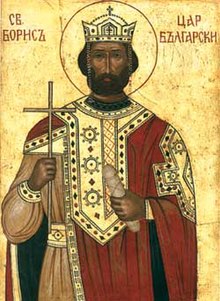

Boris I (also Bogoris), venerated as Saint Boris I (Mihail) the Baptizer (Church Slavonic: Борисъ / Борисъ-Михаилъ, Bulgarian: Борис I / Борис-Михаил; died 2 May 907), was the ruler (knyaz) of the First Bulgarian Empire from 852 to 889. Despite a number of military setbacks, the reign of Boris I was marked with significant events that shaped Bulgarian and European history. With the Christianization of Bulgaria in 864, paganism was abolished. A skillful diplomat, Boris I successfully exploited the conflict between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Papacy to secure an autocephalous Bulgarian Church, thus dealing with the nobility's concerns about Byzantine interference in Bulgaria's internal affairs.

| Boris I | |

|---|---|

| Knyaz of Bulgaria | |

Saint-Knyaz Boris I, Equal-to-the-Apostles | |

| Reign | 852–889 |

| Predecessor | Presian |

| Successor | Vladimir |

| Died | 2 May 907 A monastery near Preslav |

| Spouse | Maria |

| Issue | Vladimir Gavrail Simeon I Evpraksiya Anna |

| House | Krum's dynasty |

| Father | Presian |

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity |

Saint Boris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Equal to the Apostles | |

| Born | 827 |

| Died | 907 |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodoxy |

| Canonized |

|

| Feast | 2 May |

| Patronage | Bulgarian people |

When in 885 the disciples of Saints Cyril and Methodius were banished from Great Moravia, Boris I gave them refuge and provided assistance which saved the Glagolithic and later promoted the development of the Cyrillic script in Preslav and the Slavic literature. After he abdicated in 889, his eldest son and successor tried to restore the old pagan religion but was deposed by Boris I. During the Council of Preslav which followed that event, the Byzantine clergy was replaced with Bulgarian, and the Greek language was replaced with what is now known as Old Church Slavonic.

He is regarded as a saint in the Orthodox Church, as the Prince and baptizer of Bulgaria, and as Equal-to-the-Apostles, with his feast day observed on May 2 and in Synaxis of all venerable and holy Fathers of Bulgaria (movable holiday on the 2nd Sunday of Pentecost).[1][2]

Name and titles

editThe most common theory is that the name Boris is of Bulgar origin.[3][4][5] After his official act of conversion to Christianity, Boris adopted the Christian name Michael. He is sometimes called Boris-Michael in historical research.

The only direct evidence of Boris's title are his seals and the inscription found near the town of Ballsh, modern Albania, and at Varna. There he is called by the Byzantine title "Archon of Bulgaria", which is usually translated as "ruler", and in the 10-11th centuries also as "Knyaz" (Кнѧзъ, Bulg.).[6] In the Bulgarian sources from that period, Boris I is called "Knyaz" and during the Second Bulgarian Empire, "Tsar".[7]

In modern historiography Boris is called by different titles. Most historians accept that he changed his title after his conversion to Christianity. According to them, before the baptism he had the title Khan[8] or Kanasubigi,[9][10] and after that Knyaz.[11]

Reign

editCentral Europe in the 9th century

editThe early 9th century marked the beginning of a fierce rivalry between the Greek East and Latin West, which would ultimately lead to the schism between the Orthodox Church in Constantinople and the Catholic Church in Rome.

As early as 781, the Empress Irene began to seek a closer relationship with the Carolingian dynasty and the Papacy. She negotiated a marriage between her son, Constantine, and Rotrude, a daughter of Charlemagne by his third wife Hildegard. Irene went as far as to send an official to instruct the Frankish princess in Greek; however, Irene herself broke off the engagement in 787, against her son's wishes. When the Second Council of Nicaea of 787 reintroduced the veneration of icons under Empress Irene, the result was not recognized by Charlemagne since no Frankish emissaries had been invited even though Charlemagne was by then ruling more than three provinces of the old Roman empire. While this improved relations with the Papacy, it did not prevent the outbreak of a war with the Franks, who took over Istria and Benevento in 788.

When Charlemagne was proclaimed Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Leo III, the Pope was effectively nullifying the legitimacy of Irene. He certainly desired to increase the influence of the papacy and to honour his protector Charlemagne. Irene, like many of her predecessors since Justinian I, was too weak to protect Rome and its much reduced citizenry and the city was not being ruled by any emperor. Thus, Charlemagne's assumption of the imperial title was not seen as an usurpation in the eyes of the Franks or Italians. It was, however, seen as such in Byzantium, but protests by Irene and her successor Nicephorus I had no great effect.

Mojmír I managed to unite some Slavic princes and established Great Moravia in 833. His successor, Rastislav, also fought against the Germans.[12] Both states tried to maintain good relations with Bulgaria on account of its considerable military power.

Military campaigns

editBoris I was the son and successor of Presian I of Bulgaria. In 852 he sent emissaries to Eastern Francia to confirm the peace treaty of 845.[13][14] At the time of his accession he threatened the Byzantines with an invasion, but his armies did not attack,[15] and he received a small area in Strandzha to the southeast.[16] The peace treaty was not signed, however, although both states exchanged temporary delegations.[17] In 854 the Moravian Prince Rastislav persuaded Boris I to help him against East Francia. According to some sources, some Franks bribed the Bulgarian monarch to attack Louis the German.[18] The Bulgarian-Slav campaign was a disaster, and Louis scored a great victory and invaded Bulgaria.[19] At the same time the Croats waged a war against the Bulgarians. Both peoples had coexisted peacefully up to that time, suggesting that the Croats were paid by Louis to attack Bulgaria and distract Boris' attention from his alliance with Great Moravia.[20] Kanasubigi Boris could not achieve any success, and both sides exchanged gifts and settled for peace.[21] As a result of the military actions in 855, the peace between Bulgaria and Eastern Francia was restored, and Rastislav was forced to fight against Louis alone. In the meantime, a conflict between the Byzantines and Bulgarians had started in 855–856, and Boris, distracted by his conflict with Louis, lost Philippopolis (Plovdiv), the region of Zagora, and the ports around the Gulf of Burgas on the Black Sea to the Byzantine army led by Michael III and the caesar Bardas.[22][23]

Serbia

editAfter the death of Knez Vlastimir of Serbia circa 850, his state was divided between his sons. Vlastimir and Boris' father had fought against each other in the Bulgarian-Serbian War of 839–842, which resulted in a Serbian victory, and Boris sought to avenge that defeat. In 853 or 854, the Bulgarian army led by Vladimir-Rasate, the son of Boris I, invaded Serbia, with the aim of replacing the Byzantine overlordship over the Serbs. The Serbian army was led by Mutimir and his two brothers; they defeated the Bulgarians, capturing Vladimir and 12 boyars.[24] Boris I and Mutimir agreed to peace (and perhaps an alliance[24]), and Mutimir sent his sons Pribislav and Stefan to the border to escort the prisoners, where they exchanged items as a sign of peace. Boris himself gave them "rich gifts", while he was given "two slaves, two falcons, two dogs, and 80 furs".[25][26][27] An internal conflict among the Serbian brothers resulted in Mutimir banishing the two younger brothers to the Bulgarian court.[24][28] Mutimir, however, kept a nephew, Petar, at his court for political reasons.[29] The reason for the feud is not known, though it is postulated that it was a result of treachery.[29] Petar would later defeat Pribislav, Mutimir's son, and take the Serbian throne.

Motivations for baptism and conversion to Christianity

editThere are a number of versions as to why Boris converted to Christianity. Some historians attribute it to the intervention of his sister who had already converted while being at Constantinople.[30] Another story mentions a Greek slave in the ruler's court.[30] A more mythological version is the one in which Boris is astonished and frightened by an icon of Judgement day and thus decides to adopt Christianity.[30] Richard B. Spence sees the decision as deliberate, practical, and politic.[31]

For a variety of diplomatic reasons, Boris became interested in converting to Christianity. In order to both extend his control over the Slavic world and gain an ally against one of the most powerful foes of the Bulgars, the Byzantine Empire, Boris sought to establish an alliance with Louis the German against Ratislav of Moravia.[32] Through this alliance, Louis promised to supply Boris with missionaries, which would have effectively brought the Bulgars under the Roman Church.[33] However, late in 863, the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Michael III declared war on Boris and the Bulgars during a period of famine and natural disasters. Taken by surprise, Boris was forced to make peace with the Byzantines, promising to convert to Christianity according to the eastern rites, in exchange for peace and territorial concessions in Thrace (he regained the region of Zagora recently recovered by the Byzantines).[34] At the beginning of 864, Boris was secretly baptized at Pliska by an embassy of Byzantine clergymen, together with his family and select members of the Bulgarian nobility.[35] With Emperor Michael III as his godfather, Boris also adopted the Christian name Michael.[30]

Separate from diplomatic concerns, Boris was interested in converting himself and the Bulgarians to Christianity to resolve the disunity within the Bulgarian society. When he ascended to the throne, the Bulgars and Slavs were separate elements within Boris' kingdom, the minority Bulgars constituting a military aristocracy. Richard Spence compares it to the relationship between the Normans and Saxons in England.[31] Religious plurality further contributed to divisions within the society. The Slavs had their own polytheistic belief system while the Bulgar elite believed in Tangra, the Sky God, or God of Heaven. The arrival of Methodius and his followers introduced the Cyrillic alphabet, freeing the Bulgarians from dependence on Greek as a written and liturgical language. A Slavic Christian culture developed that helped unify the realm.[31]

Baptism of the Bulgarians and the establishment of the Bulgarian Church

editAfter his baptism, the first major task that Boris undertook was the baptism of his subjects and for this task he appealed to Byzantine priests between 864 and 866.[36] At the same time Boris sought further instruction on how to lead a Christian lifestyle and society and how to set up an autocephalous church from the Byzantine Patriarch Photios. Photios' answer proved less than satisfactory, and Boris sought to gain a more favorable settlement from the Papacy.[37] Boris dispatched emissaries led by the kavhan Peter with a long list of questions to Pope Nicholas I at Rome in August 866, and obtained 106 detailed answers, detailing the essence of religion, law, politics, customs and personal faith. Stemming from his concerns with the baptism of the Bulgarians, Boris also complained to Nicholas about the abuses perpetrated by the Byzantine priests responsible for baptizing the Bulgarians and how he could go about correcting the consequences resulting from these abuses. The pope temporarily glossed over the controversial question of the autocephalous status desired by Boris for his church and sent a large group of missionaries to continue the conversion of Bulgaria in accordance with the western rite.[38][39] Bulgaria's shift towards the Papacy infuriated Patriarch Photios, who wrote an encyclical to the eastern clergy in 867 in which he denounced the practices associated with the western rite and Rome's ecclesiastical intervention in Bulgaria.[39] This occasioned the Photian Schism, which was a major step in the rift between the eastern and western churches.

To deliver his response to Boris’ questions, Pope Nicholas I sent two bishops to Bulgaria: Paul of Populonia and Formosus of Porto. The Pope expected that these priests would execute their episcopal responsibilities to address Boris’ concerns, but did not intend for them to be elevated to the positions that they assumed in the Bulgar hierarchy. In Bulgaria, the activities of Bishop Formosus (later Pope Formosus) met with success, until the pope rejected Boris' request to nominate Formosus as archbishop of Bulgaria. Nicholas justified the rejection of the request by arguing that it was “uncanonical to transfer an already established bishop from one see to another”. The new Pope Adrian II refused Boris' request for a similar nomination of either Formosus or Deacon Marinus (later Pope Marinus I), after which Bulgaria began to shift towards Constantinople once again. At the Fourth Council of Constantinople in 870 the position of the Bulgarian church was reopened by Bulgarian envoys, and the eastern patriarchs adjudicated in favor of Constantinople. This determined the future of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, which was granted the status of an autocephalous archbishopric by the Patriarchate of Constantinople and an archbishop of its own. Later in the 870s, the Patriarch of Constantinople surrendered Bulgaria to the Papacy, but this concession was purely nominal, as it did not affect the actual position of Bulgaria's autocephalous church.[40]

The Christianization of the Bulgarians as a result of Boris’ actions had profound effects not only on the religious belief system of the Bulgarians but also the structure of the Bulgarian government. Upon embracing Christianity, Boris took on the title of Knyaz and joined the community of nations that embraced Christ, to the great delight of the Eastern Roman Empire.[38]

Toward the end of his reign, Boris began to increase the number of native Bulgarian clergy. Consequently, Boris began to send Bulgarians to Constantinople to obtain a monastic education and some of these Bulgarians returned to their homeland to serve as clergymen.[41] In 885, Boris was presented with a new opportunity to establish a native clergy when Slavic-speaking disciples of St. Cyril and St. Methodius were forced to flee from Moravia after a German-inspired reaction to the death of the apostle.[citation needed]

Changes to Bulgarian culture brought on by Clement and Naum

editIn 886 Boris' governor of Belgrade welcomed the disciples of Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, who were exiled from Great Moravia into Bulgaria and sent them on to Boris in Pliska. Boris happily greeted two of these disciples, Clement of Ohrid and Naum of Preslav, who were of noble Bulgarian Slavic origin. To utilize the disciple's talents, Boris commissioned Clement to be a “teacher” in the province of Kutmichevitsa.

Both Clement and Naum were instrumental in furthering the cultural, linguistic and spiritual works of Cyril and Methodius.[42] They set up educational centers in Pliska and in Ohrid to further the development of Slavonic letters and liturgy. Clement later trained thousands of Slavonic-speaking priests who replaced the Greek-speaking clergy from Constantinople still present in Bulgaria. The script that was originally developed by Cyril and Methodius is known as the Glagolitic alphabet.

In Bulgaria, Clement of Ohrid and Naum of Preslav created (or rather compiled) the new Bulgarian script, later called Cyrillic that was declared the official alphabet in 893. Old Bulgarian was declared as the official language in the same year. In the following centuries this script was adopted by other Slavic peoples and states. The introduction of Slavic liturgy paralleled Boris' continued development of churches and monasteries throughout his realm.

Reactions to religious conversion

editConversion to Christianity met great opposition among the Bulgarian elite. Some refused to become Christians while others apostatized after baptism and started a rebellion against Boris for forcing them to be baptized. Some people did not object necessarily to the Christian religion but to the fact that it was brought by foreign priests, which, as a result, established external foreign policy. By breaking the power of the old cults, Boris reduced the influence of the boyars, who resisted the khan's authority.[31] In the summer of 865 a group of Bulgar aristocrats (boyars) started an open revolt.[30] Boris ruthlessly suppressed it and executed 52 boyars together with their entire families.[43] Thus the Christianization continued.

End of Boris' reign

editIn 889 Boris abdicated the throne and became a monk. His son and successor Vladimir attempted a pagan reaction, which brought Boris out of retirement in 893. Vladimir was defeated and Boris had him blinded, his wife shaved and sent to a monastery. Boris gathered the Council of Preslav placing his third son, Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria, on the throne, threatening him with the same fate if he too apostatized. Boris returned to his monastery, emerging once again in c. 895 to help Simeon fight the Magyars, who had invaded Bulgaria in alliance with the Byzantines. After the passing of this crisis, Boris resumed monastic life and died in 907. The location of his retreat, where perhaps he was interred, is not certain; it may be near Preslav, or Pliska, or in a Ravna Monastery near Varna.

Legacy

editSt. Boris Peak on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named for Boris I of Bulgaria.

Boris I's life is featured in the 1985 film "Boris I" (Борис Първи), with Stefan Danailov in the title role.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ (in Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Βόρις – Μιχαὴλ ὁ Ἱσαπόστολος ὁ πρίγκιπας καὶ Φωτιστῆς τοῦ Βουλγαρικοῦ λαοῦ. 2 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ^ "Orthodox Calendar. HOLY TRINITY RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH, a parish of the Patriarchate of Moscow". www.holytrinityorthodox.com. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Проф. Веселин Бешевлиев (Издателство на Отечествения фронт, София 1981)

- ^ Д-р Зоя Барболова - Имена със значение вълк в българската антропонимна система. LiterNet, 30.04.2013, № 4 (161).

- ^ Peter B. Golden, Turks and Khazars: Origins, Institutions, and Interactions in Pre-Mongol Eurasia, Volume 952 of Collected studies, Ashgate/Variorum, 2010, ISBN 1409400034, p. 4.

- ^ Бакалов, Георги. Средновековният български владетел. (Титулатура и инсигнии), София 1995, с. 144, 146, Бобчев, С. С. Княз или цар Борис? (към историята на старобългарското право). Титлите на българските владетели, Българска сбирка, XIV, 5, 1907, с. 311

- ^ Бакалов, Георги. Средновековният български владетел..., с. 144–146

- ^ Златарски, Васил [1927] (1994). „История на Българската държава през Средните векове, т.1, ч.2“, Второ фототипно издание, София: Академично издателство „Марин Дринов“, стр. 29. ISBN 954-430-299-9.

- ^ 12 мита в българската история

- ^ Страница за прабългарите

- ^ Златарски, Васил [1927] (1994). „История на Българската държава през Средните векове, т.1, ч.2“, Второ фототипно издание, София: Академично издателство „Марин Дринов“. ISBN 954-430-299-9.

- ^ К. Грот, Моравия и Мадяры, Петроград, 1881, стр. 108 и сл.

- ^ Rudolfi Fulden. annales, an. 852

- ^ Pertz, Mon. Germ. SS, I, p. 367: legationes Bulgarorum Sclavorumque et absolvit

- ^ Genesios, ed. Bon., p. 85–86

- ^ В. Н. Златарски, Известия за българите, стр. 65–68

- ^ В. Розен, Император Василий Болгаробойца, Петроград, 1883, стр. 14

- ^ Dümmler, каз. съч., I, стр. 38

- ^ Migne, Patrol. gr., t. 126, cap. 34, col. 197

- ^ К. Грот, Известия о сербах и хорватах, стр. 125–127

- ^ Const. Porphyr., De admin, imp., ed. Bon, cap. 31, p. 150–151

- ^ Gjuzelev, p. 130

- ^ Bulgarian historical review, v.33: no. 1–4, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans, p. 141

- ^ F. Raçki, Documenta historiae Chroatie etc., Zagreb, 1877, p. 359.

- ^ П. Шафарик, Славян. древн., II, 1, стр. 289.

- ^ Const. Porphyr., ibid., cap. 32, p. 154-155

- ^ The Serbs, p. 15

- ^ a b Đekić, Đ. 2009, "Why did prince Mutimir keep Petar Gojnikovic?", Teme, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 683–688. PDF

- ^ a b c d e Anderson, 1999, p. 80

- ^ a b c d Spence, Richard B., "Boris I of Bulgaria", Dictionary of World Biography, Vol.2, (Frank Northen Magill, Alison Aves, eds.), Routledge, 1998 ISBN 978- 1579580414

- ^ Sullivan, Richard E. (1994). "Khan Boris and the Conversion of Bulgaria: A case Study of the Impact of Christianity on a Barbarian Society". Christian Missionary Activity in the Early Middle Ages. Variorum: 55–139. ISBN 0-86078-402-9.

- ^ Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. pp. 91–223. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.

- ^ Fine, pp. 118–119

- ^ Anderson, Gerald H. (1999). Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 0-8028-4680-7.

- ^ Antonova, Stamenka E. (2011). "Bulgaria, Patriarchal Orthodox Church of". The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Wiley-Blackwell: 78–93.

- ^ Duffy, Eamon (2006). Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes. Yale University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0-300-11597-0.

- ^ a b Norwich, John Julius (2011). A History of the Papacy. New York: Random House. p. 74.

- ^ a b Duffy, 2006, p. 103

- ^ Simeonova, Liliana (1998). Diplomacy of the Letter and the Cross. Photios, Bulgaria and the Papacy, 860s–880s. A.M. Hakkert, Amsterdam. p. 434. ISBN 90-256-0638-5.

- ^ McGuckin, John Anthony (February 3, 2014). The Concise Encyclopedia of Orthodox Christianity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 68. ISBN 978-1118759332.

- ^ Civita, Michael J. L. (July 2011). "The Orthodox Church of Bulgaria". Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "V. Zlatarski - Istorija 1 B - 3.2".

References

edit- Yordan Andreev, Ivan Lazarov, Plamen Pavlov, Koy koy e v srednovekovna Balgariya, Sofia 1999.

- Bulgarian historical review (2005), United Center for Research and Training in History, Published by Pub. House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, v. 33: no. 1–4.

- Gjuzelev, V., (1988) Medieval Bulgaria, Byzantine Empire, Black Sea, Venice, Genoa (Centre culturel du monde byzantin). Published by Verlag Baier.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Nikolov, A. Making a new basileus: the case of Symeon of Bulgaria (893–927) reconsidered. – In: Rome, Constantinople and Newly converted Europe. Archeological and Historical Evidence. Vol. I. Ed. by M. Salamon, M. Wołoszyn, A. Musin, P. Špehar. Kraków-Leipzig-Rzeszów-Warszawa, 2012, 101–108

- Николов, А., Факти и догадки за събора през 893 година. – В: България в световното културно наследство. Материали от Третата национална конференция по история, археология и културен туризъм "Пътуване към България" - Шумен, 17–19. 05. 2012 г. Съст. Т. Тодоров. Шумен, 2014, 229–237

- Runciman, Steven (1930). "The Two Eagles". A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: George Bell & Sons. OCLC 832687.