Bourke is a town in the north-west of New South Wales, Australia. The administrative centre and largest town in Bourke Shire, Bourke is approximately 800 kilometres (500 mi) north-west of the state capital, Sydney, on the south bank of the Darling River. it is also situated:

- 137 kilometres south of Barringun and the Queensland – New South Wales Border

- 256 kilometres (159 mi) south of Cunnamulla

- 454 kilometres (282 mi) south of Charleville

| Bourke New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

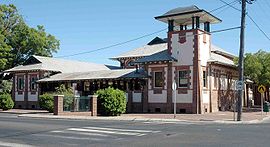

Court house, former maritime court | |||||||||||||||

| Population | 1,824 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2840 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 106 m (348 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Bourke Shire | ||||||||||||||

| County | Cowper County | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Barwon | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Parkes | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

History edit

The location of the current township of Bourke is on a bend in the Darling River on the traditional country of the Ngemba people. Archaeological sites indicate Aboriginal occupancy of the region dating back thousands of years.[2]

The first British explorer to explore the river was Charles Sturt in 1828 who named it after Sir Ralph Darling, Governor of New South Wales. Having struck the region during an intense drought and a low river, Sturt dismissed the area as largely uninhabitable and short of any features necessary for establishing reliable industry on the land.[3]

Further exploration of the area did not occur until 1835 when the colonial surveyor Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted an expedition. Following tensions with the local people Mitchell built a small stockade to protect his men and named it Fort Bourke after then Governor Sir Richard Bourke. British pastoral settlement failed to occur for many years in the vicinity due to the large distances from the colonised areas and the strong resistance from the local Aboriginal population.[4]

It wasn't until 1859 when British colonists were able to gain a foothold along the Upper Darling, with the arrival of paddle steamers making river transportation and trade to the southern settlements seasonally viable.[4] The first paddle steamer to reach Fort Bourke was the Genesis in February 1859, skippered by Captain William Randell.[5]

The first British pastoralist to appropriate land around Fort Bourke was Edward J Spence in late 1858, but it was Vincent James Dowling with his head stockman, John E Kelly, who successfully established the Fort Bourke cattle station and homestead in 1859. Dowling clashed with the resident Aboriginal population, receiving a spear through his hat and his horse being wounded by a boomerang. However, he was able to come to terms with the Indigenous people, who became a cheap source of labour for his run.[6]

The immediate area around Fort Bourke where Mitchell had originally built his little stockade was deemed too flood prone for a township, so an elevated site on the east bank of the river around 10km north of the fort was chosen for closer settlement. This site was called by the Indigenous people Whertiemurtie and by the colonists 18 Mile Point. In 1862 the township of Bourke was officially surveyed and laid out at this locality.[7][8][9]

As the pastoralist industry expanded around Bourke, the town rapidly grew into a busy river port, with paddle steamers shipping large quantities of stock and wool south to Echuca, from where the railway extension allowed further transportation to Melbourne.[9]

Road infrastructure improved with the opening on 4 May 1883 of the North Bourke Bridge, designed by J.H. Daniels and modified in 1895 and 1903 by E.M. de Burgh. Its construction was begun by David Baillie and completed by McCulloch and Company. The 1895 modifications led to improved designs for subsequent lift-span bridges. The bridge is the oldest moveable-span bridge in Australia and is the sole survivor of its type in New South Wales. It served for 114 years before being bypassed in 1997 when a new bridge carrying the Mitchell Highway was opened just downstream.[10]

By 1885 Bourke was made accessible by rail and reliance on the river trade to the south was quickly replaced by the more direct rail access to Sydney.[9] Like many outback Australian townships, Bourke also utilised camels for overland transport, and the area supported a large Afghan community that had been imported to drive the teams of camels. A small Afghan mosque that dates back to the 1900s can be found within Bourke cemetery.

As trade moved away from river transport routes, Bourke's hold on the inland trade industry began to relax. Whilst no longer considered a trade centre, Bourke serves instead as a key service centre for the state's north western regions. In this semi-arid outback landscape, sheep farming along with some small irrigated cotton crops comprise the primary industry in the area today.[11]

Bourke's traditional landholders endured a similar fate to Indigenous people across Australia. Dispossessed of their traditional country and in occasional conflict with white settlers, they battled a loss of land and culture and were hit hard by European disease. While the population of the local Ngemba and Barkindji people around the town of Bourke had dwindled by the late 19th century, many continued to live a traditional lifestyle in the region. Others found employment on local stations working with stock and found their skill as trackers in high demand.

A large influx of displaced Aboriginal peoples from other areas in the 1940s saw Bourke's indigenous community grow and led to the establishment of a reserve in 1946 by the Aborigines Protection Board. The majority of indigenous settlers were Wangkumara people from the Tibooburra region.[12]

In 1962 in Perth, local high jumper Percy Hobson became the first person of Aboriginal descent to win a Commonwealth Games gold medal for Australia. The 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) tall Hobson jumped 13 in (33 cm) above his height to win the event with a Games record leap of 6 ft 11 in (2.11 m). Hobson was celebrated on his return to Bourke and greeted by a brass band playing "Hail the Conquering Hero".[13] A park and illustrated water tower now contribute to his memory.

Heritage listings edit

Bourke has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- 3–7 Meek Street: St Ignatius Roman Catholic Church and Convent[14]

- 45 Mitchell Street: Towers Drug Company Building[15]

- 47 Oxley Street: Bourke Post Office[16]

- Richard Street: Bourke Court House[17]

- 5 Richard Street: Ardsilla[18]

- 17 Sturt Street: Old London Bank Building[19]

- The North Bourke Bridge, opened in 1883, is on the Engineering Heritage Register.[20]

Population edit

In 2016, there were 1,824 people in Bourke.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 38.0% of the population.

- 78.1% of people were born in Australia and 80.2% spoke only English at home.

- The most popular (40.2%) religion was Catholicism.[1]

In Bourke today, there are 21 recognised indigenous language groups, including Ngemba, Barkindji, Wangkumara and Muruwari.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 1,430 | — |

| 1933 | 1,778 | +24.3% |

| 1947 | 2,025 | +13.9% |

| 1954 | 2,642 | +30.5% |

| 1961 | 3,001 | +13.6% |

| 1966 | 3,300 | +10.0% |

| 1971 | 3,622 | +9.8% |

| 1976 | 3,534 | −2.4% |

| 1981 | 3,326 | −5.9% |

| 1986 | 3,018 | −9.3% |

| 1991 | 2,976 | −1.4% |

| 1996 | 2,775 | −6.8% |

| 2001 | 2,555 | −7.9% |

| 2006 | 2,145 | −16.0% |

| 2011 | 2,047 | −4.6% |

| 2016 | 1,824 | −10.9% |

| 2021 | 1,535 | −15.8% |

| Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics data.[21][22] | ||

Climate edit

Under the Köppen–Geiger classification, Bourke has a hot semi-arid climate (BSh) with a mild amount of rainfall throughout the year. On 4 January 1903, Bourke recorded a maximum temperature of 49.7 °C (121.5 °F), making it tied for the highest temperature recorded anywhere in New South Wales with Menindee, which is located further to the south, and one of the highest maximums ever to be recorded in Australia.[23]

| Climate data for Bourke Airport AWS, New South Wales, Australia (1998–2023 averages and extremes); 107 m AMSL | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 49.7 (121.5) |

47.1 (116.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

38.6 (101.5) |

32.1 (89.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

40.8 (105.4) |

41.6 (106.9) |

46.6 (115.9) |

48.9 (120.0) |

49.7 (121.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 37.6 (99.7) |

35.7 (96.3) |

32.8 (91.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.4 (95.7) |

28.2 (82.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.8 (73.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

13.5 (56.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 32.2 (1.27) |

30.8 (1.21) |

38.9 (1.53) |

23.6 (0.93) |

23.6 (0.93) |

28.6 (1.13) |

14.0 (0.55) |

13.3 (0.52) |

20.2 (0.80) |

28.7 (1.13) |

44.4 (1.75) |

32.9 (1.30) |

331.5 (13.05) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.8 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 58.2 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 24 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 36 | 47 | 41 | 30 | 24 | 22 | 25 | 21 | 29 |

| Source 1: Australian Bureau of Meteorology (1998–present)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_048013_All.shtml | |||||||||||||

Education edit

Bourke has many schools for preschool children, primary and high school students. The Bourke–Walgett School of Distance Education allows children to be schooled at home, from preschool to year 12.

Transportation edit

Bourke can be reached by the Mitchell Highway from both the north from Charleville and Cunnamulla and from the southeast from Nyngan. Brewarrina and Walgett are located on the Kamilaroi Highway that has its western terminus in Bourke. Moree and Goondiwindi, located on the Newell Highway, connect to Bourke via various roads. Cobar via the Kidman Way, is connected from the south.

The town is also served by Bourke Airport and has NSW TrainLink bus service to other regional centres such as Dubbo. It was formerly the largest inland port in the world for exporting wool on the Darling River. The Bourke court house is unique in inland Australia in that it was originally a maritime court and to this day maintains that distinction. That distinction is evident in the crowns that sits above the finials of the flag poles atop the corner parapets of the building.

Prior to its closure, Bourke railway station was the terminus of the Main Western railway line. The railway extension from Byrock opened on 3 September 1885.[25] Passenger services on the line were cancelled in September 1975 with the line closing down entirely in 1986, leaving the station derelict.[26]

Cultural significance edit

Bourke is considered to represent the edge of the settled agricultural districts and the gateway to the outback that lies north and west of Bourke. This is reflected in a traditional east coast Australian expression "back o' Bourke", from the poem by Scottish-Australian poet and bush balladeer Will H. Ogilvie.

The Tourist Information Centre is located on the Mitchell Highway at The Back 'O Bourke Exhibition Centre.[27]

In 1892 a young writer Henry Lawson was sent to Bourke by the Bulletin editor J. F. Archibald to get a taste of outback life and to try to curb his heavy drinking. In Lawson's own words "I got £5 and a railway ticket from the Bulletin and went to Bourke. Painted, picked up in a shearing shed and swagged it for six months". The experience was to have a profound effect on the 25-year-old and his encounter with the harsh realities of bush life inspired much of his subsequent work. Lawson would later write "if you know Bourke you know Australia". In 1992 eight poems, written under a pseudonym and published in the Western Herald, were discovered in the Bourke library archives and confirmed to be Lawson's work.[28]

Bush poets Harry 'Breaker' Morant (1864–1902) and Will H. Ogilvie (1869–1963) also spent time in the Bourke region and based much of their work on the experience.

Eye surgeon Fred Hollows was buried in Bourke after his death in 1993.[29] Fred Hollows had worked at Enngonia and around the Bourke area in the early 1970s and had asked to be buried there.

The Telegraph Hotel, established in 1888 beside the Darling River, has been restored and now operates as the Riverside Motel.[30]

Crime edit

In 2008, persistently high levels of criminal offending in Bourke led to a ban of the takeaway sales of beer in glass bottles, fortified wine larger than 750 mL and cask wine larger than two litres with only 3.5% or less alcohol non-glass bottles being sold midday.[31][32] In 2013, a US-style justice reinvestment program called Maranguka was put in place to combat offending.[33]

By 2017, there had been a 38% reduction in significant juvenile charges in Bourke.[34] However, by 2022 crime in Bourke had again increased which the founder of Maranguka attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic.[34]

In February 2022, ABC Radio's national current affairs program The World Today detailed numerous allegations of local health workers being routinely abused, threatened and attacked by patients at Bourke Hospital.[35] Such incidents led the University of Sydney to suspend student nurse placements in Bourke.[34]

A lead organiser with the New South Wales Nurses and Midwives' Association said the violence against health workers in Bourke was emblematic of the issues facing such staff in remote areas.[34] She claimed administration staff from the front office were being called on to check on patients in the aged care wing because there was an insufficient number of nurses.[34] She believed the patients at the hospital were being neglected due to a lack of staff with just two registered nurses responsible for the emergency department, an acute ward, an aged care wing and a COVID ward during a night shift.[34] She feared a nurse could lose their life through the violence, or that a patient could die through the chronic staffing shortages.[34]

Bourke Shire mayor Barry Hollman expressed concern for the ramifications for the hospital if the ongoing violence prompted health workers to refuse to come to Bourke.[34] He said he was devastated by the level of violence in the town, which had shocked the community.[34]

In a statement, Western New South Wales Local Health District chief executive Mark Spittal said his organisation had a zero tolerance of threatening or criminal behaviour and was working with Bourke Shire Council, various agencies and community leaders to address the issues.[35] Spittal said a number of measures had already been established including a 24/7 security presence and improvements to infrastructure such as lighting with further measures expected to be put in place in the near future.[35]

Media edit

The town is served by four FM and two AM radio stations, and five television channels.

ABC radio broadcasts on both the FM and AM bands and is pivotal to maintaining rural and community ties in the area.

There are three community radio stations based in Bourke. 2WEB broadcasts with 10,000 watts on 585 AM. 2CUZ is the Indigenous radio station on 106.5 FM. Gold FM is the tourist info station on 88.0 FM. The first two stations broadcast to a myriad of communities in the region.

The local paper, The Western Herald, is published on a weekly basis (every Thursday) year-round, except during a short break at Christmas.

Gallery edit

-

Town sign, southern approach from Kidman Way (2021).

-

Levee bank on southern side of town (2021).

-

The Darling River from Bourke Wharf (2010).

-

Oxley Street scene (2021).

-

Poets Corner of Central Park (2021).

-

Oxley Street town centre (2021).

-

Australia Post office (2021).

-

Bourke Bowls Club on a Sunday morning

-

Country Women's Association rest room (2021).

-

M A Davidson Memorial Sports Ground (2021).

-

War memorial (2021).

-

Fire station (2021).

-

Bourke District Hospital, Tarcoon Street (2021).

-

NSW Police Force police station (2021).

-

NSW Police local area command (2021).

-

Anglican church (2021).

-

Bourke Christian Church (2021).

-

Catholic church (2021).

-

Mosque in Bourke cemetery. 19th-century Bourke was home to many Afghan camel keepers

-

Town cemetery, Gorrell Avenue/Kidman Way (2021).

-

Headstones of the old section of the Bourke Cemetery, Gorrell Avenue (2021).

-

Old North Bourke Bridge, opened in 1883 (2014).

-

Lifting span of the old North Bourke Bridge.

-

Old North Bourke bridge, in flood, northern side, North Bourke (2021).

-

Old North Bourke bridge, in flood, southern side, North Bourke (2021).

-

Bourke Cellars, the former Shakespeare Hotel, Mitchell and Glen Streets (2021).

-

Carriers Arms Hotel, then the Cobb and Co. Tavern, Mitchell and Wilson Streets (2021).

-

Central Australian Hotel, Anson Street (2021).

-

Oxford Hotel, Anson Street (2021).

-

Port Bourke Hotel, Mitchell Street (2021).

-

Post Office Hotel (2021).

-

Telegraph Hotel established 1875, now Riverside Motel

-

Cotton fields between Toorale National Park and North Bourke (2021).

See also edit

- List of disasters in Australia by death toll for the 1895–1896 heat wave that killed 47 in Bourke

References edit

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Bourke (Urban Centre/Locality)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ Bourke Shire Aboriginal Heritage Study (PDF) (Report). Dubbo, NSW: OzArk Environmental & Heritage Management. Bourke Shire Council. January 2019. p. 23.

- ^ "Charles Sturt". The Australian Museum. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b Hardy, Bobbie (1969). West of the Darling. Adelaide: Rigby. ISBN 0727003755.

- ^ "SOUTH AUSTRALIA". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XL, no. 666. New South Wales, Australia. 22 April 1859. p. 5. Retrieved 26 February 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Itter, Ian; Bird, Bob (2019). Vincent Dowling. Swan Hill: Ian Itter. ISBN 9780648001621.

- ^ "THE DARLING COUNTRY". Mount Alexander Mail. No. 982. Victoria, Australia. 6 December 1861. p. 3. Retrieved 27 February 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Bourke: 18 Mile Point". Western Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 19 February 1965. p. 13. Retrieved 27 February 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "Fort Bourke Stockade". Western Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 25 May 1951. p. 11. Retrieved 27 February 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Don Fraser for the Engineering Heritage Committee Engineers Australia, Sydney and the Bourke Shire Council (October 2004). "PLAQUING NOMINATION FOR THE 1883 LIFT BRIDGE AT BOURKE N.S.W. AS A NATIONAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK" (PDF).

- ^ "Bourke : About New South Wales". Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "St. Ignatius Roman Catholic Church, Convent & Site". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00603. Retrieved 18 May 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Towers Drug Company Building (former)". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00383. Retrieved 18 May 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Bourke Post Office". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01404. Retrieved 18 May 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Bourke Court House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00791. Retrieved 18 May 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Ardsilla". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00198. Retrieved 18 May 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Old London Bank Building". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00764. Retrieved 18 May 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "North Bourke Bridge, Darling River, 1883 | www.engineersaustralia.org.au". portal.engineersaustralia.org.au. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Statistics by Catalogue Number". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "Search Census data". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "Australia: Climate Extremes" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Australian Government. January 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Bourke Airport AWS, NSW Climate (1998–present)". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "THE RAILWAY TO BOURKE". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 29 August 1885. p. 10. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "'I don't know how we come back from this': Australia's big dry sucks life from once-proud towns". The Guardian. 13 September 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ Bourke station. NSWrail.net, accessed 8 September 2009.

- ^ "background_lawson". robynleeburrows.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "The Fred Hollows Foundation International : Fred in Bourke". hollows.org. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "(Bourke Riverside Motel – Australian Outback Accommodation)". bourkeriversidemotel.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Bourke implements takeaway alcohol ban". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Bourke bans the booze Archived 28 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Land 8 December 2008.

- ^ "Backing Bourke". Four Corners. 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sara, Sally; Williams, Carly; Mitchell, Scott (12 February 2022). "Nurses feared for their lives, as town of Bourke grapples with rising crime". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Sara, Sally (12 February 2022). "Special report: Nurses fearful for their lives". The World Today. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

External links edit

Media related to Bourke, New South Wales at Wikimedia Commons