George Cadbury (19 September 1839 – 24 October 1922) was an English Quaker businessman and social reformer who expanded his father's Cadbury's cocoa and chocolate company in Britain.

George Cadbury | |

|---|---|

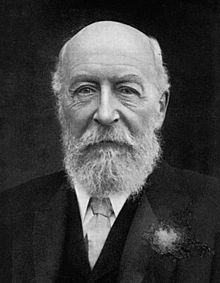

George Cadbury, aged 78 [1917] | |

| Born | 19 September 1839 |

| Died | 24 October 1922 (aged 83) |

| Occupation | Director of Cadbury's |

| Years active | 1861−1918 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 11, including: Edward Cadbury George Cadbury Jr Egbert Cadbury Marion Greeves |

| Father | John Cadbury (1801-1889) |

| Relatives | Richard Cadbury (brother) |

Background

editGeorge Cadbury was the son of John Cadbury, a tea and coffee dealer, and his wife Candia.[1]

The Cadburys were members of the Society of Friends or Quakers.

He worked at a school for adults on Sundays with no pay, despite only going to the school himself till he was fifteen.[2] At sixteen, he was apprenticed to Joseph Rowntree, in York, to learn the grocery trade.

Cadbury Brothers Limited

editWhen his family firm was in trouble, due to his father’s declining health after his mother’s death from tuberculosis in 1855, he moved back to Birmingham without having completed his apprenticeship. His older brother Richard was already working in their father’s business, and the two brothers took over the chocolate producer Cadbury Brothers in 1861.[3]

In 1878, they acquired 14 acres (57,000 m2) of land in open country, four miles (6 km) south-west of Birmingham, where they opened a new factory in 1879. When Cadbury Brothers was incorporated as a limited company on 16 June 1899, George and Richard owned 100% of the ordinary shares in their business.[4]

Their father had previously been working on a blend of cocoa and lichen that he had hoped had medicinal properties. The brothers continued the work and launched the product as “Icelandic Moss”. Although it was not the success that they had hoped for, they worked long hours and lived a very frugal lifestyle to keep the firm from insolvency with help from the £4000 that had been left to them by their mother. When George heard about a Dutch chocolatier, Coenraad van Houten, who had devised a method of extracting most of the unpalatable fat from cocoa, which made it a more appealing drink; he went to Holland to see Van Houten although he didn’t speak Dutch. He returned triumphant with a defatting machine. The machine proved to be a success and Cadbury’s launched their “Absolutely Pure Therefore Best” cocoa essence. It saved the company and enabled it to grow into a large and successful enterprise with a reputation for quality products and for treating its employees well.[3]

The Cadbury brothers were concerned with the quality of life of their employees and provided an alternative to city life. As more land was acquired and the brothers moved the factory to a new country location, they decided to build a factory town (designed by architect William Alexander Harvey), which was not exclusive to the employees of the factory. This village became known as Bournville after the nearby river and French word for "town". The houses were never privately owned, and their value stayed low and affordable. Bournville was a marked change from the poor living conditions of the urban environment. Here, families had houses with yards, gardens, and fresh air. By 1900, when Cadbury renounced his proprietorship of the estate and set up the Bournville Village Trust, there were 313 houses for various social classes; by 1960 the trust held 1,000 acres with 3,500 houses.[5] To the present, the town offers affordable housing.

The brothers cared for their employees; they both believed in workers’s social rights and hence they installed canteens and sport grounds. Nineteen years after Richard died, George opened a works committee for each gender which discussed proposals for improving the firm. He also pressed ahead with other ideas, like an annuity, a deposit account and education facilities for every employee.

Philanthropy

editHe rented 'Woodbrooke' – a Georgian style mansion built by Josiah Mason, which he eventually bought in 1881. In 1903, he founded a Quaker higher educational institution for social-service oriented education – an institution that still functions as the Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre.[6] In the early 20th century, he and John Wilhelm Rowntree established a Quaker study centre in the building,[7] and it remains the only such centre in Europe today, offering short educational courses on spiritual and social matters to Quakers and others.

In 1901, disgusted by the imperialistic policy of the Unionist Government dominated by Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, and opposed to the Boer War, George Cadbury bought the Daily News (afterward the News Chronicle) and used the paper to campaign for old age pensions and against the war and sweatshop labour.[8] Cadbury was actively involved in politics and supported William Gladstone. Dismayed at how the Liberals took the country into the First World War (1914-1918), George switched his allegiance to the Independent Labour Party who were anti war. [1]

In 1907, George Cadbury bought Selly Manor, an old Tudor house menaced by destruction in the surroundings of Birmingham. He decided to rescue, preserve and move it to Bournville. This was completed in 1916 by architect William Alexander Harvey.[9] Selly Manor is now a museum.

George Cadbury was one of the prime movers in setting up The Birmingham Civic Society in 1918. Cadbury donated the Lickey Hills Country Park to the people of Birmingham. He also donated a large house in Northfield to the Birmingham Cripples Union that was used as a hospital from 1909. It is now called the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital.[10]

He died at home, Northfield Manor House, on 24 October 1922, aged 83 of natural causes.[1]

Family life

editGeorge Cadbury married twice. In London, Middlesex, on 14 March 1872 he married Mary Tylor (born March 1849 at Stamford Hill, London; died June 1887 at Newton Abbot in Devon), daughter of Quaker author Charles Tylor and wife Gulielma Maria Sparkes.[11] She was the mother of George Jr, Mary Isabel, Edward, Henry, and Eleanor Cadbury.

In Peckham Rye, Southwark, London, on 19 June 1888 he married Elizabeth Mary Taylor. They had six children together: Laurence John, George Norman, Elsie Dorothea, Egbert, Marion Janet, and Ursula.

Legacy

editThe George Cadbury Carillon School was opened in 2006 and is the only carillon school in the United Kingdom.[12]

George Cadbury has a miniature locomotive named after him, originally owned by the husband of his daughter Elsie Dorothea, Geoffrey Hoyland.[13]

Biography

edit- Walter Stranz: George Cadbury: An Illustrated Life of George Cadbury, 1839-1922 (Shire Publications, Aylesbury, 1973) ISBN 0-85263-236-3

- Claus Bernet (2008). "George Cadbury". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 29. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 257–261. ISBN 978-3-88309-452-6.

- A. G. Gardiner (1923) George Cadbury Cassell and Company Limited ASIN B0006D79IW

- Andrew Reekes Two Titans, One City: Joseph Chamberlain & George Cadbury West Midlands History (28 Feb. 2017) ISBN 9781905036349

References

edit- ^ a b c "George Cadbury". Britain unlimited.

- ^ The Garden City: The Official Organ of the Garden City Association. Garden City Association.

- ^ a b "George Cadbury". Quakers in the world.

- ^ Franks, Julian; Mayer, Colin; Rossi, Stefano (2005). "Spending Less Time with the Family: The Decline of Family Ownership in the United Kingdom". In Morck, Randall K. (ed.). A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Mergers. University of Chicago Press. p. 600. ISBN 0-226-53680-7.

- ^ L. Nolen, Jeannette (15 September 2023). "George Cadbury". Britannica.

- ^ "Woodbrooke | Quaker Learning & Research Organisation". 3 April 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Thomas C. Kennedy (2001). British Quakerism, 1860–1920: the transformation of a religious community. Oxford University Press. pp. 177–78. ISBN 0-19-827035-6.

- ^ Kevin Grant (2005). A civilised savagery: Britain and the new slaveries in Africa, 1884–1926. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 0-415-94901-7.

- ^ "Selly Manor's History". Selly Manor Museum. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Royal Orthopaedic Hospital". Rossbret Institutions Website. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ David J. Jeremy (1990). Capitalists and Christians: business leaders and the churches in Britain, 1900–1960. Clarendon Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-19-820121-4.

- ^ "Carillon Summer series". Indiana State University. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ "Downs Light Railway Trust - History". Downs Light Railway Trust. 2022.

- "Burke's Peerage and Baronetage"