Blaise Pascal[a] (19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic writer.

Blaise Pascal | |

|---|---|

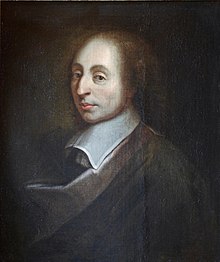

Portrait of Pascal in 1691 | |

| Born | 19 June 1623 Clermont-Ferrand, France |

| Died | 19 August 1662 (aged 39) Paris, France |

| Father | Étienne Pascal |

| Relatives | Marguerite Périer (niece) Jacqueline Pascal (sister) Gilberte Périer (sister) |

Philosophy career | |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

Main interests |

|

Notable ideas | |

| Signature | |

Pascal was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. His earliest mathematical work was on projective geometry; he wrote a significant treatise on the subject of conic sections at the age of 16. He later corresponded with Pierre de Fermat on probability theory, strongly influencing the development of modern economics and social science. In 1642, he started some pioneering work on calculating machines (called Pascal's calculators and later Pascalines), establishing him as one of the first two inventors of the mechanical calculator.[8][9]

Like his contemporary René Descartes, Pascal was also a pioneer in the natural and applied sciences. Pascal wrote in defense of the scientific method and produced several controversial results. He made important contributions to the study of fluids, and clarified the concepts of pressure and vacuum by generalising the work of Evangelista Torricelli. Following Torricelli and Galileo Galilei, in 1647 he rebutted the likes of Aristotle and Descartes who insisted that nature abhors a vacuum.

In 1646, he and his sister Jacqueline identified with the religious movement within Catholicism known by its detractors as Jansenism.[10] Following a religious experience in late 1654, he began writing influential works on philosophy and theology. His two most famous works date from this period: the Lettres provinciales and the Pensées, the former set in the conflict between Jansenists and Jesuits. The latter contains Pascal's wager, known in the original as the Discourse on the Machine,[11][12] a fideistic probabilistic argument for why one should believe in God. In that year, he also wrote an important treatise on the arithmetical triangle. Between 1658 and 1659, he wrote on the cycloid and its use in calculating the volume of solids. Following several years of illness, Pascal died in Paris at the age of 39.

Early life and education

Pascal was born in Clermont-Ferrand, which is in France's Auvergne region, by the Massif Central. He lost his mother, Antoinette Begon, at the age of three.[13] His father, Étienne Pascal, also an amateur mathematician, was a local judge and member of the "Noblesse de Robe". Pascal had two sisters, the younger Jacqueline and the elder Gilberte.

Move to Paris

In 1631, five years after the death of his wife,[2] Étienne Pascal moved with his children to Paris. The newly arrived family soon hired Louise Delfault, a maid who eventually became a key member of the family. Étienne, who never remarried, decided that he alone would educate his children.

The young Pascal showed an extraordinary intellectual ability, with an amazing aptitude for mathematics and science.[14] Etienne had tried to keep his son from learning mathematics; but by the age of 12, Pascal had rediscovered, on his own, using charcoal on a tile floor, Euclid’s first thirty-two geometric propositions, and was thus given a copy of Euclid's Elements.[15]

Essay on Conics

Particularly of interest to Pascal was a work of Desargues on conic sections. Following Desargues' thinking, the 16-year-old Pascal produced, as a means of proof, a short treatise on what was called the Mystic Hexagram, Essai pour les coniques (Essay on Conics) and sent it — his first serious work of mathematics — to Père Mersenne in Paris; it is known still today as Pascal's theorem. It states that if a hexagon is inscribed in a circle (or conic) then the three intersection points of opposite sides lie on a line (called the Pascal line).

Pascal's work was so precocious that René Descartes was convinced that Pascal's father had written it. When assured by Mersenne that it was, indeed, the product of the son and not the father, Descartes dismissed it with a sniff: "I do not find it strange that he has offered demonstrations about conics more appropriate than those of the ancients," adding, "but other matters related to this subject can be proposed that would scarcely occur to a 16-year-old child."[16]

Leaving Paris

In France at that time offices and positions could be—and were—bought and sold. In 1631, Étienne sold his position as second president of the Cour des Aides for 65,665 livres.[17] The money was invested in a government bond which provided, if not a lavish, then certainly a comfortable income which allowed the Pascal family to move to, and enjoy, Paris, but in 1638 Cardinal Richelieu, desperate for money to carry on the Thirty Years' War, defaulted on the government's bonds. Suddenly Étienne Pascal's worth had dropped from nearly 66,000 livres to less than 7,300.[citation needed]

Like so many others, Étienne was eventually forced to flee Paris because of his opposition to the fiscal policies of Richelieu, leaving his three children in the care of his neighbour Madame Sainctot, a great beauty with an infamous past who kept one of the most glittering and intellectual salons in all France. It was only when Jacqueline performed well in a children's play with Richelieu in attendance that Étienne was pardoned. In time, Étienne was back in good graces with the Cardinal and in 1639 had been appointed the king's commissioner of taxes in the city of Rouen—a city whose tax records, thanks to uprisings, were in utter chaos.

Pascaline

In 1642, in an effort to ease his father's endless, exhausting calculations, and recalculations, of taxes owed and paid (into which work the young Pascal had been recruited), Pascal, not yet 19, constructed a mechanical calculator capable of addition and subtraction, called Pascal's calculator or the Pascaline. Of the eight Pascalines known to have survived, four are held by the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris and one more by the Zwinger museum in Dresden, Germany, exhibit two of his original mechanical calculators.[18]

Although these machines are pioneering forerunners to a further 400 years of development of mechanical methods of calculation, and in a sense to the later field of computer engineering, the calculator failed to be a great commercial success. Partly because it was still quite cumbersome to use in practice, but probably primarily because it was extraordinarily expensive, the Pascaline became little more than a toy, and a status symbol, for the very rich both in France and elsewhere in Europe. Pascal continued to make improvements to his design through the next decade, and he refers to some 50 machines that were built to his design.[19] He built 20 finished machines over the following 10 years.[20]

Mathematics

Probability

In 1654, prompted by his friend the Chevalier de Méré, Pascal corresponded with Pierre de Fermat on the subject of gambling problems, and from that collaboration was born the mathematical theory of probability.[21] The specific problem was that of two players who want to finish a game early and, given the current circumstances of the game, want to divide the stakes fairly, based on the chance each has of winning the game from that point. From this discussion, the notion of expected value was introduced. John Ross writes, "Probability theory and the discoveries following it changed the way we regard uncertainty, risk, decision-making, and an individual's and society's ability to influence the course of future events."[22] Pascal, in the Pensées, used a probabilistic argument, Pascal's wager, to justify belief in God and a virtuous life. However, Pascal and Fermat, though doing important early work in probability theory, did not develop the field very far. Christiaan Huygens, learning of the subject from the correspondence of Pascal and Fermat, wrote the first book on the subject. Later figures who continued the development of the theory include Abraham de Moivre and Pierre-Simon Laplace. The work done by Fermat and Pascal into the calculus of probabilities laid important groundwork for Leibniz's formulation of the calculus.[23]

Treatise on the Arithmetical Triangle

Pascal's Traité du triangle arithmétique, written in 1654 but published posthumously in 1665, described a convenient tabular presentation for binomial coefficients which he called the arithmetical triangle, but is now called Pascal's triangle.[24][25] The triangle can also be represented:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 15 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 20 | |||

| 4 | 1 | 5 | 15 | ||||

| 5 | 1 | 6 | |||||

| 6 | 1 |

He defined the numbers in the triangle by recursion: Call the number in the (m + 1)th row and (n + 1)th column tmn. Then tmn = tm–1,n + tm,n–1, for m = 0, 1, 2, ... and n = 0, 1, 2, ... The boundary conditions are tm,−1 = 0, t−1,n = 0 for m = 1, 2, 3, ... and n = 1, 2, 3, ... The generator t00 = 1. Pascal concluded with the proof,

In the same treatise, Pascal gave an explicit statement of the principle of mathematical induction.[24] In 1654, he proved Pascal's identity relating the sums of the p-th powers of the first n positive integers for p = 0, 1, 2, ..., k.[26]

That same year, Pascal had a religious experience, and mostly gave up work in mathematics.

Cycloid

In 1658, Pascal, while suffering from a toothache, began considering several problems concerning the cycloid. His toothache disappeared, and he took this as a heavenly sign to proceed with his research. Eight days later he had completed his essay[27] and, to publicize the results, proposed a contest.[28]

Pascal proposed three questions relating to the center of gravity, area and volume of the cycloid, with the winner or winners to receive prizes of 20 and 40 Spanish doubloons. Pascal, Gilles de Roberval and Pierre de Carcavi were the judges, and neither of the two submissions (by John Wallis and Antoine de Lalouvère) were judged to be adequate.[29] While the contest was ongoing, Christopher Wren sent Pascal a proposal for a proof of the rectification of the cycloid; Roberval claimed promptly that he had known of the proof for years. Wallis published Wren's proof (crediting Wren) in Wallis's Tractus Duo, giving Wren priority for the first published proof.

Physics

Pascal contributed to several fields in physics, most notably the fields of fluid mechanics and pressure. In honour of his scientific contributions, the name Pascal has been given to the SI unit of pressure and Pascal's law (an important principle of hydrostatics). He introduced a primitive form of roulette and the roulette wheel in his search for a perpetual motion machine.[30]

Fluid dynamics

His work in the fields of hydrodynamics and hydrostatics centered on the principles of hydraulic fluids. His inventions include the hydraulic press (using hydraulic pressure to multiply force) and the syringe. He proved that hydrostatic pressure depends not on the weight of the fluid but on the elevation difference. He demonstrated this principle by attaching a thin tube to a barrel full of water and filling the tube with water up to the level of the third floor of a building. This caused the barrel to leak, in what became known as Pascal's barrel experiment.

Vacuum

By 1647, Pascal had learned of Evangelista Torricelli's experimentation with barometers. Having replicated an experiment that involved placing a tube filled with mercury upside down in a bowl of mercury, Pascal questioned what force kept some mercury in the tube and what filled the space above the mercury in the tube. At the time, most scientists including Descartes believed in a plenum, i. e. some invisible matter filled all of space, rather than a vacuum ("Nature abhors a vacuum)." This was based on the Aristotelian notion that everything in motion was a substance, moved by another substance.[31] Furthermore, light passed through the glass tube, suggesting a substance such as aether rather than vacuum filled the space.

Following more experimentation in this vein, in 1647 Pascal produced Experiences nouvelles touchant le vide ("New experiments with the vacuum"), which detailed basic rules describing to what degree various liquids could be supported by air pressure. It also provided reasons why it was indeed a vacuum above the column of liquid in a barometer tube. This work was followed by Récit de la grande expérience de l'équilibre des liqueurs ("Account of the great experiment on equilibrium in liquids") published in 1648.

First atmospheric pressure vs. altitude experiment

The Torricellian vacuum found that air pressure is equal to the weight of 30 inches of mercury. If air has a finite weight, Earth's atmosphere must have a maximum height. Pascal reasoned that if true, air pressure on a high mountain must be less than at a lower altitude. He lived near the Puy de Dôme mountain, 4,790 feet (1,460 m) tall, but his health was poor so could not climb it.[32] On 19 September 1648, after many months of Pascal's friendly but insistent prodding, Florin Périer, husband of Pascal's elder sister Gilberte, was finally able to carry out the fact-finding mission vital to Pascal's theory. The account, written by Périer, reads:

The weather was chancy last Saturday...[but] around five o'clock that morning...the Puy-de-Dôme was visible...so I decided to give it a try. Several important people of the city of Clermont had asked me to let them know when I would make the ascent...I was delighted to have them with me in this great work...

...at eight o'clock we met in the gardens of the Minim Fathers, which has the lowest elevation in town....First I poured 16 pounds of quicksilver...into a vessel...then took several glass tubes...each four feet long and hermetically sealed at one end and opened at the other...then placed them in the vessel [of quicksilver]...I found the quick silver stood at 26" and 3+1⁄2 lines above the quicksilver in the vessel...I repeated the experiment two more times while standing in the same spot...[they] produced the same result each time...

I attached one of the tubes to the vessel and marked the height of the quicksilver and...asked Father Chastin, one of the Minim Brothers...to watch if any changes should occur through the day...Taking the other tube and a portion of the quick silver...I walked to the top of Puy-de-Dôme, about 500 fathoms higher than the monastery, where upon experiment...found that the quicksilver reached a height of only 23" and 2 lines...I repeated the experiment five times with care...each at different points on the summit...found the same height of quicksilver...in each case...[33]

Pascal replicated the experiment in Paris by carrying a barometer up to the top of the bell tower at the church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie, a height of about 50 metres. The mercury dropped two lines. He found with both experiments that an ascent of 7 fathoms lowers the mercury by half a line.[note 1] Note: Pascal used pouce and ligne for "inch" and "line", and toise for "fathom".[34]

In a reply to Étienne Noël, who believed in the plenum, Pascal wrote, echoing contemporary notions of science and falsifiability: "In order to show that a hypothesis is evident, it does not suffice that all the phenomena follow from it; instead, if it leads to something contrary to a single one of the phenomena, that suffices to establish its falsity."[35]

Blaise Pascal Chairs are given to outstanding international scientists to conduct their research in the Ile de France region.[36]

Adult life: religion, literature, and philosophy

Religious conversion

In the winter of 1646, Pascal's 58-year-old father broke his hip when he slipped and fell on an icy street of Rouen; given the man's age and the state of medicine in the 17th century, a broken hip could be a very serious condition, perhaps even fatal. Rouen was home to two of the finest doctors in France, Deslandes and de la Bouteillerie. The elder Pascal "would not let anyone other than these men attend him...It was a good choice, for the old man survived and was able to walk again..."[37] However treatment and rehabilitation took three months, during which time La Bouteillerie and Deslandes had become regular visitors.

Both men were followers of Jean Guillebert, proponent of a splinter group from Catholic teaching known as Jansenism. This still fairly small sect was making surprising inroads into the French Catholic community at that time. It espoused rigorous Augustinism. Blaise spoke with the doctors frequently, and after their successful treatment of his father, borrowed from them works by Jansenist authors. In this period, Pascal experienced a sort of "first conversion" and began to write on theological subjects in the course of the following year.

Pascal fell away from this initial religious engagement and experienced a few years of what some biographers have called his "worldly period" (1648–54). His father died in 1651 and left his inheritance to Pascal and his sister Jacqueline, for whom Pascal acted as conservator. Jacqueline announced that she would soon become a postulant in the Jansenist convent of Port-Royal. Pascal was deeply affected and very sad, not because of her choice, but because of his chronic poor health; he needed her just as she had needed him.

Suddenly there was war in the Pascal household. Blaise pleaded with Jacqueline not to leave, but she was adamant. He commanded her to stay, but that didn't work, either. At the heart of this was...Blaise's fear of abandonment...if Jacqueline entered Port-Royal, she would have to leave her inheritance behind...[but] nothing would change her mind.[38]

By the end of October in 1651, a truce had been reached between brother and sister. In return for a healthy annual stipend, Jacqueline signed over her part of the inheritance to her brother. Gilberte had already been given her inheritance in the form of a dowry. In early January, Jacqueline left for Port-Royal. On that day, according to Gilberte concerning her brother, "He retired very sadly to his rooms without seeing Jacqueline, who was waiting in the little parlor..."[39] In early June 1653, after what must have seemed like endless badgering from Jacqueline, Pascal formally signed over the whole of his sister's inheritance to Port-Royal, which, to him, "had begun to smell like a cult."[40] With two-thirds of his father's estate now gone, the 29-year-old Pascal was now consigned to genteel poverty.

For a while, Pascal pursued the life of a bachelor. During visits to his sister at Port-Royal in 1654, he displayed contempt for affairs of the world but was not drawn to God.[41]

Memorial

On the 23 of November, 1654, between 10:30 and 12:30 at night, Pascal had an intense religious experience and immediately wrote a brief note to himself which began: "Fire. God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of the philosophers and the scholars..." and concluded by quoting Psalm 119:16: "I will not forget thy word. Amen." He seems to have carefully sewn this document into his coat and always transferred it when he changed clothes; a servant discovered it only by chance after his death.[42] This piece is now known as the Memorial. The story of a carriage accident as having led to the experience described in the Memorial is disputed by some scholars.[43] His belief and religious commitment revitalized, Pascal visited the older of two convents at Port-Royal for a two-week retreat in January 1655. For the next four years, he regularly travelled between Port-Royal and Paris. It was at this point immediately after his conversion when he began writing his first major literary work on religion, the Provincial Letters.

Literature

In literature, Pascal is regarded as one of the most important authors of the French Classical Period and is read today as one of the greatest masters of French prose. His use of satire and wit influenced later polemicists.

The Provincial Letters

Beginning in 1656–57, Pascal published his memorable attack on casuistry, a popular ethical method used by Catholic thinkers in the early modern period (especially the Jesuits, and in particular Antonio Escobar). Pascal denounced casuistry as the mere use of complex reasoning to justify moral laxity and all sorts of sins. The 18-letter series was published between 1656 and 1657 under the pseudonym Louis de Montalte and incensed Louis XIV. The king ordered that the book be shredded and burnt in 1660. In 1661, in the midst of the formulary controversy, the Jansenist school at Port-Royal was condemned and closed down; those involved with the school had to sign a 1656 papal bull condemning the teachings of Jansen as heretical. The final letter from Pascal, in 1657, had defied Alexander VII himself. Even Pope Alexander, while publicly opposing them, nonetheless was persuaded by Pascal's arguments.

Aside from their religious influence, the Provincial Letters were popular as a literary work. Pascal's use of humor, mockery, and vicious satire in his arguments made the letters ripe for public consumption, and influenced the prose of later French writers like Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

It is in the Provincial Letters that Pascal made his oft-quoted apology for writing a long letter, as he had not had time to write a shorter one. From Letter XVI, as translated by Thomas M'Crie: 'Reverend fathers, my letters were not wont either to be so prolix, or to follow so closely on one another. Want of time must plead my excuse for both of these faults. The present letter is a very long one, simply because I had no leisure to make it shorter.'

Charles Perrault wrote of the Letters: "Everything is there—purity of language, nobility of thought, solidity in reasoning, finesse in raillery, and throughout an agrément not to be found anywhere else."[44]

Philosophy

Pascal is arguably best known as a philosopher, considered by some the second greatest French mind behind René Descartes. He was a dualist following Descartes.[45] However, he is also remembered for his opposition to both the rationalism of the likes of Descartes and simultaneous opposition to the main countervailing epistemology, empiricism, preferring fideism.

In terms of God, Descartes and Pascal disagreed. Pascal wrote that "I cannot forgive Descartes. In all his philosophy he would have been quite willing to dispense with God, but he couldn't avoid letting him put the world in motion; afterwards he didn't need God anymore".[46] He opposed the rationalism of people like Descartes as applied to the existence of a God, preferring faith as "reason can decide nothing here".[47] For Pascal the nature of God was such that such proofs cannot reveal God. Humans "are in darkness and estranged from God" because "he has hidden Himself from their knowledge".[48]

He cared above all about the philosophy of religion. Pascalian theology has grown out of his perspective that humans are, according to Wood, "born into a duplicitous world that shapes us into duplicitous subjects and so we find it easy to reject God continually and deceive ourselves about our own sinfulness".[49]

Philosophy of mathematics

Pascal's major contribution to the philosophy of mathematics came with his De l'Esprit géométrique ("Of the Geometrical Spirit"), originally written as a preface to a geometry textbook for one of the famous Petites écoles de Port-Royal ("Little Schools of Port-Royal"). The work was unpublished until over a century after his death. Here, Pascal looked into the issue of discovering truths, arguing that the ideal of such a method would be to found all propositions on already established truths. At the same time, however, he claimed this was impossible because such established truths would require other truths to back them up—first principles, therefore, cannot be reached. Based on this, Pascal argued that the procedure used in geometry was as perfect as possible, with certain principles assumed and other propositions developed from them. Nevertheless, there was no way to know the assumed principles to be true.

Pascal also used De l'Esprit géométrique to develop a theory of definition. He distinguished between definitions which are conventional labels defined by the writer and definitions which are within the language and understood by everyone because they naturally designate their referent. The second type would be characteristic of the philosophy of essentialism. Pascal claimed that only definitions of the first type were important to science and mathematics, arguing that those fields should adopt the philosophy of formalism as formulated by Descartes.

In De l'Art de persuader ("On the Art of Persuasion"), Pascal looked deeper into geometry's axiomatic method, specifically the question of how people come to be convinced of the axioms upon which later conclusions are based. Pascal agreed with Montaigne that achieving certainty in these axioms and conclusions through human methods is impossible. He asserted that these principles can be grasped only through intuition, and that this fact underscored the necessity for submission to God in searching out truths.

Pensées

Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed.

— Blaise Pascal, Pensées, No. 200

Pascal's most influential theological work, referred to posthumously as the Pensées ("Thoughts") is widely considered to be a masterpiece, and a landmark in French prose. When commenting on one particular section (Thought #72), Sainte-Beuve praised it as the finest pages in the French language.[50] Will Durant hailed the Pensées as "the most eloquent book in French prose".[51]

The Pensées was not completed before his death. It was to have been a sustained and coherent examination and defense of the Christian faith, with the original title Apologie de la religion Chrétienne ("Defense of the Christian Religion"). The first version of the numerous scraps of paper found after his death appeared in print as a book in 1669 titled Pensées de M. Pascal sur la religion, et sur quelques autres sujets ("Thoughts of M. Pascal on religion, and on some other subjects") and soon thereafter became a classic.

One of the Apologie's main strategies was to use the contradictory philosophies of Pyrrhonism and Stoicism, personalized by Montaigne on one hand, and Epictetus on the other, in order to bring the unbeliever to such despair and confusion that he would embrace God.

Last works and death

T. S. Eliot described him during this phase of his life as "a man of the world among ascetics, and an ascetic among men of the world." Pascal's ascetic lifestyle derived from a belief that it was natural and necessary for a person to suffer. In 1659, Pascal fell seriously ill. During his last years, he frequently tried to reject the ministrations of his doctors, saying, "Don't pity me, sickness is the natural state of Christians, because in it we are, as we should always be, in the suffering of evils, in the deprivation of all the goods and pleasures of the senses, free from all the passions that work throughout the course of life, without ambition, without avarice, in the continual expectation of death."[52][53] Desiring to imitate Jesus’ poverty of spirit, in his spirit of zeal and charity, Pascal said if God allowed him to recover from his illness, he would be resolved to "have no other employment or occupation for the rest of my life than the service of the poor."[54]

Louis XIV suppressed the Jansenist movement at Port-Royal in 1661. In response, Pascal wrote one of his final works, Écrit sur la signature du formulaire ("Writ on the Signing of the Form"), exhorting the Jansenists not to give in. Later that year, his sister Jacqueline died, which convinced Pascal to cease his polemics on Jansenism. Pascal's last major achievement, returning to his mechanical genius, was inaugurating perhaps the first bus line, the carrosses à cinq sols, moving passengers within Paris in a carriage with many seats. Pascal also designated the operation principles which were later used to plan public transportation: The carriages had a fixed route, fixed price, and left even if there were no passengers.[55] It is widely considered that the idea of public transportation was well ahead of time. The lines were not commercially successful, and the last one closed by 1675.[56]

In 1662, Pascal's illness became more violent, and his emotional condition had severely worsened since his sister's death. Aware that his health was fading quickly, he sought a move to the hospital for incurable diseases, but his doctors declared that he was too unstable to be carried. In Paris on 18 August 1662, Pascal went into convulsions and received extreme unction. He died the next morning, his last words being "May God never abandon me," and was buried in the cemetery of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont.[52]

An autopsy performed after his death revealed grave problems with his stomach and other organs of his abdomen, along with damage to his brain. Despite the autopsy, the cause of his poor health was never precisely determined, though speculation focuses on tuberculosis, stomach cancer, or a combination of the two.[57] The headaches which affected Pascal are generally attributed to his brain lesion.[58]

Legacy

One of the Universities of Clermont-Ferrand, France – Université Blaise Pascal – is named after him. Établissement scolaire français Blaise-Pascal in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo is named after Pascal.

The 1969 Eric Rohmer film My Night at Maud's is based on the work of Pascal. Roberto Rossellini directed a filmed biopic, Blaise Pascal, which originally aired on Italian television in 1971.[59] Pascal was a subject of the first edition of the 1984 BBC Two documentary, Sea of Faith, presented by Don Cupitt. The chameleon in the film Tangled is named for Pascal.

A programming language is named for Pascal. In 2014, Nvidia announced its new Pascal microarchitecture, which is named for Pascal. The first graphics cards featuring Pascal were released in 2016.

The 2017 game Nier: Automata has multiple characters named after famous philosophers; one of these is a sentient pacifistic machine named Pascal, who serves as a major supporting character. Pascal creates a village for machines to live peacefully with the androids they are at war with and acts as a parental figure for other machines trying to adapt to their newly-found individuality.

The otter in the Animal Crossing series is named for Pascal.[60]

Minor planet 4500 Pascal is named in his honor.

Pope Paul VI, in encyclical Populorum progressio, issued in 1967, quotes Pascal's Pensées:

True humanism points the way toward God and acknowledges the task to which we are called, the task which offers us the real meaning of human life. Man is not the ultimate measure of man. Man becomes truly man only by passing beyond himself. In the words of Pascal: "Man infinitely surpasses man.[61]

In 2023, Pope Francis released an apostolic letter, Sublimitas et miseria hominis, dedicated to Blaise Pascal, in commemoration of the fourth centenary of his birth.

Works

- "Essai pour les coniques" [Essay on conics] (1639)

- Experiences nouvelles touchant le vide [New experiments with the vacuum] (1647)

- Récit de la grande expérience de l'équilibre des liqueurs [Account of the great experiment on equilibrium in liquids] (1648)

- Traité du triangle arithmétique [Treatise on the arithmetical triangle] (written c. 1654;[62] publ. 1665)

- Lettres provinciales [The provincial letters] (1656–57)

- De l'Esprit géométrique [On the geometrical spirit] (1657 or 1658)

- Écrit sur la signature du formulaire (1661)

- Pensées [Thoughts] (incomplete at death; publ. 1670)

- "Discourse on the Passion of Love"

- "On the Conversion of the Sinner"

Notes

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Vincent Jullien (ed.), Seventeenth-Century Indivisibles Revisited, Birkhäuser, 2015, p. 188.

- ^ a b O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (August 2006). "Étienne Pascal". University of St. Andrews, Scotland. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Pascal" Archived 6 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Pascal, Blaise". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Pascal". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Pascal". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ See Schickard versus Pascal: An Empty Debate? Archived 8 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine and Marguin, Jean (1994). Histoire des instruments et machines à calculer, trois siècles de mécanique pensante 1642–1942 (in French). Hermann. p. 48. ISBN 978-2-7056-6166-3.

- ^ d'Ocagne, Maurice (1893). Le calcul simplifié (in French). Gauthier-Villars et fils. p. 245. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ "Blaise Pascal". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ Grumball, Kevin Shaun. "Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy" (PDF). University of Nottingham. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Devlin, p. 20.

- ^ "Blaise Pascal | Biography, Facts, & Inventions | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 8 April 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Cole, J. R. (1995). Pascal : the man and his two loves. United Kingdom: NYU Press. p. 40

- ^ The Story of Civilization: Volume 8, "The Age of Louis XIV" by Will & Ariel Durant; chapter II, subsection 4.1 p.56)

- ^ Connor, James A., Pascal's wager: the man who played dice with God (HarperCollins, NY, 2006) ISBN 0-06-076691-3 p. 42

- ^ A complete list of known Pascalines and also a review of contemporary replicas can be found at Surviving Pascalines Archived 5 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine and Replica Pascalines Archived 5 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine at http://things-that-count.net Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (fr) La Machine d'arithmétique, Blaise Pascal Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Wikisource

- ^ Mourlevat, Guy (1988). Les machines arithmétiques de Blaise Pascal (in French). Clermont-Ferrand: La Française d'Edition et d'Imprimerie. p. 12.

- ^ Devlin, p. 24.

- ^ Ross, John F. (2004). "Pascal's legacy". EMBO Reports. 5 (Suppl 1): S7–S10. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400229. PMC 1299210. PMID 15459727.

- ^ "The Mathematical Leibniz". Math.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ a b Katz, Victor (2009). "14.3: Elementary Probability". A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Addison-Wesley. p. 491. ISBN 978-0-321-38700-4.

- ^ Pascal's triangle | World of Mathematics Summary. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Kieren MacMillan, Jonathan Sondow (2011). "Proofs of power sum and binomial coefficient congruences via Pascal's identity". American Mathematical Monthly. 118 (6): 549–551. arXiv:1011.0076. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.118.06.549. S2CID 207521003.

- ^ Ball, W. W. Rouse (16 September 2010). A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (PDF). New York, NY, USA: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 234. ISBN 978-0486206301.

- ^ Ferroli, D. (April 1935). "A Note on Blaise Pascal (1623-1662). A Forerunner of Leibnitz and Newton in the Discovery of the Calculus". Current Science. 3 (10): 459–461. JSTOR 24221628. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Conner, James A. (2006), Pascal's Wager: The Man Who Played Dice with God (1st ed.), HarperCollins, pp. 224, ISBN 9780060766917

- ^ MIT, "Inventor of the Week Archive: Pascal : Mechanical Calculator", May 2003. "Pascal worked on many versions of the devices, leading to his attempt to create a perpetual motion machine. He has been credited with introducing the roulette machine, which was a by-product of these experiments."

- ^ Aristotle, Physics, VII, 1.

- ^ Ley, Willy (June 1966). "The Re-Designed Solar System". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- ^ Périer to Pascal, 22 September 1648, Pascal, Blaise. Oeuvres complètes. (Paris: Seuil, 1960), 2:682.

- ^ Rougier, Louis (1 October 2010). "– Chapitre XI – La Grande expérience de l'équilibre des liqueurs". Philosophia Scientiæ. Travaux d'histoire et de philosophie des sciences (in French) (14–2): 196–206. doi:10.4000/philosophiascientiae.189. ISSN 1281-2463. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Pour faire qu'une hypothèse soit évidente, il ne suffit pas que tous les phénomènes s'en ensuivent, au lieu que, s'il s'ensuit quelque chose de contraire à un seul des phénomènes, cela suffit pour assurer de sa fausseté, in Les Lettres de Blaise Pascal: Accompagnées de Lettres de ses Correspondants Publiées, ed. Maurice Beaufreton, 6th edition (Paris: G. Crès, 1922), 25–26, available at http://gallica.bnf.fr Archived 18 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine and translated in Saul Fisher, Pierre Gassendi's Philosophy and Science: Atomism for Empiricists Brill's Studies in Intellectual History 131 (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005), 126 n.7

- ^ "Chaires Blaise Pascal". Chaires Blaise Pascal. Archived from the original on 13 June 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ Connor, James A., Pascal's wager: the man who played dice with God (HarperCollins, NY, 2006) ISBN 0-06-076691-3 p. 70

- ^ Miel, Jan. Pascal and Theology. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969), p. 122

- ^ Jacqueline Pascal, "Memoir" p. 87

- ^ Miel, Jan. Pascal and Theology. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969), p. 124

- ^ Richard H. Popkin, Paul Edwards (ed.), Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1967 edition, s.v. "Pascal, Blaise.", vol. 6, p. 52–55, New York: Macmillan

- ^ Pascal, Blaise. Oeuvres complètes. (Paris: Seuil, 1960), p. 618

- ^ MathPages, Hold Your Horses. Archived 29 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine For the sources on which the hypothesis of a link between a carriage accident and Pascal's second conversion is based, and for a sage weighing of the evidence for and against, see Henri Gouhier, Blaise Pascal: Commentaires, Vrin, 1984, pp. 379ff.

- ^ Charles Perrault, Parallèle des Anciens et des Modernes (Paris, 1693), Vol. I, p. 296.

- ^ Ariew, Roger (2007). Descartes and Pascal. Perspectives on Science 15 (4):397-409.

- ^ Bergmans, Luc; Koetsier, T., eds. (2004). Mathematics and the Divine A Historical Study. Elsevier. p. 402.

- ^ Shand, John, ed. (2004). Fundamentals of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. p. 391.

- ^ A Companion to Phenomenology and Existentialism. Wiley. 2009. p. 140.

- ^ Blaise Pascal on Duplicity, Sin, and the Fall. Changing Paradigms in Historical and Systematic Theology. Oxford University Press. 4 July 2013. ISBN 9780199656363. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Sainte-Beuve, Seventeenth Century ISBN 1-113-16675-4 p. 174 (2009 reprint).

- ^ The Story of Civilization: Volume 8, "The Age of Louis XIV" by Will & Ariel Durant, chapter II, Subsection 4.4, p. 66 ISBN 1-56731-019-2

- ^ a b Muir, Jane. Of Men and Numbers Archived 11 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. (New York: Dover Publications, Inc, 1996). ISBN 0-486-28973-7, p. 104.

- ^ Périer, Gilberte (1845). "Lettres, opuscules et mémoires de madame Périer et de Jacqueline, sœurs de Pascal, et de Marguerite Périer, sa nièce". BnF Galica. pp. 41–42.

- ^ Périer, Gilberte (1845). "Lettres, opuscules et mémoires de madame Périer et de Jacqueline, sœurs de Pascal, et de Marguerite Périer, sa nièce". BnF Galica. p. 44.

- ^ Blinkin, Mikhail (20 August 2021). "Это в моде: почему в мире возрождается общественный транспорт". Post-Nauka (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Alfred, Randy (17 March 2008). "March 18, 1662: The Bus Starts Here ... in Paris". Wired. Archived from the original on 14 October 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Muir, Jane. Of Men and Numbers Archived 11 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. (New York: Dover Publications, Inc, 1996). ISBN 0-486-28973-7, p. 103.

- ^ Zanello, Marc; Arnaud, Eric; Di Rocco, Federico (1 April 2015). "The mysteries of Blaise Pascal's sutures". Child's Nervous System. 31 (4): 503–506. doi:10.1007/s00381-015-2622-9. ISSN 1433-0350.

- ^ Blaise Pascal at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ "Animal Crossing: New Horizons: Pascal - Spawn Times, Locations And Mermaid Clothing Rewards". 8 November 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Populorum Progressio (March 26, 1967) | Paul VI". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ "David Pengelley - "Pascal's Treatise on the Arithmetical Triangle"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ 1 ligne = 2.256 mm, and 1 toise = 1.949 m. Mercury density is 13.534 g/cm3. So by Pascal's numbers, the density of air is about 1.1 kg/m^3.

Further reading

- Adamson, Donald. Blaise Pascal: Mathematician, Physicist, and Thinker about God (1995) ISBN 0-333-55036-6

- Adamson, Donald. "Pascal's Views on Mathematics and the Divine," Archived 7 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine Mathematics and the Divine: A Historical Study (eds. T. Koetsier and L. Bergmans. Amsterdam: Elsevier 2005), pp. 407–21.

- Broome, J.H. Pascal. London: E. Arnold, 1965. ISBN 0-7131-5021-1

- Compagnon, Antoine. A Summer with Pascal. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2024.

- Campe, Rüdiger, "Numbers and Calculation in Context: The Game of Decision - Pascal" in The Game of Probability. Literature and Calculation from Pascal and Kleist, Stanford University Press, 2012

- Davidson, Hugh M. Blaise Pascal. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1983.

- Devlin, Keith (2008). The Unfinished Game: Pascal, Fermat, and the Seventeenth-Century Letter that Made the World Modern. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00910-7.

- Farrell, John. "Pascal and Power". Chapter seven of Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau (Cornell UP, 2006).

- Goldmann, Lucien, The hidden God; a study of tragic vision in the Pensees of Pascal and the tragedies of Racine (original ed. 1955, Trans. Philip Thody. London: Routledge, 1964).

- Groothuis, Douglas. On Pascal. (Belmont: Wadsworth, 2002). ISBN 978-0534583910

- Jordan, Jeff. Pascal's Wager: Pragmatic Arguments and Belief in God. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006.

- Landkildehus, Søren. "Kierkegaard and Pascal as kindred spirits in the Fight against Christendom" in Kierkegaard and the Renaissance and Modern Traditions (ed. Jon Stewart. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2009).

- Mackie, John Leslie. The Miracle of Theism: Arguments for and against the Existence of God. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982).

- Stafford Harry Northcote, Viscount Saint Cyres, Pascal (London: Smith, Elder & Company, 1909; New York: E. P. Dutton)

- Pugh, Anthony R. The Composition of Pascal's Apologia, (University of Toronto Press, 1984).

- Saintsbury, George; Chrystal, George (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 878–881.

- Saka, Paul (2001). "Pascal's Wager and the Many Gods Objection". Religious Studies. 37 (3): 321–41. doi:10.1017/S0034412501005686. S2CID 170266714.

- Stephen, Leslie. . Studies of a Biographer. Vol. 2. London: Duckworth and Co. pp. 241–284.

- Tobin, Paul. "The Rejection of Pascal's Wager: A Skeptic's Guide to the Bible and the Historical Jesus". authorsonline.co.uk, 2009.

- Yves Morvan, Pascal à Mirefleurs ? Les dessins de la maison de Domat, Impr. Blandin, 1985. (FRBNF40378895)

External links

- Oeuvres complètes, volume 2 (1858) Paris: Libraire de L Hachette et Cie, link from HathiTrust.

- Works by Blaise Pascal at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Blaise Pascal at the Internet Archive

- Works by Blaise Pascal at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Correspondence of Blaise Pascal in EMLO

- Simpson, David. ""Blaise Pascal"". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Clarke, Desmond. "Blaise Pascal". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Blaise Pascal at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Pensées de Blaise Pascal. Renouard, Paris 1812 (2 vols.) (Digitized)

- Discussion of the Pascaline, its history, mechanism, surviving examples, and modern replicas at http://things-that-count.net

- Pascal's Memorial in orig. French/Latin and modern English, trans. Elizabeth T. Knuth.

- Biography, Bibliography. (in French)

- Works by Blaise Pascal at Open Library

- BBC Radio 4. In Our Time: Pascal.

- Blaise Pascal featured on the 500 French Franc banknote in 1977. Archived 16 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Blaise Pascal's works: text, concordances and frequency lists

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- Etext of Pascal's Pensées (English, in various formats)

- Etext of Pascal's Lettres Provinciales (English)

- Etext of a number of Pascal's minor works (English translation) including, De l'Esprit géométrique and De l'Art de persuader.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Blaise Pascal", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews