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ a b "How Can Death Due to Sudden Cardiac Arrest Be Prevented?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ "How Is Sudden Cardiac Arrest Treated?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Schenone AL, Cohen A, Patarroyo G, Harper L, Wang X, Shishehbor MH, Menon V, Duggal A (November 2016). "Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: A systematic review/meta-analysis exploring the impact of expanded criteria and targeted temperature". Resuscitation. 108: 102–110. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.238. PMID 27521472.

- ^ Kronick SL, Kurz MC, Lin S, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Billi JE, Cabanas JG, Cone DC, Diercks DB, Foster JJ, Meeks RA, Travers AH, Welsford M (November 2015). "Part 4: Systems of Care and Continuous Quality Improvement: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S397–413. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000258. PMID 26472992.

- ^ "Who Is at Risk for Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Adams, James G. (2012). Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials (Expert Consult – Online). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1771. ISBN 978-1455733941.

- ^ a b Naish, Jeannette; Court, Denise Syndercombe (2014). Medical sciences (2 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 562. ISBN 9780702052491.

- ^ a b c "High Blood Pressure Fact Sheet". CDC. February 19, 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Lackland, DT; Weber, MA (May 2015). "Global burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke: hypertension at the core". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 31 (5): 569–71. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.009. PMID 25795106.

- ^ Mendis, Shanthi; Puska, Pekka; Norrving, Bo (2011). Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control (PDF) (1st ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization. p. 38. ISBN 9789241564373.

- ^ a b c d e f Poulter, NR; Prabhakaran, D; Caulfield, M (22 August 2015). "Hypertension". Lancet. 386 (9995): 801–12. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61468-9. PMID 25832858. S2CID 208792897.

- ^ "High Blood Pressure". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 8 May 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Giuseppe, Mancia; Fagard, R; Narkiewicz, K; Redon, J; Zanchetti, A; Bohm, M; Christiaens, T; Cifkova, R; De Backer, G; Dominiczak, A; Galderisi, M; Grobbee, DE; Jaarsma, T; Kirchhof, P; Kjeldsen, SE; Laurent, S; Manolis, AJ; Nilsson, PM; Ruilope, LM; Schmieder, RE; Sirnes, PA; Sleight, P; Viigimaa, M; Waeber, B; Zannad, F; Redon, J; Dominiczak, A; Narkiewicz, K; Nilsson, PM; et al. (July 2013). "2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)" (PDF). European Heart Journal. 34 (28): 2159–219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. hdl:1854/LU-4127523. PMID 23771844.

- ^ James, PA.; Oparil, S.; Carter, BL.; Cushman, WC.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.; Handler, J.; Lackland, DT.; Lefevre, ML.; et al. (Dec 2013). "2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

- ^ Stergiou, George; Kollias, Anastasios; Parati, Gianfranco; O’Brien, Eoin (2018). "Office Blood Pressure Measurement". Hypertension. 71 (5). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 813–815. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.118.10850. ISSN 0194-911X. PMID 29531176. S2CID 3853179.

- ^ a b "How Is High Blood Pressure Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 10, 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Musini, Vijaya M; Tejani, Aaron M; Bassett, Ken; Puil, Lorri; Wright, James M (2019-06-05). Cochrane Hypertension Group (ed.). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults 60 years or older". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD000028. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub3. PMC 6550717. PMID 31167038.

- ^ Sundström, Johan; Arima, Hisatomi; Jackson, Rod; Turnbull, Fiona; Rahimi, Kazem; Chalmers, John; Woodward, Mark; Neal, Bruce (February 2015). "Effects of Blood Pressure Reduction in Mild Hypertension". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (3): 184–91. doi:10.7326/M14-0773. PMID 25531552.

- ^ Xie, X; Atkins, E; Lv, J; Bennett, A; Neal, B; Ninomiya, T; Woodward, M; MacMahon, S; Turnbull, F; Hillis, GS; Chalmers, J; Mant, J; Salam, A; Rahimi, K; Perkovic, V; Rodgers, A (30 January 2016). "Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 387 (10017): 435–43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. PMID 26559744. S2CID 36805676.

- ^ Diao, D; Wright, JM; Cundiff, DK; Gueyffier, F (Aug 15, 2012). "Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD006742. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006742.pub2. PMC 8985074. PMID 22895954.

- ^ Campbell, NR; Lackland, DT; Lisheng, L; Niebylski, ML; Nilsson, PM; Zhang, XH (March 2015). "Using the Global Burden of Disease study to assist development of nation-specific fact sheets to promote prevention and control of hypertension and reduction in dietary salt: a resource from the World Hypertension League". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 17 (3): 165–67. doi:10.1111/jch.12479. PMC 8031937. PMID 25644474. S2CID 206028313.

- ^ Carretero OA, Oparil S (January 2000). "Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology". Circulation. 101 (3): 329–35. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.3.329. PMID 10645931.

- ^ Oparil S, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA (November 2003). "Pathogenesis of hypertension". Ann. Intern. Med. 139 (9): 761–76. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00011. PMID 14597461. S2CID 32785528.

- ^ Hall, John E.; Guyton, Arthur C. (2006). Textbook of medical physiology. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- ^ "Hypertension: eMedicine Nephrology". Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ Messerli FH, Williams B, Ritz E (August 2007). "Essential hypertension". Lancet. 370 (9587): 591–603. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61299-9. PMID 17707755. S2CID 26414121.

- ^ "Secondary hypertension". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ a b White WB (May 2009). "Defining the problem of treating the patient with hypertension and arthritis pain". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (5 Suppl): S3–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.002. PMID 19393824.

- ^ Insull W (January 2009). "The pathology of atherosclerosis: plaque development and plaque responses to medical treatment". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (1 Suppl): S3–S14. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.10.013. PMID 19110086.

- ^ Liapis CD, Avgerinos ED, Kadoglou NP, Kakisis JD (May 2009). "What a vascular surgeon should know and do about atherosclerotic risk factors". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 49 (5): 1348–54. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2008.12.046. PMID 19394559.

- ^ Riccioni G (2009). "The effect of antihypertensive drugs on carotid intima media thickness: an up-to-date review". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (8): 988–96. doi:10.2174/092986709787581923. PMID 19275607. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Safar ME, Jankowski P (February 2009). "Central blood pressure and hypertension: role in cardiovascular risk assessment". Clinical Science. 116 (4): 273–82. doi:10.1042/CS20080072. PMID 19138169.

- ^ Werner CM, Böhm M (June 2008). "The therapeutic role of RAS blockade in chronic heart failure". Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 2 (3): 167–77. doi:10.1177/1753944708091777. PMID 19124420. S2CID 12972801.

- ^ Gaddam KK, Verma A, Thompson M, Amin R, Ventura H (May 2009). "Hypertension and cardiac failure in its various forms". The Medical Clinics of North America. 93 (3): 665–80. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.005. PMID 19427498. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Reisin E, Jack AV (May 2009). "Obesity and hypertension: mechanisms, cardio-renal consequences, and therapeutic approaches". The Medical Clinics of North America. 93 (3): 733–51. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.010. PMID 19427502. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Agabiti-Rosei E (September 2008). "From macro- to microcirculation: benefits in hypertension and diabetes". J Hypertens Suppl. 26 (3): S15–9. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000334602.71005.52. PMID 19363848.

- ^ Murphy BP, Stanton T, Dunn FG (May 2009). "Hypertension and myocardial ischemia". The Medical Clinics of North America. 93 (3): 681–95. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.003. PMID 19427499. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Tylicki L, Rutkowski B (February 2003). "[Hypertensive nephropathy: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment]". Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski (in Polish). 14 (80): 168–73. PMID 12728683.

- ^ Truong LD, Shen SS, Park MH, Krishnan B (February 2009). "Diagnosing nonneoplastic lesions in nephrectomy specimens". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 133 (2): 189–200. doi:10.5858/133.2.189. PMID 19195963. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Tracy RE, White S (February 2002). "A method for quantifying adrenocortical nodular hyperplasia at autopsy: some use of the method in illuminating hypertension and atherosclerosis". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 6 (1): 20–9. doi:10.1053/adpa.2002.30606. PMID 11842376.

- ^ Aronow WS (August 2008). "Hypertension and the older diabetic". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 24 (3): 489–501, vi–vii. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.03.001. PMID 18672184. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Gardner AW, Afaq A (2008). "Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 28 (6): 349–57. doi:10.1097/HCR.0b013e31818c3b96. PMC 2743684. PMID 19008688.

- ^ Novo S, Lunetta M, Evola S, Novo G (January 2009). "Role of ARBs in the blood hypertension therapy and prevention of cardiovascular events". Current Drug Targets. 10 (1): 20–5. doi:10.2174/138945009787122897. PMID 19149532. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d e "What Are Congenital Heart Defects?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. July 1, 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shanthi Mendis; Pekka Puska; Bo Norrving; World Health Organization (2011). Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control (PDF). World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization. pp. 3, 60. ISBN 978-92-4-156437-3.

- ^ a b c "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Congenital Heart Defects?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. July 1, 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "What Causes Congenital Heart Defects?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. July 1, 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Dean, SV; Lassi, ZS; Imam, AM; Bhutta, ZA (26 September 2014). "Preconception care: nutritional risks and interventions". Reproductive Health. 11 (Suppl 3): S3. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-s3-s3. PMC 4196560. PMID 25415364.

- ^ a b c Milunsky, Aubrey (2011). "1". Genetic Disorders and the Fetus: Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444358216.

- ^ a b c "How Are Congenital Heart Defects Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. July 1, 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ a b Vos, Theo; et al. (7 June 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ Ramaswamy P, Webber HS. "Ventricular Septal Defects: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology". Medscape. WebMD LLC. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Facts about Pulmonary Atresia: Types of Pulmonary Atresia". CDC. USA.gov. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Rao, P. Syamasundar (2019-04-04). "Management of Congenital Heart Disease: State of the Art—Part II—Cyanotic Heart Defects". Children. 6 (4): 54. doi:10.3390/children6040054. ISSN 2227-9067. PMC 6518252. PMID 30987364.

- ^ "Persistent Truncus Arteriosus – Pediatrics". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ^ Cleveland Clinic (September 17, 2021). "Truncus Arteriosus". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 2020-08-04.

- ^ Bhat, Venkatraman (2016). "Illustrated Imaging Essay on Congenital Heart Diseases: Multimodality Approach Part III: Cyanotic Heart Diseases and Complex Congenital Anomalies". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 10 (7): TE01–10. doi:10.7860/jcdr/2016/21443.8210. PMC 5020285. PMID 27630924.

- ^ Upshaw, Charles (18 April 2007). "Henry J. L. Marriott: Lucid Teacher of Electrocardiography". Clinical Cardiology. 30 (4): 207–8. doi:10.1002/clc.6. PMC 6652921. PMID 17443652.

Sources

edit- Braunwald, Eugene, ed. (2019). Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-46299-0.

- Ramrakha, Punit; Hill, Jonathan, eds. (2012). Oxford Handbook of Cardiology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964321-9.