Cyfeilliog or Cyfeiliog[1] (Old Welsh Cemelliauc,[2] probably d. 927) was a bishop in southeast Wales, but the location and extent of his diocese is uncertain. He is recorded in charters dating to the mid-880s, and in 914 he was captured by the Vikings and ransomed by Edward the Elder, King of the Anglo-Saxons, for 40 pounds of silver. Edward's asssistance is regarded by historians as evidence that he was overlord of the southeast Welsh kingdoms. Cyfeilliog is probably the author of a cryptogram (encrypted text) in the Juvencus Manuscript which would have required a knowledge of Latin and Greek. The twelfth-century Book of Llandaff records his death in 927, but some historians are sceptical as they think that this date is late for a bishop active in the 880s.

Political background

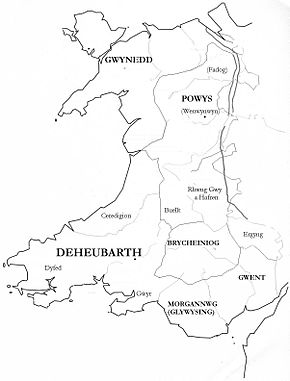

editIn the ninth century, southeast Wales was divided into three kingdoms, which were sometimes combined by more powerful kings. Gwent, north of the Severn Estuary, was south of Ergyng (now southwest Herefordshire) and east of Glywysing (now Glamorgan).[3] Mercia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom on the eastern Welsh border, traditionally claimed hegemony over most of Wales. In 873 the Vikings drove out King Burgred of Mercia and appointed Ceolwulf as a client king. Ceolwulf maintained Mercian efforts to control the Welsh, and in 878 he defeated and killed Rhodri Mawr, King of Gwynedd in north Wales, but Ceolwulf died or disappeared around 879 and was replaced by Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians. In 881, Rhodri's sons defeated Æthelred in battle, but he still continued to dominate the southeast Welsh kingdoms, and they sought the protection of King Alfred the Great of Wessex.[4] Alfred's Welsh biographer, Asser, wrote in 893:

- At that time, and for a considerable time before then, all the districts of right-hand [southern] Wales belonged to King Alfred, and still do...Hywel ap Rhys (the king of Glywysing) and Brochfael and Ffernfael (sons of Meurig and kings of Gwent), driven by the might and tyrannical behaviour of Ealdorman Æthelred and the Mercians, petitioned King Alfred of their own accord, in order to obtain lordship and protection from him in the face of their enemies.[5]

Ecclesiastical appointments

editCyfeilliog may have been an abbot before he became a bishop. He is included in a list of abbots of Llantwit said to have been in a "very decayed and rent" parchment discovered in about 1719, but as the source for the document was the forger Iolo Morganwg, it is uncertain whether it was genuine. The historian Patrick Sims-Williams comments that the fact that Cyfeilliog is not mentioned in any charter before he became a bishop "leaves open the possibility that he really is the Camelauc [Cyfeilliog] listed among the abbots of Llantwit, dubious though the source is".[6]

Cyfeilliog is first recorded in charters dating to the mid-880s. The earliest is probably a grant to him of two serfs and their progeny from King Hywel ap Rhys of Glywsing, who died in 886.[7] According to a Canterbury list of Professions of Obedience, Cyfeilliog was consecrated as a bishop by Æthelred, who was Archbishop of Canterbury between 870 and 888. Historians are uncertain of the validity of the list, but as southern Welsh kings accepted Alfred's overlordship in the 880s, acknowledgement of the primacy of Canterbury by bishops at this time would not be unlikely.[8] Three clerical witnesses to Cyfeilliog's charters also witnessed those of Bishop Nudd, and another three those of Bishop Cerennyr, probably because these bishops were Cyfeilliog's predecessors, and he inherited members of their episcopal households. Cerennyr was active over the whole of the southeast, suggesting that he had a superior status.[9] In a list of bishops in the twelfth-century Book of Llandaff Cyfeilliog is placed after Nudd.[10]

Diocese

editCyfeilliog is included in a list of bishops of Llandaff, covering the whole of southeast Wales between the River Wye and the River Towy, in the Book of Llandaff.[11] The designation was accepted by John Edward Lloyd in 1939 in his classic History of Wales,[12] but the early bishops in the list are rejected by later historians as an attempt to extend the history of the diocese back to an implausibly early date.[13] Cyfeilliog was bishop of a smaller area. Grants which Cyfeilliog received suggest that he was mainly active in Gwent.[11] All those which can be securely located are near Caerwent in Gwent, suggesting that he was probably based in the town.[14] He is named as a beneficiary in charters of the late ninth and early tenth centuries, but none of them relate to Glywysing, west of Gwent.[15]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle described Cyfeilliog as bishop of Archenfield,[16] which was the English name for Ergyng, north of Gwent.[17] In this period, Ergyng was Welsh in language and custom, but under English rule. Cyfeilliog's see probably covered Gwent and Ergyng. He may have been described by English chroniclers as bishop of Archenfield because he ministered to Welsh people there with the approval of the Bishop of Hereford, leading English writers to assume that this was Cyfeilliog's see.[11]

Charters

editCharters preserved in the Book of Landaff record nine grants of land to Cyfeilliog from Hywel ap Rhys and his son Arthfael, and from Brochfael ap Meurig, King of Gwent.[18] King Hywel gave Cyfeilliog two slaves and their progeny in about 885 for the souls of his wife, sons and daughters.[19] A witness called Asser attested this charter immediately after Cyfeilliog, and the Asser who was biographer of Alfred the Great spent a year in Caerwent at this time; it is possible that he was temporarily attached to Cyfeilliog and attested the charter in a position of honour.[20] Around 890, King Arthfael granted Villa Caer Birran, at Treberran, Pencoyd, with four modii[a] (about 160 acres (60 hectares)) of land to Cyfeilliog.[22]

Cyfeilliog had several legal disputes with King Brochfael. In about 905, there was a disagreement between their households. Cyfeilliog was awarded an "insult price" "in puro auro" (in pure gold) of the worth of his face, lengthwise and breadthwise. The charter refers to his value in a fixed scale in accordance with his status, under the legal concept of wynepwerth (honour, literally face-worth). Brochfael was unable to pay in gold and paid with six modii (about 240 acres (100 hectares)) of land at Llanfihangel instead.[23] Brochfael gave a church in Monmouth with three modii of land to his daughter, described as "a holy virgin". In around 910, there was a dispute between Cyfeilliog and Brochfael over the church and its land, and judgement was again given in Cyfeilliog's favour and endorsed by Brochfael.[24]

Brochfael donated property to Cyfeilliog in several charters. In one he gave land with weirs on the Severn and the Afon Meurig, a tributary of the Teifi, together with rights of shipwreck, and in another charter two churches, with six modii of land and landing rights for ships at the mouth of the Troggy.[25]

Capture by the Vikings

editIn 914 Cyfeilliog was captured by the Vikings, and the event was recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- In this year a great naval force came over here from the south from Brittany, and two earls, Ohter and Hroald, with them. And they went west round the coast so that they arrived at the Severn Estuary and ravaged in Wales everywhere along the coast where it suited them. And they captured Cyfeilliog, bishop of Archenfield, and took him with them to the ships; and then King Edward ransomed him for 40 pounds [of silver].[26][b]

The payment of Cyfeilliog's ransom, described by Charles-Edwards as "a princely sum", by Alfred's son and successor Edward the Elder is regarded by historians as evidence that he maintained his father's lordship over southeast Wales.[28]

Cryptogram

editA cryptogram (encrypted text) in the Juvencus Manuscript, which was written in Wales in the second half of the ninth century, praises a priest called Cemelliauc [Cyfeilliog]. Such cryptograms usually contained the names of their authors, and this one was probably about this Cyfeilliog as his name was uncommon and he is only known person with that name who was active when the Juvencus Manuscript was being written.[29] The cryptogram is in Latin, with each letter being the Greek for the number of the letter in the Latin alphabet. There are no errors in Greek in the cryptogram, and this would have been very difficult to achieve unless the writer knew the language, which was an unusual accomplishment in the period.[30] The cryptogram is described by the scholar Helen McKee as "charmingly boastful", and it reads in translation, with some words missing due to deterioration of the manuscript at the edge of the page:

- Cemelliauc the learned priest

- [ ] this without any trouble

- To God, brothers, constantly,

- Pray for me [ ].[31]

Death

editCyfeilliog died in 927 according to the Book of Llandaff.[32] The date is accepted by Charles-Edwards,[33] but Sims-Williams and Wendy Davies are sceptical because they regard the date as late for someone consecrated by Archbishop Æthelred, who died in 888.[34] According to the Book of Llandaff, Cyfeilliog was succeeded by Libiau[10] (also spelled Llibio and Llifio[35]), but the Canterbury consecration list says that Libiau was also consecrated by Æthelred, and he may have had a different see from Cyfeilliog.[36] Most bishops in the eighth and ninth centuries appear to have been active in both Gwent and Ergyng, but Cyfeilliog's successors seem to have only ministered in Gwent. Bishops of Hereford may have taken over in Ergyng.[37]

Notes

edit- ^ A modius was equivalent to about 40 acres (16 ha).[21]

- ^ The thirteenth-century chronicler John of Worcester wrote that Cyfeilliog was captured in Archenfield, but historians prefer the wording in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that Archenfield was the location of his diocese.[27]

References

edit- ^ Bartrum 1993, p. 161; Lloyd 1939, p. 332.

- ^ McKee 2000b, p. 27.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 425–426, 484–493.

- ^ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 53, 96, 262-263 n. 183.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, pp. 61–66, 171.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 171; Davies 1978, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Davies 1979, p. 78; Sims-Williams 2019, pp. 23–25, 171.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 595–596.

- ^ a b Bartrum 1993, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 594.

- ^ Lloyd 1939, p. 332 and n. 45.

- ^ Bartrum 1993, p. 161; Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 594.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 172.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2004; Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 245, 594.

- ^ Whitelock 1979, p. 212.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2004; Richards 1969, p. 66.

- ^ Lloyd 1959; Davies 1978, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Davies 1979, pp. 123–124; Sims-Williams 2019, p. 171; Evans & Rhys 1893, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 52, 94, 213, 220; Evans & Rhys 1893, p. 236; Sims-Williams 2019, p. 171–172.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 33.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 184; Bannister 1916, p. 187.

- ^ Evans & Rhys 1893, pp. 233–234; Davies 1979, pp. 123; Davies 1978, pp. 60, 110, 183; Sims-Williams 2019, p. 115.

- ^ Davies 1978, p. 182; Davies 1979, p. 122.

- ^ Davies 1979, p. 123.

- ^ Whitelock 1979, p. 212; Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 506.

- ^ Darlington & McGurk 1995, pp. 370–371; Sims-Williams 2019, p. 25.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 506.

- ^ McKee 2000b, pp. 27–28; McKee 2000a, p. 4.

- ^ McKee 2000b, p. 27; Lapidge 2014, p. 260.

- ^ McKee 2000a, pp. 20–21; McKee 2000b, p. 27.

- ^ Evans & Rhys 1893, p. 237.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2004.

- ^ Davies 1979, p. 78; Sims-Williams 2019, p. 172.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 68; Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 595.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 24 n. 6, 68-69.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2019, p. 176; Davies 1978, p. 154.

Bibliography

edit- Bannister, Arthur (1916). The Place-names of Herefordshire: Their origin and development. Cambridge, UK: J. Clay. OCLC 252303893.

- Bartrum, Peter (1993). A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A. D 1000. Aberystwyth, UK: The National Library of Wales. ISBN 978-0-907158-73-8.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2004). "Cyfeilliog (d. 927)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5420. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Darlington, Reginald; McGurk, Patrick, eds. (1995). The Chronicle of John of Worcester (in Latin and English). Vol. 2. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822261-3.

- Davies, Wendy (1978). An Early Welsh Microcosm: Studies in the Llandaff Charters. London, UK: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901050-33-5.

- Davies, Wendy (1979). The Llandaff Charters. Aberystwyth, UK: National Library of Wales. ISBN 978-0-901833-88-4.

- Evans, John Gwenoguryn; Rhys, John, eds. (1893). The Text of the Book of Llan Dâv. Oxford, UK: J. Gwenoguryn Evans. OCLC 632938065.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources. London, UK: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Lapidge, Michael (2014). "Israel the Grammarian". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 260–61. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1939). A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). London, UK: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 799460645.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1959). "Cyfeiliog". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Cardiff, UK: The National Library of Wales.

- McKee, Helen (Summer 2000a). "Scribes and Glosses from Dark Age Wales: The Cambridge Juvencus Manuscript". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies (39): 1–22. ISSN 1353-0089.

- McKee, Helen (2000b). The Cambridge Juvencus Manuscript Glossed in Latin, Old Welsh, and Old Irish: Text and Commentary. Aberystwyth, UK: CMCS Publications. ISBN 978-0-9527478-2-6.

- Richards, Melville (1969). Welsh Administrative and Territorial Units. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-900-76808-8.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick (2019). The Book of Llandaf as a Historical Source. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-418-5.

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1979) [1st edition 1955]. English Historical Documents, Volume 1, c. 500–1042 (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14366-0.