Alan Louis Charles Bullock, Baron Bullock, FBA (13 December 1914 – 2 February 2004) was a British historian. He is best known for his book Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952), the first comprehensive biography of Adolf Hitler, which influenced many other Hitler biographies.

The Lord Bullock | |

|---|---|

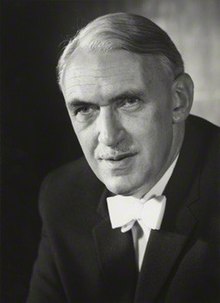

Bullock in 1969 | |

| Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University | |

| In office 1969–1973 | |

| Preceded by | Kenneth Turpin |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Habakkuk |

| 1st Master of St Catherine's College, Oxford | |

| In office 1962–1981 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 December 1914 Trowbridge, Wiltshire, England |

| Died | 2 February 2004 (aged 89) Oxford, England |

| Spouse | Hilda Yates Handy ("Nibby") married 1 June 1940 |

| Children | Nicholas; Adrian; Clair; Rachel; Matthew. |

| Parent(s) | Frank Allen Bullock, Edith (Brand) Bullock |

| Alma mater | Wadham College, Oxford |

Early life and career

editBullock was born in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, England,[1] the only child of Edith (neé Brand) and Reverend Frank Allen Bullock,[2] the latter a gardener turned Unitarian preacher.[3] Alan was educated at Bradford Grammar School and Wadham College, Oxford, where he studied classics and modern history.[4] After graduating in 1938, he worked as a research assistant for Winston Churchill, who was then writing his History of the English-Speaking Peoples.[5] Bullock was a Harmsworth Senior Scholar at Merton College, Oxford, from 1938 to 1940.[6] During World War II, he worked for the European Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). After the war, he returned to Oxford as a history fellow at New College.[7]

Bullock was the censor of St Catherine's Society (1952–1962) and then founding master of St Catherine's College, Oxford (1962–1981),[8][9] a college for undergraduates and graduates, divided between students of the sciences and the arts. He was credited with massive fundraising efforts to develop the college. Later, he was the first full-time Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University (1969–1973).[1][10][11]

Bullock served as chairman of the National Advisory Committee on the Training and Supply of Teachers (1963–1965), the Schools' Council (1966–1969), the Committee of Inquiry into Reading and the Use of English (1972–1974), and the Committee of Inquiry on Industrial Democracy (1976–1977).[1]

Bullock became widely known to the general public when he appeared on the informational BBC radio program The Brains Trust.[1]

Hitler: A Study in Tyranny

editIn 1952, Bullock published Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, the first comprehensive biography of Adolf Hitler, which utilized the recently available transcripts of the Nuremberg Trials as well as traditional resources such as letters, diaries, speeches and memoirs. The biography dominated Hitler scholarship for many years and portrayed the German dictator as an opportunistic Machtpolitiker ("power politician"). In Bullock's opinion, Hitler was a "mountebank" and adventurer devoid of scruples or beliefs, whose actions throughout his career were motivated only by a lust for power. Early in the book, Bullock writes the following about Hitler's formative pre-World War I years in Vienna when he was alone and struggling:

Such were the principles which Hitler drew from his years in Vienna. Hitler never trusted anyone; he never committed himself to anyone, never admitted any loyalty. His lack of scruple later took by surprise even those who prided themselves on their unscrupulousness. He learned to lie with conviction and dissemble with candour.[12]

Bullock's interpretation of Hitler led to a debate in the 1950s with Hugh Trevor-Roper, who argued that Hitler did possess beliefs, albeit repulsive ones, and that his actions were motivated by them. Bullock was somewhat swayed by this debate and partially modified his assessment of Hitler. In his later writings, such as Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (1991), Bullock depicted the dictator as more of an ideologue who had pursued the ideas expressed in Mein Kampf and elsewhere despite their consequences.[3]

His work on the Hitler biography prompted Bullock to examine the role of the individual in history. Taking note of the shift in interest among professional historians towards social history, he agreed that deep long-term social forces are generally the decisive historical factor. However, he believed there are times in which the "Great Man" is decisive. For instance, he wrote that during revolutionary circumstances, "It is possible for an individual to exert a powerful even a decisive influence on the way events develop and the policies that are followed."[13]

Hitler: A Study in Tyranny has remained an important and relevant work. In 1991, John Campbell said of it: "Although written so soon after the end of the war and despite a steady flow of fresh evidence and reinterpretation, it has not been surpassed in nearly 40 years: an astonishing achievement."[14] In the obituary for Bullock in The Guardian, Rebecca Smithers stated that "Bullock's famous maxim 'Hitler was jobbed into power by backstairs intrigue' has stood the test of time."[15]

Other works

editBullock's other works included The Liberal Tradition: From Fox to Keynes (1956) (co-edited with Maurice Shock), The Forming of the Nation (1969); Is History Becoming a Social Science? The Case of Contemporary History (1977); Has History a Future? (1977); The Humanist Tradition in the West (1985); Meeting Teachers' Management Needs (1988); Great Lives of the Twentieth Century (1989); and The Life and Times of Ernest Bevin (1960). The last was a three-volume biography of British Labour Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin.[16] Bullock was also co-editor (along with Oliver Stallybrass) of The Harper Dictionary of Modern Thought (1977), a project that Bullock suggested to his Harper & Row publisher when he found he could not define the word "hermeneutics".[17]

In the mid-1970s, Bullock used his committee skills to produce a report which proved influential in the classroom, A Language for Life (1975).[7][18] It offered recommendations for improving English teaching in the UK. Bullock later chaired the committee of inquiry on industrial democracy commissioned in December 1975 by the second Labour government of Harold Wilson. The committee's report, which was also known as the Bullock Report, published in 1977, recommended workers' control in large companies with employees having a right to hold representative worker directorships.

Bullock occasionally appeared on television as a political pundit, for example, during the BBC coverage of the 1959 British general election.[19]

Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives

editLate in his life, Bullock published Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (1991) – a massive and consequential book which he characterized in the Introduction as "essentially a political biography, set against the background of the times in which they lived."[20] He showed how the careers of Hitler and Joseph Stalin fed off each other to some extent. Bullock argued that Stalin's ability to consolidate power in his home country and to not (unlike Hitler) over-extend himself, enabled him to retain power longer than Hitler. Bullock's book was awarded the 1992 Wolfson History Prize.

Ronald Spector, writing in The Washington Post, praised Bullock for describing the development of Nazism and Soviet Communism without relying on abstract generalization or irrelevant detail: "The writing is invariably interesting and informed and there are new insights and cogent analysis in every chapter."[4] Amikam Nachmani noted how Hitler and Stalin "come out as two blood-thirsty, pathologically evil, sanguine tyrants, who are sure of the presence of determinism, hence having unshakeable beliefs that Destiny assigned on them historical missions—the one to pursue a social industrialized revolution in the Soviet Union, the other to turn Germany into a global empire."[21]

Honours

editBullock was decorated with the award of the Chevalier, Legion of Honour in 1970, and knighted in 1972, becoming Sir Alan Bullock and on 30 January 1976 he was created a life peer as Baron Bullock, of Leafield in the County of Oxfordshire.[22] His writings always appeared under the name "Alan Bullock".

In May 1976, Bullock was awarded an honorary degree from the Open University as Doctor of the university.[23]

Death

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e "Alan Louis Charles Bullock biography – British historian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ Dickson, Peter. "Alan Louis Charles Bullock, 1914–2004" (PDF). Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b Saxon, Wolfgang (5 February 2004). "Alan Bullock, 89, a British Historian Who Wrote a Life of Hitler". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Adam (4 February 2004). "Alan Bullock, Historian of Hitler and Stalin, Dies". The Washington Post.

- ^ Lough, David (2015). No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money. New York: Picador. p. 285.

- ^ Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 289.

- ^ a b Frankland, Mark (3 February 2004). "Lord Bullock of Leafield". The Guardian.

- ^ Europa Publications (2003). The International Who's Who: 2004. Psychology Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-85743-217-6.

- ^ "St Catherine's Society". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Previous Vice-Chancellors | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Previous Vice-Chancellors". University of Oxford, UK. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Bullock, Alan (1958). Hitler, A Study in Tyranny. New York: Bantam Books. p. 10. LCCN 58-11780.

- ^ Bullock, Alan, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (1991), p. 976.

- ^ John Campbell, 'The lesson of two evils', The Times Saturday Review (22 June 1991), p. 21.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (3 February 2004). "Bullock, visionary historian, dies aged 89". The Guardian.

- ^ Keith G. Robbins (1996). A Bibliography of British History: 1914–1989. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-822496-9.

- ^ Gentleman, Amelia (22 July 1999). "Hermeneutic defence against dumbing down". The Guardian.

- ^ R. C. S. Trahair (1994). From Aristotelian to Reaganomics: A Dictionary of Eponyms With Biographies in the Social Sciences. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-313-27961-4.

- ^ BBC 1959 General Election Coverage Part 3 on YouTube

- ^ Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (London: HarperCollins, 1991; New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991; second revised edition, New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

- ^ Nachmani, p. 783.

- ^ "State Intelligence". The London Gazette. No. 46815. 3 February 1976. p. 1679.

- ^ "Honorary Graduate Cumulative List" (PDF). Open University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

Further reading

edit- Caston, Geoffrey. "Alan Bullock: historian, social democrat and chairman." Oxford Review of Education 32.1 (2006): 87–103.

- Nachmani, Amikam. "Alan Bullock, 1914–2004: 'I Only Write Enormous Books'." Diplomacy and Statecraft 16.4 (2005): 779–786 online.

- Rosenbaum, Ron, Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil, New York: Random House, 1998. ISBN 0-679-43151-9.

Primary sources

edit- Bullock, Alan. Hitler, A Study in Tyranny (Abridged edition 1971)

- Bullock, Alan. Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (1991)